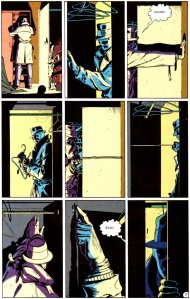

I read the first issue of Watchmen while it was still on comic shop shelves back in 1986. Though “read” is the wrong word. A total of three words appear on pages five, six, seven, and eight. No captions. No thought bubbles. No dialogue. Just Rorschach mumbling “Hunh,” “Ehh,” and, my favorite, “Hurm” to himself as he investigates a crime scene. The action is cerebral. No heroes and villains exchanging punches and power blasts. Rorschach notices that the murder victim’s closet is oddly shallow, and then bends a coat hanger to measure it against the depth of the adjacent wall. A further search reveals a secret button, and then a hidden compartment, complete with (SPOILER ALERT!) the Comedian’s superhero costume.

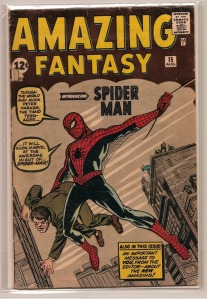

That’s just nine panels of Gibson and Moore’s unnarrated 31-panel sequence. I’d never “read” anything like it. Not that Moore had anything against the English language. Look at the pages right before and after the silent sequence. 198 and 199 words each. When chatting, the Watchmen are as wordy as Spider-Man in his 1962 debut. Open Amazing Fantasy #15 and the first two pages clock in at 196 and 234 words each.

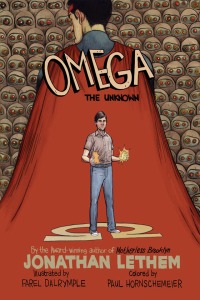

Not many letters shook loose in the leap from Silver to Bronze Age. Take a couple of pages from my personal ur-comic, The Defenders #15 of 1974, and you get 232 and 169. When Omega the Unknown debuted two years later, wordage had shrunk only a little, with pages of 156 and (I hope you realize how annoying it is to count these) 177.

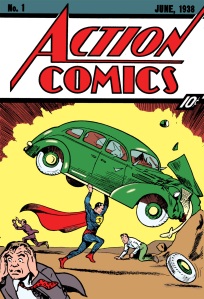

But now fly back to the Golden Age. Scan Action Comics #1, and the 1938 Superman only muscles out 94 and 95 words. The mean skyrockets if you average in Jerry Siegel’s two-page prose story in the back Superman #1, but DC was only placating some now obscure publishing requirement. Marvel included a similar experiment in 1975, dropping single pages of prose into Defenders episodes (the improbably advanced vocabulary included “vacuous,” “belie,” and “veritable.”) My nine-year-old eyes barely skimmed them.

Despite varying word counts, the maximum for a dialogue-heavy panel remains about the same through the decades. Clark and his Daily Star boss cram in 30 words. Same number as the more talkative Omega panels. Peter Parker’s would-be manager leans over him with a 38-word speech bubble. And the cops investigating the Comedian’s death spit out some 35 words per panel too. So dialogue is the comic book’s universal constant. Moore didn’t mess with that. When talking, his characters sound like everybody else. The difference is when they shut up.

Before the mid-eighties, comic books were written in an omniscient third person voice. Those pages of prose in 1975 weren’t a freakish contradiction. They were the culmination of the industry’s style, the medium’s secret default setting. The background hum of talk. The author just couldn’t keep his mouth closed. It was as if he didn’t trust all those vacuous little pictures not to belie his veritable story.

“It takes a very sophisticated writer of long experience and dedication,” Will Eisner explains, “to accept the total castration of his words, as, for example, a series of exquisitely written balloons that are discarded in favor of an equally exquisite pantomime.”

There was a lot of castration anxiety from early comic book writers. Jerry Siegel’s Superman captions read like instructions to artist Joe Shuster: “With a sharp snap the blade breaks upon Superman’s tough skin!” Bill Finger’s Batman captions distrust Bob Kane’s pen even more: “The ‘Bat-Man’ lashes out with a terrific right . . . He grabs his second adversary in a deadly headlock . . . and with a might heave . . . sends the burly criminal flying through space.”

Two decades later and Spider-Man was just as redundant: “Wrapped in his own thoughts, Peter doesn’t hear the auto which narrowly misses him, until the last instant! And then, unnoticed by the riders, he unthinkingly leaps to safety—but what a leap it is!” Steve Ditko and Stan Lee tell the core of the origin—the radioactive spider bite—in three panels, speechless but for Peter’s “Ow!” But those three captions cram in 112 words.

Lee understood the complexity of visual story-telling. (The original Amazing Fantasy art boards include his margin note: “Steve—make this a closed sedan. No arms showing. Don’t imply wreckless driving—S.”) But comic book convention mandated narration, regardless of redundancy. Even when working without a script, Ditko covered his pages in empty captions and talk bubbles for Lee to fill in later. In Amazing Spider-Man #1, Spider-Man webs a rocket capsule as it flies past the plane he’s balancing on. The panels are visually self-explanatory, but words were still required. Instead of narrated captions, it’s Spider-Man pointlessly announcing “I hit it!” and “Mustn’t let go!” and “I reached it! But now . . .”

Alan Moore trusted pictures. When captions appear in Watchmen, they contain character speech, usually juxtaposed from a previous panel. When characters stop talking, the frame is silent. Nobody is chattering in a box overhead. The murder victim in the first issue isn’t the Comedian. It’s the narrator.

Unlike most deaths in comic books, this one was permanent. When Jonathan Lethem and Karl Rusnak created a new Omega the Unknown in 2008, they opened with two pages of wordless panels. Although Rusnak says Steve Gerber, the original writer, “raised the since out-of-favor device of caption narration to an art form,” Lethem still “wasn’t interested in captioning—in fact I wanted to mostly work without it.”

That goes for most creators today. Look at Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely’s All-Star Superman. Look at Brian Michael Bendis and Mark Bagley’s Ultimate Spider-Man. Look at Robert Kirkman and Tony Moore’s The Walking Dead. It’s not just the word counts that changed. Words count differently.

” The mean skyrockets if you average in Jerry Siegel’s two-page prose story in the back Superman #1, but DC was only placating some now obscure publishing requirement.”

It was actually a Post Office regulation. To qualify for special low periodical mailing rates, magazines needed a minimum number (generally set as two) of pages of prose.

This had some positive outcomes; for example, the war comic Two-Fisted Tales ran informative history mini-essays. And letters from the readers being a particularly cheap way to fill space, thus arguably was born modern comics fandom when editor Julius Schwartz started running letter-writers’addresses in his DC mags.

That 35-words-per-panel limit was actually laid down as dogma by editor Denny O’Neil, and probably holds throughout the commercial comics industry.

As an intern at Marvel, I was always frustrated by the addition of captioning over beautifully composed, silent pages. They tempered the gravitas. My perspective is slowly swinging back the other way… the captions reveal a kind of desperation, or earnestness that’s quickly becoming swallowed by studied masculinity.

Redundant captioning is still really annoying– what were they trying to achieve, simply repeating what the pictures were showing? Were they trying to preserve the voice and tone of radio dramas?

Fantastic piece, Chris, and thanks for counting the words.

And thank you for the insight Alex into why 35 was standard.

Gibbons not Gibson.

“That 35-words-per-panel limit was actually laid down as dogma by editor Denny O’Neil, and probably holds throughout the commercial comics industry.”

There is no industry standard for words per panel these days, if there ever was.

The rule Alan Moore uses, as stated in interview, http://mouches-d-eau.blogspot.com/2008/07/craft.html

is 210 words per page, divide by the number of panels. He attributes this to Mort Weisinger. It’s worth noting he does not appear to follow this rule in either Watchmen or From Hell, which are wordier than the rule would allow, but does appear to follow it in the ABC books and most other titles. It’s possible his thinking had changed over the years, or maybe he follows different rules for different projects. I’m not clear on that.

One might point out that Dave Gibbons drew the balloons before drawing the art in Watchmen, so it’s clear Moore could trust him to handle text- heavy pieces – while other artists would leave the ballooning to the letterer and might be less skilled in dealing with text heavy panels- so it might be safer to give them less words per panel.

Thanks, Matt. I’m king of the typos.

And thank you, Alex: I didn’t know O’Neil had made it official–a pleasant confirmation of my counting.

Kailyn: I think it was the newness of the medium and simply not knowing if readers could decode all the necessary information. Early film-makers had similar fears when innovating such now-unbelievably-standard elements as cross-editing.

“Redundant captioning is still really annoying– what were they trying to achieve, simply repeating what the pictures were showing? Were they trying to preserve the voice and tone of radio dramas?”

My cynical theory is that often the Marvel writers were doing Marvel style scripts, so really weren’t actually doing much writing, the artist was doing a lot of the writing. So the writer comes in and writes as many words as possible to mentally justify their pay check and allow themselves to feel like a writer after all.

pallas, apparently new Marvel writers were given a test: fill in the words for a 4-page section of a Fantastic Four issue. I think that’s how O’Neil got his first job.

So they were trained to fill in all the panels with words from the time of their first jobs?

It explains the wordiness folks like Chris Claremont, I guess…

BTW ironically an industry veteran told me 21st century editors would remove the redundant captions from Claremont’s scripts, he never stopped including useless captions, but apparently editors started removing them.

I think it was in the mid-eighties, after Watchmen and Dark Knight Returns, that descriptive captions, thought balloons and to some extent sound effects were beginning to be deemed uncool.

A couple of years ago Stephen King turned in a script for DC/Vertigo’s American Vampire series, and was told firmly to take out all thought balloons — “We don’t do that any more.

Alex — If I were Stephen King, I would have told the thought balloon police at DC to kiss my ass.

Arbitrary rules by self-important bureaucrats be damned. The fact is, every tool should be on the table when writing a comic book story. There is a time and place for every convention, and if a writer must go out of their way to get around using a particular tool because of some editorial edict, then the “rule” is not serving its purpose.

One point that wasn’t directly addressed was how much things changed when original art page sizes were reduced from 12″ x 18″ to 10″ x 15″ circa 1967. After that point, pages became even more cluttered with text as writers tried to shoehorn the same amount of information into a physically smaller space. The situation got even worse in the 1970s as overall page counts shrunk as well, and that, coupled with shrinking attention spans of readers, is what likely led to some of today’s anti-verbosity rules.

Personally, I’ve drawn comics using both the 12 x 18 format and the 10 x 15 format. I like the bigger size in most cases.

I also freely use thought balloons, narration boxes, or whatever else I think is necessary to properly pace a story — bureaucrats be damned.

I think the context with King was he was writing a backup story in a friend’s book. And I don’t think the lead story had thought bubbles either. And I wouldn’t assume King understood the comics medium since I don’t know if he had ever written a comic before.

I imagine the concern was King’s thought balloon based writing looked corny, like a sitcom with swirly flashbacks or any convention no longer used. You can disagree with the editor on what looks corny and dated, but it’s basically the editor saying, “you’re writing looks corny and out of touch, is that what you want”? I wouldn’t say its a case of bureaucracy, necessarily.

I disagree with anyone who argues that thought balloons are corny and dated. There are certain situations where they not only work well, they can add significant dramatic power to a panel in a way that could not be done smoothly and effectively any other way.

For example, imagine a panel where to people are facing each other, smiling, and shaking hands. The person on the left states, “It’s going to be great working on this project with you, Bob!” Bob is smiling, but his thought balloon states something like, “Yeah, you little prick! We’ll see how happy you are when I’ve finished ruining your life the way you ruined mine.”

There’s no other way to convey this tension without slowing down the pacing by adding several unnecessary panels.

Pacing in comics, as with film, is critical, and can be the difference between success and failure. I don’t know how many times I’ve been disappointed in a film or comic because the pacing and clarity were poor. Sometimes I wonder if such things are becoming a lost art.

Sorry about the typo “to” above.

One other point about thought balloons. Every single one of us thinks to ourselves a hundred times a day. Why arbitrarily pull that option from storytelling? It makes absolutely no sense.

thought balloons are still used…they just arent balloons anymore. All the captions are told in first person now, most often with a little background symbol to identify who it is who is speaking. Most comics from the past decade plus just don’t have a third person omniscient narrator anymore.

I can see how some people think they are corny, but I like thought balloons. I don’t like when the thought balloons completely describe what is happening on the panel, any more than I liked it when the captions did the same. I think though that having lost the third person omniscient narrator also severely limits the writer’s ability to tell a story how they want, just like not having thought balloons does.

I personally feel that thought balloons show a more intimate connection to the thinker–I feel that first person narration in caption boxes, while useful in some senses, creates a step of removal from the character when used on the comic page.

Bendis brought back the thought balloons for a bit when he wrote Mighty Avengers a few years back. But they were decompressed like all of his storylines and if I remember correctly, written more as a stream of consciousness. It was nice to see him try, but I thought he handled it really poorly.

“My cynical theory is that often the Marvel writers were doing Marvel style scripts, so really weren’t actually doing much writing, the artist was doing a lot of the writing. So the writer comes in and writes as many words as possible to mentally justify their pay check and allow themselves to feel like a writer after all.”

Damn, pallas, I’ve had the exact same thought. One way to back this up would be to compare word-counts in Marvel v. DC in the late 60s and early 70s — I suspect that the overwriting started at Marvel for this reason, and then spread to DC because they didn’t actually know why they were overwriting, and it just became how you wrote.

I mean, you look at an old-school guy like Robert Kanigher, and compare him with Steve Engelhart or Gerry Conway — Kanigher looks like Ernest Hemingway in comparison. Or Carl Barks or John Stanley, there’s no fat there. I don’t even think Stanley used thought bubbles or captions at all (except for captions in Lulu’s voice when she was telling a story to Alvin). It’s all on the surface with Stanley, but it’s always crystal clear exactly what’s going on. (To be fair, that’s partly due to his subject-matter)

In conclusion, John Stanley is the greatest.

I’ve noticed that when I read old comics now, I tend to skip the redundant captions — captions from which I learned SAT words like “veritable.”

Also, I picked up the first issue of the Daredevil: Man Without Fear miniseries when it came out (late nineties?), after the near-extinction of thought balloons and (I thought) the omniscient narrator. Miller’s captions were so redundant to the illustrations that I thought he was insulting my intelligence. So despite my appreciation for the character and some other works by each of the creators, I never picked up another issue.

I enjoyed Bendis’s revival of thought balloons, for exactly the reason Russ cites above. It showed the contrast between words, deeds, and thoughts, and enabled more characterization while servicing the plot. Otherwise, the writer has to portray the characters as filterless — which Bendis does sometimes — to get those points across.

There’s a parallel in prose fiction here. While it’s common to provide a character’s thoughts indirectly, quoted thoughts (“I can do this,” thought Joe) usually feel stilted–perhaps because we don’t actually think in grammatical units. Maybe I’m one of those damn bureaucrats, but I tell my creative writing students to avoid it.

Lord knows I’m not the biggest Hemingway fan, but comparing anyone to Robert Kanigher is just mean.

Surely some of it was, as well, the manga influence? Moore’s early Swamp Thing, to give one example, describes nearly every frame. He has mentioned that by the time of Watchmen he was more aware of manga.

My first comic book love, really, was manga when I was ten or so (so 1990) via french translations. When I finally went back and read many older “classic” American titles ten or so years later, I really had to adjust–it seemed less like “reading” a film where you would scan the art and the bits of dialogue and turn the page, than sitting down and reading an illustrated novel.

Since then, I’ve heard a lot of classic superhero comic book fans complain about the manga influence corrupting their books–maybe it has–but it still feels like it’s the best way to take advantage of the medium, when done right. (On the other hand, one of my favorite mangas is Miyazaki’s Nausicaa, which is filled with text.) Personally, I’ve mostly learned to see it both ways.

Some have theorized that this is because comic books came out of pulp fiction serials and magazines (at least superhero style ones did–) or serialized newspaper adventure comics which had to jam as much information into as small a space as possible given how much room the newspapers allowed them. On the other hand manga, if we see it coming out of Tezuka and his contemporaries was influenced by animated (and non animated, but largely visual,) movies.

Per Chris’s comment, I once heard a lecturer claim that Flaubert invented the technique of providing a character’s internal monologue indirectly via a third-person narrator. You know, “Joe was getting goddamned sick of the anti-word-balloon sentiment in the comics community. Forbidding the use of those balloons was like performing an unnecessary amputation–and he’d seen more than enough of those in ‘Nam. Oh, how Charlie would gloat at the horrors of war making their way to U.S. shores…” Anyway, I agree that it can work better than direct quotes of thoughts.

Actually, Jane Austen was doing “free indirect discourse” a decade or so before Flaubert was born. She’s the earliest practitioner I know of, but I wouldn’t be surprised if there were even earlier ones.

Jeez, thanks for the correction. Shows how well-read I am.

I’m agree with Chris. To me thought bubbles are more like a novel writer putting everything every character is thinking in quotes, while the Austin Method of free indirect discourse is more elegant, and more sophisticated- like one of Moore’s thought bubbles-less works.

I believe for prose novels third person omniscient point of view is not as popular as third person limited for similar reasons to the reasons thought bubbles are not popular- in real life we don’t get to read everyone’s thoughts, and when someone gives us everyone’s thoughts, unless the writer is very sophisticated, it comes across as fake or at least emotionally removed from the action.

Didn’t Moore say something about it being David Lloyd’s suggestion to abandon thought balloons (and narrative captions)in V for Vendetta, and that after initial doubts he warmed to the idea? “He trusted pictures” – quite. Or at least, he knew he could rely on who he was working with. I think it would be fair to say few mainstream comics of the 70s were genuinely collaborative works in that kind of way (love the theory that Marvel scripters were text heavy because it was the artists that actually did the work).

Don’t know about Moore’s characters talking like everyone else’s though – his ear for speech struck me as an improvement on what came before. It makes sense that more naturalistic dialogue would make thought balloons seem increasingly awkward contrived.

-sean

Noah — Kanigher is okay, at least when writing war stories for Kubert, Heath or Severin. A solid, super-competent hack who, once he’d set up the story’s gimmick (In this issue: Sgt Rock has to fight without pants), mostly got out of the way. I’d way rather read him than any of those flowery post-Stan Marvelites: Thomas, Gerber, Moench…ugh. Or Kurtzman’s war stories, for that matter. Unlike those guys, Kanigher seems to have had exactly zero literary pretensions about his audience or his own ability. (His Wonder Woman stories are shit, but, then, what would you expect?)

A thought on redundant captioning — you see it at least as far back as Little Nemo, actually. To begin with, McCay describes the action in subtitle captions…I feel like I’ve seen it in other strips from that early era, too…but gradually it fades out in McCay, I guess as he got more confident that his images could convey whatever they were supposed to.

Interestingly, Marston and Peter experimented with wordless sequences a bit. They used them several times in Wonder Woman; it worked nicely.

Sean — In 1989 I “wrote” and drew a five-page comic book story that consisted of no other words except the title, “If At First You Don’t Succeed…” and “The End.” And, in retrospect, even “the end” was unnecessary.

The reason I did this story was to prove that when it comes to comics, there are instances where a writer is redundant. You see, I’m a bit of a smart-ass, and I’m firmly on the side of the artists when it comes to the age-old comics question: Who’s more important, the writer or the artist?

That said, I know that the best comics are ones where the text and the art blend seamlessly, contributing to an experience where the sum is far greater than total of the individual parts.

This is why I bristle at the idea of arbitrarily banning narrative boxes, thought balloons, or any other comics story convention. Yes, as with my wordless story, just because you CAN do without certain things does not mean you should.

For a film parallel, think of the scene in Annie Hall in which Woody Allen and Diane Keaton are talking to each other while subtitles state their simultaneous thoughts. It creates a great comic effect, probably impossible by any other technique. Though generally speaking, I would not want to see other scenes and films with subtitles as thought bubbles.

Or perhaps a better parallel is a film that uses voice overs as thought bubbles (David Lynch did this for poor results in Dune). It’s generally very clunky, though there are exceptions, and so I would not ban the practice, but I would strongly caution against its use unless there’s a specific need/opportunity that you can’t get at any other, better way.

“there are instances where a writer is redundant.”

You have it a bit backwards, you knew what to draw because there was a “writer”- the writer is the only person starting with a blank page. They are never redundant. If the artist starts with a blank page they are a writer.

The fact that the comics industry disrespects artists who write, not crediting them as “writers” doesn’t mean that writers are unimportant or redundant.

“the writer is the only person starting with a blank page.”

??? That seems like an odd definition? The writer is the one who writes the words, usually, or the plot.

You can have an artist without a writer (covers seem like a good example.) Why not?

I was thinking of that scene in Annie Hall, too. There was a similar scene in Hate showing Buddy Bradley on a date with a woman he doesn’t like. She says, “So there we were, in the exact same outfit! I had to run back to the mall and get a new one with only an hour to go before the wedding! It was like an episode of Seinfeld!” Buddy says, “Heh heh, that sounds pretty crazy, all right!” while thinking, “Jesus Christ, ask me if I care!”

Pallas — That’s kind of why I put “wrote” in quotation marks. But what I really meant is there was no need for a separate person to “write” for the artist. In fact, in some cases, there was no need for words at all.

I guess it was my way of thumbing my nose at Stan Lee regarding his claims that he “wrote” certain Silver Age books plotted and drawn by Kirby and Ditko (especially Ditko, who he wasn’t even speaking to Lee for at least a year before he finally quit).

“You can have an artist without a writer (covers seem like a good example.)”

If there’s a narrative being told, the person who comes up with the narrative is a writer, I’d say.

Like, if Ditko said to Lee (hypothetically) “Let’s do a comic about a dude with daddy issues who gets bitten by a Spider- you write the plot and I’ll draw the pictures!” I’d still argue that Ditko was a co-writer when he came up with the concept. (I’m not saying it happened that way, I’m just making up a hypothetical) Would you say otherwise?

A cover alone isn’t a comic I don’t think, it’s more like a painting or a portrait. So I’m not sure how that’s relevant to a discussion of comics? If the cover tells a narrative its possible I’d say it’s written.

Comics don’t have to be narrative, or multiple panels. The cover of a comic is generally thought of as a comic, I’d say.

And art can be narrative too. Credit attribution depends on various things, including money, but I don’t really see the point of insisting that all plot has to be written, since one of the distinguishing features of comics is often that the story is told through art, not words.

I never said a comic couldn’t be a single panel.

I don’t see why you think the cover of a comic is thought of as a comic. I’d say the cover is thought of as a cover.

Would you also say the cover of a book is thought of as a book, or the cover of a movie is thought of as a movie? The cover of a video game is thought of as a video game? I wouldn’t, that doesn’t sound right.

I still believe that whoever comes up with the story is a writer. You haven’t really provided any benefits into abandoning that paradigm, especially in an industry with a high level of division of labor (at least traditionally and contextually in this conversation) it seems to me useful to talk about the crafting of the plot as falling under the writer’s domain. If the artist is doing it they are writing.

What benefit is there to talk about the creation of the story unrelated to writing? Does that provide any insight into the craft of comics by claiming writing is irrelevant and redundant? I think not.

R Maheras – Didn’t mean to suggest getting rid of anything arbitrarily…. Thought balloons haven’t been abandoned because they’re unfashionable (though they are that) but because other narrative techniques have turned out to be more effective. If you could find a use for them – great, whatever works.

Very much agree about seamless collaboration, which is what I was trying to get at (obviously not very well). As it happens, I think the single writer/artist is behind most of the formal innovation in comics, and the better work; Moore’s very much the exception in this regard, largely because he writes with his collaborators very much in mind. Unfortunately, his influence seems to have resulted – in mainstream anglo-american comics at least – in a fetish for the full script, with the artist conceived as the illustrator of the writer’s work.

Sean — I agree with your “whatever works” statement. I don’t agree that other narrative techniques are more effective — at least for mainstream comics.

In fact, I think I could make a good case that, as mass communications tools, they are less effective than ever. There are several reasons for this, I believe, and one of them is I think that in their quest to be more hip and sophisticated, comic book editors are actually narrowing their appeal and audience. That’s fine if one is building a business model on niche products, but such a model has never, historically, been the goal of Marvel, DC, or other large-scale publishers.

I have a hard time reading some contemporary mainstream comics. I find this alarming for several reasons. First, I’ve been reading comics, and boatloads of fiction and non-fiction, for more than 50 years. Second, my reading comprehension and such has historically placed me in the upper five percentile nationally. Finally, I’ve been a public affairs specialist for more than 20 years, meaning clear communications is always a goal of mine.

So if I have trouble reading and comprehending a contemporary comic book, then guess what? The writer and editor simply are not doing their job.

Pallas, I’d say that different things are different. A book cover isnt’ a book; a comic cover is often a comic though.

In terms of benefits…I’d say that the benefit is getting away from the idea that all narrative is written, which seems like it’s rather opposed to comics’ particular strengths, which include using images for narrative.

Prophet (the new version by Brandon Graham et al) sometimes has captions that describe what we’re seeing in the panel. (Sometimes the caption explains things that can’t be guessed at otherwise, and most of the time there’s no caption.)

My guess is that he does this to make a further connection with European sf comics from the 70s, but I don’t really know.

It’s an interesting technique.

pallas — don’t bother trying to convince Noah that a cover is not a comic; he’s said before that superhero movies are superhero comics, so…when Noah uses the word “comic”, it means just what he chooses it to mean — neither more nor less.

Carla Speed McNeill’s Finder has a novel (in comics) technique for explaining in words what you show in pictures — she uses endnotes. They don’t do it for me, personally, but it’s an interesting device.

Jones, it’s not what I choose for it to mean. Genre designations are social constructions, not formal rules. So…in my experience, people do sometimes call superhero movies comics. I find that not especially helpful, but it is what it is. Don’t shoot the messenger.

I think it is true that genre means just what we (broadly) define choose for it to mean. Genre designations are just very squishy. It always surprises me how defensive folks get when you point that out… I guess it’s because fandoms are built around genres, so saying that the genre is kind of a mass delusion makes people edgy?

Anyway, it’s a little misleading to say that the Finder endnotes explain the pictures. The often more or less deliberately *don’t* explain the pictures. Which I really like about them.

100% agree that genres are social constructions; duh. We just obviously run in very different social circles, if yours considers (a) superhero movies to be in the genre of comics, and (b) comics to be a genre in the first place (rather than a medium). Blah blah blah but the difference between a medium and a genre is itself socially blah blah blah. But bonus points for kinda-sorta suggesting that I’m just objecting because I’m an aggrieved fanboy…

You’re right about Finder. It’s a bummer that the series has never clicked for me; I really want to like it.

Noah, if

1. Genre designations are social constructions

2. The superhero movies = comics is only used “sometimes” (not typically, or usually, or often, or always)

why would you, by using the superhero movies = comics construction, help to cement that construction, when you don’t find it “especially helpful?”

I don’t know how much I helped to cement it? I mean, I don’t remember what Jones is referencing, but I think if I said, lots of people seem to think that superhero films are comics, I would have said it that way. Not, “superhero films are always comics!”

I guess I should say, I could see that construction being useful sometimes. Not if what you want to talk about is comics formal structures, but maybe if you wanted to talk about the way that superheroes as a genre have been synonymous with comics for lots of people.

Jones; I wouldn’t say it’s different social circles. It comes up sometimes on comments threads.

Fair enough Noah. I have no idea what the original context is either, so I probably shouldn’t have stepped in.

I have seen cases where someone assumes that comics (comic books to be more precise) consist of super-heroes. But I’ve never seen the construction that super-hero movies are comics.

Just wanted to add that a recent issue of Matt Kindt’s Mind MGMT had a “silent” issue that was all thought bubbles. A very wordy “silent” issue where all we “heard” was what people were thinking.

It was issue #21

Chris, I know I’m returning to this thread long after the dialogue stopped, but in retrospect, I think your response to Kailyn about creators not trusting the young medium were correct. Furthermore, I think they were correct, too.

Geeks like us can tell what’s going on in a sequence of panels fairly easily, even if the storytelling is mediocre. I’ve learned as I’ve introduced comics to non-readers that not everyone can do that. Even very bright people can become flummoxed over what panel to read next when the artist deviates from the standard grid. It can be even more difficult to understand what’s happening among and between those panels. This severely degrades the enjoyment derived from reading comics. The heavily captioned and thought-ballooned comics of the past were a giant step closer to illustrated novels than the taciturn visual narration of today. Maybe entry-level comics should have those captions. Maybe all the digital comics should have them as a toggle-switched option. Otherwise, the creators continue to serve a small and dwindling number of sophisticated palates.

John, that reminds me of showing Frank Miller and Bill Seinkeiwicz’s Elektra to my father. A very bright guy who grew up on golden age comics, but he couldn’t decode the first page because it bent so many conventions.