This is one of those posts I wrote for another site, but then it didn’t work out. So here it is; slightly off-brand for HU, but so it goes.

___________________

Anonymity makes the Internet ugly. This is common-sense online wisdom, and there’s research to back it up. A 2014 article by Arthur D. Santana examining newspaper comment threads found that “Non-anonymous commenters were nearly three times as likely to remain civil in their comments as those who were anonymous.” Non-anonymous forums significantly reduced abusive comments, or, as Santana put it, “there is a dramatic improvement in the level of civility in online conversations when anonymity is removed.” Anonymity makes people meaner; it creates less civil, more toxic communities.

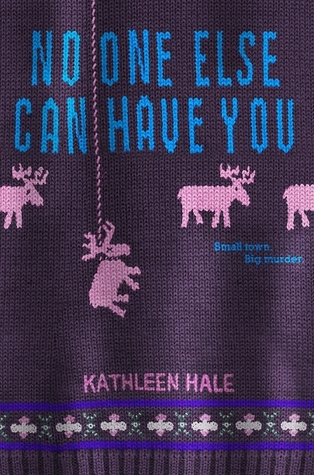

This is the context in which Kathleen Hale’s recent article about an anonymous reviewer was published at The Guardian. Hale is a writer and the author of the novel No One Else Can Have You. Her article is about one of the novel’s critics, an anonymous online reviewer who went under the alias of Blythe Harris. Harris, Hale claims, was notorious among authors on the Goodreads book discussion website for her negativity and for abuse. Hale cites one instance in which Harris and her followers targeted a supposedly 14-year old reviewer, swamping her with abuse and profanity (whether the 14-year-old was really 14 is open to question.) Hale’s lengthy essay goes on to describe how Hale tracked Harris down and unmasked her.

Hale acknowledges that her obsession with Harris’ reviews and criticism wasn’t healthy; in the first sentence of the essay she characterizes herself as a “charmless lunatic.” But she also seems proud of her success as a “catfisher.” In online parlance, a “catfish” is someone who creates a fake identity online in order to deceive others, especially potential romantic partners. Harris, here, is the anonymous catfish — she’s a deceptive troll, and Hale reels her in and brings her down. Hale admits to being obsessive and pitiful, but the narrative presents her as a bit heroic too. She’s taking a stand for bullied authors and against the uncivil, anonymous hordes.

The problem is that, reading the essay with just a little bit of skepticism, Hale doesn’t come off as the good guy in this interaction. She presents her “lunatic” behavior as funny, obsessive, quirky, and sad — “Over the course of an admittedly privileged life,” she says, “I consider my visit to [Bythe’s] as a sort of personal rock bottom.”

But what she doesn’t say is that, if you identify with Harris for a moment, the stalking behavior is terrifying. Hale uses her influence as an author to get Harris’ personal information, including her address and work phone. She shows up at her house. She calls her workplace multiple times. And then, she writes an article in an international venue in which she shames and vilifies the woman she has stalked. The Guardian says that some of the names in the piece were changed— but Blythe’s online name is not changed, and her real name appears to have been used as well (at the least, there is no clear statement that the name was changed.) Even just printing the name Blythe uses online is problematic; attacking someone in a mainstream forum can send angry readers swooping down on their social media accounts in droves. The article itself is effectively an extension of a campaign of harassment aimed at someone whose main sin was that she didn’t like Hale’s book and didn’t use her real name online.

Again, there is evidence that anonymity is associated with incivility and bad behavior. But anonymity doesn’t cause incivility, or, at least, it’s not the sole cause. Santana’s report noted that 30% of non-anonymous comments on the news stories they surveyed were uncivil. Anonymous users are responsible for a lot of abuse online, but by no means for all of it. Personally, some of the most memorably unpleasant interactions I’ve had on the Internet have been with people using their real names — in some cases, with established journalists.

More, there are some good reasons why a writer online might want to be anonymous. As Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens wrote, “The decision in favor of anonymity may be motivated by fear of economic or official retaliation, by concern about social ostracism, or merely by a desire to preserve as much of one’s privacy as possible.” To provide just one example, there are incidents of teachers being fired for expressing controversial opinions online; any teacher, therefore, has good reason to hide his or her identity in online forums. For that matter, as author Bree Bridges commented on twitter ,” “Why would a reviewer EVER use a fake name?” implored the author currently stalking the hell out of one. “I can’t think of one reason.”” Hale’s article demonstrates exactly why a reviewer might want to use a pseudonym. If you can avoid it, you don’t want an obsessive stalker like Hale to know who you are or where you live.

Hale’s article raises the disturbing possibility that anonymity may lead to less civility — and that decrying anonymity may also lead to less civility. Some people, clearly, feel empowered by anonymity to hurl abuse and threats, as the ongoing death threats against women in the gaming industry demonstrate. But at the same time, the association of trolling with anonymity, and the use of terms like “catfishing” makes people like Hale (and apparently her editors at the Guardian) feel like they are entitled to stalk and shame people they disagree with online. Decrying anonymous trolling, and the association of anonymity with deception and bad actors, can be used to justify further harassment and abuse aimed at the supposed bullies.

Hale’s essay unleashed a firestorm of criticism from book writers and bloggers (some examples are here and here. A number of blogs organized a blackout on reviews of new releases in an effort to bring attention to the fear many reviewers feel that they might be targeted by authors. Hopefully Guardian Books and other publications are paying attention. Just because a writer is anonymous doesn’t mean that it’s okay to stalk, harass, and humiliate them. Even though anonymity is often used for incivility online, a pseudonym, in itself, doesn’t make you a legitimate target.