I made a strange discovery recently. Reading the Delta Green Call of Cthulhu RPG sourcebooks for a different perspective on the H.P. Lovecraft narrative (as well as to interact with and enjoy one of my favorite literary worlds), it occurred to me that a great deal of the current literature coming out of the forever war in Afghanistan and the Middle East are basically horror stories.

I made a strange discovery recently. Reading the Delta Green Call of Cthulhu RPG sourcebooks for a different perspective on the H.P. Lovecraft narrative (as well as to interact with and enjoy one of my favorite literary worlds), it occurred to me that a great deal of the current literature coming out of the forever war in Afghanistan and the Middle East are basically horror stories.

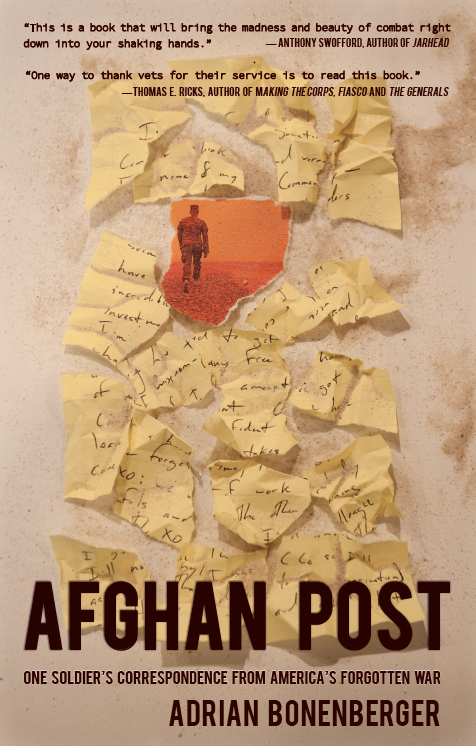

Much of the current literature on war comes to us in the form of memoir. Many of these accounts focus on special operations soldiers such as SEALs, Rangers, Delta, CIA, or mercenaries formerly employed by one of these groups. The bulk of the remainder of the memoirs are firsthand accounts produced by combat veterans from regular units. My own memoir, Afghan Post, is an epistolary account drawn from journal entries and letters to others during my time deployed. LTC Peter Molin, who reviewed Afghan Post for his blog Time Now (detailing war-themed literature) said that it reads like bildungsroman – a coming of age story.

Meditating on Lovecraft, though, I realized that my memoir makes a lot more sense as horror, and I suspect that this holds true for a great many of the war memoirs we’re used to encountering as non-fiction essay.

For those unfamiliar with H.P. Lovecraft it’s probably worth making a wild overgeneralization and claiming, briefly, that he was responsible for establishing the genre of modern horror as we know it. In Lovecraft’s stories, a protagonist who operates on the fringes of society (private detective, university researcher, scientist, a relative to some obscure and eccentric person) is presented with a mystery about the nature of the universe. The solution to the mystery is either some horrifying revelation about the nature of the universe that drives the protagonist mad, or a monster that kills the protagonist.

Given the frame of a universe wherein people are killed or driven mad by what they see and do, it’s not difficult to see how war memoirs or any trauma story could lend themselves to comparison and analysis. Most contemporary participants in war (who are, in America at least, all volunteers), elect to take part in state sanctioned violence. Whether they are shooting at enemies or being shot at, the emotional progressions moves in most cases quite naturally and predictably from some form of idealism to realism and, ultimately, to pessimism (and, frequently, to suicide as well).

I first encountered H.P. Lovecraft in a Borders in Evanston, in winter of 1996. A classmate of mine, Scott Richardson, introduced me to the author when I expressed an interest in reading short horror fiction, and fatigue with Stephen King (who has also produced an incredible body of short horror fiction, for which he should be always and best remembered). Lovecraft made effective use of the epistolary device in his horror stories –At the Mountains of Madness, for example, is a novella told through the journal of an explorer and scientist in Antarctica who makes a horrible discovery. Used appropriately, the frame allows readers to experience, firsthand, the dissolution of a mind, and undergo in hours what would otherwise transpire over a course of days, weeks, or more.

When people have asked me what my inspiration was for framing Afghan Post as an epistolary memoir, I’ve told them the truth: I’ve always enjoyed writing letters and journal entries, and I found the writing of difficult personal material to be easier if it were addressed to the friends and family with whom I’d actually corresponded during my deployments to Afghanistan. A friend had sent me a copy of Les Liasions Dangereuses shortly before I began writing my memoir, so that book – told through a series of letters between two French aristocrats – was also very prominent in my mind. It did not occur to me that, in telling the story of my psychological fracturing, and splitting, I was evoking Lovecraft.

That connection works both ways, broadly speaking – Lovecraft’s stories are filled with references to war, and especially World War I. Oftentimes a character will be revealed to have been a veteran of that conflict –not surprisingly, given the time during which Lovecraft was writing, but not often remarked upon in literary studies. And nowhere moreso than in his short story The Rats in the Walls, where the narrator’s son dies from a wound inflicted in World War I, and another World War I veteran is murdered under suitably terrible circumstances – in the earth, among the scurrying of rats, which were a powerful symbol of trench life, as well as life in the hellish, muddy wasteland between trenches.

The book I wrote is the story of an intellectual and artistically inclined young man, who encounters the terrifying reality of life outside the safe confines of the developed world, and endures the emotional consequences. Reading Afghan Post now, ten months after its release and nearly a year and a half since I last edited the text, I must admit that my journey concluded with a descent into madness, from which I have only partially recovered.

While it’s irresponsible to make generalizations about something as wide and all-encompassing as war literature, which runs the gamut from fiction masterpieces like Slaughterhouse Five to first-person memoirs like the controversial American Sniper, my own sense of the war narrative is this: there’s something to the process of going to war that undermines the confidence we veterans have in a naturally or passively just world. I’m surprised it took me this long to realize that I wrote a story that could honestly be described as “Memoir – Epistolary – Horror.”

War memoirs are so tied to authenticity claims, it’s interesting to think about the way something like Lovecraft might affect them. And that’s a nice point about the effect of WWI on Lovecraft’s writing too.

Adrian, have you read Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula? It’s obviously horror, and it is told in a masterly epistolary frame — using letters, diaries, press clippings, even a phonograph record. I have no doubt it influenced Lovecraft’s ‘The Call of Cthulhu’.

Alex – I have, and of course you’re right. Frankenstein is epistolary as well, the 19th century seems to have enjoyed the form. Both of those stories must have influenced Lovecraft deeply, and I’m going to spend time reengaging the texts and meditating on the specific parallels between them.

One place in which they don’t overlap – Dracula / Frankenstein and Lovecraft’s world – is that there is no Christian God in Lovecraft. There is no possibility for redemption, only death or madness. Thanks for broadening the scope of my inquiry – as you can tell it’s still quite young!

Just a side note, the epistolary novel was not all that popular in the 1900s, and indeed would have been seen as distinctly old-fashioned, having had both its heyday and its satirized decline in the previous century. It is interesting however that it remains useful within various forms of what comes to be called genre fiction: Shelley’s science fiction; (some of) Poe’s and Lovecraft’s tales of the fantastic; Collins’s detective stories; and Stoker’s Dracula, plus its predecessor, “Carmilla.”

Ironically, the form — which started off as combining both documentary and psychological realism (“this really happened” plus “this is what it was like as it was happening” — what Richardson called “writing to the moment) — came to be seen as distinctly un-realistic, stilted, overly artificial and mediated. Then, in the 19th century, it’s taken up (sometimes) by authors who are trying to create stories are un-realistic and exaggerated to their core, again trying to give the impression that “this really happened” but in a way that highlights the fragmentary, uncanny, and distant nature of that documentary evidence. It becomes as much about not-true and the not-here as the converse.

There have been epistolary novels drawing on modern media.The Anderson Tapes was a caper book consisting entirely of transcripts of tape recordings.Martin Lukes was told through e-mails and IM.

The diary novel is still going strong, notably through the Bridget Jones and Adrian Mole books.

Yep, Yep. The epistolary novel seems to be especially big in the YA market, standing as a marker of novelty (sometimes) and authenticity (always). But the latter puts it at odds with what you folks are noting about the form.

Diary of a Wimpy Kid is a huge YA bestseller, with lots of ripoffs.

Peter – I think that’s a big part of the form, the tension around authenticity. One of the primary concerns around war narratives happens to be the value of experience – whether or not being in combat makes the author more or less credible (many “literary” authors would say less credible, most matter-of-fact memoirists would say more credible). The essential marketability of a certain type of memoir basically depends on whether you believe that, say, a guy like Chris Kyle recorded 150 sniper kills, or whatever the total was. Or that the author of “Carnivore” killed 2,000 Iraqi insurgents. If you think that this makes their experience somehow special or exceptional, it means you buy into the idea that experience itself has a special weight – Tim O’Brien, in “The Things They Carried,” avers the opposite. He writes “to generalize about war is like generalizing about peace. Almost everything is true. Almost nothing is true.”

Thanks for the thought-provoking observations!

Many people thought Stephen Crane was a Civil War veteran after he brought out The Red Badge of Courage. In fact, the novel came out of research and imagination.

Epistolary horror lives on in film, in the “found footage” subgenre. It has the same pros and cons there as in prose — on the one hand, it promotes putative realism and motivates a restricted pov; on the other hand, why in gods name are they still filming while the monster is chasing them?

Hah! That’s a great point; I’d never thought of found footage as updated epistolary.

It is a great point. It got me wondering about how one could create an epistolary comic– and then it hit me: screenshots!

Each panel could be a fictional ”screenshot” from a blogpost, a tweet, a Facebook update, etc…