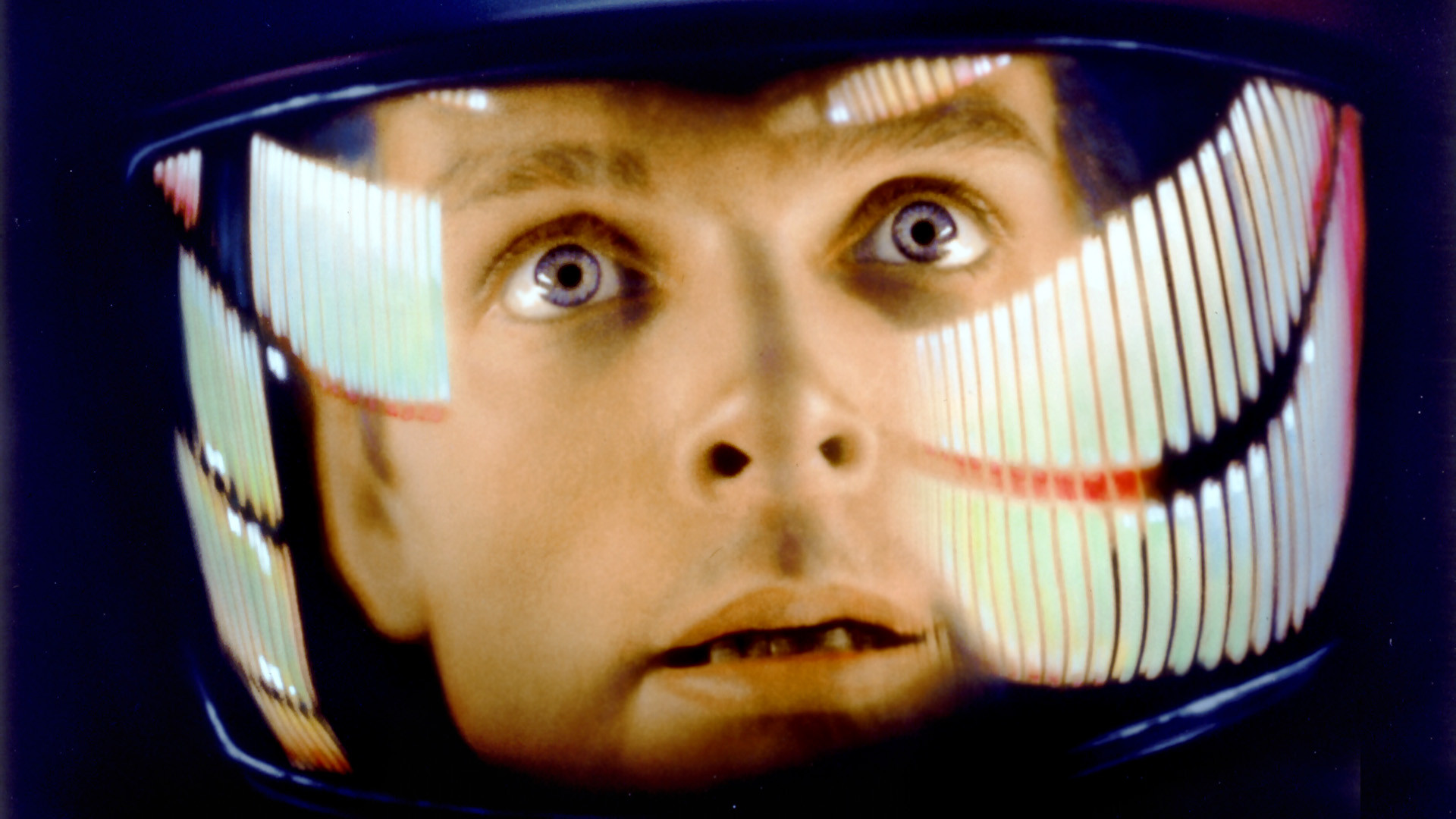

Arthur C. Clarke (1917 – 2008) was one of the most prolific science-fiction authors of the 20th century. His body of work includes more than a dozen novels, more than 100 short stories and even a few non-fiction books. His magnum opus was perhaps the screenplay for the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, written jointly by Clarke and director Stanley Kubrick as an adaptation of one of Arthur’s short stories. 2001 has been viewed by millions and has become an iconic cultural touchstone.

Now that several decades have passed from the time Clarke started writing, it has become clear that he was not just an imaginative and talented author, but also a prescient prognosticator of the future. Many of the technologies that Clarke envisioned have become commonplace realities. This may be a case of life imitating art because many young scientists and engineers were avid fans of his, so his writings themselves may have influenced the development of the modern technological landscape.

In 1945, Clarke wrote a paper entitled “Extra-Terrestrial Relays – Can Rocket Stations Give Worldwide Radio Coverage,” describing satellites using geosynchronous equatorial orbits to facilitate worldwide communications. Clarke’s article initiated an interest in the subject – in the 1960’s, together with Howard Hughes, NASA began work on the Telstar project (which would ultimately culminate in satellite television broadcasts and the HughesNet data satellite networks as they exist today). The first satellite using the principles outlined by Clarke was launched in 1964, and they are now extensively employed in meteorology, mobile phone communications and radio and television broadcasting. His contributions to the field are reflected in the fact that these geosynchronous orbits are also called “Clarke orbits.”

Even more striking are Clarke’s frequent pronouncements on devices that ordinary people would use in their homes. In a 1964 documentary broadcast by the BBC, he noted that “trying to predict the future is a discouraging, hazardous occupation,” but he nevertheless continued on to give his predictions for the coming decades. Clarke foresaw what he called a “replicator” to reproduce physical items along the same lines that documents and photographs can be copied. 3D printers are now turning this vision into reality. In the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, astronauts aboard a spaceship used “newspads,” which bear a remarkable similarity to today’s tablet computers, to watch a TV interview. In 1974, Clarke stated that people in the future would have small computers in their own homes in contrast to the bulky, business-oriented machines then in use.

Rather than just imagining the physical devices that would be built, Clarke focused on the changes they would bring to human society. He believed that people would be able to get in touch with their friends all around the world easily as well as look up their bank records and theater reservations right from their computers. He thought that these small, household computers would become ubiquitous and would enable people to work far away from their offices. He even predicted the rise of telemedicine, and the future of robotic surgeries. All of these seemingly farfetched shifts in lifestyle have become largely true, at least in many wealthier countries.

Of course, not all of Arthur’s conjectures turned out to be accurate. His idea of people using monkeys as personal servants still seems as unlikely today as it did when he pronounced it. Likewise his suggestion that people would dwell inside giant domed communities on the north and south polar ice caps. Nevertheless, wild guesses of what’s to come in future years are typically left to psychics and dreamers – whose predictions aren’t often accurate. Arthur C. Clarke’s unique genius enabled him not only to see into the future, but nudge his futuristic visions towards reality.

Actually, trained monkeys are used to assist quadriplegics.

Alex — Monkeys are old stopgap “technology” compared to brain-activated devices that are quickly advancing and becoming available to people with limb or mobility issues.

Back in the early 1980s, after being trained to repair advanced aircraft avionics systems, it became apparent to me that it would eventually be possible to bypass damaged nerves, allowing the paralyzed to use “dead” limbs and even eventually walk.

We’ve actually gone far beyond that. In the very near future a complete quadriplegic may be able to use brain waves and an exoskeleton to move around fairly normally.

We’re also toying with growing tissue, bone and organs, so we may eventually be able to repair and/or replace things that in the recent past would have been thought to be impossible.

Clarke was right about the hazards of making predictions, but as Jared points out in his essay, Clarke was pretty good at it. The key to doing so, I think, is an open mind (scientists, like any other experts who rest on their laurels and frequently “fight the last war,” can be notoriously closed-minded), and a good basic understanding of many, many areas of science.

I can’t remember the author — maybe George Friedman? — who pointed out that predicting technological change is much easier than predicting sociological change. Whoever it was used Jules Verne’s stories as examples.

I just reread 2001, and kind of can’t believe how lousy it is. The New Age nonsense is completely vapid, the prose is studiously flat, and the characters are blank ciphers moved from one “awe-inspiring” vista to the next. Hard to believe this stylistic and intellectual nullity is considered some kind of high-water mark of the genre.

Well, the movie was good, anyway.

I just watched Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?, Michel Gondry’s animated interview with Noam Chomsky, and one of Chomsky’s comments reminded me of the opening scene of 2001. He said that modern humans’ capacity for planning and language probably didn’t evolve gradually but began with a mutation in a single pre-human. I was kind of surprised that Gondry didn’t immediately mention the Monolith.