It’s been a whirlwind week or two here at the Hooded Utilitarian for discussing race in comics. Building on earlier treatises about Black Panther’s exercises in assimilation narratives, Black Lightning’s equivocation on race and the X-Men turning black Noah Berlatsky asserted that the original Milestone Static comics kind of suck. J. Lamb argued that the superhero genre is fundamentally white supremacist, which makes most all black superhero characters generally useless.

As a black comics fan, this is abjectly depressing.

Everyone knows that black comic heroes hardly register as competition against white heroes for popularity. They barely exist. The fact that having one non-white costumed character on the big-screen is typically seen as an enormous boon for diversity is pretty demoralizing. When you add this to the fact that, as J Lamb wrote, non-white heroes function “within a paradigm defined by Western perspectives on violence and ideal beauty, in an industry dependent on White male consumer support .” I’m left feeling outright bamboozled.

The truth wouldn’t sting so much if these essays were written some time last year, but they just reaffirm what I had concluded after reading All-New Captain America #1. One of the most banal, vapid comics I’ve ever read, All-New Captain America#1 truly underlined the utter fecklessness of the black super hero. We have Sam Wilson, the first African American super hero in the role of Captain America with all of the variant covers and implied importance that the role suggests, adorned in the American flag boasting a triumphant reach to the utopic mountaintop, published within twelve days of the announcement that Darren Wilson would not be indicted for shooting Michael Brown. The book’s lack of self-examination makes the juxtaposition painfully jarring.

It isn’t as though I had ambitious hopes for the new Black Cap book. But I honestly thought the idea of a black Captain America would mandate a minimal degree of content, especially with books like TRUTH in Marvel Comics’ rearview. In this series, we’re presented with pages of wintry, hoary dialogue where Sam Wilson briefly recalls the death of his parents whilst dodging gunfire for no reason. He battles Hydra and fights Batroc, the French stereotype in a typical superheroic battle that is requisite for a Captain America comic, I suppose. However the concept of a black Captain America and what that means to him or anyone is completely passed over for an adventure typical for white Steve Rogers. The issue eschews moments of reflection from Sam, opting instead to toss in empty critiques of America’s obesity problem and government corruption. Remarks by the villains on how Sam’s nothing more than a sidekick are carefully worded; the reader can infer racial bias if he or she feels like it, or ignore it if the idea of a villain being racist is too upsetting or unpleasant.

Exploring the importance of Sam’s new role should be a no-brainer. Why else was an irrelevant Joe Quesada ushered back onto the Colbert Report to promote the book? Comic readers understand diversity is often an empty gesture in comics, but this is “Captain America”. I had no real fantasies about Sam talking about systematic racism or making birther jokes, but that the book literally says nothing about how the figure representing America as its premiere superhero is now black reveals how ruefully optimistic I was when expecting comments on the black super hero’s existence from a white writer.

The disappointment isn’t just mine. Writer and Public Speaker Joseph Illidge wrote about the first issue of All-New Cap on his weekly column for Comic Book Resources, “The Mission”. When reading it, you get the sense that he’s holding back a deeper sense of disappointment than he’s letting on. Lines like “I’m not going to make this a polemic on non-Black writers writing Black characters, because the dialogue on that subject may very well be reaching its golden years. That said, I would have preferred a Black writer handling this book.” Reading that, I can’t help but see an image of eyes clenched shut and a setback induced sigh.

He mentions the HBO series “The Wire” and says how it was a show where white writers presented black characters with a strong sense of authenticity. Illidge labels “The Wire” as an exception, and reiterates that white writers will almost always miss out on the nuances of the black experience. In the 50+ to 75+ years of Marvel Comics’ history the company has been generally viewed as the more diverse universe when compared to DC. Surely at some point, in all that time, one of those characters managed a convincing portrayal of the black experience.

As J Lamb wrote, black heroes can only do so much within the confines of the white establishment they exist in. Luke Cage may get his origin story from wrongful imprisonment and Tuskegee-inspired experimentations, but he won’t spend his super hero career warring on the treatment of black people by white authority. But it’s with relief that I recall a series of issues during Stan Lee and John Romita’s run of The Amazing Spider-Man where the sole black supporting characters Joe Robertson and his son Randy interact with each other in ways which feel honest and timeless.

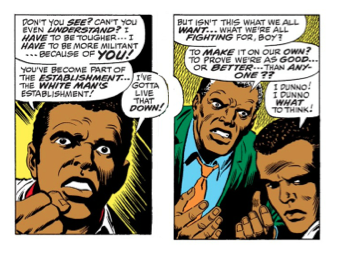

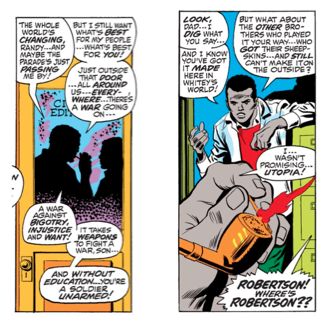

In Amazing Spider-Man issues #68-#70, Randy gets involved with campus protesters who want the school Exhibition Hall to be used as a low-rent dorm for students. It leads into a number of scenes where Joe and Randy try to convince each other what’s right for a black man to do in the modern world of 1969. Quotes from Robbie like “A protest is one thing! But, the damage you caused..!” resonate sharply with the critics of the Ferguson protestors. The same goes for Randy’s comments about militarism, which mirror protestor Barry Perkins comments about feeling triumphant while fighting back against the police during the Ferguson protests.

A few issues on, in #73, the creators include a scene in which Joe and Randy discuss college. Randy protests his social placement, exclaiming “What’s the point bein’ a success in Whitey’s World? Why must we play by his rules?” Joe (or Robbie as he’s often called) maintains that by only educating one’s self can one truly bring about societal change. Randy, looking out at the reader, asks his father to explain why, if that’s true, educated black men in America haven’t prospered. Robbie has no response — he’s interrupted by J. Jonah Jameson bursting into the room ranting about Spider-Man. As in Static #4, where Holocaust’s grievances with racial inequality evaporate the minute he tries to kill a white child in cold blood, the discussion on racial inequity is silenced when the white guy (and, thematically, the white hero) enter the room.

But whatever it’s limitations, the fact remains that the two black characters in this comic are having a realistic discussion about racial injustice and how to deal with it. Randy isn’t presented as a hothead who doesn’t know any better (there was another character named Josh for that during the Campus protest arc), and Joe isn’t shown as a stodgy relic of the old guard. Education is said to be key to enlightenment, but Randy questions the very system providing the education. The scene is interrupted by a white man, but it has no easy answers for a white audience.

But the Robertsons aren’t super heroes.

So what’s the point? If black super heroes can’t engage in this type of discussion in any meaningful way, what does it matter that black supporting characters do?

If the super hero genre has been inherently, historically white, it’s all the more important to note those moments when white creators and black creators attempt to relay the black experience. It’s also important to note where they go wrong and to examine how, despite their efforts, superheroes continue to present a narrative of whiteness. The few successes can perhaps serve as a template for the future, so we don’t have another All-New Captain America to suffer through. Those few scene with Joe and Randy suggest that meaningful diversity is possible in a superhero comic, however unattainable the whole of the genre appears to make it.

I figured the Cap wouldn’t be any good, but this sounds worse than I feared….

Man, my super villain name should be Killjoy.

Excellent piece! I especially enjoyed learning about Amazing Spider-Man’s take on the middle class Black family’s generational disagreement on political militancy; Lee Daniels’ The Butler centered much of that film on the same dialogue.

Noah and I participated in a Twitter discussion yesterday where fans of increased race diversity among superheroes lamented my idea that the superhero concept is inherently White, and therefore inappropriate for substantive, authentic non-White characterizations. The conversation reminded me that many superhero comic fans could care less about substantive, authentic Blackness when reading or watching superhero media — they just want someone who looks like them in the role of the Hero. They want to appropriate the fantasy, without questioning it’s logic.

Articles like this remind us what happens when their wishes are granted by an industry more concerned with Black entertainment spending than Black history, politics, or culture. Well done.

I would love to read that book. The one you are referring to. The book where Sam Wilson, a black Captain America struggle against racial injustice, prejudice and xenophobia while also trying to create a better America for its citizen. A book with point of views, that encourages discussion and present themes and move the discussion forward.

I am not surprised that any important themes have been pushed aside in favor of the typical comics power fantasy Hero VS villain crap. Rick Remender had a chance with Uncanny Avengers to tackle similar issues of race and prejudice and it all but withered after 5 issues. The team fight the Red Skull, and after that, some form of time travelling Kang the Conqueror via Apocalypse-related villain. It was nothing more than the next steps of what he had already written before in X-force. He just doesn’t appear to be very interested in these types of issues so it was quite surprising to see he was going to be handling this book. It doesn’t feel like the most able group to tackle this. I would much prefer to read a comic that was interested in actual themes rather nothing at all. I have avoided the book so far because of this. It just reinforces the idea that these characters and stories, the concept of the superhero, is an homogeneous mess, where race and sex are interchangeable with an underlying heteronormative norm attached to everything. Never challenging the status quo. Never confronting the reality that if you want to write a different story, you must tackle different themes.

The underlying assumptions seems to be that it’s only a matter of time before we revert to the same old white Captain America of the past 7 decades. Why not use this opportunity to create something of value. The concept is relevant and interesting, but the execution is a mess.

J. Lamb: “They want to appropriate the fantasy, without questioning it’s logic. ”

Alternately, they want to claim a fantasy that belongs to them as much as to white people, just as black hero-myths belonged to pre-European African tribes as much they did to Europeans.

But if you think, along with Barthes, that the only type of stories you think “people of color” can tell are about their being stigmatized as “people of color,” then I guess you’re welcome to that belief.

> The conversation reminded me that many superhero comic fans could care less about substantive, authentic Blackness when reading or watching superhero media — they just want someone who looks like them in the role of the Hero.

We also cannot forget that the way fans of color engage with characters and stories can re-circuit and re-interpret those stories in way that provide the kind of productive identification that challenges that tired old repetitive and thoughtless representation.

Oops! I wasn’t quite finished. . . I meant to add that this kind of work – what I call “(re)collection” in my dissertation project – is not very useful, however, for breaking that cycle of representation as it reinforces the simultaneous one-dimensional and paradoxical presumptions of the dominant culture.

Gene, I can’t speak for Barthes. I suggest that the desire for full inclusion of people of color in the superhero concept is an exercise in futility. I suggest that Black hero-myths do not inform the superhero concept at all, and that people of color are more than welcome to develop modern narratives from those hero-myths.

I’m confident though, that the characters developed from that process would not be recognizable as superheroes.

My position that the superhero concept itself frustrates progressive efforts to racially diversify mainstream superhero comics does not suggest a paucity of vision on the part of non-White comic creators. Nowhere do I suggest that the only stories people of color can tell involve being stigmatized as people of color. But it’s clear that over eight decades of mainstream superhero comics leave readers with many examples like Sam Wilson’s Captain America: superheroes with dark skin who avoid any narrative connection to any discernible diasporic Black experience, artificial Black men wearing primary colored spandex tighter than most brothers would allow in public. Gene, if diversity should inform modern superhero comics, how do you explain recurring comic industry failures like All New Captain America #1?

People of color have purchased superhero comics for generations, yet the comic industry still prints diversity gimmick superhero comics and sends Joe Quesada or someone to The View to revel in mainstream applause for tolerating members of the darker nation behind the cowl and under the mask in panel. I find this dynamic offensive, and it’s the progressive desire for more culturally detached (insert identity here) superheroes that keeps race and gender gimmickry alive in comics.

We deserve more than a Black face and a power set. I’m not asking for reparations; just comics that don’t insult both my race and my intelligence.

“Alternately, they want to claim a fantasy that belongs to them as much as to white people, just as black hero-myths belonged to pre-European African tribes as much they did to Europeans.”

That seems like a fairly confused analogy. I mean, if I said, “KKK pulp of the early 20th century belongs to black people as much as to white people, because it’s all hero stories” — that would be transparently false, right? Superheroes aren’t as white supremacist as KKK pulp, I don’t think. But that doesn’t mean they’re not white supremacist at all.

I’m overall less cynical about the possibilities for black superheroes than James is…I think Ms. Marvel deals with issues of race thoughtfully; I think Truth ultimately fails but comes close enough to succeeding that it suggests that success is posible. I think Open Mike Eagle for one does great things with the superhero idea and blackness. But, given the longstanding record of failures, skepticism seems like a reasonable response.

Interestingly there have been significantly more successful female superheroes. Wonder Woman, Sailor Moon, Buffy, and I think even Twilight…there are quite a few of them. Race seems more of a barrier to superheroes than gender.

I guess one caveat there is that there are recognizable manga superheroes I think…Japanese superheroes in Japan aren’t exactly the same though. I don’t think Astro Boy can really address James’ or Donovan’s criticisms.

Gender is definitely less of a structural problem than whiteness. While Remender is muffing it over on new Cap, Jason Aaron has directly addressed the new Thor’s status as a woman. The bit with the Absorbing Man is clumsy, but the plot line where a returned Odin tries to throw his weight around and All-Mother Frigga does a end run on him to aid Thor is more promising.

Comics Should Be Good just did a month of comics by black creators, and I thought this one (Ajala: A Series of Adventures) stood out:

http://goodcomics.comicbookresources.com/2015/02/26/month-of-african-american-comics-ajala-a-series-of-adventures-books-1-3/

J. Lamb,

I asked, albeit indirectly:

“But if you think, along with Barthes, that the only type of stories you think “people of color” can tell are about their being stigmatized as “people of color,” then I guess you’re welcome to that belief.”

And you answered:

“superheroes with dark skin who avoid any narrative connection to any discernible diasporic Black experience”

I appreciate your directness in stating your priorities; I’ve sometimes found it very difficult to get such straight answers from sociologically minded comics critics.

The question is, however, to what extent those priorities reflect Black Experience. I presume that you were being humorous earlier when you called yourself a “killjoy,” but ask yourself this with some degree of seriousness: when Black People read anything for recreation, do they all want to reminded, 24-7, of the Struggle? Is there no room within Black Experience for enjoying carefree pleasures, of being Luke Cage having a sociologically irrelevant dust-up with Doctor Doom?

Or would the suggestion of that possibility constitute an attempt to appropriate Black Experience into the Monolith of the White Culture Industry?

To be continued (to keep this post short)

J. Lamb asked me:

“Gene, if diversity should inform modern superhero comics, how do you explain recurring comic industry failures like All New Captain America #1?”

Kudos on referring back to the topic of the original post, but I have not read the comic and can’t comment on it directly. I have certainly seen my share of dumb-assed comics about Phony Black Characters, a few of which have appeared in other Captain America comics. (A few came about more out of ignorance than malice, as with Mark Gruenwald transferring the name “Bucky” to an adult black male superhero.) I’ll also note that whatever a white reader sees as Phony Black Characters is probably a pale (no pun intended) imitation of what many black readers see– though I make the caveat that not all black readers see the same things.

You say that you just want “comics that don’t insult both my race and my intelligence.” OK, but is it an insult to either to imply that the escapist reading-material of black readers might not always be about The Struggle? When you say that any black hero-narratives derived from white superhero narratives would not be recognizable as superhero narratives, aren’t you implying that anything that isn’t about the Struggle is patently irrelevant to Black Experience?

Noah said:

“That seems like a fairly confused analogy. I mean, if I said, “KKK pulp of the early 20th century belongs to black people as much as to white people, because it’s all hero stories” — that would be transparently false, right? Superheroes aren’t as white supremacist as KKK pulp, I don’t think. But that doesn’t mean they’re not white supremacist at all.”

“White supremacist” means nothing as applied to superhero comics unless you extend it to all those comics that represented whites as the dominant class– and that means all of them, in all genres. You would also have to extend it to all entertainment that reflects the same proposition, which of course is very nearly everything in the twentieth century.

I realize, Noah, that the alleged connection between superhero pulp and KKK pulp is one of your beloved hobbyhorses. Plainly I won’t talk you out of this one anymore than you could talk me out of drawing parallels between archaic myths and 20th-century pop culture. So I guess we must settle on saying that I simply don’t recognize as significant the parallel you advocate.

On a positive note, I too appreciate that Donovan reprinted the Spider-Man scene. Whatever the limitations of the dialogue, I should note that Stan Lee may have felt comfortable in attempting this exchange because it was the sort of thing audiences were seeing in prestige “social problem” films of the time.

It’s not quite the same today. It’s a toss-up as to whether a lot of white writers won’t attempt this sort of thing because they’re actively seeking to “blanderize” the characters, or because they’re leery of making some public misstep that gets them bad press.

Gene, I think there are some connections between KKK pulp and Superhero comics, mainly because Chris Gavaler has done research on it, and he makes a convincing case. But that wasn’t what I was talking about here.

I was saying that some genres, at least, are not as open to black readers as they are to whites. Are superheroes one of those genres? That seems to me to be the question. Pointing to another genre (like myths) and saying, this is open to everyone (which is what you did) is neither here nor there in terms of superhero comics. You need ot look to the genre you’re talking about, not to some other genre somewhere else.

““White supremacist” means nothing as applied to superhero comics unless you extend it to all those comics that represented whites as the dominant class– and that means all of them, in all genres. You would also have to extend it to all entertainment that reflects the same proposition, which of course is very nearly everything in the twentieth century.”

This is doubly confused. First — are you saying that somehow most American culture of the 20th century is *not* white supremacist? Because a whole ton of it is. Racism is and has been quite central to mainstream culture in the U.S. (I’m sure you know that…so not sure what point you were trying to make.)

Second, you seem to be really confused about what white supremacy entails. Representing white people as the dominant class is not white supremacist. It’s presenting white dominance as natural and positive that’s the white supremacist part. Do superhero comics do that? Given their emphasis on assimilation and their idealization of law enforcement, I think you can make a good argument that they do. But whether they do or not, the fact that white supremacy is pervasive would not make white supremacy in superhero comics less of a problem. On the contrary, I’d say.

Well what I’d like to say is that my purpose with this essay was to in a way deliver a sense of optimism with the superhero genre when it comes to black characters. I think all the articles posted about them that I listed are very insightful and deliver a buffet for thought, but I didn’t like the statement they leave that the black hero just cannot sufficiently exist in a majorly white guy-produced medium. I couldn’t in any way refute the logic, and it really does apply with All New Cap.

My thing generally is this: Race matters most when it’s directly introduced in the plot. Superhero books are primarily about fight scenes and flashy artwork, and I’m cool with that. When the story actively invites comment of social and culturally relevant issues like who represents America or how can one black hero represent the potential for the black American (Icon), then that’s when analysis gets a cordial invitation. To be real though, I don’t need Static or Mal Duncan or the breezier characters to be more than what they’re set out to be, even if that amounts to very little ultimately. If they interest me on their comic booky concept then I’ll seek them out on that alone. When they act unbelievable within the social circumstances they’re in, then we can talk about how they’re part of the problem. Otherwise I’ll tend to watch/read Static Shock and enjoy the black guy’s Spider-Man and whatever merits that consists of, or indeed lacks.

Thank you for reading and all of the kind words everyone!

I teach a university class on media literacy. Yesterday, the students did an in class exercise where they identified character tropes in their favorite TV shows. I’m at a diverse campus, (we graduate more African American students than almost any university in the country), so roughly 1/3 of the students in this 120 person class fall into that demographic. Anyway, most were fans of a variety of shows, and those who spoke up seemed pretty aware of which shows dealt with the challenges they face day-to-day, and which waved the whole thing off in the name of entertainment. Nobody argued that every show should be a “very special episode” on race, but almost everybody (regardless of race) seemed skeptical of the notion that entertainment is at odds with an accurate portrayal of the African American experience, or at least a portrayal that speaks to that experience on some level. A lot of kids seemed pretty into “Empire” for its ability to do this.

From what I’ve seen of Empire it’s pretty good. It’s very soap-opera-ish, but the acting pedigree puts it over.

Gene, let’s be clear: comics that focus in whole or in part on “The Struggle” as you phrased it can still be escapist. The idea that pop culture that recognizes political Blackness is too much of a downer to be enjoyed strikes me as an absurdity. Again, no one suggests that media invested in whole or in part in an authentic recognition of Black history and culture must, by necessity, be depressing, nor does anyone suggest that Black do not have the freedom of expression other groups enjoy when expressing narratives about themselves in entertainment media.

Frankly I don’t consider The Struggle depressing. It’s about bravery and perseverance and the triumph of the human will. None of that depresses me. Others are free to have their own reactions.

My consistent point here is that it is not possible to seriously include racial difference into the superhero concept; especially if writers treat racial difference seriously. Donovan applied this theory to All-New Captain America #1, and his results speak volumes. I don’t pretend it’s the happiest realization, but it’s honest, and necessary if comic fans of color ever wish to get beyond “stealing all the White people’s superheroes”, as Michelle Rodriguez put it recently.

Whether this makes superhero comics inherently White supremacist or functionally White supremacist is another matter; one I’m trying to address with my next article. Superhero comics, in my view, require Whiteness to operate, and even when a visually Black man dons the star-spangled uniform, they still require Whiteness to operate. I’m less concerned about fun at that point, and more concerned with why that dynamic exists. Hope this clarifies.

The fact that a dedicated superhero enthusiast like Gene sees a discussion of blackness within superhero comics as innately depressing or inimical to the genre is I think evidence for James’ point.

“I was saying that some genres, at least, are not as open to black readers as they are to whites. Are superheroes one of those genres? That seems to me to be the question. Pointing to another genre (like myths) and saying, this is open to everyone (which is what you did) is neither here nor there in terms of superhero comics. You need ot look to the genre you’re talking about, not to some other genre somewhere else.”

The relevance of myths is that we know that separate tribes of varying races created myths about superhuman entities, and that a thunder-god like Shango had for some Yoruba pagans a meaning that is not reducible to sociological commentary, just as Thor had a similar irreducible meaning for Nordic pagans.

Now, if no black readers had ever been entertained by superhero comics, irrespective of whether or not those comics featured black heroes, then you would be right: there could be no meaning-that-you-can’t-reduce-to-sociological factors between superhero comics as perceived by white readers and superhero comics as perceived by black readers. But I notice that no one here has made this claim, and that’s fortunate, because it would be utterly false. However, there has been a lot of talk about Black Readers as if they all conformed to a universal pattern, and that’s tantamount to saying the same thing.

“are you saying that somehow most American culture of the 20th century is *not* white supremacist? Because a whole ton of it is. Racism is and has been quite central to mainstream culture in the U.S. (I’m sure you know that…so not sure what point you were trying to make.)”

I’m pointing out that your rhetoric has no particular relevance to superhero comics, or even to the medium as such. I have not yet seen it stated that there can also be no black westerns or black private eye stories because these also implicate the heroes in the white power structure, but that would seem to be the logical extrapolation.

“It’s presenting white dominance as natural and positive that’s the white supremacist part.”

But unless you can point to a towering mountain of superhero comics that make *explicit* reference to the superiority of whites over all other races– the way that KKK rhetoric does– then you’re just recycling Barthes’ empty argument about the supposed naturalization of the bourgeoise’s values.

“Gene, let’s be clear: comics that focus in whole or in part on “The Struggle” as you phrased it can still be escapist.”

Do you have an example, taken from comic books? Because the parameters you drew in your essay seem to mitigate against ever having any sort of story that did not have a sociological message.

I should specify that I am not opposed to the ideal of keeping characters true to the voices that they should logically have, whatever their cultural origins. But that’s very different from claiming that the superhero genre “requires Whiteness to operate.”

“The fact that a dedicated superhero enthusiast like Gene sees a discussion of blackness within superhero comics as innately depressing or inimical to the genre is I think evidence for James’ point. ”

I haven’t said the discussion of the issues– I assume you mean within the sphere of superhero stroies– would be either depressing or inimical; only that I thought it would be heavy handed to do so all the time, and that I doubted that even black readers wanted to constantly relate to the Struggle while reading for recreation.

Your reading of myths seems hopelessly reductive, to the point of near idiocy. Joseph Campbell…that guy needs to be roundly smacked.

The rest of your discussion also seems largely irrelevant or confused. I’m sure there are black people who enjoy Gone With the Wind. It’s still racist neo-Confederate propaganda. Neo-confederate propaganda, as a genre, might well attract some black readers, but it’s never going to be a genre that is as open to white protagonists as black ones, in part because it’s always going to be a genre that is ideologically on the side of racism and of treating black people as if they’re not people.

So, is that a problem with superhero comics too? You don’t actually engage with the question; it’s all hand-waving and appealing to the fact that some black people like them — which sure, that’s true. But can superhero comics ever become integrated in a meaningful, thoroughgoing way? Can they ever ideologically support a world in which black people are equal and human? As Donovan says, there’s not much sign that they’ve been able to do so yet. And the fact that some black people like Scarlett O’Hara isn’t much of a response, it doesn’t seem to me — unless the goal is to be an apologist rather than actually grappling with the question.

To me the central issue is that superhero fantasies were originally constructed as assimilationist fantasies. That makes whiteness in these comics the goal and the dream. Attached to that, you have the problem that superhero comics are committed to law and order, and law and order in an American context is racialized in a thoroughgoing way. If the awesomest thing you can think of is a superpowered cop, that’s a bleak vision for people who are systematically persecuted by police.

Again, your impoverished view of what it might mean for comics to deal with blackness is depressing, and tends to refute your effort to defend superheroes. James isn’t asking for comics to all be about the struggle. He’s asking for comics which are able to acknowledge racial difference without trying to erase it or police it. And all you can say is, “well, all myths are the same.” You’re default defense of superheroes is a knee jerk erasure of difference; some Joseph Campbell heroe journey bullshit in which non-Western mythologies become adjuncts to some Western professors barmy Key to All Mythologies. We’re all really the same! I.e., read my stories, or, alternately, read your stories as my stories too. You’re just saying that all superheroes have to offer people of color, at best, is erasure and pompous condescension. Which is James’ argument in a nutshell.

Noah, I wish there was a Like button for that last comment.

Here’s the appeal of the superhero/double identity story. You are different, outcast, looked down upon. But secretly, the traits that make you different really mean you’re super. The reason you don’t fit in is because you were meant for better things. If they only knew who you really are, etc.

If you’re telling me that superheroes are intrinsically white somehow, you’ve got to convince me that formula speaks only to white people.

Come off it.

Not to mention that when two Jewish boys created Superman, being Jewish wasn’t exactly “white” in the America of the time.

Superman is not an assimilationist fantasy, he’s a superiority fantasy. Superman is not subject to human law or the laws of physics. When he assimilates, he’s Clark Kent saying, “Gee, Lois, would you like to go on a date sometime?”

The appeal of the superhero concept is not relevant when discerning the racial nature of the superhero concept. People of color far and wide enjoy media that lampoons and denigrates them; corporate hip hop would not exist if rappers who used anti-Black racial epithets in their music faced boycotts from the Black community.

The difficulty in this conversation is that many superhero comic fans regard the superhero as a concept with universal appeal. Appeal is not the point: the relevant question asks whether race and gender difference can be included in superhero narratives, more than just superficially, without utterly breaking the narrative foundation that superheroes require. The answer is no.

And that’s why every Black superhero from Marvel and DC ranges from inauthentic palette swapped White man with darker hued ink to outright racial hate crime. That’s how we end up with Jason Rusch in a chicken suit by his solo comic’s sixth issue. That’s why John Stewart does more good with his Green Lantern ring on alien worlds than among his own people. That’s why most every Asian superhero knows some martial art, and why Ming-Na Wen’s Agent May on Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. is such a dragon lady stereotype she opens doors with her feet. Superhero comic media requires Whiteness to operate; race and gender difference in this material is viewed through that racial construct. Stereotypes abound.

Put another way (with a nod to Spike Lee’s Malcolm X), you don’t get to Luke Cage without the White man’s permission. It’s immaterial that Cage’s portrayal over the years resembles blaxploitation protagonists from the 1970’s, or that those portrayals gained some popular support among Blacks then and now. The point is that Cage reflects other people’s interpretation of what a Black man is; in order to operate as a superhero, Cage’s sensibilities about law and order, the pursuit of justice, and race relations generally have to dovetail with mainstream Marvel heroes, and a writing/ publishing structure designed to sell White male power fantasies to a mainly White male audience, in the company’s estimation. Luke Cage isn’t Sweet Sweetback. With most writers he’s brawny, strong, and stupid, but enough of a foot soldier to attack whomever Steve Rogers or Nick Fury tells him is the bad guy. This again leaves him as likely to jab Skrulls as Harlem purse snatchers.

Michael, Gene, everyone: what matters here is how visual race and gender minorities are used in comic books. Superheroes require Whiteness to operate: if this genre was truly about universal appeal, then it should be easier to sell race and gender superhero comics. It isn’t, as Diamond’s sales figures routinely attest.

The fact that Jewish wasn’t quite white is why it’s an assimilationist fantasy. The alien comes to America and turns into the most perfect Aryan hero. The skinny nerdy guy gets a shot and becomes the American super soldier. It’s about difference being assimilated.

It’s about outcasts getting to be awesome — but the awesome thing they get to be is cops. That’s what makes it assimilationist; it’s about the despised other becoming the one who enforces the status quo, not least by policing the “others” who aren’t model minorities.

Does that have to be the way it works? Arguably it wouldn’t have to…but in practice there are precious few counter-examples. Even creators that expressly set out to challenge the paradigm (Christopher Priest’s Black Panther, Captain America Truth) have a lot of trouble with it, or end up capitulating to an assimilationist and/or law and order model.

I still want to read the Miles Morales Spider-Man, and Icon…maybe one of those works. I don’t have high hopes though.

I think Ms. Marvel works with the assimilationist fantasy in smart ways; it’s still about assimilation, but self-consciously so, and as a result I think it avoids some obvious pitfalls, and comments on others, as when Kamala’s first superhero identity is blonde and Caucasian, and then she rejects that. It’s definitely limited — there’s not much sense of the fact that Muslim’s in the U.S. might distrust, and have real reason to distrust, the police. But still, it handles race pretty well, IMO.

That’s why I linked to that Ajala appreciation piece: the idea that this setting’s equivalent of SHIELD is not a race-bent super agency, but a community-built defense organization is lovely. Ajala doesn’t end up working for the military-police complex, nor is her heroic genealogy retconned into such a thing (as has happened in USM with Bendis’s revelation that Miles Morales’s father was a reluctant agent of SHIELD).

“Your reading of myths seems hopelessly reductive, to the point of near idiocy. Joseph Campbell…that guy needs to be roundly smacked.”

Says the dedicated reductionist. But I imagine that Joseph Campbell is no more responsible for my sins than Sigmund Freud is for yours.

The example about myths is purely illustrative, but since you don’t get the parallel, I’ll drop it.

??? I don’t agree with Freud on everything, but I’m definitely very influenced by the Freudian tradition of criticism.

I don’t see that tradition as particularly reductionist. It tends to argue that authors mean more than they say (and/or say more than they mean.) It’s a criticism of plenitude. People resist it because they dislike the implications of excess, in my experience.

“it’s always going to be a genre that is ideologically on the side of racism and of treating black people as if they’re not people.”

Based on what? Early history? If the comics medium’s early history is so hopelessly implicated in racism that it can never change, then why should one hold out any hopes that the culture that produced them can change?

“But can superhero comics ever become integrated in a meaningful, thoroughgoing way?”

And you’re skirting the question as to who decides when they have reached that point. That’s because it’s a question with no answer, all you can speak to is whether you, personally, feel that they have attained utopia– although someone else may well disagree.

Your comparison of superhero comics (again, we seem to be talking only of them and no other pop-fiction) to GONE WITH THE WIND is answered by my earlier comment that the former is not *overtly* implicated in racism as is the latter. I find your comparison of one 20th-century novel to an entire genre just as ridiculous as you find my comparison of myths to superhero comics, BTW.

“You’re just saying that all superheroes have to offer people of color, at best, is erasure and pompous condescension.”

Nope, that’s all you. It sure is funny how the people you debate, Noah, are somehow always taking a stance that proves your point. I have not endorsed erasure of racial identity; I have consistently argued that there are commonalities in the enjoyment of fiction that go beyond a narrow conception of racial identity. When I point out holes in your arguments or those of others, that does not constitute being against all the ideals for which you purportedly stand; merely against your bad logic in sussing them out.

And please– no more Campbell comments. Your screed reads like something you picked out of Wikipedia.

J. Lamb. you say:

“The point is that Cage reflects other people’s interpretation of what a Black man is; in order to operate as a superhero, Cage’s sensibilities about law and order, the pursuit of justice, and race relations generally have to dovetail with mainstream Marvel heroes, and a writing/ publishing structure designed to sell White male power fantasies to a mainly White male audience, in the company’s estimation. Luke Cage isn’t Sweet Sweetback.”

OK, but you also say:

“corporate hip hop would not exist if rappers who used anti-Black racial epithets in their music faced boycotts from the Black community.”

Correct me if I’m wrong, but didn’t SWEET SWEETBACK’S BAADAAASS SONG sell itself via promotion that used an “anti-Black racial epithet?” And whether that slogan was conceived by white or black persons, did it convey “anti-Black” sentiments to its contemporary audience?

I’ll try to sum this up quickly. You think that Luke Cage, for example, is implicated in white values because his values aren’t sufficiently distinguished from theirs. I think that’s a gross oversimplification because it overlooks the fact that popular fiction deals with larger-than-life conflicts, and those are not neatly reducible to the particular social concerns of any given group. Thief X wants to steal Y; Tyrant D wants to conquer country E. These situations do not reflect “white values:” they have wide appeal because they reflect basic human needs for security and homeostasis.

I’m sure there are any number of complaints you can make about the treatment of blacks or Asians by white writers; maybe some or all of them are justified. But they do not prove the existence of some monolithic “white value system.”

“I don’t see that tradition as particularly reductionist. It tends to argue that authors mean more than they say (and/or say more than they mean.) It’s a criticism of plenitude. People resist it because they dislike the implications of excess, in my experience.”

Are you saying that the Freudian tradition is a criticism of plenitude, or the reaction against it is?

In any case, Freud was a reductionist because he boiled all aspects of the human psyche down to physical reactions or patterns of entrainment. I’ll even resort to Wikipedia myself this time:

“Reductionism is a philosophical position that holds that a complex system is nothing but the sum of its parts, and that an account of it can be reduced to accounts of individual constituents.”

GWTW is actually part of a broader genre of neo-Confederate apologies, which I think constitute a genre, and quite a popular one (GWTW remains very popular; Birth of a Nation was hugely popular in its day.) So…not just one novel.

I think your cutting out bits of my comments? I’m not entirely certain that superhero genre is in fact white supremacist, or that it has to be. I think it’s an open and reasonable question. If you want to disprove it, it seems like the thing to do is offer counterexamples? I have some counterexamples myself, though they tend to be towards the edges of the genre. But instead, you just keep reiterating that of course superhero comics aren’t white supremacist. Here, you do it again:

“Your comparison of superhero comics (again, we seem to be talking only of them and no other pop-fiction) to GONE WITH THE WIND is answered by my earlier comment that the former is not *overtly* implicated in racism as is the latter.””

That’s, like, your opinion, man, as they say. And it’s not a ridiculous opinion! I’m willing to hear you argue it. But you haven’t done so. You just keep saying, that the contrary opinion must necessarily be wrong because…why? You say you’ve dropped the comparison to myths. That is a wise move on your part, because that comparison was stupid. But you don’t offer anything else. Yes, of course, different folks are going to come down in a different place on these sorts of things — but opinions are supposedly based on some sort of evidence, or some kind of reading.

If superhero comics aren’t white supremacist, show me a superhero comic that isn’t white supremacist, you know? Give me a reading of a comic that you think challenges the default whiteness of the genre. Ideally, to convince me, the comic would push back against the assimilationist logic of superheroes, or against the law and order genre default, or recognize the way that law and order genre default is an implicit threat against black people. My contention is that it’s really difficult to find superhero comics that do this. I think Grant Morrison’s run on Doom Patrol does, arguably, at least to some extent, though it’s really more focused on disability issues, which turns blackness into a disability in some ways, which isn’t ideal. I’ve been looking but haven’t really found much else within mainstream superhero comics. So…provide a counterexample, if you’ve got one, and we can talk about it. Otherwise it’s just handwaving and huffy assertions of outrage that anyone could think such a thing, since not everyone everywhere thinks it.

You’re a smart guy; set aside your knee-jerk defense of your chosen genre as some sort of holy grail, and engage with the issue at hand.

Oh, and re other pop fiction…I’m happy to talk about other pop fiction and race. If you’re point is superheroes aren’t any worse than anything else…I don’t think that’s exactly true, first of all, and second of all, so what? Why would we want to grade on a curve for racism, anyway? Racism is pretty prevalent, but that doesn’t mean that some specific expression of racism is okay.

Gene, I get why Freud is called a reductionist. The critical tradition coming out of it is a tradition of plenitude in general, though. People dislike it because it comes up with readings that are too excessive, not because it’s always the same reading.

“it overlooks the fact that popular fiction deals with larger-than-life conflicts, and those are not neatly reducible to the particular social concerns of any given group. ”

You might as well be one of those folks whining because #blacklivesmatters leaves out white people, Gene.

The appeal to universal human values is a tactic frequently used to erase the concerns of marginalized groups. The perspective of the majority is seen as natural and universal. In your world, everyone has the same relationship to tyranny and crime; those relationships are universal and natural. White values don’t exist because they’re universal values.

Are you unfamiliar with these discussions? This is pretty basic stuff. I’m surprised you don’t have a better response to it than just, “I speak for all mankind”.

It does explain why you’re unable to actually engage with the issue at hand, and can’t do readings of individual comics though. All stories are the same story; all superhero comics just reiterate the same universal narrative. The very idea of thinking about treatments of race are verboten, since race isn’t sufficiently universal to “count” as a thing worth talking about. Again, you just seem to reify the point James is making; your commitment to superhero comics is based in a pseudo-mythological reading which structurally erases black people.

Noah’s already discussed the problems with the notion that superhero comics grapple with universal themes; I’ll just add that I believe superhero comic genre conventions cause the less-than-desired treatment of women and people of color in comics, not the racial identities of the authors themselves.

Superhero comics do not present universal stories, Gene. If you’re a street level superhero like Luke Cage, Tyrant D’s dastardly plan to conquer country E should not matter to you at all. When you’re drafted by Nick Fury to commit off-the-books regime change in Latveria, you should have a problem suiting up alongside Wolverine, Captain America and others, no matter how beautifully Gabriele Dell’Otto paints your likeness.

Really, this assumptive universality of the morals of superhero comic narratives is mistaken. More than Daredevil, Cage should express severe reservations about his involvement in battles with Skrulls. The Superhuman Registration Act could have been an opportunity for Cage and heroes like him to leverage their compliance with that statute into financial subsidies for populations they consider important; instead Cage bellows about the capes as a tradition, outside the vagaries of public opinion. (I’m paraphrasing; Cage abhors polysyllabic verbiage, since he’s an inauthentic caricature of a strong Black man.) Even then, Cage has no voice that demands respect from his White comrades; in Civil War #5, Captain America’s admonishment (“Quiet, Cage. I’m thinking.”) displays the anti-registration pecking order in stark relief for all readers.

I contend that if superhero comics really served as the universalist narratives you promote Gene, then Luke Cage would not be such an illogical, irredeemable sellout on race. He would care nothing for Steve Rogers’ pissing match with Tony Stark. But in White male power fantasies like superhero comics, Whiteness reigns supreme– even to Black characters who should have their own concerns. Hope this clarifies.

You know, I hadn’t thought of it, but I think the crossover nonsense actually contributes to the problems. Luke Cage and Black Lightning were both at least sort of presented as having a particular investment in the black community, but the inevitable gravity of the continuity porn drags them into joining some stupid super team, or teaming up to battle the cosmic threats or what have you. The shared universes tend to treat most supercharacters as background decoration for the few important (read popular/recognizable) heroes; as a result black heroes like Cage are casually undermined and humiliated as a matter of course.

The Millenium line handles that better…as does the Heroes television show, sort of. Not that either of those things is ideal (Heroes is filled with invidious stereotypes) but the particular dynamic you describe with Luke Cage at least seems avoidable when you move away from the Marvel/DC universes where all the main properties are white guys.

“Cage should express severe reservations about his involvement in battles with Skrulls.”

I feel like some of these ideas would come off as silly if someone tried to use them in a story. Like, the Skrull crossover was some sort of Invasion of the Body Snatchers ripoff. I’m trying to imagine a version of Invasion of the Body Snatchers where there’s a black guy who’s all like, “I should be protesting in Ferguson, not fighting Body Snatchers!” and that movie sounds like a comedy.

Pallas, two points.

1) It’s a fair argument to assert that eighty-odd years of superhero narratives produce genre conventions at odds with the ideas about so-called Black superheroes I present. Put another way, maybe the reason some of these ideas would come off as silly if used in a story is because writers of superhero comics never use them in stories. We never see authentic characters of color in superhero comics; at best, we have pale interpretations of minority sensibilities, whitewashed by the genre’s conventions.

2)Luke Cage would not necessarily default to protesting in Ferguson if he wasn’t knee deep in Skrulls during Secret Invasion. There’s an assumption that Black superheroes set priorities in a very binary sense. If the option is fighting Body Snatchers or protesting in Ferguson, that’s obviously a false choice. I realize that idea was slightly tongue-in-cheek, but the danger with the superhero concept remains it’s failure to take non-White, non-male, non-straight, non-adolescent humanity seriously. That’s how we get a perversity like Luke Cage to represent Black masculinity in comics to begin with.

Stuff like this is why I suggest that the superhero concept cannot handle race. Or gender. Or sexual orientation. Or any identity difference. If everyone wants to punch Skrulls in the face, human difference does not matter. That’s a problem for characters designed to represent difference in panel.

“If everyone wants to punch Skrulls in the face, human difference does not matter.”

In the original Marston/Peter Wonder Woman, the plot wouldn’t have involved punching Skrulls in the face. It would have involved teaching the Skrulls the virtues of love and setting up a female Skrull matriarchy so the male skrulls could live their lives in happy loving submission.

I think superhero stories can be somewhat flexible…but that does involve writing stories which push against the genre defaults. That is, yes it would be stupid to tell a story about hitting Skrulls in which Luke Cage wants to deal with Ferguson — but what that means, it seems like, is that you need to figure out a way to tell different stories if the superhero genre is going to include black people.

Which is going to be extremely difficult as long as superheroes remain a primarily commercial genre.

The question is can any Superhero be true to the black experience ? Either he/she embodies old struggles for identity in two worlds or is completely above the daily struggle for existence which is the condition of most black Americans. At least comics are trying to embrace the new dynamics. For kids within that demographic there appears to be hope. We who have responded to this seminal question are all avid readers because comics were the first to see the need for heroes of color and have been at the forefront of societal change. Wno could have imagined a black “Cap” or a black “Spiderman” as this genre was created ? I know we have wondered not if but when…

“GWTW is actually part of a broader genre of neo-Confederate apologies, which I think constitute a genre, and quite a popular one (GWTW remains very popular; Birth of a Nation was hugely popular in its day.) So…not just one novel.”

The context of your remark about GWTW was that some black readers may have enjoyed it, and I responded by saying that the comparison of one novel with overt racial content isn’t fair against an entire genre of comics, some of which include some racial content and some that don’t– though, as I said earlier, even most of the comics that use lazy stereotypes don’t have a political agenda. So even if you had made a direct comparison between all Confederate-apology fiction and all superhero comics with racial content, the comparison fails.

“But you haven’t done so. You just keep saying, that the contrary opinion must necessarily be wrong because…why?”

Since you’re one of those claiming that the superhero genre is rife with white supremacist content, the burden of proof falls on you, not me, to provide specific examples. So far you’ve asserted the proposition in a bland, somewhat non-committal manner, and that’s about it.

“You say you’ve dropped the comparison to myths. That is a wise move on your part, because that comparison was stupid.”

I’ve dropped it because you didn’t understand it, so there was no point in pursuing it, just as I said in my comments. But the principles behind the comparison remain valid, and were reiterated in my comments to J. Lamb re: the appeal of popular fiction across racial barriers.

“Give me a reading of a comic that you think challenges the default whiteness of the genre. Ideally, to convince me, the comic would push back against the assimilationist logic of superheroes, or against the law and order genre default, or recognize the way that law and order genre default is an implicit threat against black people.”

But I would never bother addressing such phony-baloney constructions. None of these ideas relate to the content of the stories; all of them are just you (and others) trying to project sociological myths upon material that can’t support such abstruse interpretations. You’ve already made up your mind that such phantasms as “default whiteness” pervade the genre, so what good would a reading of any one comic do?

Rather, I’m opposing one concept with another: against the idea that black readers can only be defined by blackness, I propose the idea that they and all humans share a vast storytelling heritage; one that goes far beyond any particular political grievances. You’ve made clear that you consider this an erasure of difference; I see it as a confirmation of difference within a greater sphere of basic similarity. That’s all I wanted to get out there, and that’s probably all that can be said on the matter.

“Oh, and re other pop fiction…I’m happy to talk about other pop fiction and race. If you’re point is superheroes aren’t any worse than anything else…I don’t think that’s exactly true, first of all, and second of all, so what? Why would we want to grade on a curve for racism, anyway? Racism is pretty prevalent, but that doesn’t mean that some specific expression of racism is okay.”

Still willfully misreading, I see. For someone who complains about selective citation of comments, you’ve gone me one better. The point remains not to endorse racism in other genres but to put your feet to the griddle about why you’re finding it only in superheroes. If you want to state for the record that you’re just using superheroes as shorthand for all popular genres, that would be defensible in line with your other statements. I’m guessing that you won’t take that position, though.

“The critical tradition coming out of it is a tradition of plenitude in general, though.”

Are you quoting someone in this passage? I googled Freud and plenitude and got sites ranging from Lacan to Jung. I don’t want to argue the definition here, but I may be able to use it somewhere.

‘The appeal to universal human values is a tactic frequently used to erase the concerns of marginalized groups. The perspective of the majority is seen as natural and universal. In your world, everyone has the same relationship to tyranny and crime; those relationships are universal and natural. White values don’t exist because they’re universal values.

Are you unfamiliar with these discussions? This is pretty basic stuff. I’m surprised you don’t have a better response to it than just, “I speak for all mankind”.’

Just because you claim that it’s a tactic does not mean that that’s the whole ball of wax. If one politician lies to you, does that mean that every politician will lie to you?

I’ve seen dozens of similar Mickey Marx discussions, and I mentioned one of the Mickey Marxists in my first post. so yeah, I’ve heard the best the MM’s have to offer, and still say that Emperor Roland and his relations aren’t wearing any clothes.

“It does explain why you’re unable to actually engage with the issue at hand, and can’t do readings of individual comics though. All stories are the same story; all superhero comics just reiterate the same universal narrative. The very idea of thinking about treatments of race are verboten, since race isn’t sufficiently universal to “count” as a thing worth talking about. Again, you just seem to reify the point James is making; your commitment to superhero comics is based in a pseudo-mythological reading which structurally erases black people.”

What I’ve *actually* said is that black people are not purely defined by their sociological condition. That doesn’t erase difference, though I can see why an ideologue would want to claim that it does.

“Since you’re one of those claiming that the superhero genre is rife with white supremacist content, the burden of proof falls on you, not me, to provide specific examples”

Nope. I’ve written like ten articles about it; Donovan links a couple. James has articles too. You could read them. Or not. But don’t pretend that there’s no case being made just because you’re too lazy to check back links.

“You’ve already made up your mind that such phantasms as “default whiteness” pervade the genre, so what good would a reading of any one comic do? ”

But I haven’t. I’m happy to consider counter examples, and offered some myself. It’s you who’s convinced that everything in the genre works the same, man, not me.

“I propose the idea that they and all humans share a vast storytelling heritage; one that goes far beyond any particular political grievances.”

Right; that storytelling heritage being one in which law and order is righteous and tyranny means the same thing to everyone. Those are political stances; claiming they’re not just erases folks you don’t agree with, and basically the entire history of black struggle in this country.

Re: other pop genres. I’m happy to talk about them. I’m talking about superheroes now, though. If you have a pop genre you think doesn’t have problems with white supremacy, go ahead and talk about it.

Romance is I think overall whiter than superhero comics in terms of sheer percentage…but there are black romance novels. The couple I’ve read are by Beverly Jenkins and Alice Randall (arguably a romance)…oh and I’d count They’re Eyes Were Watching God. I would say that those all present black people as people without erasing racial difference, and also without really having to challenge or undermine genre tropes. So, I think, at least from what I’ve read, that romance is casually white, rather than white supremacist in terms of its genre tropes.)

Sci-fi is arguably white supremacist in a lot of ways initially, but there’s been a lot more work done by both white and black creators to undermine that than is the case with superheroes.I think the same goes for fantasy, more or less (though I haven’t thought that through as much.)

Not quoting anyone re: Freud; that’s just my impression. Quote it if you dare!

“Stuff like this is why I suggest that the superhero concept cannot handle race. Or gender. Or sexual orientation. Or any identity difference. If everyone wants to punch Skrulls in the face, human difference does not matter. That’s a problem for characters designed to represent difference in panel.”

And I’ll pass over the simplistic objections to universality to re-iterate the question that still hasn’t been answered: why is the “superhero concept” particularly vulnerable to this? In these comments you’re had every opportunity to place the entirety of “white pop culture” in the docks, and you’re still talking as if there’s something especially degrading about the black superhero, as opposed to the black cowboy or the black P.I. Doesn’t Shaft end up supporting the status quo by knocking off white mobsters, since white audiences (at least those without Mob ties) will consider these appropriate targets for vigilante action?

Is it the disconnect between street-level action and fantasy-tropes that bugs you? Does your argument also apply to Lando Calrissian, even though he lives in the clouds rather than on the streets?

Oh…and turning a discussion about race into Marx…again, compulsively erasing black people doesn’t shore up your argument.

“Nope. I’ve written like ten articles about it; Donovan links a couple. James has articles too. You could read them. Or not. But don’t pretend that there’s no case being made just because you’re too lazy to check back links.”

Yeah, I’ve heard about the essay in which you downgraded Milestone but only read STATIC. That’s the only one cited above, so you could’ve easily said, “Check this one out for my position.” That omission seems like laziness on your part, but whatever.

“But I haven’t. I’m happy to consider counter examples, and offered some myself. It’s you who’s convinced that everything in the genre works the same, man, not me.”

Nope, I’ve said, in part, that there is content in superhero and other forms of pop culture that can’t be reduced to racial and/or sociological content, and that some of that content addresses basic human needs for security and homeostasis. By saying that this reduces down to the theme of “law and order,” you’re oversimplifying those basic human needs into a convenient sociological matrix.

You know, if you can’t be bothered to read backlinks, you could respond to James’ discussion about Luke Cage. His reading seems pretty damning to me. Do you have an alternate reading? Do you agree the treatment of Cage is poor, but believe other portrayals of black superheroes work better?

OK, since you repeatedly ask– and I suspect I can guess why– here’s an essay by me on a pop-fictional treatment of blackness that is not limited to blackness. Enjoy cutting it up.

http://arche-arc.blogspot.com/2013/01/racial-non-politics-in-django-unchained.html

It’s not clear from James’ post how much Cage he’s read. I can’t comment on a lot of the modern stuff, just the sort of stuff I referenced, like Luke Cage going toe to toe with Doctor Doom. If both debaters haven’t read the same material, there can’t be a worthwhile discussion.

Yeah; I would say portraying Tarantino as some kind of great humanist figure who thinks outside the usual binaries because of the character of Samuel Jackson is pretty wrong-headed. The sweeping strawman version of all (all?) readers of blaxploitation films does a lot more work for you than it should, I’d say.

I guess it fits with your general thrust, though. Universal humanity is a fit subject for art; politics is not. And that’s true even for neoConfederate tropes for you, as it turns out, so my earlier suggestion seems pretty well proven.

You should read Pierre Bayard’s lovely book about not reading; you shouldn’t be afraid to engage in discussion just because you haven’t read something. James provides a nice synopsis, I think.

“We never see authentic characters of color in superhero comics; at best, we have pale interpretations of minority sensibilities, whitewashed by the genre’s conventions. ”

See that’s where I strongly disagree, if we’re being precise. I listed the Robertsons as authentically black in the essay, and others have repeatedly brought up Kamaka Khan. I follow much of your logic J, but if we’re going to have he conversation I don’t think it does any good to write off every single non-white character in superhero comics as a pale imitation. That’s just not true.

“If superhero comics aren’t white supremacist, show me a superhero comic that isn’t white supremacist, you know? Give me a reading of a comic that you think challenges the default whiteness of the genre. Ideally, to convince me, the comic would push back against the assimilationist logic of superheroes, or against the law and order genre default, or recognize the way that law and order genre default is an implicit threat against black people.”

Associating superheroes with law and order is a somewhat limited and simplistic view of the genre. It may certainly apply to comics like Spider-man, but that ignores counter- examples such as stories where the cops are after Spider-man because they think he’s evil.

One of Batman’s biggest influences was Zorro, who isn’t white. From what I remember of Zorro he’s a sort of Robin Hood figure, so probably not on the side of law and order.

The X-men often find themselves battling government sentinel programs, so I don’t see how they can be said to be on the side of law and order and they aren’t always policing other mutants such as you discussed Noah, though of course it depends on the story.

Grant Morrison largely presented them not as a metaphor for race at all, but as sort of utopian idealists versus the square normal society. Been a long time since I read it, but when they say to the military “We’re not subject to human laws or monkey politics” I think they are basically saying “We’re utopian revolutionaries who are following our own ideals.”

Characters like Buffy fight supernatural creatures who probably don’t stand in for criminals, metaphorically. They probably represent mundane adolescent cruelty if they have to represent something.

Card Captor Sakura fights cards which apparently are spirits run amuk, so its kind of man (or girl) versus nature.

When the Fantastic Four fight Galactus, the closest metaphor is probably that of a natural disaster such as a meteor coming to earth to wipe us out. It’s not about law and order.

Frequently the villain in superhero stories are a version of an evil dad or “the man”. Even with a authority figure like Nick Fury, there has to be an even bigger “the man” for him to fight, which is why he fights the Shield council in the Avengers film and the second captain America movie.

Hellboy fights an evil daddy figure Nazi: Hellboy can’t pass for white- incidentally, he’s a big red monster.

Teen heroes often fight adults who are evil, or who just don’t understand kids. When Raven has to face her evil Dad who wants to conquer the world, you may claim its minorities policing minorities, but surely the more direct and relevant reading would be a kid finding friends and coping with parental abuse with their help.

Villains like Ultron who provide a man versus machine theme probably have roots in Frankenstein, who is not about America assimilation and probably not about race relations. It’s either fear of technology or some sort of father versus son theme. Ultron calls Ant Man father, Frankenstein has a similar dynamic. Man verse monster and father verse son is not a law and order theme.

Hulk is wanted from the military and believed to be a dangerous monster, and sometimes he is. He’s not associated with law and order, but is a fugitive on the run.

The cops go after Swamp thing for violating an unjust sodomy law in Moore’s swamp thing. Swamp thing can’t pass for “white” he’s a big green monster.

When the FBI go after Promethea her friend says “What are you looking at. This is nothing new. They’re killing witches!” She’s a radical pagan demigod hardly associated with law and order in that plotline.

Thanks Pallas! That’s a lot of examples; don’t know that I have time to go through all of them, but…a number of them (like Spider-Man being attacked by police) are predicated on the idea that opposition to the police is opposition to law and order. I don’t think that’s true. Rather, superheroes function as a kind of paramilitary right wing law and order force; they’re doing the dirty work of justice that even the police can’t do. That’s a lineage that goes back to the KKK; I don’t think it gets out of the dynamic I discussed. I think that applies to a lot of the lone badass against the system narratives too. One exception I can think of is Justice, Inc, by Andy Helfer and Kyle Baker; in that case the system in question is a recognizable version of the U.S. government, and the government is evil specifically because it’s sexist, racist, and colonialist. I hadn’t thought of that comic in awhile; it’s very good — though not exactly a superhero comic.

Hulk’s initially (and still later metaphorically) a black skinned animalistic out of control evil monster.

I think the way Cyborg is used in Teen Titans is generally not very thoughtful (to speak to yoru Raven/Trigon discussion.)

I think vampires in Buffy are adolescent cruelty, but it’s also a criminalizing of adolescent. A vision of evil adolescents who have to be killed because they are homicidal racial others has racial connotations.

Sentinel stories: Days of Future Past at least is a mess in terms of race. They fight government robots, but the story goes out of its way to say that the way you fight government robots is by showing your fealty to the government and protecting the white establishment. That’s kind of generally the thing with the Sentinels isn’t it? They’re pseudo government program, but it’s the excesses of one whacko, and there’s never a suggestion that the actual U.S. government is in some ways actually at its heart racist and horrible. Is there? I haven’t ever seen that story, though maybe it’s out there; in general the Sentinels just function as supervillains.

Card Captor Sakura is a really smart counterargument. It’s been a long time since i read those…but I think Sailor Moon adn other magical girl superhero comics also work interestingly… Of course the heroes are Japanese, not white, and its more fantasy challenges than criminals…it seems like they avoid the racial dynamic of black/white in part by just being off to the side of American racial issues, but I think they are still a portrayal of non-white heroes that get around most of the issues James discusses.

John Rieder provides a pretty awesome reading of Frankenstein which relates the story to colonial concerns. Here’s another:

http://www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/ENGL403-3.1.6-Race-and-Otherness-FINAL-PR.pdf

Stories about evil monstrous others don’t unsettle the white paradigm, I don’t think.

Okay, need to go!

‘Rather, superheroes function as a kind of paramilitary right wing law and order force; they’re doing the dirty work of justice that even the police can’t do ”

Well this reminds me that the original Superman was apparently a left wing vigilante fighting for new deal democrat values. In the Superman serial “Clan of the Fiery Cross” he fights the KKK. In the 1951 film “Superman and the Mole Men” the town folks are scared of the innocent mole people, and form an angry mob to kill them. Superman stops them. It’s actually about deescalation of violence.

Wikipedia says “The sympathetic view of the strangers in this film, and the unreasoning fear on the part of the citizenry, has been compared by author Gary Grossman to the panicked public reaction to the peaceful alien Klaatu in the film The Day the Earth Stood Still, which was released the same year. Both films have been seen retrospectively as a product of (and a reaction to) the “Red Scare” of post-World War II. “

Just to add on to the manga mentions, much of Dragon Ball consists of villains reforming themselves into heroes. It sometimes either doesn’t apply or isn’t executed well, but it’s consistent enough in the series that it’s reoccurring to where half if not most of the heroes were all villains at one point.

Pallas, it’s been a long time since I saw Superman and the Mole Men. “Don’t you know if you go around shooting at shadows, someone’s bound to be hurt!” is a line I remember for some reason. And there was an anti-KKK series in the comics too, I think…

I guess the issue with those things is superman’s status as anti-fascist fascism. Yes, he’s against the KKK — but he’s also the Superman, perfect white masculine embodiment of America. If the ideal white American is the bullwark against racism, where does that leave black people? I think Truth gets at this; haing Captain America come in at the end and solve all the problems and beat up the evil racists is anti-racist in some sense, but it doesn’t get out of the white savior dynamic, and it makes all the real heroes white.

The anti-KKK Superman storyline was actually from the radio program in the late ’40s. It’s credited with having a decisive role in ridiculing and enfeebling the Klan.

“Oh…and turning a discussion about race into Marx…again, compulsively erasing black people doesn’t shore up your argument.”

I brought up Marx because you explicitly asked me if I was aware of discussions regarding cultural erasure. You said (and asked):

‘The appeal to universal human values is a tactic frequently used to erase the concerns of marginalized groups. The perspective of the majority is seen as natural and universal. In your world, everyone has the same relationship to tyranny and crime; those relationships are universal and natural. White values don’t exist because they’re universal values.

Are you unfamiliar with these discussions? This is pretty basic stuff. I’m surprised you don’t have a better response to it than just, “I speak for all mankind”.’

Whether or not you can find this in Marx himself, the same sentiments permeate Marxists. Barthes is one. Derrida seems to be more of a “fellow-traveler” than a hardcore Marxist, but I don’t see much difference between his objections to logocentrism and your objections to Campbell.

By the way, since Campbell is accused of drowning the particular in the universal, that would be the opposite of his being “reductive,” as I believe you termed him. Freud would be reductive because he reduces the hypothetical universals to particulars; Campbell, going from particular to universal, might be called (after Jung) “amplificative,” assuming anyone desires an exact parallel. Or you can just say it’s BS and forget the parallels, I suppose.

“Yeah; I would say portraying Tarantino as some kind of great humanist figure who thinks outside the usual binaries because of the character of Samuel Jackson is pretty wrong-headed. The sweeping strawman version of all (all?) readers of blaxploitation films does a lot more work for you than it should, I’d say.”

I didn’t call Tarantino a “humanist,” since that word is loaded for bear, but I did and would still call him a moralist. I also demonstrated that he does think beyond the binaries, and I don’t think you can prove otherwise. You’re free not to find his line of thought pleasing, of course.

“The sweeping strawman version of all (all?) readers of blaxploitation films does a lot more work for you than it should, I’d say.”

I don’t get the “strawman” remark. I said that they are escapist in tone, which they are, but that’s certainly not a minus in my book. Otherwise, why would I be defending the basic integrity of escapist content like having Luke Cage fight Doctor Doom (or the Skrulls, for that matter)?

“And that’s true even for neoConfederate tropes for you, as it turns out, so my earlier suggestion seems pretty well proven.”

I can’t quite decipher this sentence. The only neoConfederate trope I see in DJANGO, and the only one I mentioned, is that of the black slave crying over his dead master. Maybe you don’t believe, as I do, that Tarantino undermines the intentions of the original trope. Was that your point?