Last week I wrote a short post about Static Shock in which I argued that the book was mediocre genre product, but that at least it was mediocre genre product that made a gesture at diversity. Better non-racist mediocrity than racist mediocrity, I argued.

I still think that’s more or less the case…but is Static really not racist? It does have a black hero, definitely — but then, there are the black villains.

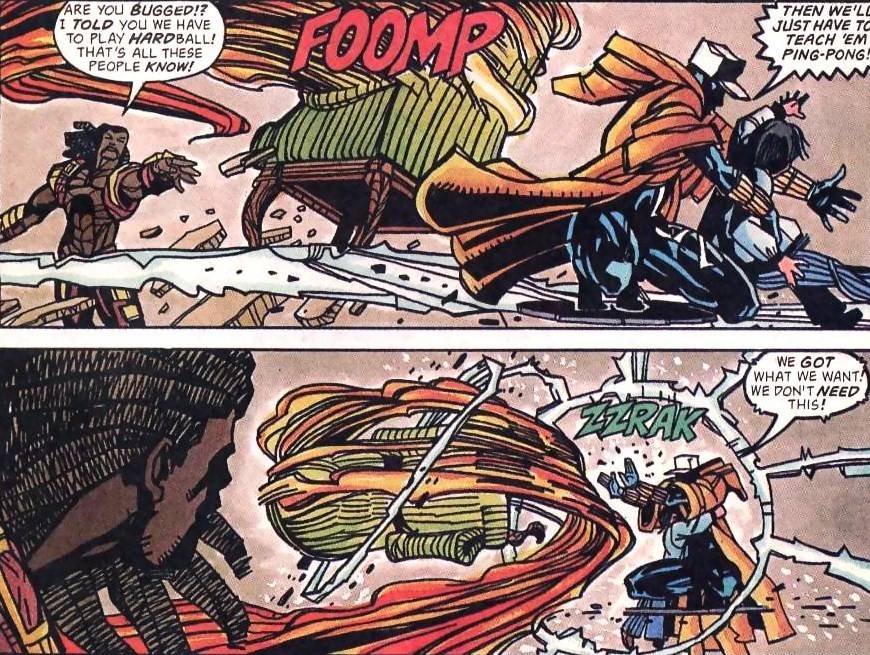

In particular, there’s Holocaust, the evil mastermind behind the first arc. Holocaust is a gangster, but he’s not just a gangster. He’s a gangster with a racial grievance. He tells Static that the hero is insufficiently appreciated. He adds that those on top in the world got there by “luck” — and not just luck, but privilege. “It’s connections. Who you know. Who your daddy knows. It’s birthright.”

But Holocaust, again, is the bad guy. His critique is part of his evilnness. The equality he wants is the opportunity to get cut in on the business of the Mafia; his vision of social justice is equality in the criminal underworld. He’s essentially a right-wing caricature of civil rights advocates; Al Sharpton as brutish, deceitful thug. When Holocaust starts to kill people, Static sees him for what he is, and abandons his evil advisor to return to his superheroic independent battle for law and order. The possibility that law and order might itself be part of a structural inequity is carefully kicked to the curb, revealed to be the seductive philosophy of an untrustworthy supervillain.

You couldn’t ask for a much clearer illustration of J. Lamb’s argument that the superhero genre is at its core anti-black, and that it therefore co-opts efforts at token diversity. The genre default is for law and order. Law and order, in the world outside superhero comics, is inextricable from America’s prison industrial complex and the conflation of black resistance struggles with black criminality. Static, a black hero, is defined as a “hero” only when he aligns himself with the white supremacist vision that sees structural critique as a cynical ruse.

I think it is possible for superhero comics to push back against that vision of heroism to some degree. Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol does in some ways, for example. But Static is hampered by its indifferent quality; it’s not interested, willing, or able to rethink or challenge basic genre pleasures or narratives. Notwithstanding a patina of diversity, it seems like a superhero comic really does need to be better than mediocre if it’s going to provide a meaningful challenge to super-racism.

I re-read this this week during the whole discussion from the previous Static article, and I caught how the critique of structural inequality stopped once Holocaust started tho threaten the guy’s family.

I agree that if the work is going to introduce into its text subject matter like how racism works all over in our society, it should be more mindful to not use it as a talking point from a super villain. I’m still suggesting to read Icon, but this also reminds me of John Stewart’s first appearance in Green Lantern/Green Arrow. His first mission was routing out a racist senator’s plot to incite a race riot, but the character didn’t appear for over a year after that, and it would be ten years before he appeared regularly.

Imagining that McDuffie knew that mainstream comic readers/white comic readers would get behind Static if he went full-stop at the idea of killing someone, like he did in his origin, but further critique of structural inequality would have been nice. I’ve not read many other Milestone comics other than the trades DC put out, but I’d be interested to see Icon and Holocaust have this debate should they cross over.

Magneto’s the more famous version, right? He’s the radical anti-racist voice…and a genocidal megalomaniac.

He’s eventually recuperated, in part I guess…it’s always him joining the X-Men pretty much, though, and putting aside his evil ways, rather than a discussion of what it means for marginalized minorities to take as their task the policing of other marginalized minorities.

Yeah…at some point I reach the conclusion of “It’s a comic book”, but when actively dealing with issues like race there never seems to be an end goal in mind when having the discussion.

Of course that’s probably always met with the fear of alienating the ever-growing knee-jerk reaction of white fanboys who would rather abstain the term “racism” from the human language than actually engage in discussion. Like so: http://www.spidermancrawlspace.com/2015/02/21/editorial-enough-with-the-spider-racism-crap/

Hah! Spider-fans are victims because of “One More Day”! Bad fan fiction of your favorite character is just like generations of systemic oppression!

” The genre default is for law and order”

That’s an interesting reading of static, being a Christopher Priest fan I guess I’ll point out Christopher Priest actually did an arc in Black Panther starring a guy named Kasper Cole where the hero is a cop fighting corrupt cops (His reason for having a secret identity as the Panther is he doesn’t want to work for internal affairs, so he has to hide his secret identity by becoming Black Panther so he can target cops without the other cops going after him).

I’d argue the theme is “corruption” thematically- which effects everyone, black or white.

Christopher Priest is a minister and that might effect his outlook- one of the villains in the book “The White Wolf” wants to make a Faustian bargain with Panther and corrupt him, and can be read as a sort of devil figure.

In Priest’s other book, Quantum and Woody, Quantum’s desire to be a superhero and fight for law and order is painted as rather ridiculous, and likely stemming from a subconscious desire to be white. He creates a full body costume and doesn’t want the public to know he’s actually black, and freaks out when a villain calls him the “n” word because he thinks the villain has figured out he’s black. (Turns out the villain just calls everyone the “n” word)

Noah, Donovan — please don’t distract me with links to “One More Day” hate. I’ll pile on the bandwagon and forget my points.

I read J. Lamb’s comment on HU and some of his articles on his own blog. I understood him to say superheroes were inherently white, not inherently anti-black. Superheroes are a power fantasy. White people created them, so they exercised their power against the things that made whites fearful and angry. Initially, that included bellicose dictators, spouse abusers, and mine managers that created unsafe working environments. For some reason (broader appeal to the middle class, ease of writing a plot — I don’t know), that shifted to things like crime, natural disasters, Nazis, and alien invasions. I think what J. Lamb is arguing (and I invite his correction) is that minorities’ power fantasies would fight different targets. And as he points out, white superheroes get away with flouting the law in the name of justice partly because they’re white and therefore less threatening. A black power fantasy fighting exploitation by the majority could easily be seen as threatening.

I’ve enjoyed Osvaldo’s articles on this topic, especially regarding the successes and failures of attempts at black power fantasy, such as Black Lightning.

Also, Noah, your long-running issue with “marginalized minorities…policing other marginalized minorities” is problematic for me. Who would you rather have do it? Should all the cops in black neighborhoods be white? That would seem to create many problems, but solve none. I’m not disputing your points about structural inequalities or the prison system, but I think the marginalized minorities are better served when they participate in their own policing.

This is totally in line with stuff I have been exploring in my writing about comics, like Super Hegemonic Team-up! Spider-Man, Daredevil & “The Death of Jean DeWolfe”, where I argue that plot arc frames our choices in dealing with crime in a way where they are limited to either “trust the system” or “be tough on crime” while appearing to be the full range of possibilities.

The arc also includes an Al Sharpton figure, who serves no purpose to the plot except, it seems to depict the opportunistic nature of “race baiters.”

I’d say that setting up heroism to mean that the ideal heroic minority is someone who arrests and beats up other minorities is pretty problematic.

James Baldwin has a quote about this:

“The poor, of whatever color, do not trust the law and certainly have no reason so, and God knows we didn’t. “If you must call a cop,” we said in those days, “for God’s sake, make sure it’s a white one.” We did not feel that the cops were protecting us, for we knew too much about the reasons for the kinds of crimes committed in the ghetto; but we feared black cops even more than white cops, because the black cop had to work so much harder–on your head–to prove to himself and his colleagues that he was not like all the other niggers.”

That puts a rather bleak construction on Professor Xavier’s activities, I think.

Hey John, thanks!

Considering the exampe of Superman – essentially a first generation continental European immigrant, albeit raised from infancy by native WASPs (though not in the earliest versions of the story) – maybe the basic rule here is that the ability of the superhero genre to accomodate you depends on the willingness of American society to assimilate you.

Yeah…I think assimilation is a major theme in the superhero genre. Again, the X-Men can be seen as a kind of Jewish model minority…

You’re welcome, Osvaldo, and thanks for your work.

Noah, the Baldwin quote makes sense to me, but so does Professor X. People have a natural tendency to categorize and generalize. We use heuristics to simplify a complex world. The problem with that is that it enables prejudice, literally judging before you have evidence.

I remember a conversation with a man I do not consider a racist wherein he was trying to figure out whether the Sunni Muslims were good and the Shi’a were bad, or vice versa. The ummah is complex, and he was struggling for a heuristic. I had to give him the bad news that it wasn’t that simple. That’s the same thing that Professor X is trying to do — complicate people’s generalizations. “Hey, I heard mutants were bad, but that one just saved me.” Same thing with the black cop. Unfortunately, sometimes he ends up proving it “on [their] head,” so — an imperfect technique for a messy, complicated world.

Wow! Unplug for a day, and great conversations pop up!

First, Noah in the post above accurately discusses my gripe with the superhero concept. The superhero concept requires Whiteness to operate; in practice, this creates narratives that are hostile to minority perspectives, even in progressive comic media like Static Shock. Osvaldo may desire ‘social justice superheroes’; I see such creations as an impossible contradiction.

Second, while John is right to suggest that I believe that power fantasies from people of color would fight different targets (and thanks for reading my stuff, by the way!), it’s also clear to me that how those heroic fantasies conflict would change. Take John Stewart, the Green Lantern. I find it utterly silly that a brother with a rechargeable imagination ring would allow unsafe buildings and unproductive men to flood the urban landscape. In an afternoon, the architect could gather building materials, construct decent housing for local residents, seek out and jail every drug pusher, rob every slumlord of his land ownership documents and eradicate all evidence, and renovate all local businesses: free of charge. Stewart could become a one-man enterprise zone (outside of the anti-capitalist land seizures). With that ring, GL could remake the bleak landscapes of The Wire into the manicured cheerfulness of Blackish.

It’s not flashy, it’s not punching Despero in his third eye (I’m not even sure it’s a good idea.), but it would use an extranormal ability to benefit people of color in a way that’s logical from some of their perspectives. Housing discrimination and anemic private investment created the ghettoes where Superman doesn’t fly at night. I suggest that a Black man with extranormal abilities might try to alter the landscape where he and his family likely live with those powers.

You don’t need tights for that, or random unchecked violence. I get that such a narrative would not work for Action Comics, but that says to me that the superhero genre limits its writers through enforced simplicity, past where meaningful diversity can be expressed in sequential art narratives.

So instead of shining a green strobe on the proverbial hood, Stewart hooks up with space chicks and pines over destroyed planets, just like every other White superhero, but in more boring and redundant fashion. Diverse mediocre genre product. At that point, it almost doesn’t matter that superheroes like him often prove their worth to non-Black readers by attacking Black criminals; every aspect of the “Black superhero” reflects White sensibilities and White moralities in blackface, even when the creators try racially progressive concepts, as Milestone proved.

J., thanks for the response and correction. I would be excited to read the comic you’re talking about. I think those kind of solutions would have some unintended negative effects, but reading how Stewart dealt with those and adjusted his approach would be fascinating, at least to me. I think the biggest hindrance to that comicbook existing is the bias toward simple, stop-the-bad-guy storytelling that you, pallas and others have described.

Stopping the bad guys (in stories or the real world) is useful and satisfying, but it doesn’t solve any underlying root causes. Superhero comics occasionally acknowledge that limitation, usually briefly, and then move on. Superheroes are essentially first responders in tights – not diplomats, activists, or social workers.

Green Lantern: Mosaic (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Green_Lantern:_Mosaic) was an exception which, coincidentally, starred John Stewart. It was not the minority power fantasy you’re talking about, but it occasionally addressed racial issues in a direct fashion. More significantly, it constantly addressed racial and sociological issues indirectly, through standard science fiction techniques. Many issues had no real bad guy, just a complex problem that needed to be solved.

Despite strong sales, Mosaic was cancelled early in its run because it didn’t fit DC’s editorial vision. According to its writer, the leadership expected it to fail, so they killed it before it did (http://www.fanzing.com/mag/fanzing39/iview.shtml).

There is great potential to do something like this again. Steve Rogers/Captain America and Superman both have the social capital that comes with being consistently trustworthy, all-American (and okay, extremely white-boy) heroes. But they rarely use that capital to address larger issues, even though both have lamented that beating up super-villains has little lasting effect. Batman has a well-funded foundation to address these issues, but it’s usually only mentioned as a plot device. Black Lightning, as Osvaldo has noted, has credibility not only as a Justice League member, but as a former Olympian, inner-city teacher, and Secretary of Education. Mr. Terrific has a scientific intellect that almost makes him DC’s Reed Richards – and he doesn’t show up on electronic sensors! Think about how much subversive social justice a hero like that could pull off, and the interesting moral dilemmas he would confront, if someone were willing to publish it.

This is something I’ve been thinking about since I read J’s first comments in Noah’s earlier article. I can’t stop wondering what an earnest and well thought-out story about realistic, black, superpowered people in a world very like ours would be. With meaningful development of the options and choices available to such a person or group (between, for example, social subversion [careful and subtle or otherwise], rebellion [legal or social, thoughtful and principled, self-serving, incidental–such as saving a helpless black teen from a police beating or shooting–or some mix thereof], or implicit acceptance of and conformity with de facto white supremacy, privilege, and norms) there’s a lot of potential dramatic, interesting material to be had.

In a way, the rough concept kind of reminds me a little of a pair of stories from The Amazing Adventures of the Escapist vol. 1. ‘Sequestered’ (written by Kevin McCarthy, with art by Kyle Baker) questions just how much the justice system can be trusted, and just how well punching people in the face and then handing them over to the cops really works, albeit in a humorous light. The very next story in the anthology (‘Prison Break’, also written by Kevin McCarthy, drawn this time by Steve Lieber) takes a somewhat more serious tone, as the Escapist breaks into prison to check on a lost contact. In order to thwart a plot to take over his city using guns and convicts, the Escapist (who is rhetorically a freedom fanatic, opposed to chains and prisons) gathers his own group of convicts (though, also “decent men”, according to our hero) and stages a kind of counter-breakout, declaring, “No more chain gang! No more chains of any kind! Are you with me?” But, instead of freeing anyone, he leads his followers right into a police trap. This leads one of the ‘decent men’ to lament, “I looked up to the guy, and he turns out to be a dirty superhero.”

I remember thinking, this is amusing, but there’s a lot more to be explored here. As good as that anthology was, no one carried that idea any further.

The tension between the ideals of freedom (especially as universally opposed to oppresion, suppression, and inequality) with the act of casually beating seeming criminals and handing them gift-wrapped to the police is, in a world like ours or the Escapist’s, readily apparent. The same should be obvious as regards worries about justice for groups who are systemically underprivileged or discriminated against. This seems like furtile ground.

And I wonder to what degree hip-hop and funk address this question. I’m thinking of lyrical and stage personas, costumes, and varied declarations of what amount to often mundane but nevertheless superhuman feats. I’m not sure where they might fall, exactly, within that tradition, but the most explicit superhero raps I can recollect are Deltron 3030, which sometimes addresses racial concerns but is largely an anticapitalist cyberpunk fantasy, and Jimmy Spicer’s ‘Adventures of Super Rhyme’, which coopts traditional white narratives and figures from a black perspective of ’70s club culture. I am curious as to whether or not J. Lamb (or anyone else) believes any of these templates might function as signposts for or indicators of what a black reconception of the superhero might be, and to what extent.

Wrote about one hip hop song and superheroes here.

If any peer reviewed journal ever accepts my article, “Disco Kryptonite: Black Music, Ironic Distance and White Listening Practice” you’ll be able to read some of my work on hip-hop, superheroes and racial identity via “mainstream” reactions to early rap and Jonathan Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude.

First off, growing up the best synthesis of hip hop and superheroes was The Last Emperor’s Secret Wars. Imagine Stan Lee’s creations battling your favorite Marvel franchise heroes, and you get the point.

As for the main question — does hip hop and funk provide template for meaningful diversity among superpowers — my short answer is no. The larger-than-life narratives, costumes, and personas found in hip hop and funk draw parallels with superhero comics; many rappers since the 90’s express their interest in superheroes in their music. The Wu-Tang Clan openly identified themselves as superheroes (Ghostface Killah as the Ironman Tony Stark, Method Man as Johnny Blaze, the Ghost Rider, etc.) and never interrogated what it meant to promote rap music — developed by people of color within the Bronx’s urban dysfunction — by appropriating White male power fantasies marketed primarily to White audiences.

The point? Hip hop (I’m less versed in funk) requires much the same unconsidered patriarchy as superhero comics, for many of the same corporate reasons. Both fields commodify art to market to the same youthful White male demographic, and anti-Black bias and structural misogyny saturate both the industries that generate content and the content itself.

Or put another way, when Ghostface Killah imagines himself as Iron Man, his fantasy requires support for the dubious ethics required from weapons designers, people who apply their engineering and product design skills to innovate death machines. Tony Stark’s fortune was built on the corpses of dead men throughout the globe; his future tech allowed unipolar American military hegemony without the crying eyes of concerned citizens who watch as their sons and brothers and uncles and fathers ship off to war in foreign theaters most Americans cannot spell, much less pronounce. In Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Stark’s helicarrier designs constitute an existential threat to world peace; Stark himself, it seems, had zero concern about pinpoint accurate flying death platforms that enforce American foreign policy globally, an updated take on gunboat diplomacy.

Ghostface Killah’s first ‘solo’ album does not critique any portion of Tony Stark’s characterization or history; if anything, Stark becomes a useful caricature Ghost inhabits to engage the bling rap he and his partner in rhyme Raekwon the Chef pioneered in the mid-90’s. The end result is a Black man who pretends to be a White man on wax so that other Black men can revel in his fantastic and gaudy wealth, amassed without remorse or pity or sorrow from the stacked corpses of dead soldiers and the mass graves replete with unfortunate collateral damage.

Nothing about this dynamic speaks to authentic Black culture or history; there are plenty of wealthy Blacks, and even some billionaires within the darker nation. Hip hop largely rejects those personas because hip hop sells the systemic poverty and feral morality of the inner city corner to the entire world, with special attention to the same young White males that the comic industry seduces with images of wealth, power, prestige, and physical supremacy. If you can imagine yourself Iron Man as a towheaded tweleve-year-old asthmatic, you can imagine yourself Ghostface Killah, and parrot rhymes about crack sales and gold chains to your cousins with the same intensity as you relate the Extremis protocol to your friends.

In both instances, race and gender and class approach fluidity in practice, but prejudice and stereotype and systemic oppression do not. So Tavis, I appreciate the sketch of a possible way forward with superhero diversity, but I reject hip hop and funk as a useful template.

I welcome the debate.

apropos of wu-tang and superheroes: didn’t bill scienkiewicz do the album artwork for rza’s first solo album? if i remember correctly he basically drew bobby digital as cable.

J, you should check out that esquire article I linked which talks about Open Mike Eagle. He’s an alterna hip hop guy; superheroes figure as empowerment for him but it’s a consciously egalitarian empowerment. “My friends are superheroes/None of us has very much money though/they wear the same underwear as billionaires.”

You could see it as wryly critiquing the Wu Tang superrapper image you’re talking about, I think.

My friend read an autobiography by one of the Wu Tang guys (Old Dirty Bastard?) and said there was a chapter about how, after making it as a rap star, this guy seriously embarked on the project of becoming a real-life superhero. Apparently, he spent a lot of money on high-tech equipment for performing super-heroics before he abandoned this idea.

Maybe it was Ghostface trying to become Iron Man.

I do so LOVE this forum. That said, please allow me to school, (said with love) some of y’all on some points. Although Dwayne McDuffie has become the face of Milestone and NO ONE was more Milestone than Dwayne, he did not start Milestone, Denys Cowan did.

Denys came up with the idea and I co-signed the moment he did. This happened while we were walking the floor at Comic Con International back in 1991. Although Christopher Priest rarely gets credit he was Milestone’s first Editor in Chief and designed the now famous Milestone ‘M.’

Denys Cowan, Dwayne McDuffie, Christopher Priest, Derek Dingle and myself are the official ‘co-creators’ of all the core Milestone characters. That’s true but not accurate. Because we owned the company we all had a hand in the creation of the Dayota Universe, just some parts more than others.

I was the lead creator and wrote the Static Shock Universe Bible. Every major character and most secondary characters I created, 99% of which I based and named after family and friends.

So, its safe to say, I can speak with authority as to Static’s purpose as a Black character.

First and foremost Static was created so Black kids could see themselves represented. As a comic book creator, mainstream writer, television producer and educator MY focus has always been to bring out stories to as many Black kids as possible.

I’ve been doing that for over 20 years. Like I said at the start, I love this forum, many well though out points here. But a well thought out point does not make it real.

http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2014/jul/28/comic-con-black-panel-african-american-culture?CMP=share_btn_link

http://www.bleedingcool.com/2015/02/25/too-many-black-superheroes-michael-davis-from-the-edge/

Hey Michael. Thanks so much for commenting! I appreciate hearing your thoughts.

“the most explicit superhero raps I can recollect”

MF Doom, dude. (aka Victor Vaughn)

(Also, there’s probably a bunch of explicitly superhero stuff in nerdcore, but that’s not my scene, and those artists probably tend white anyway — but feel free to school me otherwise, anyone)

…you might think it’s suggestive that Doom modelled himself after a supervillain, rather than a hero

Pingback: Ep. 46 – Batgirl and the Misery of Being a Cassandra Cain Fan | The Battle Beyond Planet X

Pingback: Figures of Empire: On the Impossibility of Superhero Diversity | Snoopy Jenkins