Editor’s Note: Nate Atkinson left this comment on my recent post, and I thought I’d highlight it here. It’s part of our recent discussion on Censure and Censorship in comics.

_________

Freedom of speech arguments suffer from the fact that the word “freedom” has become a God-term in US liberal-democratic discourse. In fact, what a lot of commenters are calling a value of the left is actually a value of classical liberalism, where “freedom-to” trumps “freedom-from.” This isn’t an accident, as liberalism views that the individual is the fundamental unit of society, and thus views anything that restricts those freedoms as a threat to the social order. Compare this to a society that defines freedom as “freedom-from,” as in freedom from want, or freedom from threat. In those societies, a person’s freedom-to is more readily limited to assure freedom from (that’s where we get truly progressive taxation). Importantly, both definitions of freedom allow for democracy, though freedom-to is more encouraging of laissez faire capitalism.

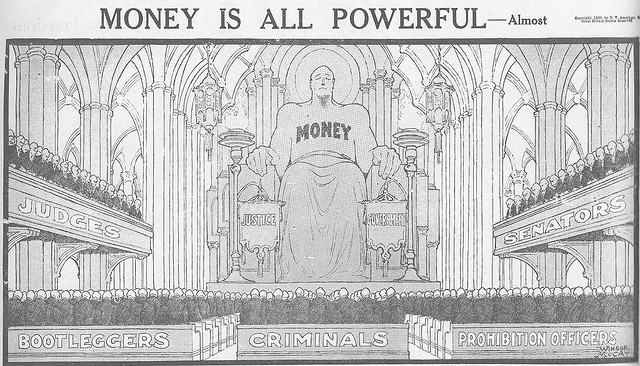

So what does this have to do with speech? The smart-ass answer is that in a country where money=speech, the emphasis on freedom-to provides an argument for unlimited campaign donations. But that’s not what we’re discussing here, is it?

When we talk about freedom of speech we default to the “freedom to speak.” We forget that when we protect the freedom to speak we risk impinging not only on freedom-from speech, which is to say freedom from speech that makes the world a difficult place in which to live, and for certain people, to speak. Paradoxically, the unreflective privileging of the freedom to speak actually creates an obstacle to freedom of speech. And this gets me to the question of moral goods.

As a society, the US has a long history of divorcing politics from questions of moral good. There’s a reason for this, which is that the pragmatism of Rawls (and to a lesser extent Dewey) greases the wheels of discourse by bracketing questions about what is “true” or “good” and focussing instead on questions about what is legitimate and procedures for securing a consensus. As a result, assumptions about moral goods sneak in through the backdoor and elude sustained examination. Everyone just agrees that freedom is good without actually examining what freedom means, not only to them, but to others. Freedom-to is conflated with freedom-from, and we all truck along under a false consensus about what freedom of speech means.

However, if we unpack the notion of freedom even a little, we see the dynamic between freedom-to-speak and freedom-from-speech. This creates dissensus, which makes it anathema to pragmatism, but it also allows us to recuperate freedom of speech as a moral good, something to nurture and protect. This would allow us to discuss it as more than means to an end, a means that might or might not outlive its usefulness.

by Winsor McCary

I should add that I’m painting in really broad strokes here… As I mention in a follow up comment, freedom-from can be read as freedom from government interference, which actually plays quite well with libertarian philosophies. Nevertheless, I stand by my comment and I’m flattered that Noah gave it platform.

i greatly appreciate Nate’s insight. I still feel like slavery is pretty important to consider in contradistinction- freedom is only a concept (like all concepts) that is meaningful if it can be opposed to something, and I doubt anyone was talking about freedom before the existence of slavery (which is not a recent invention).

Freedom “from” slavery is, then, a much more succinct phrase than freedom “to” not be enslaved. But I kind of feel as if “Freedom from slavery” is the only “freedom from” that means anything. Of course societies should protect vulnerable people, but to call that protection “freedom” seems like a problem with the use of the word “freedom” as a catch-all for political ideals.

I think your reasoning works only if we suppose a binary model of agency, as in you have it or you don’t, and once you have agency all freedom is positive. The problem is that some people are more free than others in most societies, which is why I maintain that freedom from is a useful concept.

The Romans referred to “liberation” as an attribute of citizens that just meant “not enslaved.” I think talking about a spectrum of oppression is all well and good. But the reference point of slavery is still what gives “freedom” (as opposed to “rights,””autonomy,” what have you) any specific meaning. “Freedom from” is a rhetorical move, and it has some appeal, but I think it ultimately rings awkward.

“Liberatio” rather. Stupid autocorrect.

I think you’re right that in the western tradition, of which Rome is a big part, freedom is generally thought of in terms of the Roman conception of liberty. That we’ve modeled this notion after the logic of a slave state is actually a big problem, and you don’t need to be a radical critic of the Enlightenment to see why this would be the case.

That freedom from “rings awkward” speaks to the degree that in a liberal democracy, (that is to say a democracy based on Enlightenment ideas about the relationship between the individual and state), has become a cultural given, or norm. These sorts of norms work well enough until there’s a controversy, at which point the unexamined premises behind the norm come to the foreground. This is, I think, what often happens in arguments about freedom of speech. We begin from the premise that freedom of speech is something we have or we don’t. This prevents us from seeing how the freedom to speak might impinge on others’ freedom from speech (speech that degrades, speech that overwhelms), which in turn impinges on their freedom to speak (self-censorship). I’ve hesitated to use the term, but we’re looking at a dialectic here, and I think we’re doing ourselves a disservice when we accept social norms as rules for discourse.

Also, I’d be pretty suspicious of any rhetoric that reduced the to/from relationship to one half of the binary for political gain. As I said, I don’t think you can have one without the other, and I think the character of both are historically and contextually bound.

It’s just that making “freedom” do all the work in regard to speech doesn’t question the word as the unsurpassable ideal of American civilization. In the “liberty, fraternity, equality” triad, maybe “fraternity,” date rape connotations aside, should be doing that work. I don’t know, it’s all semantics- thanks for engaging on this.