This was originally posted on The Middle Spaces.

_________

When I discovered Weird Love #3 on the shelf at my usual comics joint, I didn’t hesitate to pick it up. I may still spend most of my comics dollars on superheroes, but I always look through the indie shelves for stuff to try out. Truth is, when it comes to indie comics I am much more likely to wait for the trade collecting individual issues, while there is something about the serialized nature of the Big Two comics that is part of their appeal to me. I know this is probably backwards since indie presses (when they’re really “indie”) could probably use my monthly money while I am just another sucker to Marvel and DC, but it is what it is. Let’s hope that my buying Weird Love when it comes out every other month is doing a part in keeping it around.

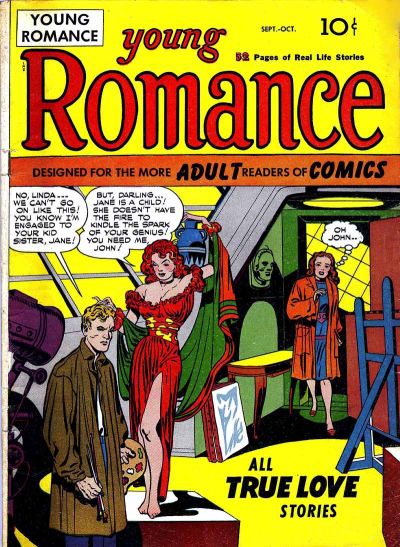

Anyway, I knew nothing about Weird Love, but I imagined (and hoped beyond hope) that it was some transgressive re-imagining of the romance comic genre, but what I found turned out to be even better. Instead, it was refurbished reprintings of rare romance comic stories from the 1950s and 60s. From a genre that—according to Michelle Nolan’s Love on the Racks: The History of American Romance Comics—once boasted over 140 different romance titles being published at once, editors Craig Yoe and Clizia Gussoni chose the strangest of them and delicately re-furbish the art from copies (since in most cases the original art is long gone). Upon reading the stories in Weird Love #3 (and the ones in issues #4 and #5, as well), I started to get the impression that what made them “weird” was not their transgressive aspects (if any), but the dissonance between their rigid adherence to idealized depictions of heteronormativity and the contemporary moment’s shifting social mores. What the stories in Weird Love soon made clear to me—and I went and sought out some of the classics of the genre in the form of reprints of Jack Kirby and Joe Simon’s Young Romance for confirmation—was that the heteronormative values these romance comics reinforce are really friggin’ queer. I don’t say queer to mean homosexual, as in the political and pejorative usages, but I mean strange. I mean, not adhering to the categories of “normal.”

That the ideal depictions of sexuality and heterosexual relations could change so dramatically in the last 5 or 6 decades underscores the socially constructed nature of sex and gender, the fluidity of what appear to be their ahistorical categories, and the inextricability of “normalcy” from adherence to social codes based on the simultaneous (in)visibility of sex that, in the words of Michael Warner in the introduction of Fear of a Queer Planet, “testifies to the depth of the culture’s assurance (read: insistence) that humanity and heterosexuality are synonymous.” (And I would add, white heterosexuality, but sexuality and race intersect in complex ways, beyond a simple blog post, so if I don’t get back to it, don’t think I forgot or didn’t think of it.) That the assumptions embedded in the stories were once (and to some cases still are to varying degrees) normative shows how strange heterosexuality really is.

For example, Weird Love #5 includes a story entitled, “Thrill Crazy” (which originally appeared in Love Journal #11 from December 1951), in which Marsha’s desire to be popular leads her to drink alcohol and end up at a “necking party,” whose “unwholesomeness” made her “feel ashamed and unclean!” She witnesses her friend have a breakdown from the anxiety of running with that teen gang, and nearly succumbs to that fate herself. Lucky for her, in the end a “worthy man”—a hardworking local boy who warns that no good will come of the company she keeps and comes to her rescue on the night of the necking party—deigns to love her despite her having gone astray. In the end she learns that “just going to a movie” with him is an appropriate amount of excitement, and a lot safer for her virtue. These stories are knots of sexual contradiction. This is what I mean by the simultaneous visibility and invisibility of sex: the stories can only allude to and cannot ever name feminine desire for sex, but their built on that desire and the resistance to it that virtue demands. The customs around heterosexual cultural practice are weird and sometimes even destructive, and the heterosexist assumptions that inform them harm straight people, too.

Consider, the Edith sub-plot in the most recent season of Downton Abbey. She has to hide away her child, because otherwise people would know that she had had sex before marriage with a man she planned to marry! It would ruin her and devastate her family! It is absurd, of course—especially when looked at in light of Edith’s pain at being separated from her child who may never know her. (That a family of what is essentially the peasant class, has to take in the aristocrat child is something else entirely—gendered class exploitation). Everyone knows that people have sex and that sometimes (often) have it before being married, and yet it must remain invisible, despite underwriting our relationships and our very existences. In the era of the TV show, to say it is present invites condemnation. This is not to say that women are not still shamed and scorned to varying degrees for having children out of wedlock, but there is much much less insistence to pretend at “normalcy”—a curbed sexual desire equated with moral character—to the degree that you’d deny the very existence of your child. Still, none of the romance comic stories I have been reading would dare include such a racy topic as the unwed mother.

Instead, Weird Love #4 reprints the incredibly titled story, “Too Fat to Frug.” I can only assume the play on frug (to suggest “fuck”) was lost on the censor board because this comic has the Comics Code seal on it. In it, sexy go-go dancer Sharon’s inability to control her jealousy drives her man away and leads her to the kind of emotional overeating that “disturb[s]” her “glands” making her permanently fat, losing her dancing gig and the ability to attract any men of quality. “Luckily” for her, a nice chubby guy takes a shine to her, leading to the moral: Even fatties can find love. I mean, I think that is what I am supposed to take from it. Sure, one could read it as a positive body image supporting story, except that her fate is clearly cast as tragic. She’s a loser who has to make the best of her own failure. The story’s less obvious, but no less present, lesson is that if Sharon had learned to control her emotions and not second-guess her man’s ogling another woman, she might not have suffered her embarrassing fatness.

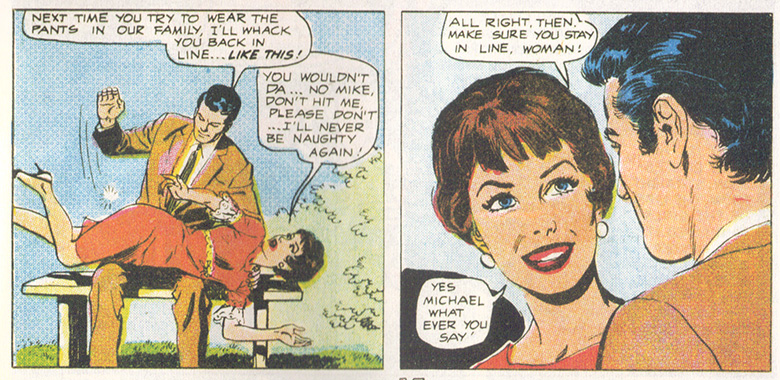

Another of my favorite Weird Love stories is, “You’re Fired, Darling” where Doris the office manager is forced to fire her boyfriend, Mike, who is terrible at his job. Despite his anger, he eventually comes to realize what she already knew, that he was a lot more suited to physical labor and working on a construction crew with his uncle, so he comes back to her—but makes sure to give her a spanking to teach her a lesson her for trying to “wear the pants.” In the end, she expresses her relief to have Mike be “masterful” and take charge, so she doesn’t have to be in the anxious and “unnatural” position she was in as his boss. This kind of submissiveness—for which the women are grateful—is a common conclusion to these stories. Looking back from 2015 this idealizing of such submissiveness becomes a kind of peculiar fetish. The fact that this is normal desire is precisely what seems so strange in the present day.

Throughout these stories women tend to be infantilized, even as the constant reminder to guard their “virtue” reinforces their primary value as sex objects. This is notable in how even young girls are sexualized. They are either dangerously attractive for which they are to be blamed, or pityingly unattractive to the degree that even as a child it is noteworthy how difficult it will be for them to find husbands. The shape of heteronormative romance as traced in these stories is so contradictory and confining, that it is impossible to not imagine the broadly queer possibilities that lie all around it.

Of course, it also bears mentioning that the vast majority of these stories (if not all—the credits of these stories are lost in some cases) are written and drawn by men, but written in a confessional first-person, so these male storytellers are ventriloquizing the desires of women and their despair when their unwillingness to conform is punished, showing them the error of straying. Or, if a woman isn’t actually punished then—as in the classic “There’s No Romance in Rock n’ Roll (originally from True Life Romance #3 from 1956) —the protagonist discovers a real mature man whose very presence recasts the her early love, rock n’ roll, into childish noise! So while I call these strange attitudes towards heteronormative love “idealized,” I can’t claim that these attitudes were necessarily shared by women. Instead, they were thought by the male creators to be attitudes their female readership should identify with, both in the desire to rebel and to eventually righteously conform. Over and over again, the rebellious spirit of women is evoked in order to highlight the need for them to be tamed by their relationship with the right man.

The Simon and Kirby stories reprinted in the Young Romance anthology reinforce this and really are no less weird even thought they are not collected under the Weird Love title.

These comics—quoting Michael Warner again— “assert the necessarily and desirably queer nature of the world.” We don’t want to be trapped in static definitions of sexuality and gender, especially given the ways they intersect with all other aspects of life. The love depicted as ideal in these comics occupied a world without race until some Young Romance stories of the 1970s, and to my knowledge, none of them addressed gay love except in the most oblique terms. We need a queer world. A world that leaves room for non-compliance, non-conformity, for forms of loving that not only defy categorization, but break up and smash the categories that can sometimes be hidden within.

&nsp;

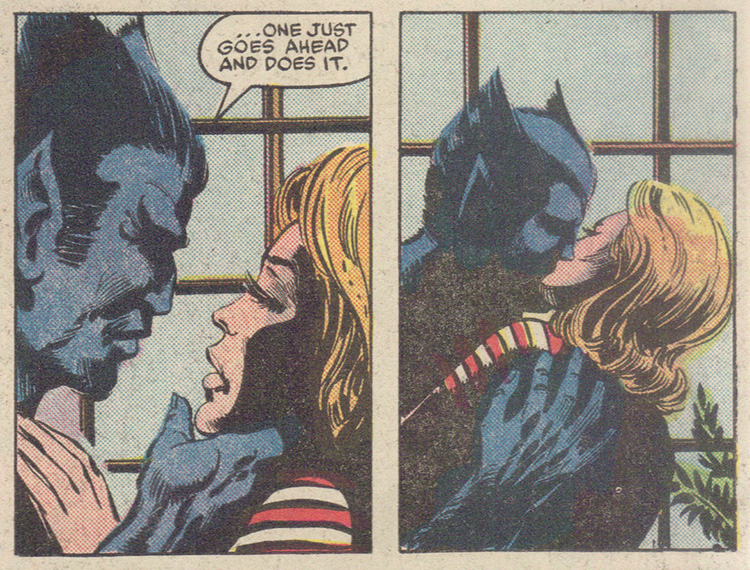

t is easy to see why Lichtenstein was attracted to the isolated panel for his work. (from “Love, Honor and Swing, Baby!” – Just Married #67, October 1969 – and Weird Love #3)

Something I really love about reading these comics is just how nicely individual panels are suited for collected as examples of isolated absurdity that might otherwise go unnoted in so-called “traditional” forms of love. So many times, one weird scene defamiliarizes the heteronormative, making it so strange as to be laughable, worthy of mockery. As each issue of Weird Love comes out, I find myself going to the scanner to capture examples. (And you will occasionally be able to find more examples after this post is live on the We-Are-In-It tumblr).

The history of romance comics has also reinforced for me how the market for comic books has shifted in the past and could continue to shift if the major publishers did not use the industry’s arrested state of development as an excuse for peddling the same old thing. Claims that they must play to the market ignore the relative lack of competition and thus how they shape that very market by what they offer. As comics legend Dick Giordano once explained, by the late 1970s the material in romance comics became too tame for “sophisticated, sexually-liberated women’s libbers” (his use of “women’s libbers” is highly suggestive of what he thought about this change). Feminine desire that matched what women might actually feel and experience could not be written to circumvent the Comics Code Authority at the time. But if that is the case, the question then becomes, now that the CCA is a thing of the past and mainstream comics are full of many things that the censor board once disapproved of, what keeps the Big Two from exploring that market again?

The history of romance comics has also reinforced for me how the market for comic books has shifted in the past and could continue to shift if the major publishers did not use the industry’s arrested state of development as an excuse for peddling the same old thing. Claims that they must play to the market ignore the relative lack of competition and thus how they shape that very market by what they offer. As comics legend Dick Giordano once explained, by the late 1970s the material in romance comics became too tame for “sophisticated, sexually-liberated women’s libbers” (his use of “women’s libbers” is highly suggestive of what he thought about this change). Feminine desire that matched what women might actually feel and experience could not be written to circumvent the Comics Code Authority at the time. But if that is the case, the question then becomes, now that the CCA is a thing of the past and mainstream comics are full of many things that the censor board once disapproved of, what keeps the Big Two from exploring that market again?

The jury is still out about the current state of the comics buying public but signs point to significant and growing numbers of women. Recent announcements by Marvel and DC seem to directly address this realization. But while it seems like the superhero cadre is playing catch up, I wonder if this shift in comics demographic will lead to a shift in the diversity of comic genres themselves. I am not trying to suggest that more women readers will lead to a return of romance comics (though I’d love to see what a modern romance comic might look like), but the fact that DC comics published Young Romance until 1977—not really all that long ago (in my fucking lifetime!)—demonstrates that difficult to imagine changes can happen in a relatively short period of time. I mean, who in the late 50s would have predicted the resurgence of superheroes on the horizon?

Furthermore, there is still a strain of romance influence that entered the superhero genre that can occasionally be seen in the cape and cowl titles. The influence is all over the place; from Superman’s Girlfriend, Lois Lane repeatedly paying for her obsession and schemes, to that splash page from Fantastic Four Annual #6, where Kirby draws the Richards with the radiance of the final “happily-ever after” panel of a romance story. It is probably most clear in the drawing style John Romita Sr brought to Amazing Spider-Man when he took over for Ditko in 1966. There are even characters that still survive from the romance days. Patsy Walker, Marvel’s Hellcat, started out as a teen romance comic character, and when Marvel’s predecessor Timely Comics was cutting back on all their titles in the late 50s, Patsy’s three titles were still selling at phenomenal levels. I do not think it is overstating the case to say that Patsy Walker may be the most important character in the Marvel Universe, because without her success there may have been no comics division for Stan Lee and Jack Kirby to transform into what we know as Marvel Comics.

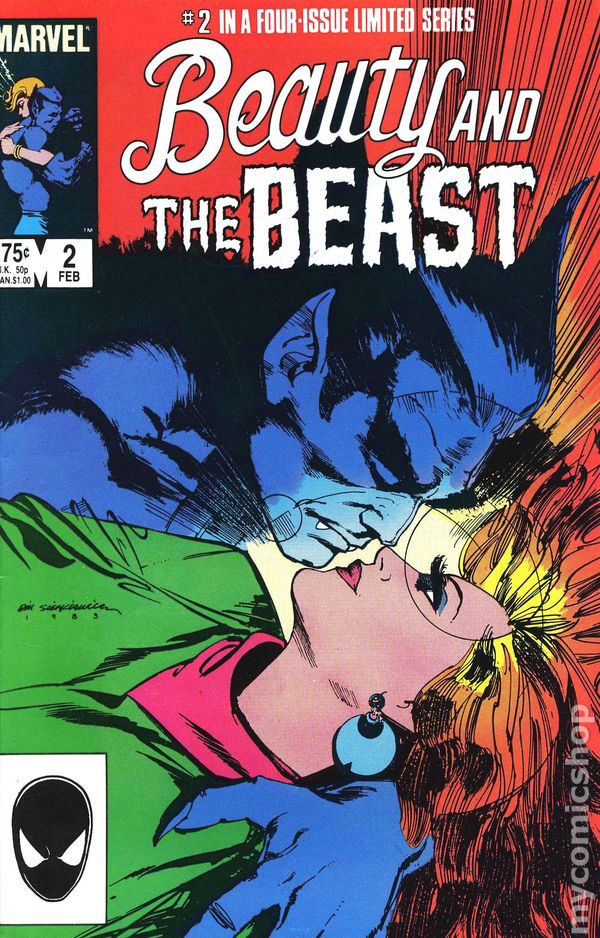

Bill Sienkiewicz’s cover for issue #2 definitely calls to the romance genre.

Another example of this influence is Jeff Loeb and Tim Sale’s Spider-Man: Blue from 2002-03 which focuses on the shadow the death of Gwen Stacy casts on Peter Parker’s marriage to Mary Jane.

But perhaps the best example is Ann Nocenti’s 1984 limited series Beauty & the Beast. The Dazzler-focused series especially strikes me as the kind that really could have indulged the freakier side of the superhero concept, but then again I was also very upset when Grant Morrison walked back Beast’s admission of sexual confusion. I long ago imagined him into a long-term “open secret” type gay relationship with Wonder Man, so his queer possibilities were a part of my understanding of the character since about age 10.

Beast acting beastly in Beauty and the Beast #2

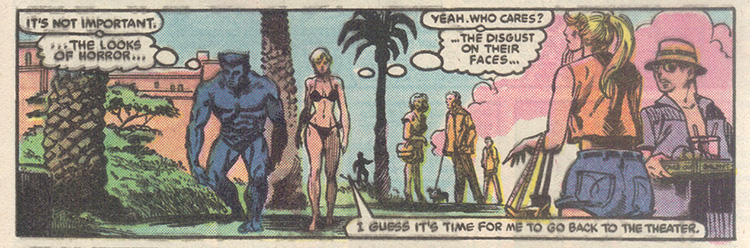

The first issue in particular has a structure that seems to pay homage to the romance comic stories of old. In it, Alison Blaire, the Dazzler, has been recently outed as a mutant, leading her to hang out with shady characters that party every day of the week in pursuit of revitalizing her career, further ruining her already ruined reputation. A full page montage covers the common romance comic trope of her indulgence and resulting indignity. The Beast, Hank McCoy, former X-Man and Avenger, fills the role of the love interest, acting as impulsively aggressive and entitled to Dazzler’s attention as any romance comic Romeo. The putative hero’s jerkiness is justified by the female protagonist’s straying. Wonder Man has a guest appearance in order to impugn Alison’s virtue and declare her lacking “self-respect.” Despite these problems, to me, Beauty and the Beast succeeds at doing what X-Men comics have long tried to do, make effective use of the mutant metaphor—not as a stand in for race or queer sexualities, but as stand in for the strangeness of these characters themselves, for the queerness possible within a cisgendered heteronormative framework. What is Beast if not a furry’s dream? How else are we to interpret the vicious whispers of strangers that see them together in public and judge them as immoral and disgusting, if not as a sign of the strangling confines of “the normal?”

Hank and Alison feel disapproval for their relationship wherever they go. (from Beauty and the Beast #3).

The Beauty and the Beast limited series (which, by the way, Rachel and Miles X-Plain the X-Men covered in episode 35: “Post-Disco Panic” of their awesome podcast) is very unevenly written and drawn, but highlights a line of force, a thread sewn through from the strange kinds of stories found in IDW’s Weird Love series to the bizarre relationships in a world of rock people, shape-changers, elastic men and invisible women. I think the world is ready for a romance-themed superhero comic. There has been some attempts at this (like 2009’s Marvel Divas, which, like the old romance comics was written and drawn by dudes and which I’ve only ever heard bad things about), but imagine a title given even a tenth of the kind of support bullshit like Age of Ultron or Axis crossover events gets. One can dream, I guess.

I am going to continue to delve into my new obsession. I think these old stories despite their frequent patriarchal foundations are important, not only because of their commonly beautiful art and storytelling, but also because they serve as a reminder of how strange the once most-accepted norms really are.

“though I’d love to see what a modern romance comic might look like”

I don’t know if you have any interest in manga, but a substantial fraction of shoujo (girls’) and josei (women’s) manga focus on romantic relationships, in varying degrees of explicitness (as do a large proportion of boys’ and men’s manga, for that matter). There are also a large number of manga adaptations of older Harlequin romances, which are a hilarious blend of the two genre’s narrative/aesthetic conventions (check out Amazon’s Kindle books section for these).

My personal favorite of the adult-female targeted romance manga available in English is “Tramps Like Us”, which is sadly long out of print but may be available from libraries with large manga sections. For a more recent and readily available series, with bonus sexy vampires, you could try “Midnight Secretary”. If you are interested in ladies’ smutty heterosexual manga, check the Amazon Kindle store for “teens love” or TL (which doesn’t necessarily involve teens).

Among teen-girl titles, “Say I Love You” is at the more realistic, serious end, whereas something like “My Love Story” is at the goofball rom-com end. Personally, I prefer the more gender-bendy stuff, like “Otomen” (boy who looks butch but has a feminine personality falls for a girl who looks feminine but has a butch personality), the also out-of-print-so-check-your-library “Afterschool Nightmare” (psychological horror with a fat whack of gender dysphoria, gender anxiety, and bisexual love triangles), or any of the dozens of “tall princely girl falls for hot crossdressing boy” titles (of which the best, “Usotsuki Lily”, is sadly not available in English).

Thanks, JRB.

As is sadly typical, I have flagrantly demonstrated my American/Western bias in that bit of my post. . . At some point I meant to add a line like “I know there are a ton of Japanese comics in this (and mixed) genres, but I am not (as-of-yet) familiar with them.”

“I have flagrantly demonstrated my American/Western bias in that bit of my post”

No problem. I’m almost totally ignorant of superheroes, and Marvel / DC in general, myself. :)

“No problem. I’m almost totally ignorant of superheroes, and Marvel / DC in general, myself. :)”

Ignorance doesn’t come much more blissful than that…

Have you seen Ranma 1/2, Osvaldo? Might be interesting in terms of your ideas about the queerness of heterosexual romance. It’s a het rom com/screwball comedy where everybody undergoes body transformation when they’re splashed with water (Ranma turns into a girl; his dad turns into a panda bear, etc.)

Simon and Kirby present a good case study; they did so much work in romance *and* other genres that you can easily compare the tropes for “boy” comics with those for “girl” comics. And the comparison is not a happy one — actually, it’s flat-out depressing how practically every single one of their romance stories revolves around the female protagonist repudiating the most distinctive (and therefore most unsettling to the patriarchal status quo) features of their personality and behaviour. Even when their stories don’t conform to this model, they generally feature the woman being punished with an unhappy ending because she *fails* to make the required sacrifice. By contrast, the male protagonists of their sci-fi/adventure stories routinely get to overcome some external obstacle or foe.

On the other hand, is that quasi-bildungsroman structure not a standard aspect of the romance genre? I mean, that’s kind of how Emma works, and Pride and Prejudice to an extent (but it’s leavened there by the fact that Darcy too has to learn not to be such a fucking prick)…Noah, you’re into romance; how common is that trope?

Well, I’ve read some romance novels…I’d say that romance for women pretty much never is not generally about how women need to give up their distinctive selves and conform to patriarchy. There is often negotiation with patriarchy, or thinking through how you fit into patriarchy, but the solution is very rarely (never?) outright capitulation or rejection of distinctive selves.

In Kathleen Gilles Seidel’s “Again”, for example, the main character is a soap opera writer. The book is about her professional success in part, and about how she needs to overcome her relationship/family issues in order to pursue that success. She certainly doesn’t give up her job for her man (an actor); in fact, part of what he finds exciting/interesting about her is her professional success, and the way she writes him into his part.

Hmm. Could some of that be due to the different markets — mid-century girls v. post-feminist women?

<3 !

It’s probably because romance novels and shoujo manga are mostly written by women, no?

oh hell yeah, subdee, but then the issue transfers from artist to audience — not “why did these guys do this damn plot all the damn time?” but “why did their audience buy this damn plot all the damn time?”

How sure are we of who was buying the romance comics? I don’t think there were demographic studies…? Do we even know that they sold especially well?

I see the covers that Nick Cardy, Jay Scott Pike, and others were doing for DC romance titles in the late ’60s and early ’70s, and I’d like to think I’d have bought them. Gorgeous art. Luis Avila wasn’t strong at figure drawing, but the covers he did for the Charlton romance books were pretty striking, too.

Noah, they sold really well – like hundreds of thousands of copies per issue – check out Michelle Nolan’s book which I reference above.

Also, I realized after I wrote this that I should have mentioned the romance-type novels Marvel put out not that long ago focused on She-Hulk and Rogue. Anyone read those?

Osvaldo, there were romance novels starring Mary Jane Watson recently, too. I never read them, but I liked the concept.

I think romance novels set in Great Britain’s Regency period commonly use “the wicked rake redeemed by the love of a virtuous woman” as their theme. For that matter, so do Guys & Dolls and a lot of modern teen romance. Aren’t the plots Osvaldo cites just gender-flipped versions of that? Maybe the progressivism of romance comics is that the women finally got to be the worldly sophisticates in need of redemption?