Just under a year ago, I started a new gig that I was cautiously excited about: creating editorial comics for the Week in Review section of The New York Times. David Rees was going to write them and I was going to draw them. This seemed like an ideal partnership; David (creator of the satiric comic Get Your War On) has a great skill for walking the fine line between irony and sincerity, and is extremely funny as well. We both wanted to try to do new things with the political strip format, and bring metahumor to the Times.

Already, though, things were not as we’d been promised. The Times had approached David and then myself in April of 2013. After approving us, they told us their master plan: Brian McFadden, the resident comic artist, would be replaced by myself and David alternating with Lisa Hanawalt. This would be a part of the exciting revitalization of the Week in Review section. To that end, they told us to wait while their redesign proceeded.

By September, the redesign seemed to be finished; but the editor in charge decided that something as exciting as this new comic rotation couldn’t be unveiled in a dull month like September. Better to wait until… January! when it could be announced to the world with the appropriate fanfare and excitement.

So we waited seven months in all. And on January 20th, David & I created our first strip for the Times… which was printed with no fanfare or announcement or anything; we were simply dumped into an alternating slot with McFadden, because by then Lisa was simply too busy (drawing Bojack Horseman). The brilliant strategy of waiting all that time had backfired, because in fact it was pointlessly stupid.

Then there was the money. The New York Times– get this- refused to come up from the fee for one artist, which we were to split. We finally got them to come up a little, but only a little. These strips are done in a very short time period- basically between Wednesday night and Friday morning, and I stayed up all night for a couple fo them. We were going to be making very little money, but still, it was an opportunity to do good work, maybe make some statements on serious issues and have them be seen by people. And the Times still stands for something in peoples’s minds, some kind of editorial quality.

Of course, it didn’t work out at all; their nitpicking, antiquated style of editing got more oppressive until they were killing entire strips. And it’s quite clear they were refusing to print them because they didn’t understand them. It was like being edited by hobbits.

The first few went through fairly smoothly; David pays close attention to the news, and the art director mentioned approvingly that she was glad he was tackling issues that the paper wasn’t covering otherwise. The one thing that bothered me was: we would present the script, the editors would make corrections, I’d create a finish. Then, after I’d handed it in, I’d get back a complete different set of corrections, mostly concerned with their antiquated style guide. The Times puts periods in “IRS,” for instance, even though the IRS themselves do not. They also changed the wording of Donald Rumsfeld’s letter to the IRS when we quoted it directly; that seemed wrong to me. And that they couldn’t do all the corrections at once, before I’d done the work, felt to me like laziness and a lack of coordination which ended with me doing unnecessary work at the last minute.

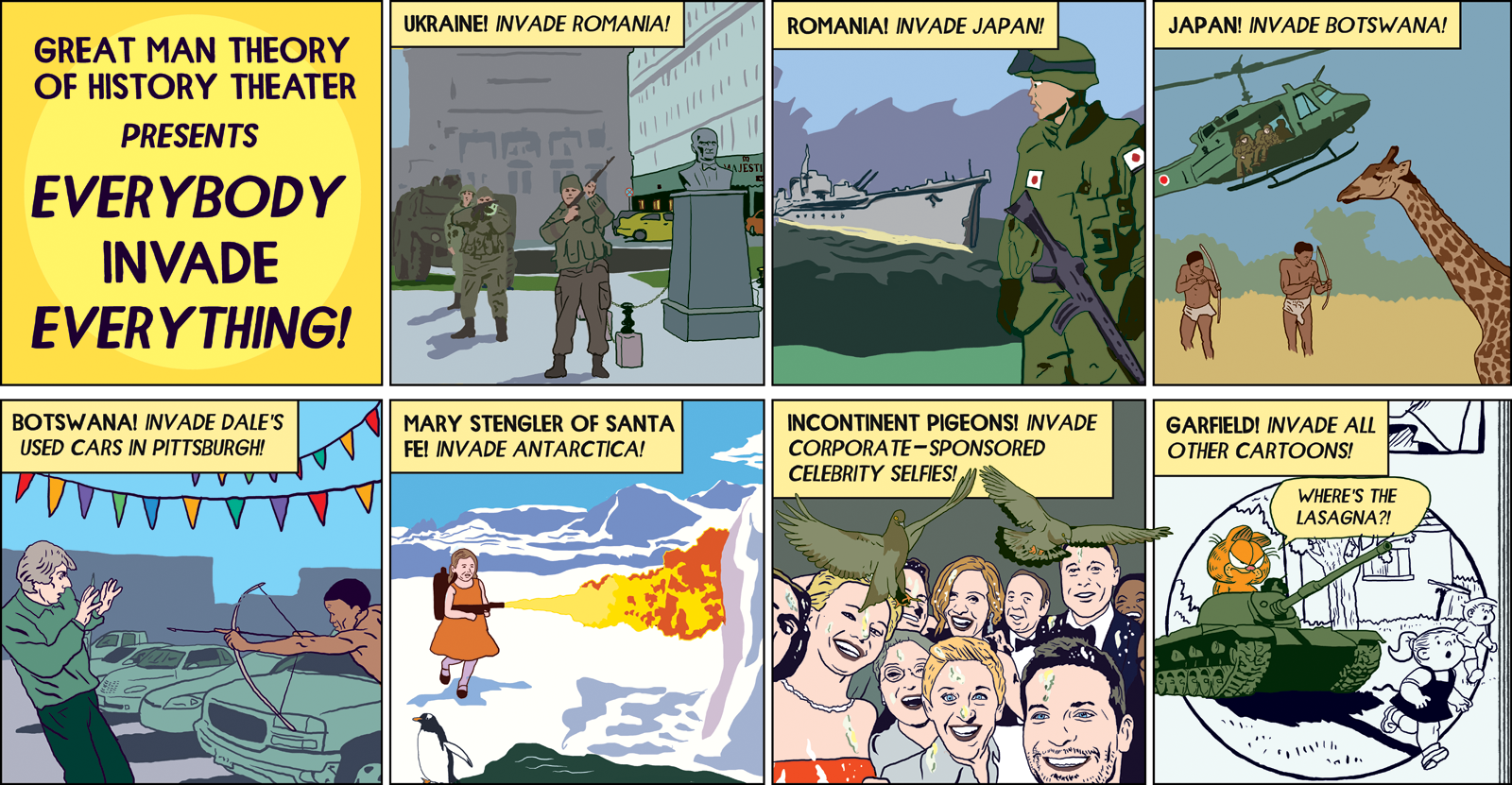

They did start reading the script more closely, though, after our fifth strip. The script mentioned the cartoon character Garfield and tribesmen in native costume in Botswana, so I was less than sympathetic when they were surprised when the art was turned in. “We have to check with our lawyers if we can use Garfield,” the AD said, and “the tribesmen in Botswana are making people uncomfortable.” Soon came the word that the lawyer had said Garfield was okay (luckily they had asked one who understood the first amendment). I hope they would also drop the tribesmen issue, but no. They insisted I make it a different country, and have them fully clothed. I thought about it for maybe five seconds, and then I said something I’d learned to say after a lot of bad experiences with illustrations and comics that turned out mediocre because of meddling editors who thought they were smarter at what I do then I am. I said “I’m not comfortable with that.” And they… backed down. Okay, we’ll print it the way it is.

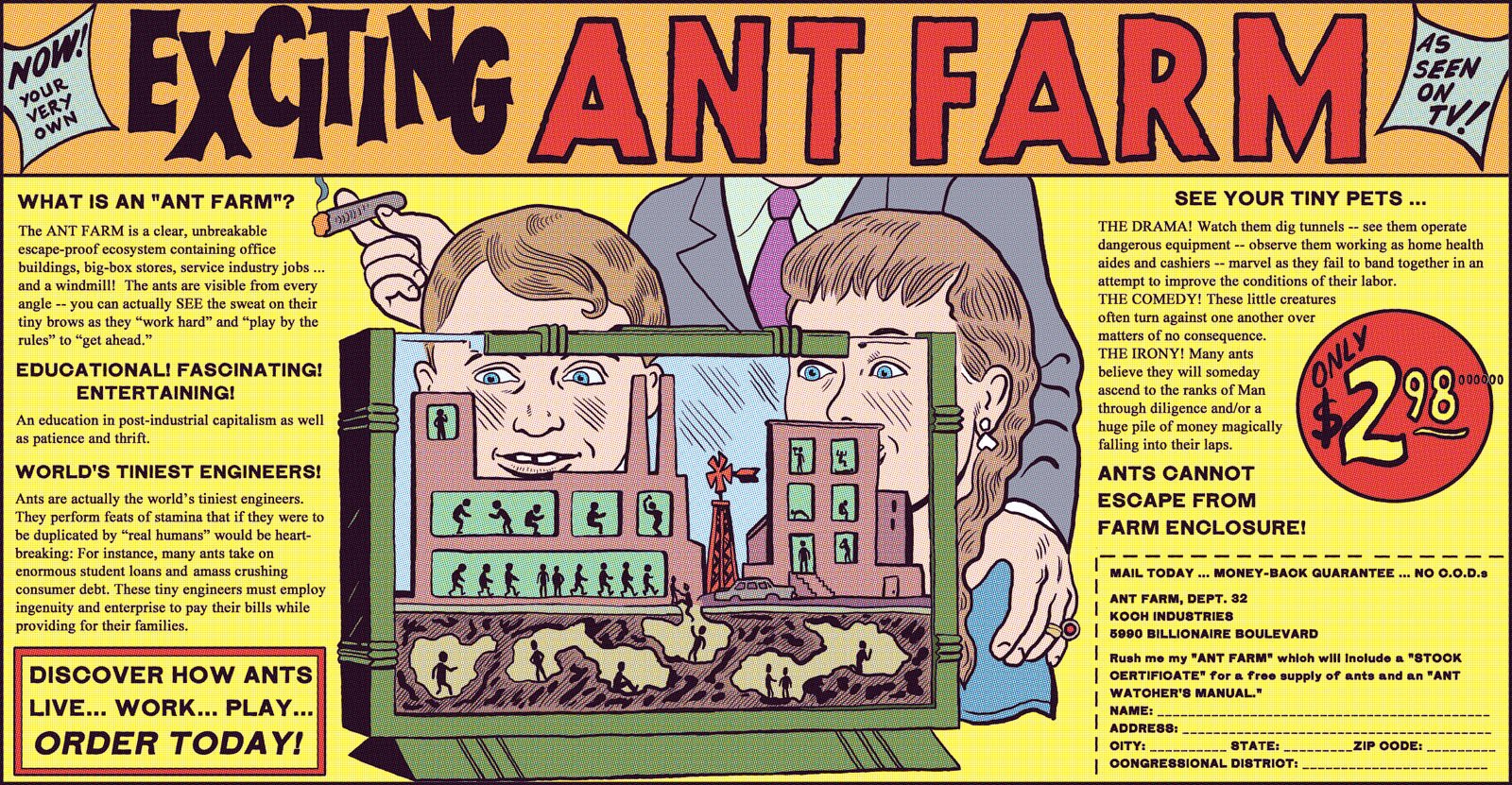

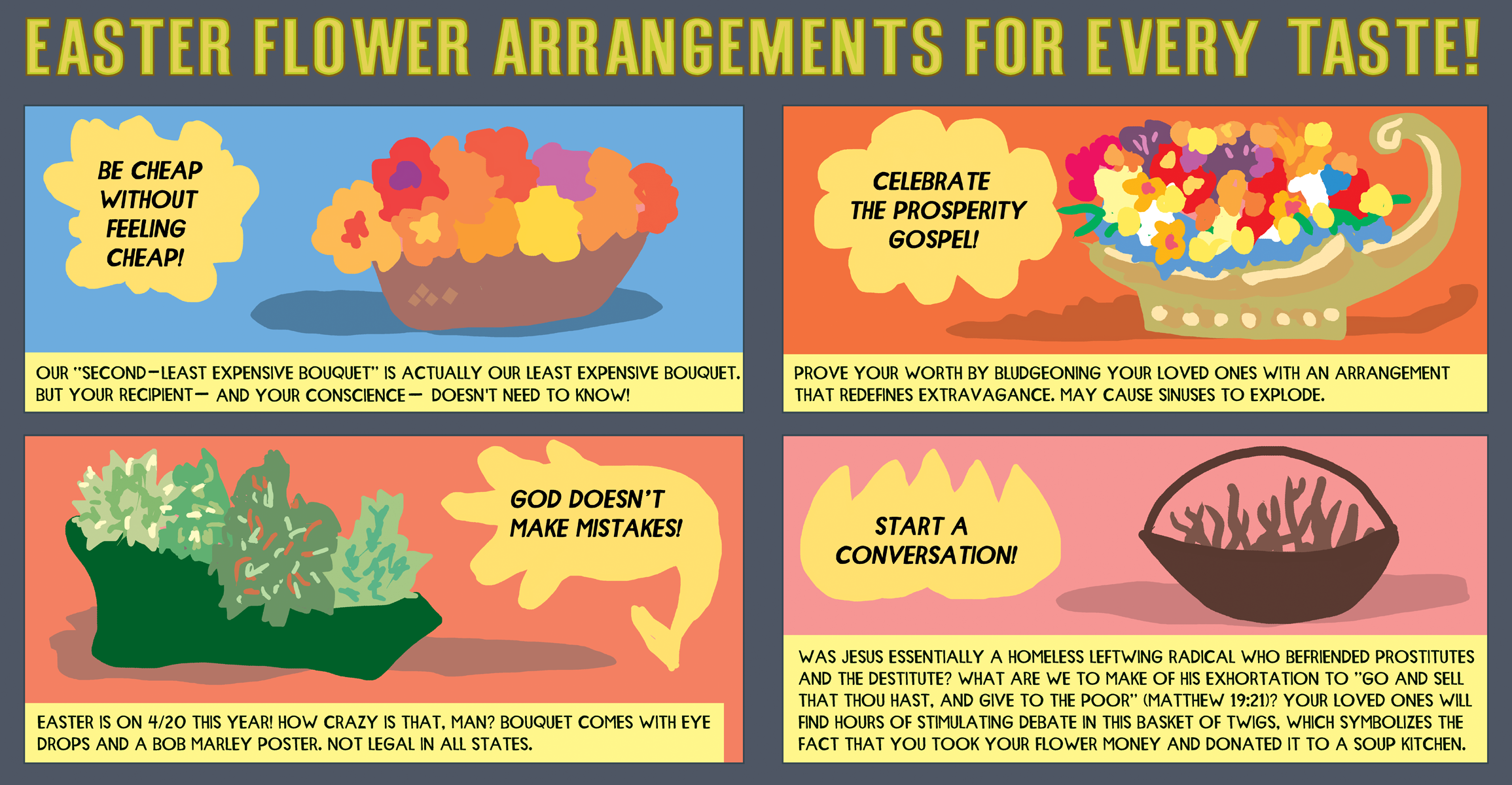

I thought we’d won a small, but important victory. Of course, I was kidding myself. Two strips went by and then it was Easter; David wrote a script parodying floral bouquet ads. It showed several extravagant bouquets before showing a basket with twigs in it, suggesting that maybe the real spirit of Jesus would be served by saving the money spent on bouquets and giving it to a homeless shelter. It was David at his best: sharp, moral, funny & brilliant. (I’ve done a rough of it to show you here).

They hated it. “The editor is asking why are we making fun of religion” came the reply. I couldn’t believe this, and still can’t; it’s the response of someone who can’t read. David was doing the opposite of making fun of religion; he was in fact underlining one of its central tenets, the concept of charity. He felt really strongly about it, and even managed to talk with one fo the editors to make his case. But no amount of arguing would dissuade them. We had to come up with another strip in a hurry.

A sketched-out version of the unpublished strip.

The next strip went through with no difficulty, and then David wrote a strip about male bullying online. That week, the hashtag #yesallwomen had taken over Twitter, following a misogynist’s killing spree in California. The reaction to this was a torrent of abuse from men and boys towards women- and this was before Gamergate, which really took it to another level. As always, David’s strip on the subject was right on. His script had a pair of baby-men (wearing diapers) talking about trolling and threatening women online. I was excited, because I knew this was one that would attract attention, and make a point that deserved to be made. Incredibly, the Times wouldn’t touch it. “So I floated this by the editors, and they all feel that this news story is just too sensitive to be prodded at in a humorous way,” was the way the substitute AD put it.

This was when I had had enough. Too sensitive to be prodded at in a humorous way? Why had they hired us? What did they think we were supposed to be doing? David was busy at that point doing his TV series for National Geographic, so I told the AD that I was not happy with the Times‘s behavior, that we would not be giving them a substitute strip for that week, and then I created a rough version of the strip from David’s script and put it online, with a full explanation of how the Times wouldn’t print it. It got more attention than anything else we’d done for them.

A sketched-out version of the unpublished strip.

We did one more strip after that and then, big surprise, they fired us. But once the Times had made it clear that we were not allowed to offend anyone, or handle any but the safest material, it was all over for us anyway. For me, as a cartoonist, it was another depressing reminder of how bad things have gotten in the print world for people who do what I do. David had a TV show. Lisa had a TV show. I was working in print and I felt like a real loser for it.

I couldn’t help but think of all this again this week as the images from Paris appeared online. Cartoonists had given their lives for the freedom of speech their work represented. It still means something over there.

_______

________

For all HU posts on

This entry was posted in Blog, Featured, Satire and Charlie Hebdo Roundtable, Top Featured and tagged censorship, David Rees, editorial cartoons, Get Your War On, Michael Kupperman, New York Times, NYT, Satire and Charlie Hebdo Roundtable by Michael Kupperman. Bookmark the permalink.

NYT has always been really anally retentive. They probably had the vapors at the very THOUGHT of running comics no matter what the content. Je suis Charlie. And so are you, Mr Kupperman.

It’s the insistence that the text conform to NYT style that gets me. That just seems pointless and insane. It’s a cartoon; no one expects it to be stylistically the same as the text. Why waste everyone’s time like that?

I’m glad you ran that man-baby strip online after the Times rejected it. It’s funny and spot-on.

Most pubs I’ve worked for in the last 30 years have been the same as regards political work … they talk big, pay nothing and without exception, make certain your idea is completely clichéd to death before it’s allowed to grace their sloppily designed, haphazardly proofread pages.

edited by hobbits … perfect!

Great piece! when places like the New York Times, CNN, Public Radio – venerable long standing institutions – say they want to “take risks” they don’t really mean it or they only want to do it VERY gradually and subtly.

Or maybe their issue with the tribesmen was that the only non-white people in the strip were presented and dressed in a ‘traditional’ way that doesn’t reflect life in those countries nowadays. Maybe you were using stereotyping and poor research to make a laboured, race-based point.

This is no surprise to most people who have had any experience there.

I was more offended by the way you dressed the salesman from Dales Used Cars. Every enlightened person knows that Dale forbids them to wear green.

I think the excessive nit-picking of small details is the point here, and not understanding the underlying points of the comics themselves or an alternate method of creating an opinion piece.

P.S* You need another TV show

*Please run this by The Style Council to see if this is the proper use of PS.

Yeah; at least for me, I could see an editor flagging the Botswana panels in the script and saying, this seems to maybe be saying something you might not want to say. Are you sure this is what you want?

One problem with arbitrary nit-picking is that actual concerns which it might be worthwhile to address get drowned out. Editors can be helpful if they have a baseline level of respect for what you’re doing, and are trying to help you communicate better, rather than primarily trying to cover their own asses.

For as long as I’ve been politically aware, I’ve hated on political cartoons, as I’ve thought them trite, easy, and sort of dumb. After reading your essay, I’m sad to see that I was right, and that this dullness is an actual decision made by newspapers.

Charlie Hedbo “got away” with their brand of politicking by having their own paper. I’m not sure Le Monde, for instance, would be different than the NYT.

I’m not sure we should be praising the bravery of Charlie Hedbo as loudly as we have been, however. Every example of their work that I have seen has been an attack on an immigrant community which France is debating whether or not to allow into total citizenship. It’s a bit like saying nice things about Storm Front. Maybe Charlie Hedbo spends 90% of their anticlerical energy going after the Catholic Church, though. That’s an institution with real power in France, and attacking them would make most French people annoyed, at least.

I took the Botswana tribesmen, along with the rest of the comic, to be a jab at “great man history,” which typically emphasizes the actions of a few, mostly white men and is generally understood to be an antiquated form of historical inquiry. That’s just me though!

@Punning Pudit

I just googled Charlie Hebo anti-catholic and got Pictures of God Father getting fucked by Jesus and the Holy Spirit sticking in Jesus ass, Baby Jesus boasting out of Marys vagina, Pope Francis dressed s a brazilan Sambadancer, Cardinals fucking each other and Pope Benedic making out with a Swiss Guardist.

Yeah; Charlie Hebdo’s political position in France is quite complex, and not well-summed up by comparisons to the U.S. situation. They were left wing, for example. This is a good discussion of their work in the French context.

I understand that it’s obviously somewhat relevant, but I don’t want this thread to become a debate about Charlie Hebdo, if we can help it. So, please try to stay on topic all, if you would. Thanks.

There’s something about the total lack of humility in this piece that rubs me the wrong way. I was particularly struck by how you thought about your editor’s comments on your depiction of Africa for “maybe five seconds” for dismissing it out of hand. Is that artistic integrity? Or could it be something else?

At the risk of sounding rude–though this is more a critique of Rees’ words than your art–that Easter flower comic didn’t strike me as all that sharp, funny, or brilliant. Nor is the man baby comic, and I say that as someone who fully agrees with its sentiment. So I guess my question after reading this is were you really sacked for being too offensive? Or is there a possibility that you were sacked because these comics aren’t all that great?

I don’t want to minimize the indisputable fact that you were mistreated by the NYT. For what it’s worth, I really relate to your frustrations with the editing process. In my experience, the bigger the publication, the more heavy-handed the editorial practices. But I fail to see what your story has to do with freedom of speech. Freedom of speech, as I understand it, means the New York Times can print whatever it wants. For whatever reason, it didn’t want to print you.

“’The editor is asking why are we making fun of religion’ came the reply.”

“‘So I floated this by the editors, and they all feel that this news story is just too sensitive to be prodded at in a humorous way,’ was the way the substitute AD put it.”

Kupperman’s story asn’t about censorship, it was about the refusal of editors to think visually when doing visual stories. Drawing a story is very different from writing a story but most editors insist that you draw as literally as possible, no matter how dull and clichéd it looks. Frankly, I’m amazed that MK got away with what he did.

Kim, I get the point about free speech being just government censorship. However, at some point, that can turn into a blanket defense of the market; whatever a corporation decides to do is right, and there’s no moral ground for criticizing.

It seems pretty clear that the Times censored a number of strips for content reasons (they said as much.) The Times is a major platform, and a driver of coverage in the U.S.; if they’re unwilling to criticize religion, I think that does in fact have free speech implications.

Honestly, Noah, do you not think that’s overstating a little? The NYT didn’t suppress reportage on some scandal that might offend Christian sensibilities. It made an ambiguous comment about a cartoon: “The editor is asking why are we making fun of religion.” Is that really evidence that the NYT is unwilling to criticize religion? I just googled the Week in Review (I wasn’t sure if it was part of the Sunday magazine or what), and Bill Keller says its mission is to bridge news and opinion by helping readers see things in unexpected ways. Does the Easter comic do that? Is it timely? Insightful? Tied to current events in any meaningful way? Were florists making bank off shallow Christians in 2014? Are Easter bouquets even a thing outside of, like, nursing homes? As an editor at the NYT Week in Review, might you wonder why you were getting some half-baked Easter commentary from the guy who’s known for Get Your War On?

I dunno, all I know of these conversations is what I see here. Maybe those editors really are cowards, but that was not my takeaway from this piece. What I see is evidence of a bad relationship between editors/artists and an ill fit between content/publication. I don’t know Kupperman’s work at all, but I do know Rees’ stuff (a bit), and I can see how the comics in this piece aren’t topical in the same way as his most famous work. If promises of creative autonomy were made, that’s one thing, but artists are generally expected to tailor their work to the publication, not vice versa. Some of that has to do with content and tone; Tim Kreider’s opinion pieces for the NYT are different than the ones he writes for lad mags. Other stuff is more petty like the stylistic examples Kupperman mentions above; the New Yorker is not going to print hyphens for god or Murakami.

Well…I mean the comic is not making fun of religion. So asking why they’re making fun of religion does suggest an over-sensitivity to me.

You should check out Michael’s Tales Designed to Thrizzle. I wrote about it here.

Sorry, I have to agree with Kim O’Connor above, these pieces just aren’t that great. I’ve loved Rees since “My New Fighting Technique…” But the bouquet one in particular just seems like warmed-over “This Modern World.”

Noah, the prosperity gospel is a real (though ridiculous) religious movement, and it seems clear it is being made fun of above. Rhetorically asking whether Jesus was a radical bum seems flippant, at the least, even if it can be justified. And, for some, the dinner traditions (including an unnecessary and often ugly floral arrangement) are an extension of their religious celebration of Easter. Those are fair things to poke at, but are you really pretending that isn’t what was going on?

Tavis, I don’t think it’s about the prosperity gospel. It’s about the secularization of the holiday.

Pingback: Kibble ‘n’ Bits 1/12/15: Micheal Kupperman vs the New York Times — The Beat

The use of the word “censorship” in this piece is restricted to promo blurbs and the tag section. It seems Noah, not Michael, is the one recklessly throwing the word around. Although Michael doesn’t help matters with the inappropriate comparison of his circumstances with those of murder victims in an actual instance of vigilante censorship.

The New York Times’ editors, as dunderheaded as they may have been, appear to have just been exercising their editorial prerogatives. Unless Michael and David were explicitly promised creative autonomy, the Times’ editors weren’t doing anything inappropriate. To say otherwise smacks of an overreaching sense of entitlement. One doesn’t have an unfettered right to a publisher’s platform simply because the publisher solicits one’s work.

If one finds oneself irreconcilably at odds with the publisher, then publish the work elsewhere. Which, as can be seen by the above article, is exactly what Michael did. No one’s stopping him.

Pingback: Comics A.M. | One party dropped from 'comic con' lawsuit - Robot 6 @ Comic Book ResourcesRobot 6 @ Comic Book Resources

You don’t have a right to a platform. But, again, if a major news organization restricts what it’s editorial writers can say for ideological reasons, that seems like it matters. (Thus “Manufacturing Consent”). And screwing with your artists is stupid and unpleasant; work conditions have a moral component, IMO. Paying the bills doesn’t mean you have an inalienable moral right to treat your employees as cogs, even if that is the current legal norm.

I mean…I know you’re a fan of Krugman’s writing, Robert, so you’re not a neoliberal. But how do you distinguish your position from Reganesque neoliberalism? If there’s no moral grounds to criticize the market for how it treats workers, or journalism for how it presents opinions, it seems like you end up in a place where the only basis for ethical standards is private property rights.

I think we need to allow for the possibility that these cartoons are not very good and the artists are kind of a pain in the ass.

It’s not clear that the quality of the cartoons one way or the other has much to do with anything; obviously folks may like or dislike different things. The NYT had seen their work and hired them on that basis.

I’m not exactly sure what the artists are supposed to have done that suggests they were difficult to deal with? They turned in work on time; they submitted scripts as asked. They were supposed to provide takes on the news, and they did that. They resented being jerked around and being told to bowdlerize their work, but it’s hard for me to see why they should be blamed for that.

Editors sometimes don’t know what they want and jerk people around. That’s not the fault of the people they’re jerking around.

I’m not at all surprised that the “New York Times” has a laundry list of taboo items and politically correct sensitivities.

The left only pays lip service to freedom of speech and freedom of the press. In fact, I believe they were the ones who created the label “hate speech,” which is now slapped on everything the offends almost anyone and anything.

For old farts like me, it’s pretty obvious that things are so bad now, satirical icons of the past like “National Lampoon” and Lenny Bruce would not at all be welcome today because they would cause the “that-makes-me-uncomfortable” crowd’s heads to explode.

Lenny Bruce had a lot of trouble at the time, so it’s not like there was once some sort of free speech utopia. National Lampoon’s completely inoffensive schtick would I’m sure be as acceptable today as ever.

What??!!!

Noah, have you actually READ National Lampoon, as opposed to just watching Chevy Chase movies?

They make Charlie Hebdo look like Holiday for Children,

Pingback: Editorial Comic on ‘Nightmare’ NY Times Experience: ‘Like Being Edited by Hobbits’ | World Entertainment | NigerianNation News

Pingback: Comics AM | One party dropped from ‘comic con’ lawsuit | comic con

Alex — The early- to mid-1070s issues of “National Lampoon” definitely took no prisoners.

That’s 1970s, I mean. There were no Middle Ages editions of the magazine that I know of. :)

Noah–

Neoliberal?

Saying that a publisher has a right not to publish or to insist on changes as a condition of publication is a far cry from favoring the privatization of the commons. Or opposition to worker and consumer safety standards. Or opposition to labor unions. Or opposition to progressive taxation. Or any number of other things near and dear to the neoliberal project.

Publishers make decisions about what to publish or not publish on ideological grounds all the time. Let’s say Katrina vanden Heuvel solicited work from a writer for The Nation. The writer then turns in a screed calling for the abolition of child labor laws. The writer got it in on time, too. Is it censorship if she refused to publish it? I don’t think so.

Publishers also negotiate or demand changes as a condition of publication all the time. I don’t think that’s censorship, either.

Censorship is generally understood as a government effort to suppress or punish the dissemination of material that’s considered objectionable. I’m certainly willing to extend the term to vigilante behavior with the same goals, such as the Charlie Hebdo murders. A publisher refusing to publish, or to demand revisions as a condition of publication, is not censorship. That conduct may be petty or stupid or objectionable for other reasons, but it is not censorship. Go down that road, and you’ll be calling Marvel and DC censors for not allowing a scriptwriter or cartoonist to do whatever he or she wants with their character properties.

It’s one thing to criticize the NYT editors as flighty, pusillanimous nitwits in serious need of reevaluating how they deal with contributors. Based on the article, it’s a criticism I’m on board with. But that’s not the same as saying they had an obligation to print Rees & Kupperman’s work as is, no questions asked.

Wonder if they saw their true selves as the Paris news emerged? Probably not.

Robert, when they say, we’re not going to print this because we don’t want to criticize religion — that seems like censorship to me. They’re certainly within their rights. But they’re also again a major news organization with a lot of influence on what gets discussed in the media and the country. I guess if you don’t want to call it censorship, you don’t have to, but it seems like there are ethical issues around free speech involved there.

I brought up neoliberalism because, as I said, that seems to be where you go if you take that logic far enough. Do newspapers have a public trust? Or are they just private property, with obligations to the shareholders and no one else? Neoliberalism says the second. I’m arguing that I think there are at least elements of public trust, which means there’s an issue of free speech here.

The Nation example doesn’t really seem like it applies, I don’t think. I can’t imagine that a pubication would green light a piece on “child-labor laws” without some discussion of the approach that the writer planned to take.

What this sounds most like to me is the piddly crap you deal with when you do education writing for tests and such, where there’s a fear of offending anyone. Testing companies obviously are private companies, and it’s a work for hire deal. But at the same time, widespread policing of what kids can and cannot see, or are and aren’t allowed to be exposed to, has ethical and political consequences. Maybe censorship isn’t the right word there. But I don’t think making it entirely a private matter is right either.

I don’t know why the NYT wants to start running ‘toons in the first place.

As a long-time reader of the Times, I find this back-story interesting and would be interested in hearing the Times’s version of events. I’ll add:

(1) I have enjoyed their addition of the weekly cartoon and recall some of them as being good stuff.

(2) I’ve found that many times — not sure whether Kupperman/Rees or McFadden or both — the published cartoons have struck me as extremely edgy for the Times, which, as Kupperman underscores, is stuffy.

(3) I appreciated the edginess — and have laughed out loud on the subway — and this strikes me as a testament to the Times that it provides such an audience to the voice. Referring back to my first point, I wonder whether others, feeling differently, led to any pushback.

(4) Even as an avid reader, I hadn’t noticed the Kupperman/Rees absence (though maybe if I think long and hard, I note not recalling much too-far-out-there stuff lately). Which is to say that Kupperman, in a fit of pride, may have walked away from a decent gig in which he ultimately was fungible. I wish him all the best, and will continue to read the Times.

I think the Times’ problem with the material was that it was comics. I can see editorial changes being requested for grammar or to to help a story make sense, but to sanitize the content is not something that should be done for an editorial page. It’s doubtful editors would ask for the same changes if the work were prose. I don’t see a professor asked to write their opinion on a feminist issue and then being told they might offend someone.

And if you’ve ever seen pre-1975 National Lampoon, it was the opposite of its legacy as an R-rated Mad that high school kids looked at for pictures of tits.

“… when they say, we’re not going to print this because we don’t want to criticize religion — that seems like censorship to me.”

The word pusillanimity seems most appropriate to me. I think even calling it cowardice gives it too much credit.

I agree this sort of thing is “piddly crap.” Which is why I object so strongly to calling it censorship. Censorship is anything but “piddly crap.” It’s a scary business. The Charlie Hebdo murders are one example; the obscenity prosecution of Mike Diana is another. Calling a stupid editorial conflict censorship seems akin to calling a blown football call an atrocity. It’s an overblown description, and it cheapens the term.

I agree there is occasionally a gray area between what is a private entity and a public trust when it comes to media. Radio stations and broadcast television channels are obvious examples, and I believe cable providers and even the MPAA qualify to a degree. In pre-Internet days, I would also include magazine and newspaper distributors.

However, I don’t think any print publication resides in that gray area. They don’t serve a significant public-safety need, and regardless of their level of influence, they don’t have the ability to control the public discourse. There was reason at one point in time to be concerned about monopolistic behavior, but the Internet has made that irrelevant. As such, publishers should be free to print (or not print) pretty much what they want.

So I will bow to the universal wisdom on National Lampoon; the only things I’ve seen it associated with have been thoroughly banal, but if folks say it was something else, I’ll believe you all.

I guess I think censorship can sometimes be brutal and horrible and big — but it can also sometimes be piddly shit that adds up.

New York Times is mainstream – appealing to mainstream people? So does satire appeal to the mainstream? Would they understand it? Do people like to be criticised, ridiculed – I mean they say the closer it hits the mark the greater is the noise created in the complaints. Maybe you could put it down to the NYT not being ready to handle your material. Perhaps a publication appealing to the slightly more anarchic reader would have been more able to handle the work.

It was the OPINION section. It wasn’t like a feature on a new Brooklyn artisan oatmeal restaurant or an apartment with a garden on the roof, it was in the pages of the paper that are supposed to have conflicting views and challenge perspectives, and in that context, you don’t worry about how people might be offended by something.

Apparently national lampoon is available for free on archive.org.

I loaded the December 1970 issue on a lark. There’ a romance comic parody starring Tricia Nixon that is funny but fairly tame. Later in the issue is a comic with “gags” about lynchings and monks setting themselves on fire. So… looks like they had a mixed style of humor. (I prefer the romance parody).

I tried to interpret the information Michael provided. There seems to have been a chain of command with middle managers between himself and the editors. This often leads to a command and control type leadership style. According to Michael the Editors told him one of their storylines was “too sensitive to be prodded at in a humorous way” and the “Times made it clear that we were not allowed to offend anyone, or handle any but the safest material”. So this does suggest the editors found their work bordering on the unsuitable for their readers despite claims they might make that they support “conflicting views and challenging perspectives”.

Personally I have no idea what it is like to be edited by hobbits but maybe Michael & David could find themselves a more accommodating publication not run by hobbits.

Of course

A great deal of what happens at the Times depends on who in the chain of command “likes” you. Not you the artist/writer, or the messenger who carries strange comments to you, but who likes and protects the original creator of those strange comments. If the protector, who is three or four or more times removed from the artist/writer, loses status or retires or dies, the blithering idiot who “changed the wording of Donald Rumsfeld’s letter to the IRS when we quoted it directly”is no longer covered and tends to waft away. This is probably true of all major corporations, but it’s no way to run the nation’s newspaper of record.

“They also changed the wording of Donald Rumsfeld’s letter to the IRS when we quoted it directly”

I liked the Easter bouquet cartoon. The only offensive part of the post was the unjustified, random insult to hobbits.

I’m with Kim, these comics don’t seem very fresh or insightful to me. This is like lowest common denominator internet humor – satirize “everything” so you don’t have to think that hard about what you’re trying to say.

Though it is dickish to wait until the art is done to edit the script.

Pingback: Links der Woche 3/15: Charlie, El Eternauta, Star Wars | Comicgate

Noah, upon rereading this post, I’m struck by your first comment. Your initial, most instinctive outrage was invoked not by moral cowardice, nor tastelessness, nor even the dearth of minimal wit required to get the joke — all those were to be expected — but by the simple, nonsensical stupidity of trying to apply the style guide to a comic strip. I am often similarly astonished by mindless, but diligent attention to detail, and I applaud your reaction.