Action Comics No. 1 was the Big Bang of the Golden Age of Comics, the start point for superhero history. Unless you count the actual Big Bang, which was about fourteen billion years earlier. Or, if you favor a different species of evidence, more like six thousand. Genesis 1:2 opens with a black hole: “the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep,” followed by God’s “Let there be light,” the Biblical Big Bang.

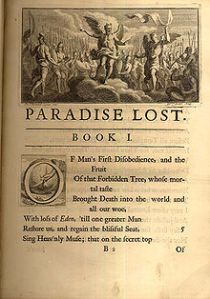

Milton doesn’t give an exact date in Paradise Lost, but he says God created Earth just after booting Satan out of heaven:

There is a place

(If ancient and prophetic fame in Heav’n

Err not) another World, the happy seat

Of some new Race call’d Man, about this time

To be created like to us, though less

In power and excellence, but favour’d more

Of him who rules above;

That’s Beelzebub, one of Satan’s lieutenants, talking. He thinks attacking Earth is a better military strategy that storming Heaven. When Satan flaps across the void to check out God’s latest creation, Milton likens it to the wonder of looking upon “some renown’d Metropolis / With glistering Spires and Pinnacles adorn’d.”

Paradise Lost is basically a superhero comic book, with long slug fests between Lucifer’s League of Fallen Angels and Archangel Michael’s Mighty Avengers. My father remembers hearing the tale from the nuns in his school. He emailed me about that recently:

“Have you ever commented in your writings on what I consider the archetypal superhero plot, one that has its origin in the Bible? I’m referring to the story of archangel Michael being called on to save heaven from being taken over by Lucifer by having a violent confrontation with Lucifer and vanquishing him. This story is so embedded in the western religious psyche that to this day Catholics still pray to St. Michael to ‘defend us in battle’ with Lucifer.”

It’s not the sort of question you might expect from a retired research chemist, but my father only entered the field because he had his brother’s textbooks after his brother became a priest instead. My father’s colleagues were all theoretical physicists, but he preferred working alone in his lab. He said his job was playing Twenty Questions with God. Every day he had time for one: Does it have something to do with . . .

“The reason I think the Michael/Lucifer story is of critical importance is that it injected into the human psyche the concept of the need of an ubermensch (not a collective effort) to defeat evil and save the people. Ever since people are continually looking for such a person, most of the time to their eventual detriment when they believe they have found one. I believe this powerful subconscious longing in the western world for a superhero to save us from evil originated from the Michael/Lucifer story.”

“That’s pretty good, Dad. I hadn’t thought of Michael as the original superhero. I may have to flagrantly steal your insight.”

“I would be delighted if you chose to. An interesting part of the Michael/Lucifer myth is that it is not spelled out in any detail in the Bible. There is only a brief snippet about Michael slaying dragons in Revelation and that’s it – nothing about a great battle between Michael and Lucifer. In the long version, as I learned from the nuns, Lucifer is portrayed as the greatest and most brilliant of the angels. In his great pride, he decides to challenge God as the ruler of heaven. So God dispatches Michael to battle Lucifer, which he does, defeats him and sends him down to the lower regions. (Why an all-powerful God didn’t take on the job himself was never explained.) This long version came down through the centuries strictly through oral tradition. The fact that it has been retold countless times for probably over two thousand years demonstrates, I believe, its powerful grip on the human imagination.”

When I looked up Revelations 12, I couldn’t help imagining how Jack Kirby or Steve Ditko would illustrate the passages. The New Testament author even divides his script into panels. You just need some caption boxes:

[7] And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, [8] And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven. [9] And the great dragon was cast out, that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.

I’d assign Rev. 20 to Neal Adams or Bill Sienkiewicz:

[1] And I saw an angel come down from heaven, having the key of the bottomless pit and a great chain in his hand. [2] And he laid hold on the dragon, that old serpent, which is the Devil, and Satan, and bound him a thousand years, [3] And cast him into the bottomless pit, and shut him up, and set a seal upon him, that he should deceive the nations no more, till the thousand years should be fulfilled: and after that he must be loosed a little season.

Daniel 12:1 makes Michael sounds like a superhero too: “At that time, Michael, the great heavenly prince, the grand defender and guardian of your people, will arise.” Thewarriorprince.us, a website devoted to him, says his “prime duty is to guard and defend the people of God collectively, and those who invoke him individually, from Satan and his demons, as well as their wiles and attacks.” And, according to Milton, those chains he uses on Satan are adamantine, basically Wolverine’s claws. No wonder God made him team leader:

Go Michael of Celestial Armies Prince,

And thou in Military prowess next

Gabriel, lead forth to Battel these my Sons

Invincible, lead forth my armed Saints

By Thousands and by Millions rang’d for fight;

Equal in number to that Godless crew

Rebellious, them with Fire and hostile Arms

Fearless assault, and to the brow of Heav’n

Pursuing drive them out from God and bliss,

Into thir place of punishment, the Gulf

Of Tartarus, which ready opens wide

His fiery Chaos to receave thir fall.

Well, if you want really original, you’d need to talk about Marduk and Tiamat, I think, or at least the version of the war between and angels and fallen angels from Hebrew deuterocanonical texts like the Book of Enoch or the Zoroastrian celestial spirits and their battles.

I think the reason Kirby embraced the Norse gods so much in the Silver Age is because they provided much of the same intrigue, drama and colorful characters as did early Old Testament tracts, but with almost zero chance anyone would take offense (especially in the US) that he was playing directly with the major players of someone’s religion.

Yes, but in the end (for Milton) Michael and the others cannot finish the job. Satan and his minions keep retuning, with tanks (of sorts) and cannons, matching the angels practically stroke for stroke.

The true victory belongs to the Son, who comes in like an action hero and says Stand down, everyone. I’ll take care of this myself, since strength is all they understand. Then he gets crazy — because this time, it’s personal:

So spake the Son, and into terror changed

His countenance too severe to be beheld

And full of wrath bent on his Enemies….

Full soon

Among them he arrived; in his right hand

Grasping ten thousand Thunders, which he sent

Before him, such as in their Souls infixed

Plagues; they, astonished, all resistance lost,

All courage; down their idle weapons dropped.

Excellent piece! I enjoy the notion here provided by the author’s father that the introduction of the ubermensch idea in this story encourages the population to seek out a single action figure to pursue justice/ righteousness. Further, one can easily find parallels with Lucifer in this formulation and modern takes on Sinestro, where beings above human concerns dispatch lesser lights to combat the smartest and greatest of their deputized charges.

My question for the author: do you believe direct connections to Western literature improve the superhero concept’s popularity among an ever more cosmopolitan audience? Should superhero comics make their connections to Christian literature more explicit, like Mark Waid’s Kingdom Come, in an effort to expand readership?

Should overtly evangelical superheroes exist in mainstream comics?

Good questions. Ultimately, I’d say . . . maybe. Or, in the case of Kingdom Come, making the connections explicit is a good idea if the creators feel like it. But (despite Peter’s point about that kick-ass Son above and Jesus’ general demigodness) I’d say the figure of Christ is not superheroic–because he’s not violent. After trouncing the fallen angels, the Son goes on to willingly have himself crucified. Superhero narratives are much closer to Homer, who Milton criticizes for glorifying war.

Cool topic, well told. But the FIRST Superhero was Gilgamesh!

Chris, are you going to write about Birdman ?

I would LOVE to write about Birdman. But that would first require my seeing it. I live in a tiny little town and the Oscar grand-slammer has flown nowhere near us.

There’s a definite superhero moment in Book VI too, where the archangels and the demon armies start throwing whole mountains at each other.

Just like some other folks we know.

And therein lies a question, do these stories predate the epics of Homer or Gilgamesh? Do Beowulf or the Mabinogion take any poonters from the story of Michael? I think the general, non-Hermetic answer to that is ‘no’, but those stories’ heroes all display heroism and superhuman abilities.

*pointers

J., like Chris I think the superhero narrative is in some ways directly opposed to the Christian narrative, and not accidentally either (Nietzsche’s Superman is supposed to be an empowered response to the effete Christ.) Having said that, Christianity in practice (as Milton shows) likes to blast people with power bolts as much as the next religion, so…

Somewhat surprised to see no one has pointed out Kirby actually stated the original Silver Surfer was the fallen angel. Easy to forget after Stan Lee messed up the characterisation, but come on – exiled after defying a supremely powerful being with a big letter G on his chest… how much more obvious can you get?

Sean, perhaps that’s complicated by Surfer sacrificing himself for humanity (and later battling devils).

Well, I was just relaying the man’s own reported comment, but… who knows what went on in Jack Kirby’s head? Maybe he was some sort of dualist or something.

Better yet, maybe he was a closet Crowleyite – that would explain why Dr Doom is basically Whiteside Parsons:)

I like the idea that Doom is Parsons. By that reasoning, Reed is Crowley and Namor is L. Ron Hubbard, no?

Nate A – Hadn’t thought of that. Nice one. Funny – came up with the Doom as Parsons in conversation with a friend a while back, but it was only later we found out Parsons first name on his birth certificate was Marvel. That Kirby, eh?

Great piece as usual, Chris. My thanks to your dad. The comments were also very educational. I think I’d heard of Parsons’ rocketry work at some point, but I spent some time last night reading the rest of the story — fascinating. Just to continue the comic parallels, his rocketry crew at Caltech was known as the “Suicide Squad,” and he looked like Howard or Tony Stark. Reading about scientists like Parsons, Von Braun, Tesla, and Oppenheimer, as well as some of the adventurers and mystics of the first half of the twentieth century, makes me think that early comic creators might not have been as imaginative as I thought. Maybe the times were just genuinely weird and amazing.

I disagree with your dad’s thesis, though. I don’t think we needed narratives about heroes like Michael and Gilgamesh to look for a strong man to save the day. I think art was imitating life. That sort of thing just happened on a regular basis in the Hobbesian state of nature. There’s a common threat from human or animal predators or just environmental factors. Then, one person has an idea, or exceptional ability, or he just gets really frustrated and takes effective action. Others tend to follow the one who seems to know what he’s doing. That’s how the collective effort your dad talks about often starts. If the initiative-taker accepts the mantle of leadership (not a given), he may be a just and wise leader or a tyrant, or anywhere on the spectrum in between. See any zombie movie for examples. But stories describe that search for a hero that is a part of the human condition; they don’t inspire it.

I do have one minor quibble with this piece. I think young Earth (or young universe) creationists are a minority amongst Christians and other Torah-reading monotheists. Personally, I don’t even think the most literal readings support it. For example, there could be more than ten billion years between verse 1 and verse 2 of the first chapter of Genesis, and that’s before you even touch the debate over whether or not “day” was a correct translation.

I know that has nothing to do with your point, but the automatic characterization of Genesis 1 as a narrative of events of 6,000 years ago always irks me.

I think it’s more compelling to interpret Galactus v. Surfer in a gnostic vein: Galactus is the mad and wrathful demiurge, Surfer the word-made-flesh and saviour (who, moreover, gets exiled to the material world for his efforts).

Would that mean the archangel Michael isn’t really the first superhero after all, what with the senses shattering origin of the logos being retconned back to Genesis 1 by the gospel of John (In the beginning was the word and… the word was made flesh)?

Sounds right to me, Sean — even though that changes the title of the Gospels to Crisis on the Only Earth We’ve Got.

Only Earth…? Dunno, John Hennings – I’m no expert on that stuff, but seems to me that there are inconsistencies in the continuity of the gospels which suggests a universe with four parallel earths.

Or more, if you count gnostic and other heretical gospels. But I suppose they’re non-canonical, so…

Backing up to one of John’s earlier comments: I’m not entirely convinced that strong-men-who-save-the-day are just something that happens in the regular course of nature. Or rather, I’m not convinced that NARRATIVES about strong-men-who-save-the-day are “natural.”

This seems to be a kind of story we culturally like to tell. We could take the same events and construct a story that doesn’t emphasize the strong man; his heroism could be subsumed into the group and his intiating action could be framed as merely the first manifestation of the collective action. This would be no more or less accurate a story to tell.

But we like heroes. And though the trend is ancient, I think it picked up steam after the American and French revolutions, as seen in the advent of Carlyle’s “great men” and Emerson’s “representative men” and Doestoyevksy’s “extraordinary men” and Neitzsche’s “Superman” and Siegel’s “Superman,” all of whom owe some DNA to Napoleon, the strong man who saved France from post-monarchy anarchy by establishing the idea of a new monarchy of strong men.

Utlimately I think the angel Michael is a different animal because he isn’t human and his power is an extension of God. Napoleon is one of the most influential heroes/anti-heroes in part because he disregarded the idea of divine power by overthrowing the God-chosen king. Instead of a divine being dropping down from the sky to save us, a human being imagined himself into a “superior being” (what Napoleon called himself) and rose upward.

Right…pre-modern heroes often get ground up by fate/the gods; the heroism is in accepting limits rather than in overcoming them. I think the advent of superheroes overcoming adversity is part and parcel of the move from (ancient) tragedy to (modern) melodrama. As such it’s arguably part of the move towards democracy…or at least towards populist systems of government (which would include modern totalitarianism as well as democracy.) The superhero relies on/embodies the idea that human beings should overcome injustice and impose their will on fate.

It seems paradoxical that democracy and totalitarianism could be part of a shared phenomenon, but I think that’s exactly right. Totalitarianism before the rise of democracy was called monarchy.

Chris, it seems to me, at least judging by stories like Heikei Monogatari, the epic of Gilgamesh, The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, and the earlier passages of The Mabinogion, I think we can safely say the desire to tell stories of great people doing heroic deeds is broad, if not general, and stretches beyond western and Christian cultures in a way that suggests, though it is not the only narrative form, it is a standard and ‘natural’ one to engage in. That we tend to like it is no objection to this.

Noah, I think there are a number of premodern heroic stories which feature heroes not ground down by divinity. In many cases, this is because they are extremely pious, but it is not always so. The characters of Beowulf, Robinhood, Cao Cao and the ultimately victorious Sima clan (from Romance of the Three Kingdoms), and Gilgamesh spring to mind. Robin is the only one of these who could be understood as counter-regal, since he was originally a yeoman, while the others are all kings. None of their stories are particularly democratic. But perhaps these are just the exceptions.

Chris — right, but monarchy is based on conservative rationale — i.e., we’ve always done things this way, or divine right. Totalitarian regimes are generally built on idea of popular/national will; ideology isn’t all that different from that of democratic governments. It’s all mass politics.

To Tavis’s examples I would add the historical Nimrod (the original, not the Sentinel), Imhotep, David son of Jesse, Gideon, Cyrus, Maccabeus, Leonidus, Alexander, Spartacus, Julius Caesar, Genghis Khan, Ahmad Shah Durrani, etc. The “Great Man” theory of history was commonly held a long time before it was formally articulated.

Sean, have you ever done interviews for historical research, or the eyewitness accounts of an complex event? I think the inconsistencies are very consistent with those — so much so, it actually adds to the credibility. If they were right in line on everything, that would be clear evidence of editing for content. Mark is believed to be the first Gospel written. Even among the most conservative scholars and some early church writers, opinions vary widely on which Mark is meant by the name (added after the authorship) and whether or not he was an eyewitness. Matthew and John, of course, are traditionally attributed to eyewitnesses, although even they were not present for every event they described. Finally, Luke was a Greek writer who was very much in line with what became Western historical tradition — research, multiple eyewitness interviews, careful fact-checking, etc. — at least by his own description.

John, Fair enough, point taken about eyewitness accounts… taking my tongue out of cheek for a moment though, the synoptics are much harder to reconcile with John surely. But that’s all getting a bit off topic….

Chris Gavaler – “divine being dropping from the sky” Isn’t that Superman? He might share DNA with Napoleon, but more with any number of imaginary divine beings (the word made flesh for one, seeing as I was going on about that earlier). And Jack Kirby’s stories were full of stuff bought over from the old country.

Don’t disagree with most of what you said about how narratives changed with the rise of capitalism (“democratic” or otherwise), but… maybe those changes aren’t always qualitative differences.

-sean

Sean, I’d say Superman is different from an angel because of his simultaneous identity as Clark Kent. If Superman descended, took out some villains, then returned to Krypton where he resides until called upon again, then that would probably fit the St. Michael model. But Superman-Clark is much more of god-human hybrid. I think that’s a key element in superheroes. And, yes, the word made flesh follows that superhero pattern too: Jesus Christ is a demi-god, part-human and part-God. The original Kirby Thor was a human who gained the powers of a god, so not an angel descending but more a human ascending to superhuman status.

Sean, I think I agree and disagree. In some ways, the Gospel of John is easier to reconcile with the synoptic gospels than the synoptic gospels with each other, simply because John is telling a separate set of events. The events and utterances in John don’t really contradict anything in the synoptic gospels (speaking generally, without doing a line by line comparison). It’s just more of the inside story of Jesus’s ministry, a little like a biography of Patton’s war years by his driver. And it’s easy to explain why John didn’t cover many events; others had already done so well enough.

What’s difficult for me to explain or reconcile are the very significant events covered in John and nowhere else. I mean water into wine at a wedding reception — not a big deal. Only his mother and some of the host’s party staff even knew about it at the time. It’s even easy to imagine Mary telling John all about it, given that Jesus had established a kind of adoptive family relationship between the two at the Crucifixion. But Lazarus’s public resurrection? The catalyst for the events of the Passion Week? Why would you skip that? Mark: “Oh, man, I forgot to mention that Jesus totally resurrected Martha’s brother, and the people went nuts about it and the Pharisees decided enough was enough. Oh well, I’m sure the next guy will cover it. I mean, it definitely won’t take three more biographies to finally relate that key event.”

Chris, that makes sense, but… the character I recall from reading the comics was quite a bit more powerful than the original Siegel/Schuster version. So I wonder if Superman is becoming progressively more “divine” over time – isn’t Wonder Woman his girlfriend or something these days? – and whether something similar might not have taken place in earlier times; with popular culture in the ancient and feudal worlds being purely oral, it can be hard to know how some mythic characters first took shape before being written down. Which by definition, meant for consumption of the upper classes, so heroes (for want of a better word) had to become at least aristocratic.

John, Lazarus? Thats the problem I have with religious narratives – they keep bringing the characters back from the dead.

I wasn’t really thinking of specifics, more the general take on Jesus which I took to be more gnostic in John… But to be honest, being an atheist I don’t feel a need to reconcile that stuff – no religious no-prizes for me any time soon – but I imagine some sort of retcon may be called for. Strangely enough, retroactive continuity turns out to be a term first coined by – face front true believers! – theologians….

http://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Retroactive_continuity

Sean, it’s too bad Noah doesn’t give no-prizes for irony. You’d have one for sure. And that’s fascinating about retroactive continuity. It draws a nice parallel between our understanding of God’s authority over (and existence outside) the universe and the similar position of a comic book creator. We theists are all Grant Morrison’s Animal Man. I’m not sure I agree with the original coinage of the term though. Without diving too deep, it seems like it implies a God who is less than omniscient, and must therefore rewind and correct.

I recommend all the Gospels, but especially my namesake. If I’m wrong about Jesus and they’re just novellas written to support an elaborate conspiracy, they’re still good ones — full of cosmic drama and realistic human pathos.

John, A Noah-prize! If the HU gave them out, who wouldn’t want one?

Don’t know why the continuity thing implies a less omniscient deity. I’d have thought the opposite, with omniscience by definition extending across all of reality (“rewind and correct” being simply the perception of beings with limited movement in the fourth dimension).

Btw, nice to chat with someone who can combine a sense of humour with their religious conviction (although I’m sure saying that indicates a prejudice which is a failing on my part).

Instead of an empty envelope for the Noah-prize, I’m imagining a Wonder Woman statuette cast in the style of Harry Peter’s art — the proud centerpiece of any erudite fanboy’s mantle.

Good point regarding the term and our perception of it. That’s much more in line with my image of a God who is planning far ahead for events that have yet to occur — because he can see past, present, and future simultaneously, from a position outside of time. If I said that at all well, it was with words I stole from C.S. Lewis.

Thanks for the compliment, Sean, and the feeling is mutual. I think Jesus wants me (or would want me, from your perspective) to deal with other people in a civil, gracious manner. I also don’t think I’m supposed to take myself too seriously. (Of course, based on the example of the Gospels, if you were a legalistic, hypocritical religious leader exploiting his own flock, a different demeanor is required.) I know there are plenty on both sides of this debate that behave in a hostile, condescending or otherwise insulting manner, but I wish it were not so. In that sense, HU is kind of a safe haven for me — a place to talk about faith and skepticism (and other very charged issues, like race) with courteous interlocutors. And I always learn something cool, like the fact that “retroactive continuity” came from theology. Now if only Noah would open a pub or coffeehouse in my neighborhood…

“Is required” should be “would be required.” I take grammar and the subjunctive mood *very* seriously.