This is part of a Blog Carnival organized by Women Write About Comics.The entire round table on Censure vs. Censor is here

__________

Cold open on the Oxford English Dictionary: two words that kinda sorta look alike. Part of me wants to drop them at the top like a 10th-grade English essay. I could ask a whole high school to write about the difference between censor and censure and see nothing half so stupid as the conflation of the two we see in comics discourse today. You’d think the solution would be so simple as to point out the mistake—to say this isn’t that. What I’ve come to understand over the last year or so is that trying to talk to people about freedom of speech in comics is like trying to reason with your drunk uncle about racism: appeals to logic simply aren’t going to work.

‘I know what you’re thinking about,’ said Tweedledum: ‘but it isn’t so, nohow.’ ‘Contrariwise,’ continued Tweedledee, ‘if it was so, it might be; and if it were so, it would be; but as it isn’t it ain’t. That’s logic.’

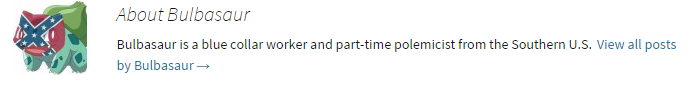

The last person here at HU who explicitly addressed the difference between censure and censorship was Jacob Canfield, who pointed to an inversion of logic: people defended Charlie Hebdo’s right to free speech by (falsely, absurdly) deriding its critics as proponents of censorship and even murder. The post went viral in mainstream media, garnering Jacob a lot of racist blowback—not just from people who disagreed with his ideas about racism, but also from racists who disapproved of him personally. One of the most amazing “critiques” he received along these lines was from a right-wing troll with a super silly avatar: a Bulbasaur with a Confederate flag superimposed on its face.

“The meat of the article was focused on the disgustingness of me as a not-quite-white-person,” Jacob wrote. “It was funny to read the stereotypical ‘get out of my country’ shit directed at me, coming from Confederate Bulbasaur.”

Man oh man. Months later, Confederate Bulbasaur is *still* cracking me up. Much like this guy I wrote about at Comics & Cola, he has made my Internet a happier place. Now all racist commenters, including outspoken atheist Patton Oswalt, are Confederate Bulbasaur to me. Jacob’s anecdote resonates because writing about racism and sexism on the Internet can be as funny and absurd as it is depressing. Confederate Bulbasaur is emblematic of the particular maddening and comical experience that is writing about those issues in comics. A rich symbol, he also represents futility. There’s really no use in arguing with a guy like that; if he can’t see what makes him ridiculous, there’s no way that anyone is going to be able to explain it to him.

In lieu of definitions, let me tell you something that might not be immediately obvious given how many people keep quacking about it: Censorship in American comics is a dead moral question. Yes, yes, I know CBLDF is out there fighting the good fight against conservatives who want to ban books from libraries and so forth, and kudos to them for that important work. I’m not talking about anything that involves the actual law. I’m talking about the fact that no one speaking from within comics today is a proponent of censorship, de facto or otherwise; it is unanimously decried by all of us. The pro-censorship side of the argument simply does not exist.

And yet, censorship is an accusation frequently hurled at “politically correct” liberal-leaning members of the comics community. The accusers are, like, Tinfoil Hat Bulbasaur, sometimes even using words like self-censorship and thought police to describe what most of us would call a conscience. We’re through the looking glass, where the people with the most power and the loudest voices are the ones who worry most about being silenced. Potent industry figures like Gary Groth are waging an imaginary war against opponents (“opponents”) who have no actual interest in stripping artists of their freedom of speech. So let me say it once, loud and clear for all the turkeys in the back: Expressing an opinion—even a harsh one—is not equivalent to arguing for censorship. It’s not even close.

So why does a dead moral question carry so much weight in comics discourse today? First and foremost, cries of “Censorship!” are an effective way to quell uncomfortable conversations about sexist racist garbage comics. (Anti-censorship is an easy position to defend because it doesn’t need defending; everyone already agrees with it. If someone were to explicitly defend bigotry, well, that’s a tougher sell.) This agenda dovetails nicely with the values of people for whom the most real and salient moment in comics history is not now, but decades ago, in the underground’s resistance to the Comics Code Authority. And finally there’s the lived experience of older white men (and, occasionally, older white women), who are so accustomed to speaking freely, and so unaccustomed to having people challenge their views, that they’re fundamentally incapable of understanding the difference between being forcibly silenced and being called an asshole.

Here at HU, I sometimes write about people when they act like assholes, not out of personal animosity, or even hope that I’ll change their minds, but because the live issues I perceive in comics discourse pertain to forms of silence other than censorship. Some are borne of power differentials I can name, like the phenomenon of punching down, or refusing to listen. Some stem from cowardice, like the unnatural quiet that descends across prominent platforms when someone important behaves badly. Many others are more difficult to articulate. How can I effectively describe the silence of someone who’s been rendered mute by anger or frustration? Or the silence of people who are just too tired of this stuff to bother speaking up? What is the word for the kind of silence that comes from disgust, or out of the fear of being treated poorly?

By definition, silence is not something I can present to you as evidence, but these people are not hypothetical; they’re real, and they are effectively rendered invisible. Their voices are profound in their lack. Some are lost and some are lurking and some are just plain gone. Some never even existed, quelled before they could be found. Some are mermaids, singing each to each in the vast and mysterious ocean that is Tumblr. Obviously I can’t speak on behalf of these missing persons. I find it hard to even speak about them since they’re so abstract. Instead I focus on my anger, which is huge, and the comedy of it all, which is not inconsiderable. I write about the voices I hear and the things I see, and I’m blown away by how much of it is total fucking nonsense.

Censorship, though—for this we have a word with a meaning. Look it up and write it in your notebooks, friends, because its constant misuse has real-world ramifications. From comics to comedy to videogames, people who invoke this dead moral question to demonize political correctness are either straight-up stupid, or acting in service of something else (usually nostalgia, fandom, white male supremacy, or some combination thereof). No one in American comics today—no creator, no fan, no publisher, no marketer, or critic—is actually arguing about censorship. The next time you see someone sling that word around, ask yourself what, in fact, he or she is fighting for.

“I’m talking about the fact that no one speaking from within comics today is a proponent of censorship”

Actually, virtually everyone in comics is in some ways pro-censorship. When there was a debate over the Milo Manara Spider-girl cover, I don’t think anyone was suggesting he should be able to publish it without Marvel’s permission.

The idea that copyright laws should censor the expression of comic creators is accepted by virtually everyone.

I guess I’d say censorship is institutionalized to such an extent that it appears invisible, and the issue of “censorship” is only brought up by people who have other agendas.

As far as mainstream comics goes, the issue (as with the Batgirl cover) is almost always about whether something should be “official.” “Censorship” of the Batgirl cover was about whether it could be a “real” cover, i.e., appear on the actual Batgirl comic. No one was suggesting the image be scrubbed from the Internet, where it was in fact widely available and viewable by the people who were claiming it was being censored.

Not free speech, but corporate imprimatur, is the bone of contention.

It’s true that Marvel and DC tend to turn a blind eye to one off unauthorized drawings of their characters on the Internet- and not for profit obscure fanfic type works. But the corporate imprimatur is a concept that derives its moral authority from the government censorship regime- Milo Minara isn’t going to self publish a long form Spider- woman comic because it would be illegal.

We’re not just talking about a situation where fans would label him a heretic- lawyers could sue him for violating copyright if his version of Spider-girl was seen as a threat to Marvel’s. So any commercial artist is going to – to some extent – voluntarily comply with the censorship laws

Also it’s too simplistic to say its just about the Batgirl cover and whether it was official. It’s also about whether DC allows artists in the future to do covers of that nature. And DC artists are always censored by the intellectual property laws, they can’t just draw whatever they want without DC’s permission- at least if they want to earn a living and be risk free from litigation.

Yes, but the Batgirl example is complicated by the fact that the artist himself requested its withdrawal.

And that terrible Canfield post is really indefensible. At one point he out-and-out deceives by his mistranslation of the Boko Haram cover.

Interesting to note that Canfield doesn’t consider Arabs to be White people.

Alex, I said we’re not going into this again. I’ve deleted my other post as well, since that seems to have opened the gates. If people want to talk more about CH, we’ve got a ton of posts with open comments threads. We won’t be going into it again here.

The creative team on Batgirl also didn’t want that cover.I don’t think it’s really an issue of “will DC ever again be able to portray violence on a cover.” Much more about which covers particular fans of particular comics want to see.

Pingback: Censure vs. Censor: A Blog Carnival

The issue of censorship is definitely overblown when it comes to comics (and a lot of things on the internet), and as Kim rightly points out is mostly used as a deflection or distraction.

What is of more interest to me, however, is not so much direct censorship, but how talk is so cheap – so widely available, and most of it uninformed, unclear or unintelligent that voices like the ones here, or on my blog or anywhere can effectively disappear. Anyone can say basically anything they want because in the cacophony of bullshit none of it has any power to really change anything. Write me a comic that can actually get people listening and threaten to overthrow the government and you be writing me comic that gets censored.

I don’t know that I exactly agree that HU’s irrelevance is a kind of censorship….

I do think there are situations which effectively lead to censorship. Organized bullying online designed to silence people functions as censorship often, it seems like. In a lot of comments sections, abusive people can de facto drive everyone else away because it just isn’t worth dealing with the bad actors. And so forth; there’s lots of ways to push people out of the public square.

The point of the post is about formal censorship though, isn’t it? It seemed to me Kim was pretty clear that there are other ways to effectively silence people.

But the idea that formal censorship is a thing of the past struck me as over optimistic, although not being from the land of the free I could easily be wrong (globally speaking, you couldn’t seriously make that kind of claim)

Either way though, I don’t think Milo Manara’s right to self publish Spider-Woman comics really figures into a discussion about free speech…

I like this essay quite a lot, and I think Kim is absolutely correct that censorship is often invoked when people are censured for their B.S.

However, I also think that what these people are kicking at is not formal censorship on the order of the comics’ code, but the informal censorship that affects the silenced voices Kim describes, and what Noah called the “organized bullying online designed to silence people,” those “abusive people” who drive everyone away and “push people out of the public square.”

Of course, I realize that these cries of censorship are often (even usually) overblown, especially when they’re voiced by those in a position of power, i.e., people who have had run of the public square for so long that they perceive anything that threatens their dominance as SJW bullying. Nevertheless, I think it’s important to recognize this kind of censorship as real, and perhaps even more pernicious than official censorship, as it tends to affect marginal voices more than those already holding the microphone.

Pingback: I Swear To Be Critical

Pingback: Censoring the World: The Fight to Protect the Innocence of Children