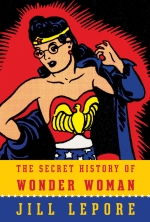

Earlier this week Jeet Heer and I had a long conversation about Jill Lepore’s Wonder Woman and it’s strengths and weaknesses. Comics scholar Peter Sattler weighed in with a long comment, which I thought I’d highlight here.

Earlier this week Jeet Heer and I had a long conversation about Jill Lepore’s Wonder Woman and it’s strengths and weaknesses. Comics scholar Peter Sattler weighed in with a long comment, which I thought I’d highlight here.

Just finished the book, Noah, and I hope you won’t mind if I use this as a place to write a few thoughts, which I think intersect with your conversation.

1. Lepore’s lack of engagement with more current Wonder Woman scholarship, at least in her notes, is striking, especially considering her attention to far more recent writings on such figures as Wertham (e.g., Beaty, Tilley). Nonetheless, I think that Jeet’s genre-based point speaks a bit to this: Lepore is not invested in the “secrets” of today, as much as the secrets of yesterday — the past that ends mainly with her narrative, in the 1970s.

2. That said, I take Noah’s point about how the issues of queer identities — and even the practices of queer life in mid-century America — is barely a topic for this book. Lepore actually spends little time talking about sex, sexuality, or theories of same (Marston’s or otherwise). Dramatically more space is given over to issue of suffrage, to the economics and power dynamics of women’s work, to the lie detector and its place in the juridical-military system, and to the shitty way that women are treated by men. The material on sexuality is there, but hardly dwelt on or analyzed. Indeed, with its New Age and Aquarian designations, Marston’s ideas about love and submission as much an object of fun as anything else.

3. But to be clear, the lack of a “queer” history or theoretical context is certainly intentional and not an oversight. The “secret history” of Wonder Woman, for Lepore, is not a secret of sex or love or the closet; it is a secret history of politics. It is a story of the deep roots of feminism: it’s about the fight for women’s rights. (Even the discussion of chains, for example, focuses far more explicitly on its ties to feminist imagery than to kink.) And the book’s commitment is to tracing those roots as thoroughly as possible. An alternate title might have been “the political origins of Wonder Woman.”

4. Pace Noah, I don’t think Lepore does much to privilege her own or her reader’s sleuthing skills. Unlike her New Yorker article, Lepore never puts herself into this story, trying desperately to break through the walls of silence. The “secret” framing — just like the academic framing — is actually pretty thin. It’s the intersection of documents and stories in the middle that counts.

5. When it comes to the “waves of feminism,” Lepore both wants and does not want to make the argument that seems to be promised. She definitely has a passage on the forgetfulness of the radical wing of the second wave, with Shulamith Firestone visiting Alice Paul and not being able to identify portraits of the nation’s most famous feminists (and the Red Stocking’s hatred of Wonder Woman). And she then paints post-Roe feminism as a process of in-fighting, with people trying to out-radicalize each other.

At the same time, I think her heart wasn’t really in this: the real story is over, and she seems to be looking for a quick rhetorical punch. As a historian, she’s just not that invested in her New Yorker claim that Wonder Woman is “the missing link” (ha!) chaining the suffrage movement to “the troubled place of feminism a century later.”

6. A telling moment: Lepore tell us that historians have tended to use the “wave” metaphor to imply that nothing much happened in feminism between the 20s and the late 60s. Here is the totality of that argument: “In between, the thinking goes, the waters were still.” The note to this passage, oddly, only refers to writers who have challenged the “wave” metaphor — which Lepore then does herself later, saying we should call it a river. Oddly enough, it is Lepore who then makes the claim that nothing much has happened in feminism between 1973 and today, characterizing the years as a series of generation of women, all eating their own mothers.

7. The book is the most exciting and well-researched piece of scholarship related to comics I have ever read. At the same time, I hesitate to call it “comics scholarship,” per se. And this isn’t simply a matter of guarding the field’s borders, keeping it safe from poachers. THE SECRET HISTORY OF WONDER WOMAN, in the end, just doesn’t seem particularly interested in Wonder Woman comics, Wonder Woman stories, or Wonder Woman art — except as “telling” and glittering superficialities of a much more interesting biographical and historical tale.

She does not spend much time looking at Wonder Woman as an artistic creation, giving shape to particular concepts or exploring certain obsessions. Rather, the links of the comics to history emerge in the book as series of equations, or even one-way vectors: Hugo Münsterberg => Dr Psycho; Appellate Judge Walter McCoy => the stammering Judge Friendly from the comic strip; Progressive Era fights and imagery => Wonder Woman’s fights and imagery; Marston later behavioral troubles with his children => Wonder Woman’s later stories with kids named Don and Olive.

Moreover, these claims are not so much supported as *revealed* — and very briefly revealed, in most cases — like when Lepore parenthetically discloses that Marston had written a story about Wonder Woman and rabbits after talking for a page or so about the pets at Cherry Orchard. Large passages of the book take this form: tell an exciting and detailed story about Marston or Sanger, then close the chapter or section by saying, in essence, “this happen in Wonder Woman too.”

8. This isn’t to say that the book doesn’t change the way we look at Wonder Woman. The comic, after one is done with Lepore, seems to just vibrate with historical energy: the last, unexpected explosion of Progressive Era feminism. But it is not really a book about Wonder Woman; it is a book about Marston and the world of women in which — and out of which — he made his fame.

Marston comes across, in the end, as a classic American charlatan and genius — and a genius due in no small part to his charlatanism. He is a huckster, a relentless self-promoter, an almost unending failure, and even (in my opinion) a misogynist. His heart, politically, is in the right place, but his ego and his loins are often someplace else.

9. Perhaps this makes the biggest secret of Wonder Woman the fact that she ended up existing in a such a potent and coherent form at all, coming as she did from the mind of a man who (after reading Lepore’s account) seems to have been a mass of contradictions, opportunism, and outright absurdity.

Luckily, the book seems to say, the women in his life and his world were strong enough, politically and philosophically, to counteract Marston’s personal weaknesses.

The book’s biggest secret: Women and feminism — not Marston — created Wonder Woman.

That’s a great comment. I’d quibble at a couple of points…mostly I don’t think Lepore thinks of Marston as a genius, or presents him as a genius. There’s nothing in the book that suggests that she thinks WW has any particular aesthetic or intellectual merit. I would say your last point — that she sees feminism as creating Wonder Woman — is true; she’s excited about Wonder Woman because she sees it as being created not by Marston, but by the milieu of the time. I don’t find that really very convincing, except in the trivial sense (everything is a product of its time and intellectual milieu; the Elizabethan era created Shakespeare’s plays, modernism made Ulysses, etc.) Focusing on the milieu ends up downplaying how odd WW is…and it also oddly means that Wonder Woman becomes about the milieu Lepore sees, rather than about the milieu Marston saw. As a result, it misses some of the ways that Marston is arguably more modern than Lepore — particularly in his belief that queerness, sexuality, and alternate sexualities are central to feminism.

I also think that when refusing to engage with theory seems like especially a problem when you’re writing about someone like Marston, who I think was actually a feminist and queer theorist. It’s like writing a biography of Foucault and spending more time on his family connections than his ideas. Though, again, I don’t think Lepore feels like Marston’s ideas have any merit or interest, so that’s presumably why she largely ignores them.

I think you like the book more than I do, Peter, but I really appreciate your thoughts. I’d say it’s definitely comics scholarship — just, as you say, comics scholarship not very interested in comics.

Oh…re the idea that Marston was ridiculous and misogynist…I’d say that there’s truth to both of that, but I don’t know that it means that none of his ideas can have any merit except as an involuntary effusion of the milieu in which he (accidentally?) found himself. It’s not like he’s the only feminist thinker who ever had intellectual or political weaknesses. Susan B. Anthony’s racism and Jill Lepore’s own discomfort with queerness spring to mind as a couple of examples immediately to hand — not to mention feminism’s long time struggles with trans issues (which I think Marston actually negotiates quite well, as I talk about in my book.) Lepore does make Marston look ridiculous and problematic, which he was. But she doesn’t really manage at all to talk about the ways in which he was visionary or inspired. I think that’s a loss.

Marston was really racist too, of course, which Lepore points out.

Okay, I’ll stop commenting!

Agh! Keep having more to say. Oh well, my blog and all that.

Your point that Lepore is interested in politics, and therefore not in queer history, is telling — because of course queer history is every bit as political as feminist history. Focusing on Wonder Woman could be a way to make that point,and to argue that queer and feminist history are in many respects the same history. Marston saw them that way, I think. Lepore doesn’t — but that’s not because she’s interested in political history, but because she’s interested in a particular political history, one that excludes the Marston family’s sexuality as political. I think the fact that you come away thinking that Marston’s loins led him to misogyny (which is partly what I see you as saying) is what Lepore thinks too — and of course that mirrors the way that the feminist movement has sometimes policed, or rejected, alternate sexualities and gender identities (BDSM, polyamory, sometimes lesbianism, transsexuality) as politically retrograde.

I’ve considered using Lepore’s New Yorker article in my superheroes course next term, on the assumption that it is a sort of precis of the book, i.e. that the article previews claims that the whole book substantiates and deepens (I haven’t yet read the book, obviously). Doing the whole book might be prohibitive in terms of both time and cost (though I note a softcover ed. under $20). But I’ve found that Marston-era WW is worth a lot of time and is highly teachable (which will surprise no one following this thread, I bet!).

Other scholarly interventions I’m thinking about sharing with my students include Molly Rhodes, Geoffrey Bunn, Lillian Robinson, Ben Saunders, and of course Noah.

Primary text: DC’s Wonder Woman Chronicles V1 trade.

Q: Given 2 to 3 weeks to discuss Wonder Woman and Marston in the context of a 14-week course that bids to survey the entire history of the comic book superhero (gulp!), how might you all proceed? I’ve done this once before, in 2010, before Noah, Saunders, or Lepore had published on WW; now the question is even more challenging!

Well, obviously you need to use my book. It should be a standard in all curricula!

Seriously, though, it probably depends on what you want to do? As Peter says, Lepore’s book doesn’t really engage with the comics pretty much at all. If you want students to learn about studying comics as an art form, or even a social text, I wouldn’t say she’s a very good source. If you’re more interested in the historical context in which Wonder Woman in particular was created, then she’d definitely be the best source available.

I guess if it were me the New Yorker article would be tempting as away to give historical context if you were going to spend a day on Marston/Peter. Have you seen the roundtable we did on the last issue of Marston/Peter?

https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2012/04/bound-to-end-wonder-woman-28-index-and-introduction/

Sharon Marcus’ essay and Charles Reece’s essays I think are especially useful.

I think Bunn is good, but largely superseded at this point by Lepore…and I think I’d probably take Ben Saunders’ over Lillian Robinson at this point. Tim Hanley’s discussion in Wonder Woman: Unbound of his quantitative evaluation of the amount of bondage in Marston/Peter seems like it would be pretty entertaining for undergrads.

Obviously I’d like folks to buy my book for their classes, though it’s hard to look at it objectively in terms of a request like this. Peter’s read the ms and could maybe tell you better than I (though I think(?) you’ve read it as well, yes?)

Whoa…didn’t realize you were doing 2 to 3 weeks on Marston! You should definitely assign my book then!

I guess the advantage of mine would be that I actually talk about specific stories in WW at some length (including the origin in volume 1); I don’t know that there’s a ton else out there in terms of close readings of particular comics (as opposed to more generalized discussions of the series as a whole.)

Noah, well I think you and I can at least agree that people who leave really long comments — or series of long comments — clearly have something wrong with them. Stop me before I comment again!

Actually, I found almost nothing in your reactions with which to disagree, at least not in any strong way. I have, as you put it, quibbles — which sometimes means that I actually have quibbles with my own original way of phrasing things.

Take “genius,” for example. I agree, Lepore doesn’t see much of interest in Marston’s particular set of ideas or creative abilities. No artistic genius there. But as I tried to put it, there does seem to be a certain admirable genius in what I call his charlatanism, his endless juggling act of self-promotion. Marston emerges as an archetypically American sort of confidence man. He is huckster, opportunist, failure, and eternal optimist, who in the process of relentlessly reinventing himself, improbably creates something beautiful and politically potent.

Which is perhaps why Wonder Woman can emerge, for Lepore, as the “product of her times” so fully: because in the book, Marston does not seem to have the intellectual or moral wherewithal and commitments needed to do “real” creating. In spite of all the time the book spends with Marston, he sometimes emerges as simply a confluence of ideas and actions that actually originate in strong women of his past and present. It’s not that Lepore argues that Marston “stole” these ideas or hogged the credit — although she sometimes comes close — but you rarely get a vision of Marston as doing much more than collecting the iconography, images, stories, and moral purpose around him into a coherent form — and then pushing, pushing, pushing it into the public view.

So yes, you’re right. Lepore recasts Wonder Woman as a power political document — a reflection and secondhand embodiment of women’s political lives — by, unexpectedly, downplaying Marston as a creative force and all but ignoring what makes Wonder Woman,, the comic book, odd and idiosyncratic. Nonetheless, the story of how all these women and forces and icons comes together, through and with Marston, makes the very existence of this superheroine seem that much more miraculous.

One last point of agreement regarding queer history vs. political history. I do think there is no division here, at least in a strong sense. But for Lepore — and I don’t think this is a misuse of the term — “politics” are about what happens in public, in the polis. Not really about what happens in private, even if these privacies are structure by political forces. Lepore tells a story of political, public women (and men), carrying on political, public forms of action and resistance — as well as public self-promotion, self-invention, etc. That may not be a distinction worth making, but it’s one the book banks on. (The book, for all its talk of secrets, actually seems fairly clean of discussion of private lives or speculations about personal motives of all sorts.)

So is The Secret LHsitory comics scholarship? Here I show my own bias, tending to think of comics-studies, as such, remain and ought to remain in the ambit of literary studies, textual theory, and art criticism. There’s just an important difference between how a historian talks about art and the way a literary or art critic talks about art. For me, that difference comes down to issues of form or the specificity of the medium, no matter how engaged you are with content and context. That is, it matters that the thing you are discussing is a comic, and not some other kind of document.

For Lepore, as a historian talking about comics, this doesn’t matter. Indeed, she seems to endorse the story, repeated at least three times in the book, that really all you need to know about Wonder Woman can be found in Sanger’s Woman and the New Race. The rest is just formal rearrangement.

And that’s where the difference makes a difference. To have access to Marston’s scripts and not spend more time analyzing how this writer gave shape to these ideas, transforming or twisting them, seems almost unthinkable. To only look at the Wonder Woman stories that match up with aspects of a historical precedent feels like a lost opportunity. To talk about the art for, at most, five pages in total seems like a waste. And taken all together, these make The Secret History of Wonder Woman into a riveting and powerful history — an awe-inspiring tale and art of research and writing — but not into a piece of comics scholarship.

And it shows why Noah’s book will stand as the perfect and necessary supplement to Lepore’s archive.

Well, jeez, how am I supposed to disagree with that?

Jiu-jitsu-ed! :)

I will say, given feminism’s emphasis on how the personal is political, it’s odd for a feminist history to see politics in such public terms — which I’d agree Lepore’s book does for the most part.

Well, I finally found something that Noah and I can agree on, that Lepore’s book isn’t a “history of Wonder Woman.”

Further, though I’ll probably disagree with Noah’s interpretations of Wonder Woman stories, he will certainly analyze them, rather than passing over them as epiphenomena.

I notice that Noah’s biggest problems with the book are far from being my own, though.

http://arche-arc.blogspot.com/2015/03/everything-you-wanted-to-know-about.html

Yeah…I can’t say I really care whether she was fair to Robert Kanigher. Kanigher was pretty sexist, as well as just not paying much attention and being a bad writer. He probably didn’t write the worst Wonder Woman comics ever, but it wasn’t through lack of trying.

Hey, wait a minute, pal. Kanigher introduced Egg Fu in the pages of WW. This is a seminal moment in 20th century American culture and cannot lightly be dismissed!