Death is a hard box to climb out of. But that’s how Harry Houdini made his living. The escape artist has been dead eighty-nine years, and he’s still scraping at the lid.

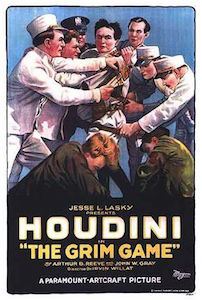

His latest trick is The Grim Game, a 1919 silent film serial thought lost for decades. Turner Movie Classics is ressurecting it for a second world premier duing the TMC Classic Film Festival the weekend of March 28. It includes the near death of Houdini’s double, Robert E. Kenndy, who dangled from a rope as two stunt planes accidentally collided before gliding to crash-landings. When Houdini later described the film shoot, he substitued himself for Kennedy. He’d been performing that sort of body switch his whole career.

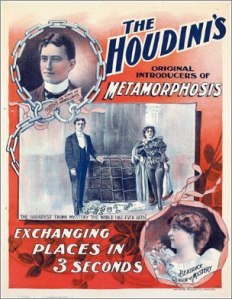

Houdini’s first trick was called Metamorphosis, and he started performing it in 1893. I saw a version of it on my sister’s high school stage when I was fourteen. A magician is hand-cuffed, tied into a sack, and padlocked into a crate. An assistant stands on the crate, lifts a sheet above her head, and when she drops it on the count of three, the magician is standing in her place. When he unlocks the crate, there she is, sack-tied and hand-cuffed. When Harry Houdini performed it with his wife in Dusseldorf in 1900, a reporter explained how it’s done:

In dematerialization, or the phenomenon of self-dissolving, the force of attraction and cohesion between molecules is overcome. As has been proven through innumerable examples, every body can in this way be brought in an aetheric condition and therefore, with the help of an astral stream, be transported from one place to another with incredible speed. In the same instant the power used for dematerialization is retrieved; the aetheric pressure again shows the molecules, which again take on their original local and former shape.

Although he started his career as a medium, the only superpower Houdini ever claimed was “photographic eyes,” and that only worked for memorizing locks. He did train himself to breathe so “quietly” he could last an hour and half in a soldered coffin. Other skills involved inserting and removing objects from his throat and anus. Mostly though he understood pain.

Germany called him uncanny, a Napoleon, a limitations-defying Faust. Russians debated whether his supernatural powers were evil. Spiritualists in the U.S. and U.K. applauded his act, “one of nature’s profoundest miracles,” lamenting that audiences mistook it for just “a very clever trick.” Drama queen Sarah Bernhardt asked him to grow back her severed leg. “She honestly thought I was superhuman,” Houdini told reporters.

He also told reporters that “it is only right that what brain and gifts I have should benefit humanity in some other way than merely entertaining people.” Jerry Siegel was two at the time, but Clark Kent would similarly decide “he must turn his titanic strength into channels that would benefit mankind.”

Houdini played a superhero of sorts in his film serial The Master Mystery, shot the year before The Grim Game. A mild-mannered lab tech is secretly Department of Justice agent Quentin Locke. He battles Q the Automaton, a metal “Frankenstein” that “possesses a human brain which has been transplanted into it and made to guide it” as a “conscienceless inhuman superman.” Actually, Q turns out to be a metal suit slightly clunkier than Iron Man’s original, and Houdini squanders his screen time writhing out of ropes and whatnot.

He also battled a band of Bedouins serving a “hellish ghoul-spirit of the elder Nile sorcery.” H.P. Lovecraft ghost-wrote the purportedly autobiographical sketch, but only after telling his Weird Tales editor that Houdini was a “bimbo” and a “boob.” (A friend of mine, poet-turned-horror-writer Scott Nicolay, mailed me a copy of “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” padlocked in a canvas bag that I still can’t get open.) Houdini’s other ghosts penned him a detective thriller, The Zanetti Mystery, the sleuthing spirit Daniel Stashower has been keeping alive in a series of Houdini novels, even pairing him with Sherlock Holmes in The Adventure of the Ectoplasmic Man.

Sherlock does not believe Houdini could walk through brick walls “by reducing his entire body to ectoplasm . . . the stuff of spirit emanations.” But Sherlock’s creator, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, did. “My dear chap,” he asked Houdini, “why go around the world seeking a demonstration of the occult when you are giving one all the time? My reason tells me that you have this wonderful power, for there is no alternative.” After his son’s death and his wife’s convenient discovery of medium skills, the evangelical Doyle toured the globe giving lectures for the Spiritualist cause. He and Houdini were both psychical investigators and so instant frenemies, each casting the other as his Moriarty. Like Professor X and Magneto, Doyle tried to persuade Houdini to use his powers for good: “Such a gift is not given to one in a hundred million, that he should amuse the multitude or amass a fortune.”

Houdini listened. He dedicated his brain and gifts to fighting Doyle’s ghoul-spirit religion. He kept X-Files full of criminal mediums and employed a band of undercover operatives, his “own secret service department,” to infiltrate congregations across the U.S. He proved himself a master-of-disguise, donning wigs and beards and plaster noses to sneak into séances and expose fakes swindling the bereaved. Like Batman, the memory of his mother drove him, that and the certainty that if the dead could communicate to the living, surely she would have reached her doting son in at least one of his endless attempts. Houdini’s wife took up a similar cause after his death.

When I saw Metamorphosis performed, the magician invited an audience member onto stage to inspect the crate and cuffs. A seventeen-year-old Walter Gibson had that privilege in 1915. He became one of Houdini’s ghost-writers, succeeding him as president of the Society of American Magicians. He waited four years before publishing Houdini’s Escapes and Magic. CBS’s Detective Story Hour premiered in 1930 too. The radio show featured an omniscient narrator with a demonic laugh and knowledge of the hearts of men. When listeners couldn’t find the character on newsstands, the publishers phoned Gibson, and he wrote the premiere novella for The Shadow Magazine, the first of 282 he would pen.

In The Ghost Makers, the Shadow battles phony spiritualists, but when CBS hired Orson Welles to star in a 1937 radio reboot, Gibson dumped the band of operatives and sent his master-of-disguise “to India, to Egypt, to China . . . to learn the old mysteries that modern science has not yet rediscovered, the natural magic . . .”

My sister was on stage during the whole performance. She was one of those dancing distractions Houdini used too. The cuffs were fake, the sack opened at the bottom, and the crate lid pivoted on a hidden hinge. But everything else was real.

More on The Grim Game and the up to date inside secrets and details of how it was found and restored with the help of Turner Classic Movies, Dorothy Dietrich and Dick Brookz go to,

Here is the link

http://houdini.org/houdinigrimgameuncoveredbyhoudinimuseum.html

Impressive research, Chris! Enough unlikely and significant connections for a gothic novel…