I’m really appreciative to all the Francophones on various sites who have taken the time to put Charlie Hebdo’s work in a rich cultural context, opening up the magazine’s visual aesthetic and clarifying their editorial and political vantage point with more nuance than most of our mainstream Anglophone sources. These people’s willingness to do the tedious work of translating image after image, kindly and with probably strained patience, has elevated a very stark conversation into a vastly more nuanced one.

Here we have a convergence of so many issues that compel our culture to debate: free speech, extremism, faith and fascism, violence, humor, bullying, mockery, racism, sexism, and art. And yet so many opinions seem to fall broadly into one of just two camps – the ones that just outright call CH racist, and the ones that cloak it in the venerable mantle of satire.

Anyone who has ever had the misfortune of a long discussion with me on the subject of satire knows that I really just, generally, don’t find any aesthetic pleasure and only very limited intellectual pleasure in satirical work. Even when it’s very well done, it is a mode of discourse that relies on a spectrum ranging from discomfort to derision, and my response is almost always to turn away on purely emotional grounds. I’ve been very open about this opinion; it’s not new this week. It’s made me feel very awkward about adopting the “Je Suis Charlie” hashtag, because I wouldn’t have said something like that before last Wednesday’s events. The hashtag makes the magazine a metonym for all the people killed – even the Muslim policeman. I respond strongly and decisively to those who were killed and wounded as people, with voices and rights and subjectivity. But I respond to the magazine and the cartoons with ambivalence – because even though I tend to agree with the politics, the aesthetics are beyond me.

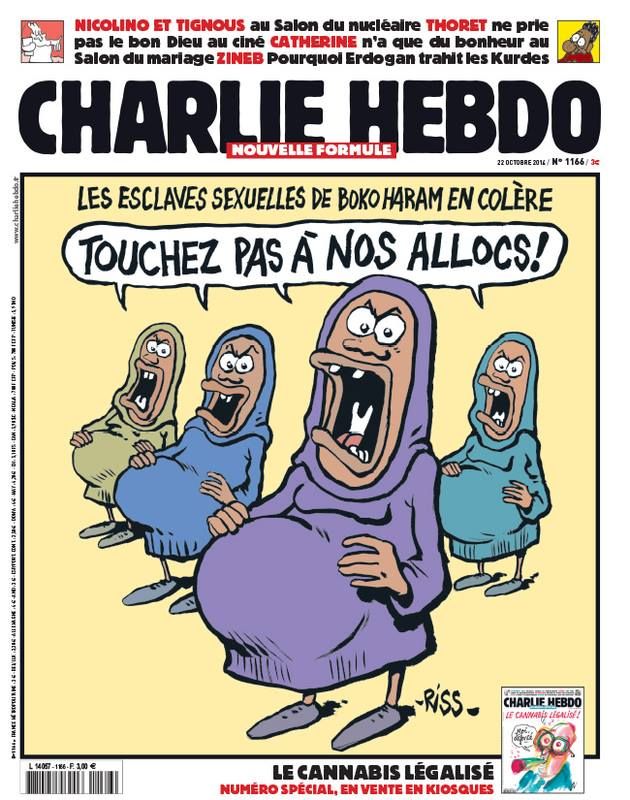

Probably for that reason, my reactions are not substantially mitigated by actually understanding the satire, although it helps. The logic of Charlie Hebdo’s satire is certainly much clearer to me now that so many people have spoken patiently and eloquently to clarify it. In particular, the cover depicting the sex slaves of Boko Haram as welfare queens appears much smarter and more complex when interpreted as “why do you care so much about these threatened and disadvantaged girls, but not about the threatened and disadvantaged girls right on your doorstep?” I am convinced that much of the work is indeed more complicated — and certainly contextually rich – than appears at first glance to readers who do not inhabit the immediate cultural context. These are political cartoons, and politics is always contextual.

But I don’t think there’s any amount of context that will make me find that cartoon less viscerally off-putting. It’s just so ugly to represent those girls that way. The explanation makes sense, but it doesn’t change my aesthetic reaction. It doesn’t feel ok to use their horrifying experiences, even for some noble cause. The complicated reading makes my reactions more complicated too, but it doesn’t make the negative reaction go away.

And even if the explanation did actually make me like that one, not all the cartoons yield to complicated readings. Some of the work really does seem to be simply calling a stupid fig a stupid fig, nothing more than making a wrongheaded idea look sickly and unappealing by shining a puce limelight on it. Basically an intensified form of caricature, It’s a tactic embraced by a lot of contemporary satire. It’s popular – a lot of people really do like it. But I’m not one of them. I’m not sure that type of satire, whether it occurs relatively gently on the Daily Show or with poison incisors at Charlie Hebdo, is anything more than vulgar mockery – even if it’s not racist, sexist, imperialist or otherwise. I’m not convinced it’s a meaningful way to deal with stupidity and wrongheadedness – at least, it doesn’t really seem to be trying to change the wrongheadedness so much as it seems like gallows humor for people who see no possibility of change. It doesn’t recast the stupid thing in a way that raises questions and doubts among the community that believes it or even tolerates it; it doesn’t get inside the heads of the people who think the wrongheaded thing and challenge their motivation or logic; it just puts people on the defensive. The target doesn’t feel outsmarted; they just feel disrespected.

In what way does that serve a positive end or increase our overall intelligence? Doesn’t satire need to be effective at challenging and destabilizing stupid beliefs if it is intended to have political power? If it only reaches people who don’t hold the belief, isn’t it just mockery? Mockery just ends up creating a group identity among the people who collectively believe the stupid thing is stupid. I think that may be why people react so negatively to this kind of imagery – even if it doesn’t actually qualify as racist (and I will refrain from an opinion on that in this particular context that is not my context), it does alienate and separate, working against solidarity rather than increasing it.

So faced with the difficulty of feeling intense compassion and so much horror at Wednesday’s events, yet not quite feeling the identification with Charlie Hebdo that the “Je Suis Charlie” hashtag implies, I am left with an intellectual’s inward-looking response, trying to explain to myself why it just doesn’t feel quite honest to use the tag. I know I am not Charlie Hebdo’s target audience. I struggle to appreciate satire even when it’s really obviously well done. I am stopped by the tone and the feel of the work. I cannot spend enough time with it to understand. But that means the nuances of my emotional and aesthetic responses to this kind of work are largely inaccessible to me – I can intellectually see why much of this work is satire, but I can’t experience it as anything other than raw and ugly and mean and sad.

Again, I am indebted to conversations that catch me up in ways I can’t do myself. In response to the original version of this comment on Facebook, a friend made a comment that struck me as important – “who are outsiders to presume to ‘cast doubt’ on someone else’s beliefs?” Outsiders don’t speak from a place of profound understanding. An outsider’s satire doesn’t know; it just knows better. And when I tried to think of satire that I like better than most, I noticed that Stephen Colbert and Jonathan Swift both rely very heavily on the first person, which is a way of “inhabiting” the person and ideas being satirized. I think the first person is a little sop to people like me, who are put off by how much emotional and critical separation is necessary to make satire work.

This is, perhaps, what makes Charlie Hebdo’s Boko Haram “welfare queen” cartoon so particularly hard for me. What am I supposed to do with the empathy and sadness I feel for the kidnapped girls? Just transfer it over to the welfare moms – as if empathy is generic and disconnected from each group of women’s real stories? The pregnant bodies in the cartoon are named as the “sex slaves of Boko Haram,” the cartoon asserts that they are speaking. But it’s not their voice and their story and their point of view – it’s the voice of the “welfare queens.” The reality of those girls being forced into sexual slavery is alluded to through the pregnancy, but it’s sidestepped and displaced into the significantly different resonance that pregnancy carries in discussions of welfare and indigence. Any identification with anybody here is uncomfortable and unsatisfying – to “get the joke”, to see how smart it is, everybody must be kept at emotional arms’ length.

Clearly I’m just not supposed to react to it this way. Is it even possible to simultaneously satirize and empathize? I don’t know that it is – it is certainly easier to avoid satire altogether than to find the hypothetical example that succeeds at this. And first-person does get very complicated very fast when the subject being satirized is “other” from the satirist in some palpable way – like race or ethnicity or religion. You bang quickly up against issues of authenticity.

And yet – I’m not typically much for authenticity so I’m not entirely comfortable with that, either. Surely it cannot be impossible to satirize someone different from you. That’s why I initially went with the “getting inside someone’s head” – surely the greatest satirists understand their subjects in some profoundly incisive way, not just knowing that they are wrong, but comprehending why they believe they are right.

Perhaps in all of this, I am just missing human nature. It is not human nature to inhabit the minds of people whose beliefs are anathema to us. And surely satire cannot be truly politically effective if it discounts human nature. So all this has brought me back to again concluding that I just don’t like satire, or appreciate it, or enjoy it.

I suppose it has to be said, in all of this, that the use of violence against speech is never anything other than brutal totalitarianism, regardless of the speech and regardless of the violence. But I think about mockery and judgment and how destructive and alienating they are. And I want to be able to understand what distinguishes, on one end of a spectrum, the great artistic and political tradition of satire from, on the other end, plain old bullies mocking people and ideas they don’t like because it makes them feel superior. Understanding is not as easy, I think, as I would like. Satire traffics in mockery and judgment, and the world already has too much of those things and too little connection and justice. I cannot be Charlie, because I am an outsider, and I do not understand. But perhaps I can be Charlie, since by their own logic, being an outsider is good enough.

________

For all HU posts on Satire and Charlie Hebdo click here.

Well, I must say, I respect this piece much more than the last Hooded Utilitarian piece on the Charlie Hebdo attacks, which made no attempt whatsoever at nuanced understanding of the CH cartoons, and painted with such a broad brush as to seemingly endorse Islamist homophobia as a valid concern to be respected.

I’m not really interested in those people who think basic free speech rights are up for revision. As far as I’m concerned, “offensive” images have the right to be published.

But that said, there’s deeper question of how well satire works, what is actually communicated to its audience, and whether it fulfills its intentions. That’s a deeper question, one that’s not only valid, but vital if satire or political art is to move forward.

And it is certainly the case that not just satire, but political art in general mainly communicates a message of “hooray for our side” more than one that changes someone’s mind about a subject. (Don’t even get me started on the “political art” or young art school students who feel compelled to do “political” work for its own sake rather than having anything really to say on the subject.)

Perhaps the question should be, what are examples of really good, effective political art/satire and what makes them work?

Well, there’s “A Modest Proposal”, which I think Caro references. Hard to know if that changed anyone’s mind, or even if it was intended to. It seems to come from a place of horror and despair, rather than from hope of change (at least in my reading/memory of it. It’s been a while since I looked at it.)

That sense of moral commitment can often be missing from contemporary satire…

“Well, there’s “A Modest Proposal”, which I think Caro references. Hard to know if that changed anyone’s mind, or even if it was intended to. It seems to come from a place of horror and despair, rather than from hope of change (at least in my reading/memory of it. It’s been a while since I looked at it.)”

Well, that was my thought exactly. I’ve read “A Modest Proposal” in English 101, as many have. But what I don’t know so much about was what if any impact it had in British policies or public opinion of the time.

If there’s one example I often think of in terms of “great political art”, it’s Spike Lee’s “Do The Right Thing”. Not really satire, of course, but a very effective political film. Its willingness to humanize even the worst of its characters, not to mention the fact that its a fantastic piece of cinema, made it reach many more people than might have otherwise would have normally been sympathetic to Spike Lee’s politics.

In terms of actually causing political change (or at least contributing to change), “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” is the big example in American history. But that’s melodrama, not satire.

I think people can downplay the importance of preaching to the converted, to some degree. Political change often happens not through convincing others, but through consolidating coalitions. Media helps tell people what their side thinks. If you’re this sort of person, this is the side of this issue you’re on. So maybe satire helps with that, sometimes.

I think Caro definitely makes the point that it consolidates coalitions– and that consolidation becomes more of a problem than an asset to diplomacy (and human decency.)

Caro, I really appreciate this piece, and sympathize with your aversion to satire. In line with that, I feel like I’ve struggled to find meaningful, nuanced, interpretations of Charlie Hebdo’s work. I haven’t searched for it, but everything I’ve encountered has been in the “Its French, stop whining,” or “Its French, so you can’t possibly understand it,” veins.

Even Vox published a disappointing defense of one cover, the one showing a Muslim man and CH representative sloppily making out amidst the charred ruins of the CH office. I feel like this cover is cited most often as a “You don’t get the whole context” example– (Look! See! Its the ruins of their firebombed building! That really happened!) Its hard for me to see this cover as one reaching out to a common humanity, however irreverently. It seems to me its reaching out to a common inhumanity. Its honest– CH seems to be saying that the two are locked in an endless embrace of violence, perpetuated for the sake of each other’s pleasure and attention seeking. They love to hate each other, in other words, and the higher the damage count, the higher the sales/conversion of alienated youth into radicals. Its insightful, but nasty.

All in all– are there published, pro-CH critical voices you can recommend?

This is getting pretty far from Charlie Hebdo, but to counter Caro’s dislike of satire, I can think of a few pop-culture works that blend satire with empathy. (I’m not sure whether they use them both at the same time, though.)

One of my favorite episodes of The Simpsons is “Lisa the Sceptic,” in which the people of Springfield find what appears to be the skeleton of an angel and a warning that “The End will come at sundown.” Most of the episode is devoted to making fun of the religious hysteria and mob mentality that ensue, with people burning books and destroying museums in an anti-scientific frenzy and 8-year-old Lisa Simpson remaining the town’s only voice of reason. At one point, Lisa asks her mother, “What kind of moron would believe we found an angel skeleton and that the world might end at sundown?” Marge replies, “Well, your mother, for one,” and Lisa is disgusted at her mom’s gullibility. As sundown approaches, everyone in town gathers together at the site where the skeleton was found, and they hear a voice boom out, “WELCOME TO THE END… OF HIGH PRICES!” The whole thing is revealed as a promotional stunt for a new mall, which the townspeople immediately swarm into in a new frenzy of consumerism. Marge says, “Well, you were right, Lisa. But you have to admit, you squeezed my hand pretty hard when we heard that voice.” Lisa replies, “Well, it was just so loud, and, you know, well… Thanks for squeezing back.” To me, that episode was an almost perfect blend of satire and warmth.

In general, though, I’d say that if you’re really trying to get inside your opponent’s head and understand his or her point of view, you’re not doing satire. I think you need some distance from the object of ridicule in order to ridicule it.

Thank you, Kailyn. :) Maybe we can crowdsource your last question about good, appreciative readings of CH cartoons. Mostly what I’ve seen is people in comments on Facebook and blogs and a few essays like the one linked in the article – even the little bits of context help me recognize the work as smarter than it often appears without the context. But I don’t know of any really strong sustained arguments for any specific piece of work being particularly successful. I maybe haven’t been looking in the right place.

I imagine there may also be some really good arguments for super-acid satire in general, but I haven’t seen one yet that convinced me!

Noah, I think the question is interesting whether satire comes from horror&despair or from a moral commitment. Surely the people who make it think they are speaking from a moral place? Perhaps it’s emanating from a distinct moral place? It’s possible it’s emanating from a moral place that I don’t find particularly moral – it’s an interesting question, what might be under the hood of an aesthetic response.

FWIW, I really like melodrama.

I don’t know that there’s always a strong moral stand with satire…South Park doesn’t seem especially committed to anything, for example. Though maybe they are and I’m just not getting it.

Maybe a moral commitment to mocking stupidity? That seems like a moral principle for some people – to always call out things you think are misguided.

This piece by a former contributor shows pretty clearly that it’s not just confused Americans who have suggested that CH may occasionally be Islamophobic.

Nice to see Caro back being smart here. Surely the Spike Lee film that is “satire” is Bamboozled, not Do The Right Thing. I like them both, actually, (DTRT is one of my favorite films), but Bamboozled was far from the critical success that DTRT was.

Hm, this cartoon is certainly not of very good taste but the fact is that it is impossible to understand out of the context, which was the reduction for the richer families of the “allocations familiales”, which are given to ALL families with 2 or more children (~250€/month for 3 children, for instance) — and were lowered by 75% for the families with higher income (~85000€/yr I think). It has little to do here with “welfare queens”, the target was rather the richer families. The sentence which is put in the mooth of these poor slaves was in fact the moto of the groups defending these families (mostly right wing parties or catholic associations). The meaning of the cartoon is to mock these privileged groups who dare to lament while at the other end, women are kidnapped and raped in other countries. How can anyone understand this if not living in France in Oct. 2014??

Great piece, Caro!

This also is a digression from your specific points about Charlie hebdo and distaste, but I’m so appreciative that the topic of satire is being brought up because I think it’s actually much more huge than people usually appreciate. The birth of irony, I would argue, is the birth of modern Western culture. This is most obvious in literature, which is where I think we get our idea of what a “work of art” is- from Don Quixote to Joseph Andrews to Tristram Shandy to Wuthering Heights to Madame Bovary to Pale Fire, psychological characterization comes through mockery. There is plenty of heartfelt pulp literature, and there are many pieces of thoroughly sincere and earnest “great art,” but the former were the basis for what I think of as modern literature, and the latter are a reaction to it. Irony permits autonomy, which is why it seems like such a peculiarly Western attribute.

Dispassionately watching someone suffer is so central to what it is for us as Western people to enjoy a work of art, that I have somewhat tautologized myself into speechlessness. I don’t know how Caro can like any artwork with narrative content, without some knowledge of cruelty, but I also recognize that we do section off a certain area of “discourse” called “satire.” Nonetheless, I would like to poke at the idea that freedom of speech is so sacrosanct as to not be questioned. First of all, why isn’t that sanctity an abridgement of freedom of speech? And also, as virtuous as I do believe it to be, can we never even discuss the possibility of a rational worldview in which such freedom is not an untouchable pinnacle of morality, but is a form of warfare comparable to, if not equivalent to, fists or bullets?

P.S., South Park totally has a moral center. It mocks conservatives pretty much all the time.

Bert, fair enough re; south park. I’ve never watched it that much.

Kailyn : “it’ French”, yes, but it’s not the point. Even as a French, I cannot understand half the front covers if I don’t remember the precise context. Each cover is usually mixing several points of the news, and after a few weeks it is vain to try to make sense out of it. However it seems to me a nonsense to call these guys racists or homophobics, as you can read in some posts. They were constantly criticizing the homophobic politicians, the discrimination in the French suburbs, the european immigration policies, the demonstrations against gay marriage, etc. Some years ago a historical designer, Siné, who had expressed some antisemitic clichés in an article, had been fired. And another journalist who was a bit too obsessed with islam (not necessarily radical) had been replaced too. They were quite aggressive with radical religion or extreme right, but relatively correct otherwise. (There also was some “real” content beyond the front cover, on politics, economics or culture, but I dont think the Kouachi brothers ever had a look.)

I am one of the French citizens (Franco-American to be exact) who bristled at the previous essay attacking Charlie Hebdo. This one shines because Caro is aware of a cultural gap and tries hard to deleanate the contours of what can and can’t be understood as a foreigner.

I would like to add a small contribution to this effort to better understand Charlie: their is a long and vibrant culture in France of crude and crass humor dating all the way back to Rabelais and still being expressed today in France (in television, movies and songs as well as cartoons). I think it comes out in the drawings in the way the character’s body is always depicted as a little revolting (whatever its ethnicity, social class or age). It’s a complete acceptance of the human body as being filled with things that can cause revultion: shit, spit, aging flesh, odorous farts, sweat, the viscosity of sexual fluids…

The crassness is life affirming and spread universally across all social and ethnic groups. It thus keeps it from being used as a tool to marginalize vulnerable minorities. That is humanistic to the core.

Thank you, Eric!

AC: thank you for adding in that additional information about the middle-class recipients of the stipend. I think the only way people unfamiliar with the context can understand the cartoons is either to do lots of relatively difficult research or have people explain, so thank you.

“Irony permits autonomy.” Bert, can you open that up more, maybe?

Ben, that’s really interesting – I knew that about French humor, but I didn’t really connect the dots. I read that some Francophones said the humor in CH was “tasteless but not racist.” Is crass humor in general perceived as “tasteless but still funny” maybe? If this kind of crudeness appears in lots of places, how does one distinguish when it’s satirically crass and when it’s just plain crass? Is crass+politics/culture sufficient for satire? (That may actually be the difference between, I dunno, Dumb and Dumber and South Park…)

And this, Bert, is it really? “Dispassionately watching someone suffer is so central to what it is for us as Western people to enjoy a work of art.” That doesn’t seem right – surely the response to the Passion was never dispassionate distance. Or Tiny Tim?

Maybe I’m misunderstanding…there is so much to think about.

Daniel: And obviously I wouldn’t include that in the brand of humor that Rabelais was known for. Just like it wouldn’t include the postcards of lynched black men once sold in southern states as a brand of American humor.

Caro: I think you’re on to something. If it helps I think It’s Always Sunny In Philadelphia’s brand of humor comes closest to the French tradition I was speaking of. You sense those guys are left leaning humanist when you watch even their crassest humor. But I’m not sure why.

Daniel, I don’t really buy that. Charlie Hebdo raises some pretty important moral issues — some of which are related pretty directly to folks in the Middle East.

Daniel: In his stand up from the mid-2000s Robin Williams made fun of hispanics (they are not on hockey teams because they would take of their skates to “cut” their opponent), and said Muslims had a holiday called “kaboum.” He wasn’t making those jokes in a-historical context. How do you feel about him?

Daniel, I think debates around Charlie Hebdo are in part about Islamophobia, which seems relevant to many people in the Middle East, since Islamophobia is the ideology that justifies imperialist interventions there.

Also…I deleted one of your comments already. If you keep getting more belligerent, I’ll delete more. I’m not going to have this conversation turn into a shouting match. Fair warning.

Jesus, I watched several episodes of It’s Always Sunny In Philadelphia, and I sensed that those guys (who both write and star in the show) are completely loathsome imbeciles who think shittiness and idiocy are inherently adorable.

On the subject of morality and humor–in a long, tedious post I wrote in response to one of Jacob Canfield’s articles, I mentioned that a big part of Howard Stern’s schtick involves having mentally handicapped people on his show to be laughed at and degraded. I actually said that the relatives of those people should have the legal right to murder Stern and his sidekicks, which seems kind of unfortunate in light of the Charlie Hebdo murders. Still, that’s the most extreme example of immoral humor/satire I can think of, unless you want to bring up Nazis laughing about torturing Jews or something; it seems about a billion times worse than racist humor to me. I find it bizarre that Stern has become such an accepted figure in pop culture, beloved even among liberal types like Lena Dunham and Ira Glass.

“Though our brother is upon the rack,” Adam Smith observes, “as long as we ourselves are at our ease, our senses will never inform us of what he suffers. They never did and never can carry us beyond our own person, and it is by the imagination only that we can form any conception of what are his sensations. Neither can that faculty help us to this any other way, than by representing to us what would be our own, if we were in his case. It is the impressions of our own senses only, not those of his, which our imaginations copy. By the imagination we place ourselves in his situation, we conceive ourselves enduring all the same torments, we enter as it were into his body and become in some measure him, and thence feel something which, though weaker in degree, is not altogether unlike them.”

Sounds like the Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius to me! Irony permits autonomy by drawing a clear line between an observer and the pathetic shucks at whose expense s/he mirthfully chortles. It makes the world a Gnostic dreamland of bloated and emaciated zombies. As for Tiny Tim, it’s much the same thing- Scrooge sees his empty future-stool through magical ghost-vision. Dickens uses satire all the time to supplement his allegories. Psychoanalytically he’s a hysteric, who simultaneously perpetuates and punishes the crimes he portrays.

France’s glorious culture (which is glorious, I love Rabelais) does include incredible boatloads of slaughter, it’s true. If some Congolese child soldiers had murdered some Belgian tourists, you would definitely need to have the colonialism conversation, whether or not the particular Belgians had drawn offensive pictures or anything of equivalent scandalousness.

Daniel, as requested, I’ve deleted your comments. Please don’t post here again.

Not sure I’m entirely following Bert…but, are you collapsing irony and melodrama? Both encourage you to enjoy the feeling/not feeling of identity and pain?

I am… although I think melodrama would be nowhere without irony, perhaps I could be convinced of the reverse. Melodrama is actually something I should understand better- is it fair to say that it is a quasi-tragic genre in which pity takes the place of pathos?

I’m struggling to understand what Bert is saying too, but I think there’s something very intriguing about the idea that the satirical mode is somehow definitively or archetypally Western.

Linda Williams describes melodrama as essential to democratic values. Not sure about pity replacing pathos, but basically it works by showing a flawed world and demanding that it be made better. It’s distinct from tragedy, which shows a flawed world and says it must be endured or accepted.

My point, like most things I have to say, is a murky nonentity that I figure out as I am saying it. But I have had this idea that modernity and mockery are not trivially coincidental. If a (Western) dispassionate observer were to collaborate with some jihadis who wanted to set off a giant ideological cloud of feathers with world leaders proudly flaunting their baldfaced hypocrisy before the dispassionate cameras of global high-handedness (while of course ignoring something unspeakable in Africa), s/he/them could do not better for satire than to suggest a bloodletting at a satirical newspaper.

Pity implies a distance that melodrama demands you set aside. For it to be effective I think, you have to make strong emotional identifications with the characters, so if you pitied them it would descend into self pity. Melodrama relies pretty heavily on pathos – but I don’t think it’s ironic or satirical at all – at least, Sirk isn’t, and Sirk is what I think of when I think of melodrama.

Noah, you’re citing “Melodrama Revised?” Williams says that:

1. Melodrama begins, and wants to end, in a space of innocence.

2. Melodrama focuses on victim-heroes and the recognition of their virtue.

3. Melodrama appears modern by borrowing from realism, but realism serves the melodramatic passion and action.

4. Melodrama involves a dialectic of pathos and action—a give and take of “too late” and “in the nick of time.”

5. Melodrama presents characters who embody primary psychic roles organized in Manichaean conflicts between good and evil. (monopathy)

(Williams, “Melodrama Revised.”)

I think the “space of innocence” would be the antithesis of irony, wouldn’t it? You can’t be innocent and ironic can you?

The Linda Williams thing is pretty intriguing- perhaps my distrust of melodrama and Caro’s distrust of satire are, in both cases, resulting from a disinclination toward violence. Isn’t it fair to say that the average action movie, where the murderous good guy is motivated to avenge his buddy and/or family, is a species of melodrama?

Sorry, playing ketchup here… right, no I think irony relies on universal guilt. Irony is Hobbes and melodrama is Rousseau.

Interesting discussion, but is an understanding of the French social/political scene – let alone aesthetics – really necessary to saying je suis Charlie? Cartoons are mass media, and will inevitably be seen by people beyond their immediate context, so I don’t see how subjective offence can be the sole arbiter of what is acceptable to publish. Or that showing solidarity requires complete agreement.

In the UK, the Guardian and Independent newspapers ran todays CH cover, on the grounds that it was necessary to understand the issue; there have been objections, claiming the cartoon is still blasphemous hence islamophobic. HU has shown a few CH cartoons too, of course…

The Williams books I’ve read are Playing the Race Card and On The Wire, so I’m going off of those, mostly.

I think where satire and melodrama might merge is in the urge to a better world, which I think is more basic to melodrama than the various tropes you list. Both are broadly democratic, it seems like, in that they want evil reformed.

Maybe?

Oh, and Bert, action movies are definitely melodrama.

Sean, I think some understanding of the French political scene is in fact necessary. If the KKK had been printing anti-Islamic material (certainly not a stretch) and were firebombed for it, no one would want to say, “I am the KKK,” right? Saying “I am Charlie” implies at least some basic belief that the ideology you’re aligning yourself with is not completely noxious.

Not that I think Charlie Hebdo’s ideology was comparable to the KKK’s; the point is just that there are some ideologies people would not align themselves with, which means that you do need some knowledge (or at least some take) on the French social/political scene to make the statement, this is me.

From an interview with Luz, one of the cartoonist for CH, who late for work that day..

“We are being made to carry a symbolic responsibility that doesn’t figure in Charlie’s cartoons. Unlike the Anglo-Saxons or Plantu, Charlie fights against symbolism. Doves of peace and other metaphors of a world at war aren’t our cup of tea. We work on details, specific points in correlation with French humour and our way of analyzing things à la française.”

“How will you work ?

We’ll continue drawing our merry little men. Our job, as cartoonists, is to create a cartoon around these merry little men, to transpose the idea that we are all merry little men and that we endeavour to make things work as best we can. That’s what cartoons are about. Those killed were simply people who drew merry little men. And merry little women.”

Full interview

http://www.lesinrocks.com/2015/01/10/actualite/luz-eyes-us-weve-become-symbol-11545347/

The reason I bring up action movies is because I think melodrama is perhaps the naive form of ideological theater, whereas satire is the cunning, jaded version. Both can be virtuous, but often are (instead or also) spiteful and provoke violence- for melodrama there’s Triumph of the Will and Birth of a Nation; for satire there’s the crows in Dumbo, there’s Howard Stern, Beetle Bailey, Dark Knight Returns, etcetera. Islam has a diverse and sophisticated culture (we ripped off the Renaissance from Muslims in many ways), but I don’t know that they have ideological theater in the same way. Disrespect is just disrespect, and in the more mercenary organs of an honor culture, disrespect is a call to avenge. Mocking an honor culture is a meaningful and safe ploy in ideological theater, and not in blood feuds.

Lil Marc was a Chicago teenage rapper who made a video disrespecting rival gang members while he and his friends waved guns around- three days later he was dead in a bus shelter. Sometimes theater isn’t just theater.

“Caro, I really appreciate this piece, and sympathize with your aversion to satire. In line with that, I feel like I’ve struggled to find meaningful, nuanced, interpretations of Charlie Hebdo’s work. I haven’t searched for it, but everything I’ve encountered has been in the “Its French, stop whining,” or “Its French, so you can’t possibly understand it,” veins.”

More like, “It’s French, so unless you understand the language and the context of the images (or had that explained to you) you probably won’t understand, just from the images alone.”

To wit, there’s a website now devoted to that purpose:

http://www.understandingcharliehebdo.com/

And no, I’m not saying that understanding the context automatically makes it good satire, in no way problematic, etc. But one should actually make an effort to learn these things before condemning (or blindly praising, for that matter) the images, rather than just go on first impressions, which is pretty much what I’ve seen too many “progressive” US commentators do. (Ironically, in defense of some idea multiculturalism or “understanding the other”, quite often.)

The fact is, several of the images most often condemned as racist were in fact satirizing and critiquing existing racist caricatures and tropes existing in current French discourse. And, yes, there’s an open debate as to efficacy or ethics of critiquing racism by presenting racist images (see the debates around Robert Crumbs work, for example), but the fact that this is what is being done in those images should be acknowledged.

I agree with Iamcuriousblue that this is a big improvement over the ignorant, malformed, frothing, and criminally uncorrected piece by Jacob Canfield. (The management seems not to realize how it looks when he publishes belligerence about others but protests when it’s directed back at him.)

But I don’t see the point of this exercise. I don’t like blue cheese. Consequently I can’t tell a good blue from a bad blue and have no business opining about the difference. Moreover I’m never going to be able to think my way through to a cogent conclusion about them because I’m missing the key component of the experience.

Speaking as someone who enjoys satire immensely and as a high pain threshold for it, I look at this erudite consideration about how it relates or excludes empathy and solidarity and conclude that you’re missing the fun. Satire is a pleasure. Mockery and giving offense are pleasures. There are better and worse examples of satire, mockery, and offense just as there are better and worse examples of dance, or film, or (I assume) blue cheese. Satire has a moral angle but satire qua satire is not moral or immoral any more than cheese.

Condemning a pleasure comes from a horror that someone is enjoying something you don’t, or you do but don’t think you should. This may be appropriate, but if you get it wrong you’re a prig. I want to float the possibility that depending on the degrees involved, it is less of a crime to be a racist than a prig. For the record, I’m not calling Caro a prig (though I am calling Canfield one), but she’s flirting with a criticism that despite her intelligence she can’t hope to get right, because it’s not a matter of intelligence but taste.

In the case of the Prophet though, everyone agrees that they were drawing the Prophet because it offends Muslims and sometimes people get killed. Is that accurate? Liberals are uptight, by nature, but as regards the Muhammad drawing, that’s pretty much a dare offered and a dare accepted– against the backdrop of a bunch of other killing.

That understandingcharliehebdo site is great.

I’m sorry for not responding to everybody here – there are lots of things I want to comment on but haven’t gotten to. But quickly to Franklin’s comment about the point of the exercise: I fully agree that satire is a pleasure for a lot of people, and it’s certainly not the point of the exercise to prevent anybody from taking pleasure in it. I do think, though, that a good many people are defending these cartoons with very lofty claims about Meaningful Political Action and that’s probably overreaching at least some of the time. It’s become somewhat axiomatic that satire is good politics. That’s a more ambitious claim than it giving pleasure. I think people gravitate to Politics as a defense, though, because they don’t think saying “it’s pleasurable” is enough.

I suppose I think that it is enough, surely, but that it’s not as interesting as explanations that tease out the internal logics of pleasure. That kind of work can be complicated, though, and it’s not particularly culturally validated. I think people tend to the poles – either “it’s my taste; it’s just my taste; I don’t need to explain it”, or “It’s smart! Its value transcends taste!” The former is perfectly valid; the latter is bullshit, but neither really gets at questions of why it’s pleasurable and how that pleasure works artistically and culturally – and politically, too, as politics is very influenced by aesthetics (especially the aesthetics of social behavior.)

In this essay I’m basically trying to tease out the internal logic of my displeasure – the best shot I can make, given my taste, at kicking off that project because I think it’s interesting. But I agree it would be much better served (as in Bert’s comments) by someone who has the taste for satire but is equally interested in these internal logics of why we find it pleasurable and powerful.

Salman Rushdie wrote Satanic Verses and more Muslims were offended by that than Charlie Hebdo as he received an official death sanction. So should Western Nations have banned Satanic Verses? Should I as a westerner feel guilty in buying the Satanic Verses?

Should all western publications not draw any depictions of the prophet Muhammad. Should western publications drop the word prophet from describing the prophet Muhammad which is also considered to be offensive.

As Non-French westerners should we impose our aesthetics on the French?

As armchair westerners that are non muslim should we pretend to know what the average muslim thinks of these cartoons?

Personally I found the Christian cartoons from Charlie Hebdo an order of magnitude more offensive than that claimed to be offensive to muslims.

Charlie Hebdo was a small small publication with a circulation of 60,000 targeted at political aware French moderately intelligentsia.

Finally I hear that George Clooney has ordered his copy of the next Charlie Hebdo and he seems to be someone that endorses cultural sensitivity – but I could be wrong here.

There seems to be an assumption from those calling for context that the biographical context of Jacob’s post is of someone who does not speak French and is not familiar with French culture. That assumption is in fact incorrect. Which doesn’t make Jacob right or anything, but does seem to raise some questions about the work the call for context does, or is intended to do, in the name of free speech, or policing speech.

Somewhat related…I think, as Caro suggests, there’s often a belief, expressed by fans of whatever artform or style, that to understand the artform or style, you have to be committed to it. Only fans can understand, if you disagree, you’re at best confused, and at worst a philistine.

That doesn’t really fit with my own experience with criticism or art. I often learn a lot from folks who don’t like things I like, or who are alienated from them. Caro’s helped me think about Quentin Tarantino a lot, as just on example, though she hates him, and I think her take on him is largely off base. I’m pretty committed to satire as a form, but I think I’ve learned quite a lot from this discussion. I feel like people with outsider perspectives can often provide different insights that aren’t necessarily available to folks who are closer to a topic. There’s no one way to view art, I don’t think. And it’s hard to understand why something is a pleasure until you also understand why it isn’t (or may not be).

Is Charlie Hebdo art or is it just a weekly communication for a 45,000 slightly anarchic community of political aware French people – to be thrown in the garbage at the end of the week like any other current affairs journal.

Noah – Maybe we have a different take on the je suis Charlie thing? I don’t personally think expressing solidarity requires or means total endorsement. Of course, I wouldn’t want to align myself with anything “noxious” – I wouldn’t say je suis flic, for example – but it doesn’t seem like much in depth knowledge is needed to differentiate the CH lot from the French national front.

To be clear – I DO think an understanding of the context is useful, but I was trying (badly it seems) to make a more general point about the impact of cartoons in the wider world. If someone is offended by an image, all the cultural analysis in the world isn’t really going to make it more acceptable to them. From some of your recent HU comments – and apologies for getting away from the original post a bit – this seems to be partly in tune with your position. That the cartoonists intent shouldn’t be privileged over the perspective of French muslims as a marginalised group…?

I’m neither a francophone nor all that familar with French politics and even I could tell that Jacob’s interpretations were bogus. Cultural familiarity and linguistic entrée do you no good if you don’t have the humility to consider whether the tantrum you’re having comports with reality. If Jacob does speak French and is familiar with French culture then his remarks are even more irresponsible than if he was an ignoramus. I guess that settles whether they stem from incompetence or mendacity.

Sure, the perspective of astute outsiders can be informative, but the harder problems of the genre are worked out by the people who participate in it with gusto. Caro may not like Tarantino but I assume she likes film. If she doesn’t care for satire across the board that’s a different thing.

Isn’t there a contradiction in doubling down when you got the context wrong and simultaneously calling for humility though? I guess that’s what I’m saying (and Kalyn as well); at some point the call for context context seems less like a call for scholarship or humility, and more like a rhetorical move.

” but the harder problems of the genre are worked out by the people who participate in it with gusto”

I don’t think that has to be true. To me, this post really suggests it is not true. I think Caro is grappling with difficult problems around satire which wouldn’t necessarily be visible if she were invested in the genre. Among other things, I think she points out the way that satire is itself in many ways an outside endeavor, which requires, or depends upon, a certain kind of alienation.

Every so often a politician who opposes abortion makes a gallingly wrong statement about the female reproductive system, or a politician who opposes guns betrays an inability to distinguish a clip from a magazine. Jacob has made that order of error. It’s not a “rhetorical move” to say that such mistakes should be prevented and they should be put right when they occur.

I’m also not “calling for humility,” but the difference in sophistication between Caro’s piece and Jacob’s is testimony to its value. Caro is at least asking interesting questions but without accounting for what we want from good satire (“we” being we who like it) she’s doomed to get no answers.

“but without accounting for what we want from good satire (“we” being we who like it)”

Again…satire makes political claims, often. So it seems worth trying to account for it in terms that speak not just to those who like it, but to those who don’t. Among other things, is it really just a form of enjoyment, with no more political aspirations than, say, a sit com? (though a sit com can have such aspirations too.) Isn’t the moral force of satire precisely that it speaks to, or shames, those who don’t like it (and are its targets?) Of all forms, it seems odd to make satire entirely a matter of aesthetics.

Someone says French muslims are a marginalised group? Is that true or just an armchair assertion. I would hazard a guess that French muslims enjoy more freedoms in france than they have in a muslim country such as Saudi Arabia and Iran. If lets say Christians settled in Saudi Arabia or Iran would we expect Saudi Arabia or Iran to change their cultural practices to accommodate sensitivities of the Christian minorities. I do sense that the Je Ne Suis Pas Charlie is more than that which it presents it self at face value. I sense double standards, clear trawling through thousands of images to find a select few to make their predetermined points and predetermined accusations. Even the images that were presented were pretty mild and of a standard style.

” Is that true or just an armchair assertion.”

Lots of people who live in France, including Muslims, say that they face prejudice and discrimination. This is true throughout Europe, and indeed it’s true in the U.S. (See Arun Kundnani’s book, “The Muslims Are Coming.”)

Folks sometimes tell African-Americans that they should be grateful that they live in the U.S., because they’d be worse off in Africa. Those arguments seem like they’re in bad faith to me. Someone else over there being horrible doesn’t abrogate your moral duty to your fellow human being. You’re responsible for you, not for folks overseas. (And the west often supports dictatorships in places like Saudi Arabia, so…)

I think the CH folks would not thank you for calling their images “mild”. They were pretty clearly out to offend. You can argue about the exact meaning of the images, and insist that they picked the right targets, certainly. But they had targets.

I’ll add this defence piece – see link below. I think as always we have a complex contextual situation. I suspect many issues are being lumped onto Charlie Hebdo. Charlie Hebdo is not the source of the multi – societal – cultural issues that are being raised. It is small target niche publication with its house style that received death threats from muslim extremists from some time ago, but refused to change its style – and this seems to have been supported by the French people.

The carrying out of the threat has as the French people have said hit them hard – this is their 9-11 they tell us. Charlie Hebdo is being supported by many groups which have a history of cultural sensitivity. Nearly everyone that is familiar with the publication says it is strongly anti-racist but offensive in a traditional anarchic way. They do not set out to target any group they just present the current affairs week on week and cover the stories relevant to that week in their own inimitable anarchic uncompromising style.

The discussion has taken place some initial movement of position has happened but now I see entrenched positions. There is no more movement it just remains to recognise the differences of opinion. I think everyone agrees some of the cartoons can be in your face offensive if you are not used to their week on week style. The major differences is that one group – mainly the French – say that it is antiracist free speech. Another group largely made up of externals stick resolutely to them being islamophobic and racist. And that’s it. If someone wished to start a campaign to close down Charlie Hebdo then that may be the best way forward for that group. Best wishes and thank you for the intelligent articles and commentary that has helped me understand what all this has been on about.

http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/lliana-bird/charlie-hebdo_b_6461030.html

“The major differences is that one group – mainly the French – say that it is antiracist free speech.”

This just isn’t the case. There has been considerable debate in France about Charlie Hebdo’s racism and Islamophobia. I linked one such piece from a former contributor to the magazine downthread. I’ve seen other Francophone writers who are not fans of the magazine either.

Context is good, but I think it’s simplistic to assert that there’s only one context, and misleading to suggest that there was no criticism of Charlie Hebdo within France. The calls for everyone to support the magazine are understandable after the attacks, but they shouldn’t retroactively erase the fact that the magazine had its critics.

Anyway…I’d prefer to focus this discussion on Caro’s piece rather than on Charlie Hebdo more generally. We have another piece on Charlie Hebdo going up today that I think is probably a better place to debate those issues, if people want to talk about them and can hold off an hour or two…

I’m not calling “to make satire entirely a matter of aesthetics.” I have no idea where you got that. I’m calling for sufficient delectation in the genre to make further consideration meaningful and productive.

If it’s not a matter of aesthetics, though, then “delectation” seems like it has to be a marginal issue.

You could say it’s an aesthetic issue; then it only matters to aesthetes (arguably) and they are the ones who should discuss it. If it’s a broader moral and political issue, then relegating the matter to fans ends up saying that only fans get to weigh in and arbitrate matters of broad political and moral interest. That seems wrong to me.

It’s pretty specious to claim that all understanding of a cultural form relies on pleasure. Displeasure seems like a quite productive starting point, as long as it’s an informed position. Looking at it dispassionately as a machine that enables desire is a perfectly legitimate approach too, especially when evaluating political and social meaning.

I wrote about related issues at the LARB recently, if anyone’s interested.

I’m really making a very simple claim here: if you don’t care for a whole genre, you’re limited in what you can say about an example of it, and certain aspects of the genre are going to strike you as mysterious. I’m talking about taking pleasure in a genre, because it is a pleasure to those that enjoy it. That’s not to claim that it’s aesthetics all the way down or that “all understanding of a cultural form relies on pleasure.”

Though looking at political and social meaning “dispassionately as a machine” isn’t legitimate at all. It’s monstrous. Jacob thought that his interpretations were analytical and objective and look where that got him.

New post by Ben Saunders is up here.

I doubt Jacob thought his take was objective, whatever that would mean when looking at aesthetic objects.

You’re not just saying that those who don’t care for a genre are limited. You’re saying that they’re *uniquely* limited. That is, you’re saying that those who care for a genre have a better, more complete view of the genre. And I think that’s incorrect, for reasons I’ve already discussed.

“Monstrous!” That is kind of hyperbolic, but amusing. So Franklin, since your experiencece grants you unique insight (how multicultural!), is Charlie Hebdo good satire or bad satire?

I quote: “These are, by even the most generous assessment, incredibly racist cartoons.” That is to say, they are racist not just by my assessment as Jacob Canfield, but any assessment that anyone would make – they are objectively racist. Note the reification: “these are racist cartoons,” not “I felt offended when I read these cartoons,” which is really what happened here. Caro isn’t making that mistake – “I find this cartoon viscerally off-putting” – because Caro is capable of wondering whether she’s correct.

you’re saying that those who care for a genre have a better, more complete view of the genre

I said more complete; you said better.

@Bert: Asking whether Charlie Hebdo is good satire is like asking whether the New York Times is good journalism. Efforts can only be judged one at a time.

Okay; you say more complete. I don’t agree with that either. I don’t believe that inside means more complete than outside.

Caro’s piece is a personal essay. Jacob’s is a polemic. You’ve correctly identified different genre markers, yes.

Of course inside is more complete than outside, that’s the whole point of being inside. I adore art and have been writing about it for twenty years. I’ve read thousands of pages of germane literature and have seen tens of thousands of objects. Someone who doesn’t care much for art who wants to have a go writing about it one time may have some novel insights, and I would willingly read them. But we don’t and shouldn’t expect him to have big-picture domain knowledge to compare with mine.

You’ve correctly identified different genre markers, yes.

I’ve correctly identified the quality markers as well.

Okay- I actually could talk about whether the NYT is good journalism, overall, aesthetically or otherwise, but okay- the Boko Haram cartoon. Is it funny? Why or why not?

“Someone who doesn’t care much for art who wants to have a go writing about it one time may have some novel insights, and I would willingly read them. But we don’t and shouldn’t expect him to have big-picture domain knowledge to compare with mine.”

But they might have equally valuable knowledge from another domain. That’s the point, for me anyway. An insiders view is valuable, but it’s not better, nor necessarily more complete. Again, this is kind of the great thing about art. It’s not engineering, where expertise really means expertise in a fairly straightforward way — someone who knows how to build a motor knows how to build a motor, and that’s more or less the end of that. But you can study art forever, and your take isn’t necessarily more objectively “right” than someone who is just a casual passerby, and they might well see things you don’t (or even see things more completely.)

You’re using words like “valuable” and “better” on my behalf when I’ve said nothing of the kind. “Complete” just means “complete.” There are people with complete domain knowledge who are missing some other critical virtue.

But in practice, outsiders throw in some good stuff here and there but advantage finally goes to the lifers. Spend time with Jed Perl’s new anthology of American art writing and you’ll see what I mean. Henry Miller wrote some charming things about painting but he’s no Clement Greenberg. I can ask Irving Sandler about long trends in art criticism that I can’t ask the guy who just tried writing about art once for the first time last week, and there are a lot more people around who could say something clever about art than there are cats like that. Jed Perl, for that matter, has gone from good to extraordinary over the course of thirty years.

As for the Boko Haram cartoon, by the time I figured out the references it was too overexplained to really feel the humor. So I didn’t pass much judgment on it.

Well, the lifers are more likely to write more about it, that’s certainly true. The best film criticism ever written was written by James Baldwin, though, not by someone whose main job, or life’s work, was film critic. I don’t think that’s necessarily especially unusual.

Nobody has complete domain knowledge, not least because domains (or genres) are porous and ill-defined.

I happen to think Clement Greenberg is more interesting than the kids (or middle-aged people) these days give him credit for, but to claim his writing as a universally (or even widely) agreed-upon standard for professionalism is a joke. My friend Randall Szott, with whom I strongly disagree about art but is without question a thoughtful and informed adversary, detests art criticism, and contemporary art as a whole. Here’s a sample: http://randallszott.org/tag/art/

Of course an observer of dolphin sex can’t experience what dolphins experience while having sex, but s/he can have lots of thoughts about it– and Kant, of course, requires that a disinterested gaze is necessary for aesthetic appreciation. Pleasure is the enemy for Kant. As someone with no lack of interest and erudition in popular culture and things literary, saying that Caro is not in a position to judge satire seems ridiculous.

In fact, I want to suggest that perhaps her entire post is in itself a cunning satirical deflation of our frothy over-valuing of satire. And if I don’t “get it,” is it because her satire isn’t funny enough, or because I need to speak French, or what?

I definitely think Bert’s move of marking satire as essentially Western and essential to the evolution of Western thought is something I’ve read before and not by Bert. By some 1950’s literary critic or some such, wish I could place.

Also want to thank Noah for posting the link to the bit by the former CH contributor who takes CH to task for being increasingly anti-Islam and anti-immigrant in an article written before the shooting. It’s interesting and gives an angle I hadn’t heard before. It’s particularly interesting since he really grounds his case of their bad behavior in their print journalism, not their cartoons.

And great piece Caro. I find your perspective really alien but really interesting. If one doesn’t appreciate satire much at all, CH is surely going to seem fairly indefensible, since it isn’t particularly great as satire. I suspect that many other folks attacking CH share your tastes and it puts the whole conversation in a different perspective for me.

Were you a CH reader and fan, David? If so, maybe you could talk briefly about why you like it?

The Wikipedia entry on satire has a whole section on Muslim satire- as with the rest of the intellectual pursuits known as “Western culture,” Islam apparently kept satire going after the Roman Empire shit the bed.

Let the last word on the subject of Charlie Hebdo come from a one-time editor of the magazine, who sent his former colleagues this cri du couer in response to a op-ed piece in Le Monde written by ‘Charb’ (one of CH’s slain cartoonists) in 2013. This is a translated reprint of Olivier Cyran’s response to Charb’s opinion piece, justifying his magazine’s putrid and hypocritical stance on Muslims (all in the name of anti-racism, of course). Like this paragraph:

“You claim for yourself the tradition of anti-clericalism, but pretend not to know the fundamental difference between this and Islamophobia. The first comes from a long, hard and fierce struggle against a Catholic priesthood which actually had formidable power, which had – and still has – its own newspapers, legislators, lobbies, literary salons and a huge property portfolio. The second attacks members of a minority faith deprived of any kind of influence in the corridors of power. It consists of distracting attention from the well-fed interests which rule this country, in favor of inciting the mob against citizens who haven’t been invited to the party, if you want to take the trouble to realize that – for most of them – colonization, immigration and discrimination have not given them the most favorable place in French society. Is it too much to ask a team which, in your words “is divided between leftists, extreme leftists, anarchists and Greens”, to take a tiny bit of interest in the history of our country and its social reality . . .” ?

*But of course, some of you will consider my refusal to uphold CH’s ‘humor’ as a fearless and vanguard stance as some sort of endorsement of censorship. CH had (and has) the right to publish whatever it likes without any argument from me advocating limits on free speech. But for those of you who insist that we all wholeheartedly endorse its editorial content as a way to condemn the mass murderers responsible for these deaths, I suggest you look at the real world consequences of CH’s success in getting leftists in lockstep with Europe’s increasingly hard right policies. Muslim women, who have always been vulnerable to violence at the hands of right wing thugs, now face an uphill struggle for even basic rights, thanks to the kind of policies CH’s editors endorse that have resulted in women in headscarves being ejected from cultural spaces, and now even forbids them from performing public service – all in the name of the bougie-feminist left that unites the non-competing interests of Marine Le Pen with Femen’s topless activists. CH’s editorial stance could be summed up as ‘Freedom of speech for the powerful by the influential and irresponsible – at the expense of the powerless’.

Noah,

Despite your snark, Franklin makes a good case that Jacob believed he was being objective. You make no case for being otherwise.

Sorry, make that believing

We can agree to disagree.

This really should not be the thread to debate Jacob’s piece by proxy, if we can avoid it. Again, Ben’s post is a better place for that discussion.

Pretty good quote, Daniel. Let’s see what the defenders of liberty will denounce it for. Insufficient objectivity? Insufficient subjectivity? Insufficient sensitivity to the elusive French je-ne-c’est-quoi?

Does satire have to be funny, humorous? Are all cartoons appearing in a claimed satirical magazine satire. Is irony satire? If so should irony be humorous?

With respect to Charlie Hebdo I see it as primarily a medium of communication to the 45,000 to 60,000 community of subscribers it was directed to and covering issues of French and international current affairs. It’s house style was satirical but not everything in it was necessarily satirical.

Joyce, a good point. The issue of “is it funny” (or would you think it were funny if you lived there, were Muslim, were an immigrant in Paris, etc.) has dominated some threads in a peculiar way. Satire, irony, and the grotesque do not necessarily lead to humor, or have to.

Bert Stabler,

One argument against Olivier Cyran’s point of view may be found in Olivier Tonneau’s letter on the subject: “I was, however, stunned when I read a very angry article by a writer I admire, Mohamed Kacimi. The son of an Algerian Imam, deeply attached to his Muslim culture yet also fiercely attached to secularism, Mohamed Kacimi lashed out angrily at white, middle-class opponents of the law, who focused on the freedom of Muslim women to dress as they please. They were not the ones, he said, who had their daughters in the suburbs called prostitutes, bullied and sometimes raped for the sole reason that they chose not to wear the veil – let us remember that many Muslim women do not consider wearing the veil as compulsory: again, we have here Muslims being persecuted by fundamentalists.”

With regard the post quoting Olivier Cyran’s letter … the only thing that letter proves is that Olivier Cyran had a personal opinion that was publicly aired. It would have been part of a dialogue, for example let’s say it was part C in the dialogue: A – B – C – D – E – F – G.

Now one could ask what was the point of raising C and then requesting “Let the last word on the subject of Charlie Hebdo” be C.

A little further down the comment we find an assertion saying that C is a “response to Charb’s opinion piece, justifying his magazine’s putrid and hypocritical stance on Muslims (all in the name of anti-racism, of course)”.

So here we have a reference to part B of the dialogue but our commentator slipped in his own label to it. From this one can better understand the purpose of that post.

Personally, when people claim something should be the last word on a given subject, I think to myself isn’t that similar to the methods used by so called extremists?

Yes, Muslim fundamentalists are bad, and murdering cartoonists is bad. The point Oliver Cyran (I guess that’s the letter writer) is making is that it is in fact possible for a society to treat Muslims badly, even if several are fundamentalists and a few of those are violent and some of those shoot unarmed civilians.

I have a general question to everyone that lies “outside Charlie Hebdo” issue.

If someone were to write a book directly critiquing the claims that the prophet Muhammad had any connection with a god, that Islam was just a man made structure, and the Quran is the word of men and not God … should that person be allowed to publish? What advise if any would you give to that author.

Joyce: “Personally, when people claim something should be the last word on a given subject, I think to myself isn’t that similar to the methods used by so called extremists?”

FFS, are you serious? The answer to your question is “no”. Someone saying they think something should be the last word on a comments thread is not the same as shooting you in the head. I understand that slippery slope fallacies are incredibly appealing when you’re trying to win an argument, but could you make some vague effort to keep them out of the realm of self parody?

“Pretty good quote, Daniel. Let’s see what the defenders of liberty will denounce it for. Insufficient objectivity? Insufficient subjectivity? Insufficient sensitivity to the elusive French je-ne-c’est-quoi?”

…and it’s been denounced because all truth is relative. Didn’t see that one coming, did you?

Joyce, isn’t that more or less what The Satanic Verses is?

I think it’s an interesting and not-all-that-easy question when a joke is full-nominative “satire” and when it’s not. Sometimes it seems like we say any joke at all is “satire”. (Bert gestures to that as well, in one of his many excellent comments.)

Wikipedia has an article on “Comedic Genres” that conflates satire with any and all “topical humor”, which seems sort of absurd to me. But it certainly doesn’t offer a broad range of alternative, expressive vocabulary for describing different modalities and tones of humor – the only other really useful one in the list is “wit.”

And even wit and satire are hard to distinguish, if the wit is turned to topical social issues. Take Wodehouse, for example. It doesn’t strike me that satire is the dominant TONE in his most famous work – his characters are often ridiculous but you are demonstrably encouraged to form affectionate identifications with them. And yet he is described as a “satirist of English society” as often as he is descrbed as “one of the 20th century’s greatest wits.”

Huh…Wodehouse really doesn’t seem very satirical…. I guess very gentle satire? It’s certainly hard to see upper class Brits being upset at the portrait of Bertie Wooster….

Hi Caro, no not in the nature of Satanic Verses. I am thinking of a direct challenge to the claims of Islam and an analysis of the claims of the institutions supporting Islam. No satire, no irony, just academic and historical. It would be part of a much larger study but that book would focus on Islam.

Joyce, I’m sure folks have done so. I can’t imagine anyone on this thread would condemn such a thing. Why would they?

What you describe bears very little relation to what Charlie Hebdo was doing.

ps the challenge is only with respect to the divine origin of Islam and the divine origin of the sacred texts.

It’s not a challenge! Literally nobody here thinks that would be racist or wrong.

Noah, I don’t think of Wodehouse as all that satirical either. But it’s not uncommon; here’s Orwell:

“In Something Fresh Wodehouse had discovered the comic possibilities of the English aristocracy, and a succession of ridiculous but, save in a very few instances, not actually contemptible barons, earls and what-not followed accordingly. This had the rather curious effect of causing Wodehouse to be regarded, outside England, as a penetrating satirist of English society. Hence Flannery’s statement that Wodehouse “made fun of the English,” which is the impression he would probably make on a German or even an American reader.”

The thing is – is it always satire if you make fun of someone? Is it always satire if the subject of the joke is some topical event?

Yesterday there was a new item that an ultra-orthodox newspaper had edited all the women, including Angela Merkel, out of the photograph of the march in Paris. Someone posted a response that edited all the men out, leaving three women standing awkwardly and alone. Is that satire? Or is it just “visual play” and therefore wit? It’s at least equally wit as satire, surely? There was also a version called the “Million Merkel March” where someone just replaced everybody’s head with the head of Angela Merkel – is THAT satire? It also seems like the designator sort of misses the mark. But I got FB links all day yesterday about how humorists were “satirizing the ultra-orthodox.”

Bert Stabler,

the point of bringing up Kacimi’s letter, as reported by Tonneau, is not that Muslim fundamentalists are bad. It is that when someone like Cyran rushes to the defense of Muslims who he believes are being treated badly, some of those Muslims disagree with his assessment, and resent his actions.

This doesn’t mean that Kacimi is right and Cyran is wrong. But it does mean that there are valid criticisms of Cyran not included in your list of options for the defenders of liberty.

I think Joyce’s point is this.

The basic infraction of Rushdie, on the one hand, and Charlie on the other was in the violation of some sacred principle or tenet — to portray something upon which people place supreme importance in a disrespectful, dismissive, or skeptical way (or to do it at all). In this way, an academic book that said, “The record shows that Mohammed was an ordinary guy, jockeying for his own power and using religion to make it so” or “These texts seems to have come from all different contradictory sources” would equally be a violation of the sacred. They are, in essence, saying that someone or something that you hold sacred is really a fraud, an invention, a completely ordinary worldly event or figure.

So consider a hypothetical scholar — or a real one, like Ibn Warraq — who makes this claim and is threatened or killed. Regardless of what you think of Ibn Warraq’s work (make the hypothetical scholar as reputable as you like). Imagine someone who questions the historicity of Mohammed being attacked for defaming the sacred in such ways. Would we spend much time wondering about whether the scholar was acting in a way that fomented the backlash, that demeaned an already demeaned population? I’m guessing not… but why not?

And this is how things relate back to satire, or maybe more broadly to how works of the imaginations (and especially the visual imagination) can hit home a lot more strongly than dry academic works, even if those works are saying much the same or “worse” things. Fiction conjures up images, and images — well, they do much of their own work, straight no chaser.

Or maybe as Caro points out, it’s really satire or humor that we have a problem with. An academic says that Jesus never existed? No problem. An artist dips a plastic crucifix in urine… or makes a film (maybe even a comedy) about a “human” Jesus… or draws Jesus as a zombie… that crosses the line. But what line has been crossed?

No pun intended.

If a Jewish group targeted David Irving for violence, wrong as that would be, I’m pretty sure that the content of David Irving’s scholarship would be part of the conversation. You would not have people saying, “I am David Irving”, for obvious reasons.

The issue of satire is not contained, or equivalent to, the issue of racism. The effort to make one stand in for another is I think really confused.

Yes, but in general, Salman Rusdie was not threatened because he or his book was racist. He was threatened for showing the prophet as something other than sacred.

Or take the newest CH cover, which I’ve heard very little about about in terms of its putative racism. Still as one (only one, I know) Parisian put it, “I think freedom of speech needs to stop when it harms the dignity of someone else. The prophet for us is sacred.”

Still, you are right: we are more likely to rally behind an artist than around an academic, even as (I think) we are more like to condemn an artist for the wisdom and moral rectitude of his or her work. It cuts both ways.

I mean…it’s somewhat complicated because some extremist Muslims have decided you can’t depict the prophet at all. For the murderers, the issue was blasphemy, not racism.

When folks talk about whether the comics were racist, though, I think they mostly mean that they think the comics are racist, not blasphemous. I don’t know that I’ve heard anyone say that Rushdie’s book was racist (somebody may well have; I just haven’t seen it.)

It’s further complicated maybe by the fact that the West, especially since 9/11, has worked to constitute Muslim as a racial identity in a number of ways. CH’s blasphemy was often racialized; the portraits of Muhammad are racialized caricatures of Arab Muslim stereotypes.

If someone like David Irving said, “the Jewish God does not exist,” that’s blasphemy. If the same someone said, “the greasy, greedy kike God does not exist,” that’s still blasphemy, but it’s also racism. If I said, that’s racism, and you responded, “so you think blasphemy is wrong?” I would get irritated, and I think rightfully so.

This is the internet not a peer reviewed journal (of a reputable standard). Anybody can make a claim on anything (assume free speech). The question those interested in accuracy have to ask is does the claim bear scrutiny …

… what methodology was used, is there any evidence for the claim, how was that evidence selected, was there a selection bias in gathering that evidence, how was the selected evidence analysed, how was it interpreted, was the interpretation biased, are there counter claims to the interpretation, how were these counterclaims dealt with etc etc.

My hope for the internet is that it will encourage learning my fear is that it will encourage stupidity.

Pingback: From the world pool: February 21, 2015 |