I don’t know if Victor Hugo was gay. But I do know he wrote some of his most influential work from exile—including political pamphlets, three books of poetry, and Les Misérables, a historical novel about the French Revolution that he “meant for everyone.” Hugo describes it like a superhero answering a cry for aid: “Wherever men go in ignorance or despair, wherever women sell themselves for bread, wherever children lack a book to learn from or a warm hearth, Les Miserables knocks at the door and says: ‘open up, I am here for you.’”

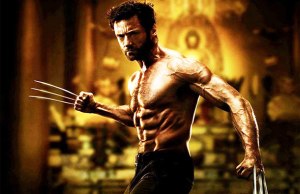

I did not see Les Mis, either on stage or on screen, but my kids went with their Nana after my wife and I escaped for our own outing: fancy dinner (turns out steak tartare is a raw hamburger), romantic movie (Jennifer Lawrence is a shape-shifting genius even when not playing a blue-skinned mutant), and historic B&B (former haunt of musical legend Oscar Hammerstein). We had a better time than the kids. My son was not wooed by Hugh “Wolverine” Jackman, and my daughter would not list on-set singing among his superpowers.

But the X-Men casting choice did spotlight some secrets in the musical’s origin story. Both literary blogger Chrisbookarama and Slate culture editor David Haglund declared Jean Valjean a “superhero.” They note his dual identity (alias “Monsieur Madeleine”), his superpowers (the strength of “four men”), and his arch nemesis, Inspector Javert (inspired by real-life detective Eugène François Vidocq). There’s even an unmasking scene:

“One morning M. Madeleine was passing through an unpaved alley” where an “old man named Father Fauchelevent had just fallen beneath his cart.” A jack-screw would arrive in fifteen minutes, but “his ribs would be broken in five.” Madeleine sees “there is still room enough under the cart to allow a man to crawl beneath it and raise it with his back,” and he offers five, ten, then “twenty louis” to anyone willing to try. Javert, “staring fixedly at M. Madeleine,” declares: “I have never known but one man capable of doing what you ask.”

Although Valjean is breaking the law by disguising his past as a convict, he “fell on his knees, and before the crowd had even had time to utter a cry, he was underneath the vehicle.” Even the old man, “one of the few enemies” Valjean has made as Madeleine and then only from jealousy, is begging him to give up, when “Suddenly the enormous mass was seen to quiver, the cart rose slowly, the wheels half emerged from the ruts,” and “Old Fauchelevent was saved.”

“Just like a superhero,” writes Haglund, “outed by the noble use of his super strength.”

My daughter assured me the film framed it as a burst of Hulk-like adrenaline, but Victor Hugo was going for much more. Although Valjean emerges in torn clothes and “dripping with perspiration,” he “bore upon his countenance an indescribable expression of happy and celestial suffering” as the old man calls him “the good God.”

It’s the self-sacrificing yet self-ennobling choice saviors make every day. Even Jesus in Martin Scorsese’s Last Temptation of Christ wants to hide in a mild-mannered lifestyle, before fully accepting the job of super-savior. Ditto for Tobey Maguire’s Peter Parker and Michael Chiklis’s Ben Grimm. A hundred years earlier, O. Henry’s safe-popping Jimmy Valentine outs his Valjean past by saving a child from suffocating in the town bank vault. Philip Wylie’s superhuman Hugo Danner longs for the quiet life too, but fate slams another would-be victim into another character-revealing bank vault.

And there’s always a Javert standing right there trying to glimpse your secret self. Jimmy has detective Price on his trail (though in a typical O. Henry twist, he lets his Valjean go). That pesky tabloid reporter followed Bill Bixby for five seasons, always ready to snap a picture when Lou Ferrigno burst out during the emergency-of-the-week. Like Les Mis director Tom Hooper, the CBS team decided their Incredible Hulk was just a burst of green adrenaline, the kind that allows Clark Kents to shoulder cars off endangered loved ones. That’s the phenomenon Bixby’s Banner is researching before his laboratory mishap, his atonement for failing to save his wife when fate dropped Fauchelevent’s oxcart on her.

But Haglund’s comment unmasks another kind of outing. When my former department colleague and next door neighbor Chris Matthews read that Slate article “Why Tween Boys Love Les Miz,” he emailed me about Hagland’s “silent premise,” the implication “that there’s something weird about boys liking musicals.” And we know what alter ego lurks under that tale-tell proclivity. “The figure of the musical-loving boy or man,” says Chris, “has long functioned as both an element of gay male identity and as a handy stereotype for mocking ‘effeminate’ men, gay or not.”

I noticed plenty of family photos decorating the Hammerstein B&B, evidence that Rodgers was his partner in the strictly professional sense. But it did occur to me to check. GLBTQ, the online encyclopedia of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender & queer culture, lists Hammerstein as “apparently quite straight,” but the site still can’t explain “the attachment many gay men have to the musical theater or the fact that in the popular imagination a passion for showtunes is practically a marker for homosexuality.”

Les Misérables premiered in 1980, twenty years after Hammerstein’s death, ninety-five after Victor Hugo’s. I was fourteen, Chris’s age when he saw it on stage. Haglund was nine his first time, so his pubescent body wasn’t bursting through his sweaty clothes just yet. Maybe that’s why he remains a tone-deaf Javert when it comes to identity-shifting. He sounds relieved that a superheroic explanation for Miz-loving boys hit him while watching Jackman belting it out. Why Do Tween Boys Love Superheroes? Because they’re not “weird.” He thinks his men-in-tights insight is “more particular” to boys, even though both sexes get equally erotic eyefuls of Jackman’s shirtless flexing. Sorry, David, but as my former neighbor points out: Hugh is hot.

Chris, by the way, is not gay. At least not in the I-like-to-have-sex-with-other-men sense. Like my and Hammmerstein’s homes, his is decorated with family photos. He claims to be “terribly low on football-related and power-tool-based conversation,” but wow can he unman me on a racquetball court—an advantage none of my Hulk-like adrenaline can match. Chris also grew up in the apparently quite straight world of comic books. While his tween-self was singing along to the Les Mis soundtrack, he was flipping pages of Spider-Man and Moon Knight. “Superheroes were not the guise of normalcy I wore over the shameful secret of loving a musical,” he says, “they were yet another way of getting around the pressures to be normal.”

Saturday October 11 is National Coming Out Day. It’s not a Revolution. It’s just a celebration of the superheroic who continue to overthrow the pressures of the so-called normal. I wish them all a safe return from their personal exiles.

There are other curious Victor Hugo/superhero connections.

Quasimodo, the hunchback of Notre Dame, is arguably kin to monstrous heroes like the Hulk and Man-Thing.

Bob Kane claims (take it with a grain of salt) that the Batman arch-villain, the Joker, was inspired by a still of Conrad Veidt as Gwynplaine, the tragic hero of Hugo’s The Man who Laughed, in a silent film adaptation.

Check these images out to see if there’s anything to it.

Of course, Kane’s assistant Jerry Robinson claims that he based the Joker’s design on a Bikes playing card.

Here’s Robinson’s claimed design.

No word on Bill Finger’s role…

It also strikes me that there’s a distant superheroic echo in the death of young Gavroche at the barricades. He’s shot and falls to the ground:

“But there was an Anteus in that pygmy. A Paris urchin who touches the paving-stones of his city’s street is like a giant drawing strength from the Earth.”

I clearly need to read some more Hugo!

And as far as Finger’s role in creating the Joker:

https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2014/03/unmasking-the-joker/

I don’t know why it bothers me, but it seems weird to talk about a musical as comic book movie rather than talking about comic book movies (or comic books) as musicals. I think it was Steven Grant who wrote that fight scenes are to comics what musical numbers are to Broadway (or something like that). And if we want to go all “anxiety of influence” with this, we could probably argue that both genres inherited certain formal features from the opera.

Back to the essay’s point about masculinity, I wonder if camp is the operative signifier. Camp underwrites the real or perceived associations between musical theater and gay culture, and camp is that which current superhero movies try desperately to avoid, or closet (memories of the Batman 66 TV show, the George Clooney Batman). Instead, we get something closer to a sports and power tools aesthetic (manly boys with manly toys), which is the current, socially accepted way to manifest homosocial relations.

I think you’re on to it, Nate. Performing a superhero in a campy style mocks standard definitions of masculinity, which upturns the heterosexual framework. But I’m not sure all or most musicals are campy–at least not intentionally campy? Perhaps the inherent absurdity of the performance context (the fourth wall, there’s music coming from nowhere, and now I’m singing my inner most thoughts) has the same effect as camp?