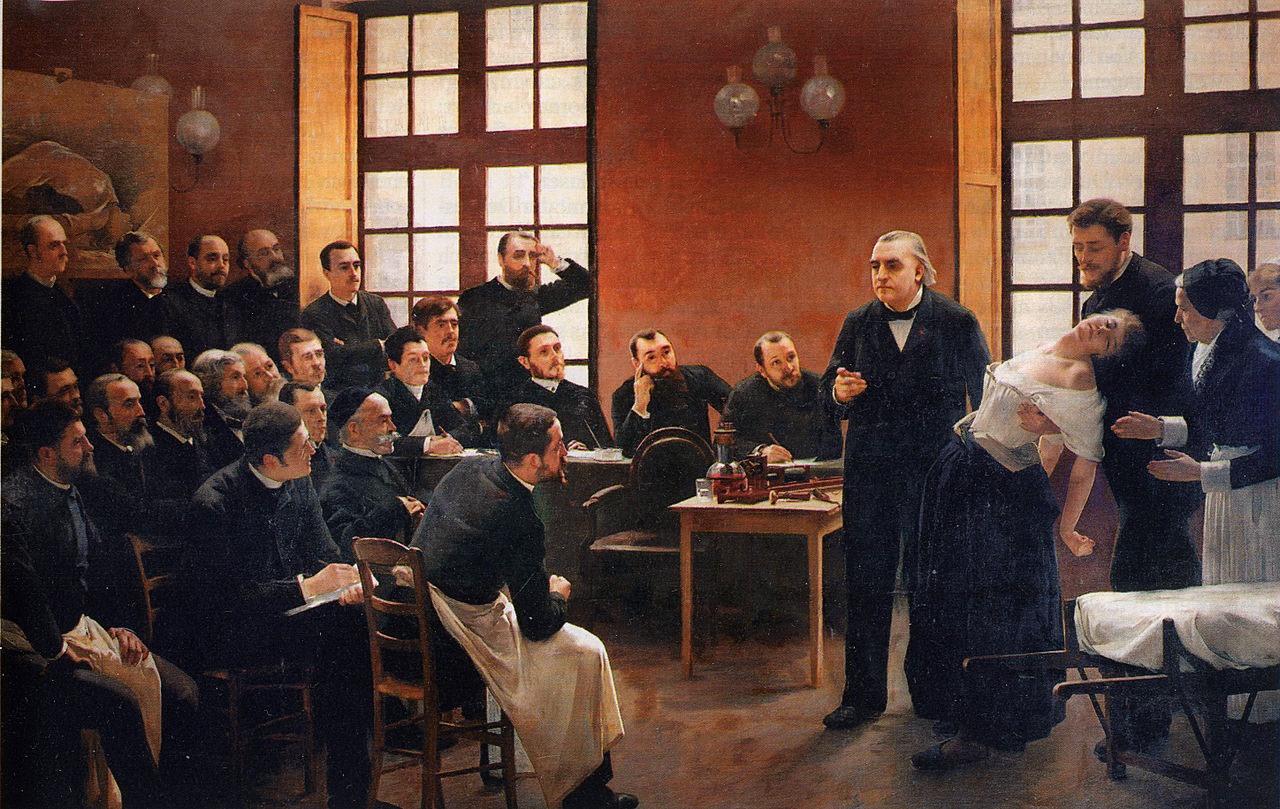

Over the last few weeks, Brooklyn’s Morbid Anatomy Museum has held a series of lectures on the historical context of hysteria and the often bizarre treatment of hysterical patients. In her first talk, Asti Hustvedt, author of Medical Muses: Hysteria in Nineteenth-Century Paris, described in fascinating detail the transformation that hysteria underwent as a result of the work of revolutionary neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot.

Charcot’s innovation was in re-characterizing hysteria from an intrinsically feminine form of madness to a neurological disorder like any other, capable of affecting both men and women alike. His research at the famed Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in the late 1800’s was dedicated to studying and popularizing this new approach. Though they didn’t last long, his ideas about hysteria changed the way we thought about the human mind and gender, laying significant basis for the Freudian revolution just a few decades later.

Obviously sensing he was onto something, Charcot became known for putting on public events in which his hysterical patients would literally “perform” their symptoms for spectators. Charcot would personally select patients with the “best” symptoms to present, inducing the outrageous and shocking behavior through hypnotism and other quasi-occult practices. In this way, suffering from severe hysteria became a twisted form of celebrity.

The other night, with Hustvedt’s discussion fresh in my head, a provocative thought occurred to me. Charcot died in 1893, but his popularization of hysterical femininity as celebrity is still with us today. Inducing and performing hysterical symptoms form the basis of much of what we call “reality TV.” Nowhere is this more apparent than on ABC’s The Bachelor.

Put another way: Chris Harrison is the cultural reincarnation of Jean-Martin Charcot, and the Bachelor Mansion bears a striking similarity to the Salpêtrière, transported from nineteenth-century France to modern-day Los Angeles.

Let me explain.

Throughout this discussion, “hysterical” should not be construed in its common, disrespectful sense as simply an “out of control” woman. I’m sensitive to the fact that the concept of hysteria has been historically misinterpreted, abused, and put to obviously chauvinist ends.

s used here, “hysterical” is no insult. I am not attacking or judging the women on The Bachelor, and I also do not want to oversimplify them as people. My analysis represents simply one view of one aspect of their individual personalities.

I am using the term “hysteria” in its strictly psychoanalytic sense. Hysteria has been described in various ways by differing schools of psychoanalysis, but each of them seem to associate it with gender identity and the need for love.

Freud founded psychoanalysis based on his study and treatment of hysterical women, initially linking it to repulsion over childhood sexual experiences or fantasies. But over the years, Freud’s conception has been significantly refined.

For example, Hendrika Freud (no relation) describes the hysteric’s situation as this: I want to be loved, and how can I be loved? Slavoj Žižek formulates the hysterical question as a crisis of sexual-symbolic identity: What is it about me that causes you to say I am a woman? Darian Leader remarks that while men resent women’s bodies for not “speaking” to them, “hysterics are in general women whose bodies do in fact speak.” Christopher Bollas says that the hysteric lacks “an unconscious sense of maternal desire for the child’s sexual body –especially the genitals.” Melanie Klein links the feminine propensity for hysteria with jealous aggression and guilt that young girls often feel toward the maternal body.

But more specifically for our purposes, consider the view of French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan and his disciples. According to translator and practicing Lacanian psychoanalyst Bruce Fink, “the hysteric seeks to divine the Other’s desire and to become the particular object that, when missing, makes the Other desire…the [hysterical] subject constitutes herself, not in relation to the erotic object she herself has ‘lost’, but as the object the Other is missing.”

In other words, in the clinical Lacanian sense a hysteric is someone who cancels out a portion of her subjectivity in an attempt to become the object-cause of desire for some Other –in our case, the Bachelor.

Fink uses feminine designations purposefully. The history of psychoanalysis confirms that the historical association between hysteria and femininity is no mere anachronism or prejudice, but says something deeper about the relationship between culture and mind. Freud struggled for his entire life to divorce the two, but as noted by Juliet Mitchell in Feminism and Psychoanalysis, in the end he found himself back where he started: either something about hysteria was inherently feminine, or something about femininity was inherently hysterical.

In her book Mad Men and Medusas: Reclaiming Hysteria, Mitchell says, “every context which describes hysteria links it to gender –but not, of course, always in the same way. Historically, the various ways in which gender differences and hysteria are seen to interact should tell us something both about gender…and about hysteria.”

Thus, the paradox that so agonized Freud is at least partially resolved if we focus on Lacan’s hysterical structure. According to this view, the historical and structural link between hysteria and femininity is simply a result of the extent to which women have been asked to become objects of male libidinal desire across cultures and throughout time.

With this view in mind, let’s go back to our conception of The Bachelor as a modern version of Charcot and the hysterical performances of the Salpêtrière. It is not enough to merely remark that it is fun or interesting to see women acting hysterical on TV. The question, of course, is why are they acting that way?

The Bachelor’s formula is as simple as it is effective: anoint a Bachelor, round up a number of single women and put them in a situation in which they’re asked to “win” the Bachelor’s heart. Ask them to dedicate themselves fully to attracting an idealized Other, to transform their identities into the object-cause of desire for that Other –in other words, adopt precisely the Lacanian structure of hysteria.

If we follow Lacan, adopting the object-cause means canceling out at least some, and perhaps too much, subjectivity in the process. Bollas offers a similar view from the point of view of object relations theory, arguing that “the hysteric’s ailment, then, is to suspend the self’s idiom in order to fulfill the primary object’s desire…the hysteric’s primary object will be the object-in-waiting that the hysteric must find in order to be recast as the other’s object of desire.” As the show aptly demonstrates, adopting this psychic posture can have disastrous consequences for one’s emotional health.

Thus, it’s no surprise that the institution of The Bachelor cultivates a smorgasbord of hysterical behavior in its contestant-victims: extreme jealousy, decentered identity, over-attachment to a functional stranger, histrionic behavior, and a lot, a whole lot of crying.

On this most recent season, no contestant modeled this account more consistently than Ashley I. Variously referred to as “the Kardashian” or “the virgin,” Ashley has displayed far and away the most frantic, bizarre, and irrational behavior of the season. She identifies closely with Disney princesses; she puts on ostentatious evening attire to sulk by herself and eat corn on the cob; she looks daggers at the other girls and adopts an annihilative stance; she runs away from the Bachelor in shame only to immediately reverse direction in desperation; each moment a prelude to tears. At her most passionately hysterical she becomes emotionally disintegrated, radically oscillating between sobs and bursts of dark laughter.

As indicated by her nickname, Ashley has never had sex and never had a long-term relationship. This fact, not altogether completely uncommon or extraordinary, seems to dominate the entirety of her personality.

But what is the value of Ashley’s virginity, and who values it? When Mackenzie hears about it early on, she expresses jealousy at the perceived advantage it gives Ashley. Virginity is frequently treated not as an aspect of Ashley’s personality so much as an object of libidinal exchange. We rarely hear what virginity means to Ashley. Instead, we hear Ashley worrying and speculating about what her virginity means to the Bachelor. (Compare Becca, also a virgin and the complete opposite of Ashley on this point.)

What I’m proposing here is that a major part of Ashley’s self is alienated in the Bachelor’s desire. Her sense of desire is one step removed from her, because it only accrues to her once filtered through the Bachelor’s desire.

Lacking the subjectivity necessary to own her own desire and instead devoted entirely to inhabiting the object-cause of the Bachelor’s desire, Ashley’s whole personality seems to be on the verge of collapse. That kind of dramatic tension is what makes Ashley and other Bachelor alumnae so compelling to watch. Love her or hate her, Ashley is a striking example of what happens when you structure too much of your personality around being the thing you think the other wants. All of us can relate to that.

Surprisingly, it wasn’t Ashley but Kelsey who actually experienced a collapse on a recent episode. Faced with the imminent possibility of being sent home, Kelsey forcefully confronted the Bachelor with an intimate story of personal loss. This was supposed to be her ace in the hole, a last-ditch gambit designed to ensure her desirability for at least a few more weeks.

But it didn’t work. Something told her that the Bachelor still wanted to send her home.

Ostensibly freaking out that he’s about to send a widow packing, the Bachelor panicked and canceled the night’s cocktail party in favor of standing outside on the balcony and staring into the bleak, abyssal night sky. Kelsey, suddenly overcome by anxiety, began rambling profusely to the other girls. Suddenly, she disappeared to a secluded corner of the mansion and was soon found lying on the floor, whimpering and writhing in anguish, in need of medical attention.

Some of the other women accused Kelsey of “faking” the attack, but that interpretation makes so little sense strategically that I am forced to assume the opposite. Whatever label you’d like to use, it appeared to me that Kelsey was experiencing extreme psychic pain at the moment.

Kelsey’s breakdown was about the hysteric’s relationship to rejection. Fink notes, “the hysteric constitutes herself as the object that makes the Other desire, since as long as the Other desires, her position as object is assured: a space is guaranteed for her within the Other.”

But what if the Other stops desiring? What if the Bachelor still wants to send you home? Psychically, the result is catastrophic: you disappear. As Žižek once put it, because “she is nothing but ‘the symptom of man,’ her power of fascination masks the void of her nonexistence, so that when she is finally rejected, her whole ontological consistency is dissolved.”

In other words, consider our understanding that becoming an object-cause of desire for the man involves a certain annulment of feminine subjectivity. Thus, when rejection approached and Kelsey’s feminine “mask” was pulled back to reveal the canceled subjectivity beneath, she suffered absolute existential devastation.

The “symptoms” (if the reader will permit me that word) suffered by Ashley and Kelsey may seem tame compared to the convulsions, somnambulism, and practically supernatural abilities of Charcot’s classical hysterics. But consider that some psychoanalysts and commentators have proposed that hysteria still exists today in concealed or muted form.

As Elaine Showalter discusses in her book Hystories: Hysterical Epidemics and Modern Media, things like chronic fatigue and multiple personality disorder may have roots similar to those of hysteria. Only fifteen years ago, Bollas called for a reassessment of hysteria in the psychotherapeutic community based on his view that hysterical patients are frequently misdiagnosed as borderline personalities.

But more broadly, hysterical behavior may be found anywhere a person –a woman, usually –is somehow motivated or forced to become the object-cause of desire for someone else.

Today, it’s easy and typical to think of hysteria as either a historical curiosity of the pre-Freudian and early Freudian world, or a chauvinist label applied to women considered “difficult” by patriarchal society. But as psychoanalysis and The Bachelor tell us, hysterical femininity is still with us –and it will be until normative concepts of femininity radically change, until feminine identity is allowed and encouraged to take up the position of sexual subject.

For more like this check out syvology.com and follow Tom on Twitter – @syvology

That video is incredibly painful to watch. I kind of can’t believe they showed it, and added “intense” music to boot.

I love horror films, but I find the sadism of reality television viscerally disturbing.

It was something else. Kelsey turned out to be basically fine (physically, at least) shortly thereafter and survived for another week. But the producers didn’t let that last long, because they immediately elected to put her on a mercilessly tense two-on-one date with none other than Ashley I (the other woman discussed above).

They of course both melted down and were left alone in the middle of the desert as the Bachelor escaped on a helicopter (seriously).

From what I can gather by following them both on social media, Ashley seems OK but Kelsey may never be the same.

Holy crap. I hope they’re paying her medical bills at least.

How do the people who put these shows together live with themselves? I knew the cast was humiliated, but I guess I hadn’t realized that they were actually traumatized.

Is it possible it’s (The Bachelor) all for ratings and media buzz? Your comprehensive analysis notwithstanding, it’s a TV Show conceived and constructed to sell ad time – even your video insert (youtube) has an ad.

Not sure what your point is Stacy. Shakespeare plays were meant to make money too. So what?

Right, even if we assume that everything that happens on the Bachelor is 100% scripted for maximum for-profit drama, I don’t think that’d change anything. The analysis would apply equally to fiction, non-fiction, or quasi-fiction (like reality TV).

So, I’m wondering, is there such a thing/identifiable experience as a feminine subjectivity? If femininity is defined as being “object cause,” or even if that’s one significant aspect of femininity, isn’t her very subjecthood under perpetual erasure?

I really loved this article! Sorry I showed up so late.

To be more specific, Tim, you say: “hysterical behavior may be found anywhere a person –a woman, usually –is somehow motivated or forced to become the object-cause of desire for someone else.”

I have always seen object-cause at work in the “she was asking for it” argument, or “what did she expect wearing that skirt.” With these arguments, the feminine body is understood to be a de facto invitation to sex, whether the woman understands it to be or not. Here, a woman’s (aWoman’s) body literally negates/trumps her own intent, pending she even had one other than existing peaceably. She is object for other. She is not a subject because she is incapable of establishing her own intent or will separate from the community’s/man’s interpretation of her body.

If a woman is NOT interested in being a sexual object, the burden is on her to evaluate her body (the condition of her existence) from the perspective of a man who blames other people’s body parts for his own desire/actions/inability to control himself.

As such, a woman’s body is always already inscribed with the sexual desire of the other. And that condition is innately hysterical because her words don’t mean but her body does… even when she speaks rationally. She is not afforded the voice to speak for her body. Her body is a fantasy for others. And it is her responsibility to anticipate these fantasies (Hysteria).

Your reading, which is very interesting, seems to posit the object-cause as a traditional feminine role or even look/presentation/way of constituting a self/identity that one might choose (to one’s own detriment). I have a tendency to see it as proof that men are cultured to be overgrown, entitled babies blaming others for their own thoughts and actions, and that there is no “outside of that” for women. Therefore, for me, to be a woman is to be a hysterical object-cause, not by choice or nature, but by interpretation within a patriarchal culture to which there is no outside/escape… short of becoming a wild mountain woman… but even then.

I’m wondering how these interpretations jive. I agree that the contestants on The Bachelor have set themselves the task of being object-causes for the Bachelor. But I also think they already are, more broadly. I’m wondering what possibilities of agency, if any, might be attributable to the position of object-cause and the extent to which a human being can control it, i.e. how one is perceived.

Hope that makes some sense. Thanks.

Wow, that’s a great discussion, Nix.

I just read a book by William Davies about happiness he talks a lot about the way that economists/pyschologists try to interpret happiness through biology or money exchange rather than through talking to people; expert interpretation rather than giving people agency to define themselves. There’s a sense in which you could see modernity as promoting, or predicated on inscribing, hysteria (esp on women, but on others too.) Sort of fits with one of the great crucibles of hysteria; trench warfare during World War I.

That’s very interesting. Freud’s Aetiology of Hysteria (1896) initially concluded that Hysterics were incest survivors. In 1924, Freud went back and added a footnote (just one damned footnote) stating that these memories of trauma were not true memories but wish fantasies.

Just off the bat, that begs the question: What’s the difference between Hysteria and PTSD? One is a function of fantasy, the other of memory. But how does one ever know? (Even Freud knew he couldn’t really know.) There is an assumption of knowledge about another that allows one to speak for that other because they cannot do it for themselves, as if they are incapable of veracity, incapable of meaning. I *think* that’s the object-cause. This is interesting for me to think about. Thanks, Noah and Tom (not Tim).

Yes…Freud’s initial diagnoses of incest though often weren’t based on testimonies of those affected, but on his diagnosis (i.e., they were victims of incest, but they didn’t know, and he knew.) Or at least that’s my understanding (I read a lot about this for my book, but it was still pretty confusing as to what actually did or did not happen.)

Yes. You are absolutely correct.

Woah! Thanks so much Nix and Noah for the continued discussion. There are some really interesting issues here.

First, I just wanted to talk a little about Freud’s famous “shift” from seduction theory (i.e. that hysterical patients were victims of incest or molestation) to his theory of infantile sexuality. This, I think, was the most important develpoment of his career. It led to his entire theory of sexuality in the Three Essays, and eventually the oedipus complex and all that came that.

It’s easy to see how such a shift might be controversial, both in Freud’s time and today. But I think that the shift is often misinterpreted as totally rejecting the idea that childhood sexual encounters do happen and that they can be deeply traumatic. From what I understand, this wasn’t Freud’s claim at all. Rather, his shift to the oedipal theory was based on the idea that even if we assume that all childhood sexual encounters are traumatic and will lead to neurosis, that cannot explain every case of neurosis out there.

Neurosis, in his view, was simply far too common, and its characterisitcs from person to person far too varied, to have a single/objective etiological cause (in terms of a specific external event like child sexual abuse).

So I think the view among psychoanalysts today is that suffering some form of sexual abuse (or some other premature encounter with sexuality) as a child is a sufficient, but not necessary, condition for the emergence of neurosis (be it obsession or hysteria).

I think this is fundamental to the psychoanalytic account of subjectivity, because it implies that neurosis is not really a “disease” one catches and needs to be cured of. Rather, it’s a more fundamental condition of subjectivity itself. For instance, in Lacanian diagnosis, *every* subject is either neurotic, psychotic, or perverted in structure. There is no “normal” structure. Neurotic structure is essentially as close as one gets to being “normal”.

In other words, Freud’s shift was about dispensing with the idea that there is some normative, healthy human mental state that is given at birth and derailed only by trauma. Rather, psychoanalysis claims that subjectivity is problematic in itself (to varying degrees for each unique person, of course).

Also, I wanted to talk a little about Nix’s broader point having to do with the relationship between hysteria and feminine subjectivity itself. The issues you mention are extremely interesting and indeed they were ideas/angles I considered when writing this.

First, there’s the question of what the relationship between hysterical structure and feminine structure is. On the one hand, I think it says a little bit too much that they are precisely synonymous. Hysteria is intimately related with femininity but it’s not the whole story.

That said, the equation of hysteria and femininity is not only a historical/cultural stereotype but also has a lot of basis in some of the recent psychoanalytic literature. For instance, Darian Leader (a British psychoanalyst influenced by Lacan and others) has a book on sexual difference called “Why Do Women Write More Letters Than They Send?” He doesn’t actually describe it this way, but his discussion about what it means to be a woman (not just socially but psychically) closely tracks Fink’s discussion on Lacanian hysterical structure.

From what I can tell honestly, when Leader talks about constituting womanhood he’s talking about hysteria. This makes sense insofar as all “normal” subjects are neurotic and hysteria is the “feminine” half of neurosis, complemented by the “masculine” obsessional half. So, for Leader, to become a woman is to step into the role of the Other Woman that is perceived to be desirable to men (which is what we see happening in Hitchcock’s Vergito, for instance).

But Lacan had a lot more to say about sexual difference than just that. For him the two halves of neurosis were associated with one or the other sexed position but not directly linked. To understand Lacan’s real take on sexual difference requires delving into his impossible “formulas of sexuation”. I can’t really offer a comprehensive explanation of these, other than to say masculine structure involves a totalized set constituted by an exception, and feminine structure is a non-totalized set because there is no exception. The sexuation chart also keys into Lacan’s claim that “there is no sexual relation”, which which you refer to when you say that for a man, a woman’s body is always stuck in the realm of fantasy.

This kind of brings me to a second point.

There’s also the question of what it really means to take on the role object-cause of desire. In one sense, it may mean what it sounds like in common language, in that it denotes the status of actual object devoid of desire.

But the object-cause of desire in Lacanian terms is not really an object at all. It seems to the human subject to be an object, that our desire is for a particular object, but the reason for Lacan’s use of the phrase “object-cause” is that desire does not have an object, it only ever has a cause. The object-cause of desire is what’s known in Lacanian analysis as petit objet (a), and this is the non-symbolized residue left over from the process of apeaking and symbolization (i.e. of being a subject itself). So we say “object” but what we really mean is a psychic mechanism that produces desire.

So, what’s important about this is that if femininity is related to a cause and not an object of desire, that means that it’s really not about prioritizing the desiring Other at all. Fink describes it as the Other really being just a “puppet” for the hysteric, insofar as the hysteric’s plan is not to actually satisfy the Other but to keep it desiring, to constantly elude it.

Another important wrinkle on this is that it is not the case that the hysteric, even as constituted as a cause of desire, is not a desiring subject. She is a desiring subject, the only difference is that her desire is first routed through the manipulation of the other’s desire. This involves an identification with the Other; she investigates the nature of the Other’s desire so that she may desire herself through it. So, while hysterical/feminine subjectivity does require a certain triangulation or indirect route to experiencing desire, it goes too far to say that she is not desiring at all.

One should also note that hysteria is by no means the “passivity” often associated with objecthood and/or feminity. In fact, many psychoanlytically oriented feminists view hysteria as a form of violent protest against the patriarchal imposition of submissiveness.

I’m not sure any of that made total sense. I’m totally self-taught in Lacan and psychoanalysis generally so I’m sure I’ve missed a lot and done a less-than-perfect job at explaining it all in this case. But seriously thank you so much for reading and for contributing some comments/criticism here. I had to make a lot of decisions when writing this piece in terms of how to lay things out and what to focus on in this context. So although I didn’t want to get hung up on some of the trickiest nuances of this stuff for the piece itself, I’m glad you brought it up!

Lastly, I just want to mention that Jessica Benjamin’s work on sexual difference and sadomasochism might be helpful in this context. She’s (mercifully) of the relational school of psychoanalysis, so she doesn’t rely on any Lacan.

I won’t prattle on any longer here but if you want check out a thing I wrote about one of Benjamin’s books and 50 Shades of Grey here:

http://syvology.com/2015/03/10/50-shades-of-grey-duke-of-burgundy-and-the-intersubjective-dimension-of-sm/

Thanks again, I’d love to hear your thoughts on any of this!

Thanks for your comments, Tom, in particular the last. You’ve given me a lot to think about. I’m still mulling it over.