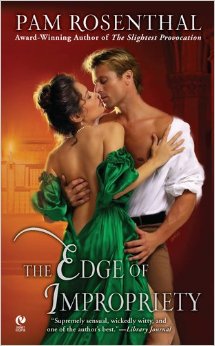

At the end of Pam Rosenthal’s 2008 regency romance novel The Edge of Impropriety, we learn offhand that Lady Isobel Wyatt and Miss Amory, two wealthy young women who had been seeking husbands during the season, have “determined to live together as companions and had set themselves up in a Welsh cottage.” The information is about minor characters, and is dropped casually — too casually, in fact. Rosenthal is telling us that Wyatt and Amory are lesbians, and in doing so, she rewrites, or reinterprets, every scene in which the characters appeared. When Miss Amory, the American heiress, watched eligible bachelor Anthony courting Wyatt, she was jealous — but the jealousy, we now realize, was because she was in love with Wyatt, not with Anthony. When we overhear Wyatt telling Amory that she has turned down Anthony’s proposal and is truly happy for the first time in her life, that happiness, on rereading, is not just because of a loveless marriage avoided — it’s because of a loving companionship embraced. Wyatt and Amory are treated throughout the novel as a kind of side plot; they are edges of Anthony’s love triangle. But then, at the end, we find that triangle was concealing another, and that the two women have their own hidden story, if you know how to look for it.

At the end of Pam Rosenthal’s 2008 regency romance novel The Edge of Impropriety, we learn offhand that Lady Isobel Wyatt and Miss Amory, two wealthy young women who had been seeking husbands during the season, have “determined to live together as companions and had set themselves up in a Welsh cottage.” The information is about minor characters, and is dropped casually — too casually, in fact. Rosenthal is telling us that Wyatt and Amory are lesbians, and in doing so, she rewrites, or reinterprets, every scene in which the characters appeared. When Miss Amory, the American heiress, watched eligible bachelor Anthony courting Wyatt, she was jealous — but the jealousy, we now realize, was because she was in love with Wyatt, not with Anthony. When we overhear Wyatt telling Amory that she has turned down Anthony’s proposal and is truly happy for the first time in her life, that happiness, on rereading, is not just because of a loveless marriage avoided — it’s because of a loving companionship embraced. Wyatt and Amory are treated throughout the novel as a kind of side plot; they are edges of Anthony’s love triangle. But then, at the end, we find that triangle was concealing another, and that the two women have their own hidden story, if you know how to look for it.

If Wyatt and Amory’s love is in a closet, though, it’s a closet within a closet. Because their Welsh cottage is not just their Welsh cottage, but the Welsh cottage of everyone in the novel. In The Edge of Impropriety, everyone, it seems, has a secret love, and, for that matter, a secret life. Lady Gorham, or Marina, the fabulous author and socialite, was once a poor Irish kept woman, forced to dance on tabletops for her upkeep. Helen, the perfect governess, is in love with the rakish, inaccessible Anthony. Jaspar, Anthony’s uncle and guardian, is actually Anthony’s father — and on top of that he’s concealing an affair with Marina. “Marina’s besotted lover and Sydney’s quaint, straitlaced guardian might inhabit the same body,” Jaspar muses, but they had very little to say to each other.” Everyone has a double life; everyone is playing his or herself for others, hiding a desire that dare not speak its name.

The key that opens the closets of that Welsh cottage, then, is also a key to the novel as a whole — which is to say, the novel is, in many ways, a closet. Wyatt and Amory are minor characters, perhaps, but Rosenthal’s emphasis on secret loves and secret lives makes them thematically central. To drive the point home, Rosenthal includes a scene lifted from (and directly referencing) the famous Catherine de Bourgh encounter in Pride and Prejudice, in which Elizabeth realizes that Darcy loves her because his aunt tries to separate them. Romance is interpreted by hints and signs — and not just by hints and signs, but by hints and signs between two women, whether Elizabeth and Catherine, or Marina and Jaspar’s ward Sydney, or the (generally female) reader and that some female protagonist. Romance is a book you read for hidden, queer love — which means those two women, and their Welsh cottage, aren’t a marginal storyline, but the story itself.

This isn’t just true for romance, either. Take the hip sci-fi Canadian televison thriller Orphan Black, which I’ve just gleefully begun to binge watch. The series focuses on Sarah Manning (Tatiana Maslany), a struggling young woman who discovers that she’s one of a number of clones. She ends up impersonating one of her “sisters”, a police officer named Beth .

Sarah’s brother, and closest friend is Felix (Jordan Gavaris). Felix is flamboyantly gay — and the fact that he is so far out of the closet tends to force you to read Sarah as in. Sarah, after all, is, like the characters in The Edge of Impropriety, playing herself. She takes on Beth’s middle-class, straight life — wearing her square clothes, living in her square house, and (with a notable lack of enthusiasm, at least at first) having sex with her square boyfriend. In one sequence, Felix is asked over to a suburban potluck as a bartender in order to distract from the fact that clone Allison has her husband tied up in the basement for questioning because she thinks he’s a spy. Felix, out of the closet, is a screen for Allison’s kinky torture role-play — a doubled roleplay, since for part of the torture, Sarah is pretending to be Allison.

As the show goes on, Sarah’s square boyfriend turns out not to be what he appears either, which only perhaps underlines the point. Spy narratives are built on secrets and double lives, on passing for what you aren’t while keeping some sexy secret gun behind that secret closet door. It’s no surprise that one of Sarah’s clones turns out to be bisexual, since Sarah herself spends all her time passing. And for that matter, all those sci-fi clone and robot fictions, are about queer reproduction — a world in which heterosexual sex is displaced by alternate couplings.

The Edge of Impropriety and Orphan Black both reflect a world in which LGBT people are more accepted, and more visible, than in the past. But that has not banished the LGBT experience as a fictional metaphor or trope. Rather, it seems to allow us to see just how pervasive, and important LGBT stories have been to the construction of narrative and genre. Critics of diversity sometimes argue that advocates are pushing gay content — but these stories suggest that in romance, in sci-fi, in espionage, gay content was always already there to begin with. It’s just that now, and hopefuly increasingly, it can come out of the closet.

Hmm. I didn’t think of it that way when I wrote it, but in fact the next big theory glom I went on was Eve Sedgwick’s work on queer theory, including THE AESTHETICS OF THE CLOSET. So who knows?

I think you mean the Epistemology of the Closet? Unless she has another one I don’t know about, which is possible?

Do you mean you didn’t think of Wyatt and Amory as gay? I am taken aback if so — they’re obviously gay! Maybe they were just being discreet…?

I fondly remember your talking about Sedgwick and romance at the 2010 IASPR conference, Pam, and I wouldn’t be surprised at all if comparable ideas weren’t on your mind much earlier.

Noah, my favorite bit of pop culture’s gay content hiding in plain sight is Etta James’s “All I Could Do Was Cry.” The first verse tells a lesbian story, and then the chorus hustles in to change it to a het one. (First verse: “I heard church bells ringing / I heard a choir singing / I saw my love walk down the aisle / On her finger he placed a ring.”)

Duh. Epistemology. Of course. No, of course they’re gay. But I didn’t think of their closet as the book’s thematic center. Just an added pleasure, a sense that pleasure radiates further than you think, out from the expected center. I think romance is very often about secrets, and so are large swathes of narrative. Sedgwick would probably say that that’s the queerness at romance and narrative’s center. Maybe.

Actually, it used to be very common for women to set up house together, whether straight or gay. Women living alone were rather frowned on.

Sorry if this one will be a duplicate; it hasn’t “taken” yet.

Alex, you’re right about women living together, but my Edith and Isobel are definitely lesbians, and a clear reference to the then-famous very probably lesbian Ladies of Llangollen, who set up housekeeping in Wales http://historyhoydens.blogspot.com/2007/03/time-well-spent-ladies-of-llangollen.html

Pam, oh good; I didn’t think I could be reading that in!

There’s a lot about secrets and such in the book — everybody’s love is in the closet, everybody’s living a double life. Or at least that’s what struck me on reading it….

Alex, Sharon Marcus’ “Between Women” puts this in the context of same sex friendships, erotic and otherwise, during the Victorian period. Basically, at the time, there wasn’t much concept of lesbian identity, but that meant that erotic desire between women was viewed as normal for heterosexual women.

Marvelous book, “Between Women.” So glad you mentioned it. I am a huge Sharon Marcus fangirl. I believe her next project is Oscar Wilde. But you know, the originals of my Edith and Isobel was the then-famous “Ladies of Llangollen,” who lived together in Wales, dressed in their own gender-neutral style, and received the literati of the early 19th century. No one can know about the sexual details of their life, but reading their diaries, it’s hard not to believe they weren’t lovers as well as each other’s “beloveds.” I blogged about them years ago.

The American version of same-sex cohabiting woman couples was called a “Boston Wedding”.

Sharon Marcus has written for this blog! I just met her in person; she had me come to New York to talk about Wonder Woman. Her next project is on pre-20th century celebrity; she did a Q&A about it on Reddit recently….

“. Felix is flamboyantly gay — and the fact that he is so far out of the closet tends to force you to read Sarah as in.”

What does “gay” mean in this context? If you’re using the word to mean “homosexual” you’re really not saying things that have much to do with the actual story, where Sarah is never depicted as attracted to women and Allison’s torture scene is with a man she met in college and married. (And she’s not engaged in kinky role play, she’s really trying to torture him).

Your broader point seems to be that all spy shows are gay (whatever you mean by “gay” I have no idea). If you really mean homosexual- you’re kind of more freudian than freud. A cigar is always a penis, spy shows are always gay.

I mean- Orphan Black has something like three or four gay or bisexual characters- but you seem to want to say by process of being on screen with them all 20 characters are gay. It seems kind of hyperbolic to me.

Felix the character is gay. He’s homosexual.

I talk pretty directly about how spy stories function in terms of the closet here. It’s kind of more text than subtext. Sarah at one point actually pretends to be her clone, sharing a kiss with her girlfriend. Similarly…you realize that the show isn’t real, right? So the kinky role-play scene is actually, really, in real life, a kinky role-play scene. I’m giving the surface, real-life reading; you’re reading into it to get fiction.

But…as I try to say here, all these moves of doubt and knowledge; the insistence that you can’t know, or that you’re debased if you do know — that’s all functions of the closet, too. Codes and truths around what can be and can’t be known, about what’s allowed to be a secret and what isn’t — that’s all interpreted through the closet. Eve Sedgwick argues that the closet, and gay experience, are constitutive of narrative, and she makes a good case for it.

Well I haven’t read any “queer theory” but I noticed the article was titled “The Romance of the Closet” but you were talking at one point about a heterosexual kinky scene between Allison (or Sarah) and her husband- so what came to mind is, what does the term “gay” or “in the closet” mean in this context?

I’d say Orphan Black is a show about identity. Sexual attraction is only one aspect of identity.

The show really isn’t about being gay and being in the closet, it’s about “identity” and concealing and revealing and defining identity in context of other human beings and society.

I think it makes more sense to interpret some of the clones as straight and other as gay, because they have different identities. They are sort of a range of human possibilities.

Or maybe the gay vs straight paradigm doesn’t make any sense in Orphan Black to begin with… if the clones represent all humans, their sexuality is like a superposition… all things to all people.

So, BDSM and other alternate sexualities are often included with LGBT identities as part of queerness. Sexual identities that you hide; that’s the closet. It’s about queerness. So, yes, bondage play in your basement while your friends mill about upstairs has everything to do with the closet.

You’re assuming that “all identities” is broader than “queer identities.” That is, the center is the center, the margins aare marginal glosses on that center. One of the insights of queer theory (and of poststructuralism more generally) is that that seemingly common sense position is naive, or at least often insufficient. Margins define the center, not the other way around. So, in order to make all lives matter, you need to say #blacklivesmatter; the hashtag about black lives is actually more inclusive than one which said #alllivesmatter. Similarly, you say, “Orphan Black is about all identities” — but the way it structures an understanding of all identities is through fairly obsessive referencing of the closet and queer identity.

I don’t think the clones represent all people, either — or at least that seems reductive. I hope to write a post at some point about how the show seems particularly to be talking about female identity (it’s obsessed with reproduction, among other things.)

I’ve read an article saying that Orphan Black was about the objectification of women (the clones are treated as intellectual property). That seemed plausible enough- so I wouldn’t object to a reading of the show as being about female identity- however that article came out after season 2 and your not caught up yet so I won’t go into details about the argument so as to not spoil anything for you.

I’m into season 2 now…and I don’t really care about spoilers. The intellectual property seems like an interesting reading. I think the show also makes a pretty clear case that biology is not determinative (which is a fairly baseline argument for a lot of feminists.) I’ve got some other ideas as well…

Well basically at the end of season 2 the cliffhanger is a male clone line exists, so the argument in the article I read went that the show had been about the objectification of women but season 3 will likely be about the objectification of men- and the male clones seem to be connected to the military- so they presumably are treated as cannon fodder “drafted” into service.

So if the writers are smart about season 3- we might have a theme of female experiences of society threatening personal autonomy (literally related to reproduction issues, as you said) versus male experiences of society threatening personal autonomy and identity- (perhaps dealing with people drafted or coerced into the military) playing out in different gender specific ways.

So yeah you’re right that the Sarah clones in that reading don’t represent all humans.

Ah, that sounds fun. And good to know!