Defining the concept COMIC has, perhaps, been the cause of more ink spillage and deforestation than any other single theoretical topic in comics studies. Interestingly (and rather predictably), work on this topic has loosely followed the same trajectory as earlier attempts to define the concept ART.

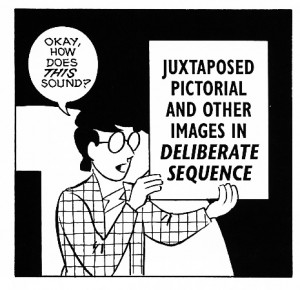

First, we have formal, aesthetic, and/or moral definitions of comics roughly paralleling traditional, pre-twentieth century definitions of art. Nontable examples include David Kunzle (The Early Comic Strip: Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the European Broadsheet from c. 1450 to 1825, 1973), Will Eisner (Comics and Sequential Art, 1985), Scott McCloud (Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, 1993), David Carrier (The Aesthetics of Comics, 2000), and Thierry Groensteen (The System of Comics, 1999/2007). Comparisons are easily made to Plato, Kant, and even John Dewey’s accounts of the nature of art. But, just as the second-half of the twentieth century saw a widespread rejection of any such account of the nature of art that entails that an object is an artwork solely in terms of some properties (whether formal, aesthetic, or moral) that inhere in the object itself, during the early twenty-first century comic studies has seen a similar turn away from formal definitions in favor of other approaches. Interestingly, the three main alternative approaches to defining comics match almost exactly the three main approaches found in earlier, twentieth century work on defining art.

First, we have formal, aesthetic, and/or moral definitions of comics roughly paralleling traditional, pre-twentieth century definitions of art. Nontable examples include David Kunzle (The Early Comic Strip: Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the European Broadsheet from c. 1450 to 1825, 1973), Will Eisner (Comics and Sequential Art, 1985), Scott McCloud (Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, 1993), David Carrier (The Aesthetics of Comics, 2000), and Thierry Groensteen (The System of Comics, 1999/2007). Comparisons are easily made to Plato, Kant, and even John Dewey’s accounts of the nature of art. But, just as the second-half of the twentieth century saw a widespread rejection of any such account of the nature of art that entails that an object is an artwork solely in terms of some properties (whether formal, aesthetic, or moral) that inhere in the object itself, during the early twenty-first century comic studies has seen a similar turn away from formal definitions in favor of other approaches. Interestingly, the three main alternative approaches to defining comics match almost exactly the three main approaches found in earlier, twentieth century work on defining art.

First, there is the outright rejection of either the necessity of, or even the possibility of, a definition of the concept at all. Notable examples of such an approach in comic studies include Samuel Delaney (“The Politics of Paraliterary Criticism”, 1996), Douglas Wolk (Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean, 2007), and Charles Hatfield (“Defining Comics in the Classroom, or the Pros and Cons of Unfixability”, 2009). The connection to Morris Weitz’s (and others’) Wittgensteinian rejection of definitions of art, and his embrace of the “open-endedness” of art, is obvious.

First, there is the outright rejection of either the necessity of, or even the possibility of, a definition of the concept at all. Notable examples of such an approach in comic studies include Samuel Delaney (“The Politics of Paraliterary Criticism”, 1996), Douglas Wolk (Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean, 2007), and Charles Hatfield (“Defining Comics in the Classroom, or the Pros and Cons of Unfixability”, 2009). The connection to Morris Weitz’s (and others’) Wittgensteinian rejection of definitions of art, and his embrace of the “open-endedness” of art, is obvious.

Next we have historical definitions – those accounts that locate the “comicness” of comics in the historical role played by particular comics, and in the history that led to their production (and, perhaps, in intentions, on the part of either creators or consumers, that a particular object play a historically appropriate role). One notable example of an historically-oriented approach to the definition of comics is to be found in Aaron Meskin’s work (in particular, in the concluding remarks to “Defining Comics” 2007, which is otherwise rather hostile to the definitional project). Meskin’s comments (and likely any other account along these lines, although this seems to be the least developed of the options) owes much to Jerrold Levinson’s historical definition of art, whereby an object is an artwork if and only if its creator intends it to be appreciated in ways previous (actual) artworks have been appreciated.

Next we have historical definitions – those accounts that locate the “comicness” of comics in the historical role played by particular comics, and in the history that led to their production (and, perhaps, in intentions, on the part of either creators or consumers, that a particular object play a historically appropriate role). One notable example of an historically-oriented approach to the definition of comics is to be found in Aaron Meskin’s work (in particular, in the concluding remarks to “Defining Comics” 2007, which is otherwise rather hostile to the definitional project). Meskin’s comments (and likely any other account along these lines, although this seems to be the least developed of the options) owes much to Jerrold Levinson’s historical definition of art, whereby an object is an artwork if and only if its creator intends it to be appreciated in ways previous (actual) artworks have been appreciated.

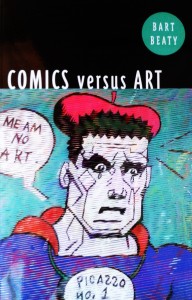

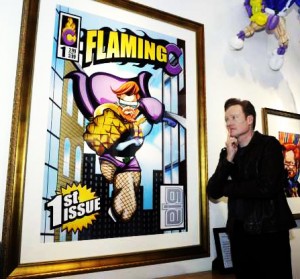

Finally, we have institutional definitions, which take something to be an comic if it is taken to be such by the comics world. The primary proponent of something like an institutional view within comic studies is Bart Beaty (Comics versus Art, 2012). Such views obviously owe much to similar, earlier approaches to the nature of art due to Arthur Danto, George Dickie, and others. Of course, one of the primary challenges here is to determine what counts as the “comics world” in a way that is informative and not viciously circular (i.e., an account where the comics world is not defined merely as those of us who take comics seriously).

Finally, we have institutional definitions, which take something to be an comic if it is taken to be such by the comics world. The primary proponent of something like an institutional view within comic studies is Bart Beaty (Comics versus Art, 2012). Such views obviously owe much to similar, earlier approaches to the nature of art due to Arthur Danto, George Dickie, and others. Of course, one of the primary challenges here is to determine what counts as the “comics world” in a way that is informative and not viciously circular (i.e., an account where the comics world is not defined merely as those of us who take comics seriously).

Thus, the work on defining comics has closely mimicked earlier debates about the definition of, and nature of, the larger category of art (presumably, all, most, or at least typical comics are artworks – even if possibly bad artworks – solely in virtue of being comics). This much seems undeniable, but it also seems somewhat problematic. After all, sticking solely to approaches and strategies that appeared plausible when used to define art is only a wise strategy if we have some sort of prior conviction that the properties and relations that make an object an artwork (i.e. that explain the artwork/non-artwork distinction) are the same properties and relations (or at the very least, the same kind of properties and relations) that make an object a comic (i.e. that explain the comic/non-comic distinction). And to my knowledge no argument has been given that this is the case. As a result, it behooves us to ask if comic studies has been too traditional, and too unimaginative, in this regard. Isn’t it possible that we could be convinced that there is an adequate definition of comics, but also convinced that such a definition should look very different from extant attempts at defining art (i.e. it would take very different kinds of factors into consideration)? And, more to the point, isn’t it possible that such an attitude could be correct? If so, then the close parallel between work on the definition of comics and work on the definition of art seems unfortunate, since it seems to ignore this possibility in favor of recapitulation of past history.

Thus, the work on defining comics has closely mimicked earlier debates about the definition of, and nature of, the larger category of art (presumably, all, most, or at least typical comics are artworks – even if possibly bad artworks – solely in virtue of being comics). This much seems undeniable, but it also seems somewhat problematic. After all, sticking solely to approaches and strategies that appeared plausible when used to define art is only a wise strategy if we have some sort of prior conviction that the properties and relations that make an object an artwork (i.e. that explain the artwork/non-artwork distinction) are the same properties and relations (or at the very least, the same kind of properties and relations) that make an object a comic (i.e. that explain the comic/non-comic distinction). And to my knowledge no argument has been given that this is the case. As a result, it behooves us to ask if comic studies has been too traditional, and too unimaginative, in this regard. Isn’t it possible that we could be convinced that there is an adequate definition of comics, but also convinced that such a definition should look very different from extant attempts at defining art (i.e. it would take very different kinds of factors into consideration)? And, more to the point, isn’t it possible that such an attitude could be correct? If so, then the close parallel between work on the definition of comics and work on the definition of art seems unfortunate, since it seems to ignore this possibility in favor of recapitulation of past history.

So, for what it’s worth, I think I have a good theoretical reason why definitions of comics and art should be similar.

Carl Freedman in Critical Theory and Science Ficiton explains that genre precedes art. That is, the category “art” is itself a genre. A laundry list isn’t art; a novel is. That’s a genre distinction. Art is a genre, rather than the other way around.

That means that both art and comics are aesthetic genres (if art as a whole is a genre, then a medium is a genre too.) So it makes sense to define them in parallel ways.

I’m not sure that attempts to define comics have paralleled attempts to define art because one is a subset of the other. These may simply be common steps in any collective effort to define inherently vague concepts. Some of the same techniques have been applied or could be applied to attempts to define love, culture, ethnicity, justice, or terrorism.

“sticking solely to approaches and strategies that appeared plausible when used to define art is only a wise strategy if we have some sort of prior conviction that the properties and relations that make an object an artwork (i.e. that explain the artwork/non-artwork distinction) are the same properties and relations (or at the very least, the same kind of properties and relations) that make an object a comic”

This isn’t true for the anti-definitional move, at least — if you don’t think any concepts have definitions (which is basically my view), then you’ll think that goes for comics and art and a slice of bread. But that doesn’t seem to rely on a conviction that the properties/relations that are constitutive of the concept COMICS are the same for ART, because it denies that there are any such properties/relations

Jones: Point taken regarding the ‘no-definition’ viewpoint. It’s also worth noting that those scholars who have staked out a particular approach to the definition of comics haven’t themselves necessarily committed to a similar approach to the definition of art. But the general parallels (between the work on these topics in general, even if not necessarily in the work of particular scholars) still seem to hold, and the claim you quote still seems a fair worry for the other positions.

John: You might be right – these might just be relatively natural ways to attempt to define anything (or, at least, any created, value-laden artifacts, such as artworks or comics). But I still think it is striking that, when I pulled out a ‘defining comics’ handout that I created for my students, and then compared it to the Definition of Art entry on the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, the approaches matched almost perfectly.

Noah: I just think I disagree with the claim that art is a genre. Of course, we can explain (at least partially) why novels are artworks, and laundry lists are not, by noting that objects falling in the novel genre are typically art, and things falling in the laundry list typically are not. But this only requires:

(1) Things typically falling in the novel genre are art.

It doesn’t require:

(2) Art is itself a genre.

Nor does it require:

(3) All artworks fall into some genre.

I find the last claim (which is implied by your view) very implausible: presumably part of the point of boundary-challenging works (e.g. Duchamp’s Fountain) is to create works that don’t fall into any existing genre, even if they do sometimes lead to the construction of new genres – e.g. ready-mades, in this case, at least if you think ‘ready-made’ is a genre (I am not sure).

I also don’t think comics is a genre, independently of these considerations. I am not even sure comics is a medium (rather than a hybrid of media, corresponding to its historical status as a hybrid of pre-existing art forms). I do think it is an art form. Basically, the logician in me worries that we are too quick to gloss over the distinctions between art form, medium, genre, and other similar classificatory concepts.

I’m not sure I explained myself well. The point isn’t necessarily that art is a genre; it’s that genre classification precedes art. We define art through genre; things in some genres are considered art, things in other genres are not.

That does make art itself a kind of genre, at least arguably — but it also just creates a situation in which the overall category is genre, not art. Art and comics both fit into, or come out of genre. They both are categorized according to genre theory, would be my argument.

I hope that makes sense. I think in some ways it’s just part of Jones’ anti-definitional argument. Art and comics are both aesthetic categories that can be classified (or not really classified) using similar approaches. In my view.

In defence of Noah, I’d argue that the evidence that “Art” (the capital A, fine art kind of art) is a genre is the way in which it exists across different forms; the way that we define something like 50 Shades of Gray as “not art” and and something by Kafka as “art” seems to be a genre distinction rather than a formal one; I don’t especially see that its different from saying Lord of the Rings is fantasy, and it is a conceptually comparable to the way that we distinguish postcard water colours from a Van Gogh.

Noah:

That helps. But if we categorize things as art in terms of categorizing things as members of specific genres, then that still implies that an artwork can’t be an artwork unless it is a genre work. And that just seems to me to be implausible (amongst other reasons: genres are conventional, at least in part, so a genre doesn’t exist sui generis, but has to wait for us to have made sufficient and appropriate creative and classificatory moves).

Nathaniel:

The first move I would make in response to your comment is to just reject the “formal or genre” dichotomy you implicitly offer. I think there are lots of other relevant factors that we can take into consideration in addition to the conventions that underly genre categories and formal properties of works themselves. Some of these (art world or comic world reaction, history of production, authorial intention, etc.) are already touched upon in the original post, others (e.g. participatory interpretational and classificatory activities on the part of audiences – a particular favorite of mine) aren’t.

My real worry here is that the notion of genre is being stretched so widely as to become too thin to do any serious theoretical work. If all judgements regarding the classification of artworks are genre-based (as Noah comes near to suggesting), then why introduce the new concept ‘genre’ in the first place? It doesn’t seem to draw any new distinctions (which I take it was part of the original purpose of the notion, and the attention lavished on it – to distinguish those works that are generic from those that are not, as well as to distinguish between works within different genres).

One last thing worth noting (I am not, in this bit, implying either approval or disapproval of the following practice – just noting its existence for further thought): Some scholars would say that we can distinguish between 50 Shades of Gray and The Trial in terms of the fact that the former is a genre work, and the latter is not. But this sort of approach (which I am not necessarily saying is right) implies that many works do not fall into genres (typically, on such approaches, it is the ‘high’, ‘fine’, ‘good’, or at least non-‘popular’ works that are non-generic).

Yeah…I think the use of “genre” as a classification to separate non genre work from genre work is largely pernicious, poorly thought through, and used mostly to claim status. I think it’s much more useful to just acknowledge that, yes, all artwork is a genre, and belongs to multiple genres. You can certainly separate genres from one another in various ways, but the idea that certain works are formula bound over here and others aren’t over there; I don’t think that’s true, and I’d just as soon do away with it.

Thanks for pulling me up on that false dichotomy, I do still think it is useful to consider the genre of Art, perhaps not all art is appropriate to be categorized by genre as some work is too specific, but I do think that at least in the practical application of genre (filtering what people see, classifying according to its use of styles, and grouping work by type) the term genre is appropriate for a large proportion of “high” art, there are conventions and tropes in that work and they are marketed, or at least distributed, in the terms of genre. By that I mean even if you were to argue that the “high” art world was without genre conventions (which I would not believe), then even the effect of classifying it all together as “high art” has the same practical effect, for the audience/consumer, as applying a genre label to it.

Genre’s not exactly a new term, historical painting is a genre of painting, and comedies and tragedies are genres of plays, and they’re about as old as you can get. Unless you’re only using the term genre to describe pulp or pop culture genre work in relation to high art I don’t think it can become too broad, because the word demands further categorization by definition.

I acknowledge the existence of work that does not fit into a traditional genre (or at least not naturally) but even then that work is still placed in the quasi-genre of avant garde or experimental, I just don’t think you can escape genre if you make any media, because it is impossible to remove something from its history and because people demand definition.

I also agree with Noah that there is often an attempt to use genre vs fine art as status grabbing, I do not believe that there is a significant difference between saying someone works in a “tradition of formalist abstraction” (as I’ve seen on plenty of artists statements) to saying someone works in the genre of wildlife photography. If there is a distinction that distinction comes from the modern reaction against pulp rather than anything objective, so far as I can see at least.

I agree that often the use of genre versus non-genre, as I described in the final bit of the last comment, is an attempt at status-grabbing. What I am not convinced of, however, is that it has to be. It just seems possible to me that someone could create a work of art W that didn’t fall into any pre-existing genre, and that, further, didn’t automatically ‘create’ a new, singly-instanced genre “of the same type as W”. If that’s all that’s required for the existence of a genre, then every created object is in a trivial one-member genre, and the notion is trivial.

Part of the question at issue, of course, is what sort of category a genre is. I think that genres are a particular type of category (determined in part by various conventions adopted by audiences regarding the type of interpretational moves that are appropriately mobilized when experiencing works in a particular genre). Art forms are (I think) a different sort of category (with different kinds of determining factors – in particular, two works falling in the same art form seems to involve – amongst other things, perhaps – the fact that they can and should be compared and contrasted to each other in appropriate ways). Media are, again, another, different, sort of category (whether or not an object is an instance of a particular medium, I suspect, is determined much more in terms of formal properties than are analogous categorizations with respect to genre or art form). And the class of artworks is another type of category (contrasted most obviously with the non-artworks) with another, different set of determining conditions.

Of course, to defend all of this as correct, I would need precise, well-worked out accounts of exactly what the relevant criteria are for each of these different types of classificatory taxonomies. And of course, I don’t have that – just the loose intuitions partially worked out in terms of the hints above, and a conviction that we probably wouldn’t have developed these different theoretical concepts unless they were playing distinct theoretical roles.

It is worth noting that the existence of works that are in the same genre, but in different media, and different art forms, seems uncontroversial: a film and a novel can both be instances of the same genre – say, WESTERN – but are clearly works in different media, and different art forms.

(Of course, I realize that many of you will say that the film and novel share some genre classifications – in particular, they are both in the WESTERN genre – and don’t share others – in particular, one is in the FILM genre (but not the NOVEL genre), while the other is in the NOVEL genre (but not the FILM genre). But that seems to do a lot of violence to the way we talk about these things, both theoretically and ‘on the street’, so to speak.

” It just seems possible to me that someone could create a work of art W that didn’t fall into any pre-existing genre, and that, further, didn’t automatically ‘create’ a new, singly-instanced genre “of the same type as W”. ”

It doesn’t seem possible to me. How would the production of this come about? Can you point to it ever happening, anywhere, in the history of the world? I’m pretty sure you can’t. Art is in conversation with other art, just about always. Occasionally you get outsider artists like Henry Darger I suppose — but of course he’s nicely contained in the genre of outsider art, like I just said. Even not belonging is belonging. Art just is not a spontaneous generation; it can’t be. If it doesn’t fit into a genre of art, it isn’t recognized as art. Eventually, a genre may develop to contain it and then it can be perceived retroactively as art. But the idea that you could have art without the genre markers of art is an impossibility. You recognize art by its genre; otherwise you have a laundry list or some such.

The idea that you should only compare works in certain genre or mediums seems like it’s a good argument against seeing those categories as especially important. There’s no reason not to compare film to comics or comics to prose or prose to jazz or what have you. There will be similarities and differences, just as in any comparison of two works of art.

And yes, something like a Western crosses mediums. But I’d say comics can cross mediums too (there’s Roy Lichenstein, after all.) It’s just different ways of grouping things, based on historical and social conventions. Why shouldn’t film and television be the same medium, especially with the internet and streaming being what it is?

A second thought — consider this principle “If the identity-conditions for a concept are of such-and-such a kind, then the identity conditions for its subordinate concepts are likewise of such-and-such a kind”.

This seems like a reasonable assumption, at least prima facie, when we’re dealing with directly subordinate concepts (I mean when they’re the next level down in generality, as it were — e.g. (biological) species to genus). If the concept METAL is cashed out as a Kripkean natural kind, it seems reasonable to infer that that should work for the concept GOLD; if NUMBER is defined by formal properties, so too is EVEN NUMBER, etc. The principle certainly isn’t true universally, but it looks to me like a useful heuristic.

If that’s right, then the onus isn’t on the COMIC-definer to justify using the same kind of moves as have been made by the ART-definer. Rather, the onus is on somebody who thinks that that is the wrong approach.

Or, to put it another way, it is possible that “we could be convinced that there is an adequate definition of comics, but also convinced that such a definition should look very different from extant attempts at defining art”, just like it’s possible that my right arm is in fact (unlike the rest of me) made of green cheese. But the burden of proof cannot lie with denying every mere possibility, or we’d never get started on the road of inquiry; we’d never even make it out of bed.

Of course, the problem with the burden of proof is that it’s always on the other guy…

FWIW, Roy, every time I hear Noah say “genre”, I reach for my revolver.

” Art is in conversation with other art, just about always. – See more at: https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2015/01/why-is-comic-studies-so-predictable/#comment-165596Occasionally you get outsider artists like Henry Darger I suppose — but of course he’s nicely contained in the genre of outsider art”

Darger was influenced by L. Frank Baum and apparently references Baum in his novel, and his similarities with “insider artists” like Baum or Lewis Carroll is something I personally find rather creepy. You could probably classify him as a fantasy writer.

Roy, your qualms with Noah’s position seem to centre on his use of the already loaded and overworked term, ‘genre’. If you were substitute something like ‘conceptual category’, ‘overarching structure’, ‘some implicitly recognized minimum degree of shared elements or charcteristics’, or the like, I think many of your objections would fall away.

Also, I would suggest that the concepts ‘art’ and ‘comics’ are logically or structurally similar not simply by dint of referring to some creative output typically consumed by others, and not just because one may be a subset of the other, but also because they are super-genres or broad conceptual categories into which many works from many eras may fall.

I want to add “genre” to my above list of difficult to define words. As a longtime reader of this site, I can’t believe I missed it before.

Roy – Your second comment is precisely why I think it is useful to think of Art as a genre, they both rely on conventions around how we consume them to define how we categorize them. As you said;

“(genre is) determined in part by various conventions adopted by audiences regarding the type of interpretational moves that are appropriately mobilized when experiencing works in a particular genre”

this sounds exactly like a lot of theories around preparing yourself to be open to an “art” experience, if the genre label prepares us to interpret in a specific way, and then so too Art label prepares us to interpret in a specific way. To me this sounds like a very similar kind of classification, both in their purpose and conceptual process, so similar in fact, that I am not convinced that Art can not just be a subset of genre if genre as genre is such a broad term.

Though perhaps Travis, John, and Jones are correct, genre may be too loaded a term, perhaps a different kind of word should be used to describe this sort of classification.

There’s a lot here, but I’ll try to be brief, and put the thoughts into some sort of logical order.

Tavis: I think you are right – if we replace “genre” with “conceptual category” then a lost of my direct worries fall away. But I think we need the notion of genre (and other concepts that are more specific – that pick out certain kinds of conceptual category). Why? Well, for one thing, I think that different kinds of conceptual categories are determined by different kinds of criteria, and some of the more fine-grained notions we have formulated (like genre) track particular kinds of criteria. And this brings us to:

Jones: The “If a superordinate concept is determined by criteria of such-and-such kind, then subordinate concepts are determined by the same sort of criteria” principle isn’t just “not true universally” – it seems to me to have more counterexamples than not, and just isn’t even a “useful heuristic” (thus I see no reason to lay the burden of proof on someone who denies this).

Some immediate counterexamples:

Automobile is determined primarily functionally, Dodge (or Mercedes, or Buick) purely legally.

House is determined primarily functionally, brownstone, or split-leve ranch, mostly formally (and maybe partially historically).

Comic is not determined primarily formally, but comic formats (comic strip, floppy, trade paperback, etc.) are*

*[Graphic novel might be a format – if its a format at all – that is determined in ways similar to the concept comic. This doesn’t affect the more general point.]

As a result, the argument for thinking genres are determined in the same way as the overarching category art fails (and lacking any other argument for this claim), we seem free to at least explore the possibility that they aren’t determined in the same or similar ways.

Noah: And this brings us to my reasons for thinking that there could be a work that didn’t fit into any genre. Given that I think genre is a particular type of conceptual category, with a particular kind of determining condition, which might be different from the kind of condition involved in other artistically relevant conceptual categories such as artwork, art form, medium, movement, style, etc., whether or not there could be an artwork that wasn’t a genre work is an interesting open question.

The work in question could, in fact, be easily identifiable as an artwork (within an art form, perhaps even within a particular movement or style) without being contained in any existing genre by satisfying the determining conditions for the former without satisfying the (presumably significantly different in kind) determining conditions for any of the latter (i.e any particular genre).

I think your objection will be that these other categories just are genres. But I think I have made it clear why I prefer not to use the term in such a wide-ranging way (and, to be honest, this understanding would have been taken to be rather odd and theoretically perverseuntil roughly Mittell 2004*).

*[While there is much of value in Mittell’s work on genre, the whole “genre is cool, so let’s make every cultural category a genre” bit of the approach has, I think, been a rather pernicious influence on genre theory.]

Noah: I never meant to imply that you should only compare works that are in the same art form, or the same genre (this is my fault – I wasn’t all that clear). Rather, the point is that art forms (and I think genres) might mark the delineations for what objects should be compared when making certain sorts of evaluative claims. For example, when judging whether a particular painting is dynamic, other paintings (i.e. members of the same art form) are the relevant comparison class, not other artworks: it would be insane to criticize a painting because it wasn’t as dynamic as most dance works, but it is perfectly reasonable to criticize it (with respect to its dynamism, in contexts where dynamism is a good-making feature) because it is less dynamic that other paintings. (And I suspect similar things could be said about genre).

I like Mittell quite a bit.

If you can come up with an artwork that doesn’t fit into any genre, go ahead. I can’t think of any.

Oh, and I don’t see why you couldn’t compare dynamism in artwork and dance. Why not?

ha, fair enough, Roy.

…that said, could you at least gesture in the direction of a sketch of a promissory note for what a better strategy for characterizing comics might look like? Do you have anything particular in mind?