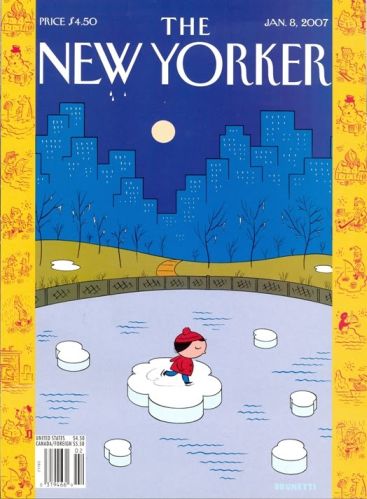

Is that a girl or a boy skating there?

Ken Parille, in a recent analysis of this Ivan Brunetti cover at tcj.com argues that it’s a girl, and, partially on the strength of that gendering, places the cover in a tradition of sentimental art.

With eyes closed, her face wears a contented expression. While traditional sentimentality sees a woman’s value as defined by her relationship to others (as wife, mother, daughter, etc.), Brunetti’s cover celebrates female solitude and introspection — a romance with the self.

When I initially saw the cover, though, I saw the figure as a boy — and the gender switch arguably changes the genre. As Parille notes, the person here may be engaged in contemplation, but she (or he) also seems to be violating the rules; he’s jumped the fence and is now skating on a chunk of ice where there’s some danger he’ll fall in. Seeing her as a her, Parille ends up underlining the ominous threat; “Her rebellious actions are admirable, even inspirational, but a little reckless. Perhaps she should open her eyes.” But is she’s a he, you might switch that about — it seems a little reckless, but even so, inspirational and admirable. She isn’t a girl in need of saving; he’s Tom Sawyer on an escapade. The figure isolated against the city isn’t inward turned and contemplative, but serenely pleased with his daring. The New Yorker readers get to identify with that lone figure, impishly crossing boundaries and frolicking where one should not frolic. The three drops falling from the title, which Parille reads as tears, might perhaps be seen as bright stars, confetti — a small tribute to the daring youth, and the viewer who dares with him (at least intellectually, in the way of New Yorker readers.)

Parille is probably right about the gender, as far as the artist’s intentionality goes (I get the sense that he’s probably spoken to Brunetti about it.) But of course no one can be right about the gender in an absolute sense; images don’t have gender really; a drawing has no genitals; even if you draw genitals, they’re just lines on paper. The gender is a convention, and part of that convention is genre — in the sense that the genre you see has gendered implications, and vice versa.

Though at the same time, I do wonder — are the genres all that different? Girls’ sentiment and boy’s adventure seem less like opposites, here, and more like a different way of looking at the same image; a gestalt shift. Is he mildly mournful beneath a sorrowful moon? Is she impishly pleased with herself under cover of darkness? Will they fall into their lovers’ arms, or answer the Bat signal? Which melodrama do you choose? Or will you stay, poised and refined above it all, avoiding those damply gauche pulp pleasures by skating upon a thin surface of ambiguity? Male or female, our iconic representative floats upon self-conscious, ostentatious whimsy, the genre of genius.

Or perhaps, in its sadness or sentimentality, it’s a take on global warming — a spin on the castaway polar bear, or a last nighttime refuge from the oncoming sun. The title is not crying; it’s melting. This may be the last skate, ever.

And this is more than just a guess: I’m pretty sure every one of the images on the sides of the cover — melting igloos; sun-stroked penguins; Santa in the rain — bears me out.

Ken mentions the global warming possibility. I don’t think that makes it unsentimental, though. Last skate before the world ends is not an unsentimental theme.

I see it! S/he’s skating on a tiny piece of ice! How delightfully absurd! Tee hee!

The word I failed to use is “twee.”

The more I look at it, the more I hate it. I guess it’s stupid to be pissed at the New Yorker for being smug and self-satisfied. It’s like being upset at McDonald’s for selling crappy food. The business plan is the business plan.

I think the global warming references actually work both ways too, fwiw. Elegaic, world ending or impish defiance in the face of the deluge are both possible (and probably intended) readings.