I belatedly read Philip Sandifer’s A Golden Thread: An Unauthorized Critical History of Wonder Woman earlier this week. As the title says, this is a blow by blow reading of basically every Wonder Woman comic-book iteration from Marston all the way on up through Azzarello. It’s similar in focus to Tim Hanley’s Wonder Woman Unbound — though Hanley lets his focus drift a bit more, talking about other female superheroes, talking in depth about the matriarchal theories held by Gloria Steinem’s circle, and generally trying to position Wonder Woman as an important cultural force, or at least a center of interest. Sandifer is more committed to close readings of the comics (and the occasional related media property).

In some ways, then, Sandifer’s book has the same problem as Hanley’s only more so; that problem being, it’s not entirely clear why anyone would want to do close readings of all Wonder Woman comics from the primordial ooze to the present, given that (a) they were mostly horrible, and (b) they weren’t at all popular. Why does anyone want to analyze the ways in which this particular unread piece of pulp detritus is mediocre? Why would anyone but hard core fans want to read it? It seems like Sandifer has consigned himself to a misty, bleak pop purgatory, following that golden thread into a bland, milk-covered bog.

Given that he’s in that bog, though, there’s something heroic about Sandifer’s determination to wade through it. The entire history of Wonder Woman comics doesn’t really deserve a decent chronicler, but Sandifer nevertheless determines to provide it with one. His writing throughout is elegant and entertaining and even, almost impossibly, passionate. His respectful, fair, and blistering denunciation of Gloria Steinem’s blinkered take on Wonder Woman, feminism, and (not least) trans people is a highlight, but it’s got lots of company, such as the brilliant discussion of Harry Peter’s art, tracing it to Victorian pornography and Beardsley. His readings hardly ever dovetail with mine; he thinks the I Ching era was exciting and ambitious; I think it was largely dreck; he thinks Greg Rucka brilliantly incorporated Wonder Woman’s history of bondage imagery into the Hiketeia; I think Greg Rucka is a humorless, pompous ass; he thinks Marston was an interesting creator but not a genius, etc. etc. But Sandifer always makes a stimulating case, and if I think his Greg Rucka is a lot smarter and more sensitive to the character’s hsitory than the real Greg Rucka — well, that just means I got to read and enjoy that Wonder Woman story Phil Sandifer wrote. If DC was smart (which they are not), they’d hire Sandifer to write their Wonder Woman comics for them.

Anyway, I thought I’d just quickly talk about one of Sandifer’s discussions which I found intriguing. In his analysis of the Lynda Carter Wonder Woman series, he references Laura Mulvey, and notes that her ideas about the gaze seem to work uncomfortably well; Carter, he says, is consistently framed by a male gaze. For instance,”Shots in which the camera tracks the eye movements of male characters looking at Lynda Carter (whether as Wonder Woman or Diana Prince) are exceedingly common. Scenes where Diana and Steve talk in his office are routinely shot with the cameras positioned behind Steve’s desk.” Sandifer goes on:

Of course, Wonder Woman has always been overtly sexualized. Marston’s conception of her as a figure to which men would willingly submit is still based on the external idolization of women by men. But there’s an intrinsic difference between the sexualization of an ink drawing and the sexualization of an actual human being. Carnal desires projected on a page of ink necessarily exist entirely within the realm of imagination. The sexualization of Lynda Carter has an actual person as the object of desire.

Sandifer adds that Lynda Carter herself found the sexualization and objectification unpleasant; in a 1980 interview she said “I hate men looking at me and thinking what they think. And I know what they think. They write and tell me.”

Sandifer draws a distinction between Mulvey’s gaze and sexualization in comic books on the grounds that in film (or television) a real person there’s a real person being gazed at.

I think that’s an interesting take on Mulvey’s theory…but it’s not exactly the theory itself, at least as I understand it. Mulvey’s ethical argument against narrative cinema is not against the sexualization of people, but rather against the way that gender roles are inscribed through the power of the camera placement. I’m sure Mulvey would feel that Lynda Carter’s discomfort emphasizes and extends the criticism she was making…but the criticism doesn’t rely on that alone. Rather, Mulvey’s point was that narrative cinema inscribes men as the looker/doer, and women as the fetishized object of the gaze on whom the male looks/does. Narrative film is denigrated not because it makes individual actresses uncomfortable, but because it seduces its viewers to acquiesce in stereotypical and sexist gender roles.

And I would say that this is something that comics can do as well.

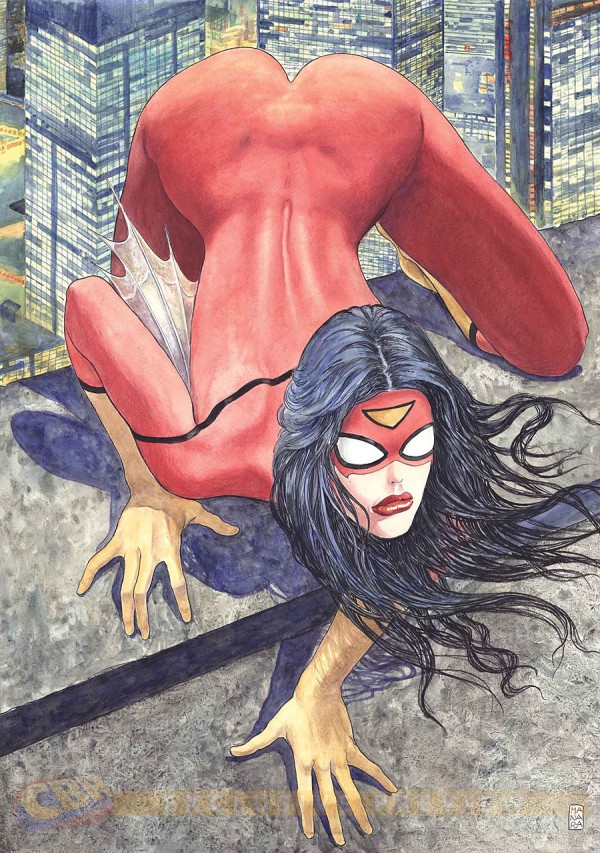

This is a rather obvious example — but still instructive, I think. The pose here is deliberately designed to draw attention to the rear, and especially to what people in those neighboring buildings might possibly see, but which you can’t. The cover encourages you to mentally take Spider-Woman and turn her. There is no narrative, per se, but there remains the sadistic association of viewer (figured here pretty clearly as male) with action performed on a woman, who is frozen and fetishized, her individual body parts (the rear, the invisible crotch) presented as consumables.

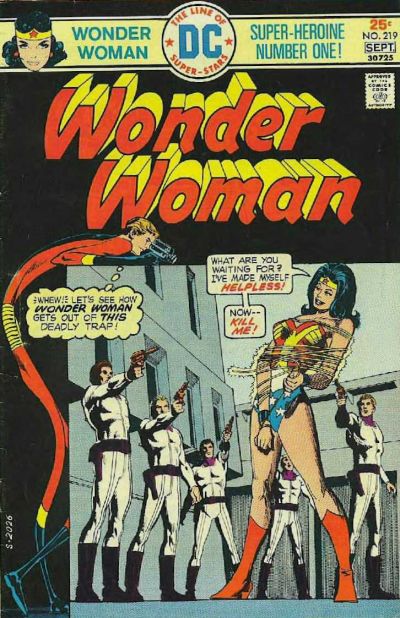

And for an example featuring Wonder Woman, how about:

That’s a cover (Update: by Dick Giordano) to a comic by Martin Pasko and Curt Swan. Sandifer argues that the comic itself is intentionally and effectively feminist — which may well be. The cover, though, seems like a textbook example of Mulvey’s theories. The Elongated Man, that virtual double-entendre, looks at Wonder Woman through a video camera while a circle of men point their phalluses, er, guns at her. Tied up, Wonder Woman coos with a come-hither tilt, asking to be “killed”, her hand hovering over her crotch. The heroine is immobilized by and for the male gaze, begging for action that is figured, not especially subtly, as sexualized violence. And note especially that the reader is specifically positioned with, and encouraged to identify with, the male with the camera; we are supposed to watch with Elongated Man, the good guy who stares at the willing, supplicant woman.

The bondage there is of course a holdover, and perhaps a nod, to Marston.

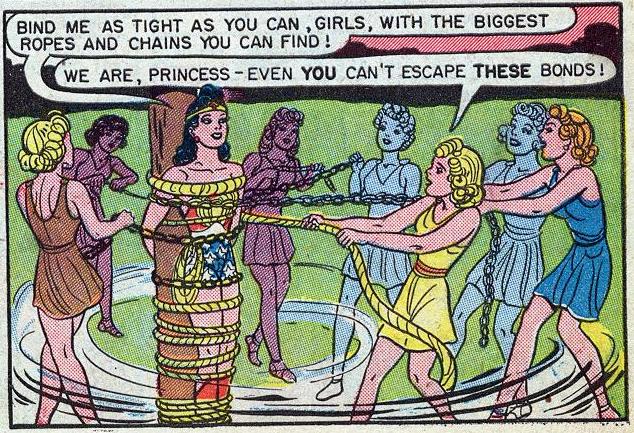

Marston just about never fits that easily into Mulvey’s formulation, though. In this panel, for example, there is no man gazing; women are the actors, whooshing about with Peter’s energetic motion lines. But more than that, the motion, or the narrative, is not linear; the Amazons can be seen either as a group in motion, or as one replicating individual racing around the pole, a rushing frozen sequence of bodies with Wonder Woman at the fulcrum. The narrative is frozen in fetishistic contemplation of women…but it’s also a rush of motion, a narrative that doesn’t go anywhere, or need to go anywhere. The (male or female) viewer, is frozen giddily like Wonder Woman, watching without motion a motion that goes nowhere. Mulvey argues that women “connote something that the look continually circles around but disavows: her lack of a penis, implying castration and hence unpleasure.” But the circle here doesn’t disavow the lack of a penis; rather it glories in it, as the still observer is merged with the still, bound woman in a game of delightful submission to disempowerment. Mulvey argues that narrative cinema is about denying male castration; Marston’s gaze, on the contrary, embraces it as an exciting option for children of every gender.

________

Sandifer’s A Golden Thread is available here.

And, as you probably know, you can preorder my Wonder Woman book and read more about the joys of castration here.

In that last panel, how did anyone think of a lack of a penis (whether that’s a good or bad thing)? Nothing really indicates a phallus (or lack thereof).

Well, I’m working off of Mulvey, who sees women themselves as embodying the idea of “lack of phallus.”

Why does Ralph have a camera? That’s particularly lurid.

Diegetically, it’s part of a series where members of the Justice League monitor Wonder Woman to see if she should be let back into the club (after she lost and regained her powers.)

It’s a distasteful and bone-headed premise; I think the main purpose was to have crossover guest stars for a number of issues in the hopes that that would make someone (anyone!) read Wonder Woman comics.

Sandifer likes Pasko’s run pretty well and makes a nice case for it. I can’t say I was exactly convinced though.

That Pasko and Swan cover is almost absurdly voyeuristic, there’s literally a little man who is elongating pointing a camera at wonder woman’s tits. I’m tempted to ask if there’s anything ironic or satiric about it? Though from your explanation of why the elongated man is there I suspect not.

On an unrelated note, does anyone else get strong Darger vibes from the Marston drawing? I wonder if Darger would ever have used any of Marston’s comics in his own work, it seems a little too late to be a huge influence on Darger, but there seems to be a common theme and feel to the work.

Sandifer argues that Pasko is conscious of feminist issues, and that the comic is engaged with feminism, so I guess based on that you could make the case that it’s satirical (WW will break the chains and overthrow, etc.) However, the fact that the main voyeur here is the hero makes it difficult for me to see the cover itself as satiric or especially thoughtful. Or I guess, it might be intentionally hyperbolic…but the Manera cover is intentionally hyperbolic too. I think exaggerating tropes doesn’t necessarily amount to a critique in a situation like this.

I’ve noted the Darger connection before. I suspect that it’s about shared influences; both Peter and Darger working off of Victorian imagery (and possibly Victorian pornography.)

I agree, it would require a level of subtlety I wouldn’t expect from DC, and yeah, I think it’s definitely hyperbolic – but as it is its just replicating the sexualization not criticizing it.

I was thinking the same thing about shared influences, it is intriguing that two of the more interesting artists coming from that background are so obsessed with the placement of the penis on their characters, maybe just a coincidence though, I don’t know nearly enough about victorian comics and porn to work out if there’s any connection.

”That Pasko and Swan cover”

The art’s actually by Dick Giordano.

Ahhh…I wasn’t sure who the cover artist was. Thanks Alex.