“But before I be a servant in White heaven, I will rule in a Black hell.” Killer Mike, “God in the Building”, I Pledge Allegiance to the Grind, Vol. II

Promotional poster for Belle, directed by Amma Asante

Early in Amma Asante’s socially conscious romance Belle (2013), audiences spy a British nobleman walk with purpose through a lower class section of an unnamed port city. Humid, overpopulated streets obstruct the uniformed Royal Navy Captain’s passage. The nobleman enters an attic dimly lit by a small window and sparse candles where a middle aged Black woman waits for him. Dressed in everyday homespun and a worn apron she stands alongside a quiet tan child with brilliant brown eyes. Prepared and dressed by the matronly woman, the silent girl holds a simple doll and stands impassive, unmoving, and observant; her simple hairpin struggles to contain an infinite cascade of light sienna locks. After the untimely death of her mother, the nobleman plans to whisk the little brown girl away to his family, to her birthright. To privilege. The nobleman kneels, and offers chocolate. Reluctantly, the girl accepts. The year is 1769.

“How lovely she is,” the nobleman exclaims softly. “Similar to her mother.”

It’s easy to regard the nobleman’s plan as obvious and uncontroversial given today’s standards. Leaving for the British West Indies on a navigational expedition, the Captain intends to leave the child in the care of his uncle, William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, and Lord Chief Justice of the British Empire. With family. However, late Eighteenth Century Great Britain revolves around its slave economy; colonial procurements replete with agricultural wealth, exotic goods and slave labor revolutionized British high society. Propriety, refinement, culture — these were the watchwords of an Enlightenment where civilized humans were encouraged to exert the “freedom to make public use of one’s reason in all matters”, according to Immanuel Kant [i]. Kant and his enlightened contemporaries judged persons of African descent incapable of higher order reasoning; animalistic Blacks offer stark counterpoint to virtuous White humanity. British nobles viewed Africans as subhuman beasts, unfit for culture, education, or reason. As slaves, Africans lacked any capacity for aesthetic sensibility, according to Enlightenment thinking. Slaves were property, and property does not think, feel, or reason. Given this, the nobleman’s request runs afoul of his homeland’s strict social order; a global empire that demanded unfree labor for economic stability could not conceptualize Black humanity. One locates diasporic Blackness during this period on balance sheets, cargo manifests, and maritime rapists’ salacious reports, not within British mansions’ gilded contours.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Charles Stanhope, third Earl of Harrington, and a Servant (1782),

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Lord and Lady Mansfield reservedly accept the little brown girl, Dido Elizabeth Belle Lindsay, into Kenwood House, a massive estate in Hampshire Village, London. Left alone soon after her arrival, Dido walks among Kenwood House’s massive portraits, and through her wary brown eyes viewers spy a visual synthesis of Enlightenment individualism and slavery apology. Painted by preeminent portraitist Sir Joshua Reynolds, a founder and inaugural president of the Royal Academy, exhibited at the Academy in 1783 as Portrait of a Nobleman,[ii] and housed today within the Paul Mellon Collection at the Yale Center for British Art, Charles Stanhope, third Earl of Harrington, and a Servant (1782) welcomes all to eighteenth century British machismo.

Stanhope, encased in unblemished armor, stands upon an active and sweltering Caribbean battlefield, sword in hand, both preternaturally calm and oddly petrified. An adoring brown youth holds Stanhope’s plumed helmet and gazes above, awestruck at his master’s magnificence. Reynolds paints Stanhope as desperate to impress all with martial skill earned in the slick red mud of the courageous and the damned but enhanced in an elite art studio; this oil-on-canvas press release asserts virility to contemporaries and whispers vulnerability to posterities. Stanhope, barely a man, plays at war. [iii] Below foreboding clouds Stanhope’s pale, effete visage peers above glistening golden armor; his pointed, boyish chin, hairless face, and perfect, Proactiv complexion force modern viewers to regard English nobility as special, refined, comfortable, free from want or struggle. Contrast this against the adolescent Servant shoved against Stanhope’s left, against guileless brown smiles trained by the lash, against another Marrakech rich in human capital but poor in civic defense, and Stanhope’s serenity approaches incredulity. Under Reynolds’ direction Stanhope does not stand with us, but above us; there’s no sweat upon his ghostly brow, no dirt under his manicured fingernails, no blood on his thin steel blade.

Bartholomew Dandridge, A Young Girl with a Dog and a Page. (1725)

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

One can easily imagine Reynolds’ conversation with Stanhope upon completion of this commissioned work; the abject flattery, the direct reassurances, the stroked ego, the payment for service rendered. With this portrait Reynolds both thunders Anglo-Saxon dominance and whispers sly rejection of that fantasy, a noble veteran revealed as farce without his helmet. Modern criticism of this object centers on the anonymous Black Servant whose illiberal assistance literally frames Stanhope’s polish. Similarly, in Belle, Dido’s inarticulate frustrations with her uncle’s desire for a commissioned portrait of herself and her cousin Elizabeth Murray is centered on her silent disapproval of the dark servant shadows who frame British portraits during this era, contrasting White civility with Black servitude. Paintings like Bartholomew Dandridge’s A Young Girl with a Dog and a Page (1725) and Arthur Devis’ John Orde, His Wife Anne, and His Eldest Son William (between 1754-1756) typify Enlightenment prejudice against Black personhood; baby-faced background slaves assist blanched central figures who thoroughly enrapture the pitiful anonymous with sophisticated British grandeur.

With dark, curly hair and infantile wonder, the Servant in Sir Joshua Reynolds’ Charles Stanhope, third Earl of Harrington, and a Servant anticipates every cute Black child ever seen in Western popular culture, from Keisha Knight Pulliam and Raven-Symoné on The Cosby Show to Noah Gray-Cabey on Heroes and Marsai Martin on Black-ish. Cherubic and brown, servile and friendly, these children of the darker nation deflect others’ revulsion toward their melanin with youthful gaiety and infectious innocence, and Reynolds co-opts this to both parallel the untested manhood on display and show Stanhope’s privileged freedom as natural and moral.

The peculiar institution’s American apologists often invoked the artless Sambo stereotype to justify their generational plunder of Black labor, wealth, and self-determination; it is easier to justify the transatlantic slave trade’s depraved criminality when we consider those reduced to beasts of burden emotionally underdeveloped and cognitively deficient.

“Comparing them by their faculties of memory, reason, and imagination, it appears to me, that in memory they are equal to the whites; in reason much inferior, as I think one could scarcely be found capable of tracing and comprehending the investigations of Euclid; and that in imagination they are dull, tasteless, and anomalous. But never yet could I find that a black had uttered a thought above the level of plain narration; never see even an elementary trait of painting or sculpture. … I advance it therefore as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.” — Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, Query XIV (1784)

Arthur Devis, John Orde, His Wife Anne, and His Eldest Son William. (between 1754 and 1756)

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Art historians speculate wildly about the Servant’s life, and the lives he represents. Whether colonial acquisition or indentured employee, the Servant signifies Great Britain’s longtime human trafficking and exploitation; modern viewers experience Stanhope as majestic, proud, and free, largely because history’s judgments identify the barbarous subjugation and domestic terrorism behind the Servant’s awestruck gaze. Mouth agape, eyes wide, the angelic brown face registers wonder at a life without whips and chains and commands and fear; a life lived free. Liberated. The Servant illustrates lifelong submission to chattel slavery; Reynolds’ otherwise unmoving portrait appropriates the systemic plunder of Black bodies and the bureaucratic corruption of Black labor to establish and augment Western global hegemony. White dominance. Notice the intricate detail attended this secondary, unnamed, background figure. Regard the Servant’s cowering awkwardness and unsure social position, both justified by the coerced assistance he renders. Compositionally, the patient attendant holds the viewer’s gaze and conscripts recognition of the static central figure. The Servant’s immaterial, indiscernible, questionable humanity fascinates, today more than yesteryear; because the Servant is inferior, Stanhope is superior. Because Blackness cannot equal freedom, Whiteness approximates divinity.

Sam Wilson and Steve Rogers. Man and Superman.

The intended narrative of Sir Joshua Reynolds’ Charles Stanhope, third Earl of Harrington, and a Servant operates as an eighteenth century White male power fantasy. Modern superhero comic media fans easily recognize this dynamic; mainstream superhero comic companies publish cartoonish variations on this worn, well-traveled groove ad nauseam to meet monthly operating expenses. Whether as friendly bystanders, costumed sidekicks, everyday henchmen or caped vigilantes, race and gender minorities exist in superhero comic media to validate and define the normative Whiteness central to the genre’s narratives.

Take Captain America: The Winter Soldier: early in the film we watch an athletic Black man sprint effortlessly around the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Wearing exercise shorts and a shapeless grey sweatshirt on a crisp spring day, viewers indulge athleticism, defined. Landscape shots capture republican majesty at the Washington Memorial and the U.S. Capitol. Suddenly a blurry blonde humanoid whizzes past, and frenetic limbs pump faster than the naked eye can detect. Comical frustration darkens Grey Sweatshirt’s expression: once, twice, thrice, the splendid blond beast laps the public track while Grey Sweatshirt bellows disbelief at his strained cardiovascular system’s futile effort. Played for laughs, this scene introduces viewers to Sam Wilson, the cheerful brother with an easy smile and Marvin Gaye on standby who extends friendship to a man living outside his era and outside his war, and who reminds viewers of the extra-normal abilities experimental industrial steroid injections granted this Greatest Generation throwback. “Blessed are the meek; for they shall inherit the Earth,” Jesus Christ teaches in Matthew 5:5; Marvel Studios’ Captain America: The First Avenger imagined that inheritance as tactical perfection augmented with avant-garde biochemistry and electroshock therapy. Doubtless, the screenwriters and producers of Captain America: The Winter Soldier applaud their intentional rejection of Black male stereotype, but to watch Steve Rogers literally run circles around Sam Wilson establishes a questionable on-screen dynamic that complicates this superheroic bromance at conception. In Captain America: The Winter Soldier, viewers experience the White protagonist’s superior physicality in contrast to a Black inferior, Charles Stanhope on creatine painted by Industrial Light and Magic. All this, to deify military service.

Captain America and the Falcon. Photo Credit: Zade Rosenthal ©Marvel 2014

Superhero comics employ violence to establish justice. To ensure domestic tranquility in Gotham or Hell’s Kitchen or Space Sector 2814 jackbooted vigilantes adorned in colorful, form-fitting leather and Kevlar ground and pound the criminally confused outside all legal authority. The superhero concept appeals to the adolescent desire to compel order through brute force, to define peace as the absence of credible threats. No matter how intellectually gifted or technologically adept or physically remarkable or preternaturally perceptive or unabashedly godlike, superheroes use violence to solve problems, foreign and domestic. The depictions of Charles Stanhope and Steve Rogers mentioned above show unsophisticated, immature White males who wrest manhood from their military experience, who telegraph masculinity by glorifying war. Yesterday’s crude colonial plantations and human trafficking syndicates drained profit from a world order enforced by eighteenth century British naval expenditures; today’s multinational technology conglomerates and global financial institutions wring fortunes from American guaranteed global stability. In this unipolar world, where the American hegemon assumes responsibility for political and economic stability from Minneapolis to Medina, from Seattle to Shenzhen, from Albuquerque to Addis Ababa, superhero action figures like Captain America argue the Athenian position in the Melian Dialogue; Rogers’ very existence symbolizes undisputed American technological supremacy. Of course, Rogers is not Cable, or Magog, or the Punisher, all logical extensions of the super-soldier concept updated for modern, antiheroic eras where callous scribes and tragedy pornographers painted scarlet horror in rectangular comic art panels while illiterate dealers and nihilistic gangsters sprayed arterial abyss on letterboxed nightly news broadcasts. Frozen in the cheery bombast of the last just war, Rogers’ outdated moral binary and Franklin Roosevelt phonetics convince comic fans that the extra-normal abilities he exploits service peace; given this conceit, we watch Rogers conscript Sam Wilson and Natasha Romanov into an ad-hoc terrorist conspiracy in Captain America: The Winter Soldier to incapacitate and scrap three floating, flying aircraft carriers authorized by American policymakers, funded by American taxpayers, staffed by untold hundreds, worth untold billions, because he alone determines the strategic advantage of perpetually aloft gunboat diplomacy counterproductive, an existential threat to world peace. The floating nuclear version at sea today does not enter the debate.

)Su•per•he•ro (soo’per hîr’o) n., pl. – roes. n., pl. – roes. A heroic character with a selfless, pro-social mission; with superpowers, extraordinary abilities, advanced technology, or highly developed physical, mental, or mystical skills; who has a superhero identity embodied in a codename and iconic costume, which typically express his biography, character, powers, or origin (transformation from ordinary person to superhero); and who is generically distinct, i.e. can be distinguished from characters of related genres (fantasy, science fiction, detective, etc.) by a preponderance of generic conventions. Often superheroes have dual identities, the ordinary one of which is usually a closely guarded secret. superheroic, adj. Also super hero, super-hero. — Peter Coogan, Superhero: The Secret Origin of a Genre, ©2006, pg. 30

Cyclops & Wolverine dismantle Sentinels. Comic unknown.

The superhero is a deceptively simple concept. The reactionary militarism, the thoughtless violence, the binary morality, the unquestioned righteousness, the colonial sociology — all of the superhero genre’s boyish charm reinforces the Western imperialist impulse to control, to order, to rule. The superhero genre does not promote fantastic Western imperialism alone: science fiction, espionage fiction, and medieval fantasy win popular culture’s hearts and minds with similar power fantasies designed for adolescent White straight males, sold globally. Still, every Wednesday, carrot-topped Caucasian perfection dons skintight primary colored lycra to unleash energetic ruby strobes at giant purple killing machines crafted in man’s image while a hairy Crossfit junkie with indestructible metal claws hacks and slashes fundamentalist cannon fodder amid blasé exurban spectators numb to repetitive superhuman brawls but unnerved all the same. Every Wednesday, superheroes seduce the innocent with disturbing commentaries on justifiable public conflict, acceptable casualty rates, and unspoken racial hierarchies. Superheroes are White male power fantasy distilled to narcotic purity, blue magic on white cardboard wrapped in clear polypropylene to show variant cover art. Consider Jim Lee as Frank Lucas.

Peter Coogan, founder and director of the Institute for Comics Studies, defines the superhero through a narrative triumvirate: selfless mission, amazing ability, and secret identity, all symbolized by a special moniker and distinct costume that elevates the new extra-normal persona to cultural iconography. The Batman’s elementary school ambition to channel elemental fear and unspeakable tragedy into a personal war on crime impacts everything about the character, from his costume’s shadowy color swatches, morose blue-grey later rendered midnight black, to his scalloped cape’s predatory motion silhouette, to his variable but always recognized centrally placed Bat-logo. Like Michael Jordan, we recognize Batman in profile with nothing more than dark cranial contours as evidence. Everything Bat-related identifies with a central simplicity: punish the bad man who killed Mommy and Daddy. †Law and order, uncomplicated.

“Despite what you may have heard, Superman is not a complicated character. He’s an extremely simple idea: A man with the power to do anything who always does the right thing. That’s it.” — Chris Sims, “Ask Chris #171: The Superman (Well, Supermen) of Marvel”, ComicsAlliance.com

This is the problem. For nearly eighty years, superhero comics etched the world in bright Crayolas, without emotional nuance or political complexity, to display imagined realms where the mundane and the fantastic coexist without incident. When the soapy X-Men adventure in the Savage Land’s meteorological impossibility, when the stately Justice League intercept planetary conquerors unfazed by Earth’s gravity or thermonuclear weapons, everyone drawn and colored and inked and lettered in panel conducts themselves in accordance or in conflict with mainstream, middle-class White American social ethics. The ‘right thing’ Chris Sims believes Superman insists upon remains a moral good defined in panel by rural Midwestern Protestants, and the superhero concept’s resultant normative Whiteness enjoys broad, international appeal. Most superhero comic fans regardless of race or creed or national origin judge Superman and his compatriots as truth and justice’s universal avatars, Golden Rule morality made myth. Because of this fantasy, fanboys and fangirls of color imagine themselves as living Kryptonian solar batteries who ignite still, unmoving skies with chaotic blue flame as they race through lower Earth atmosphere trailing angry pyrotechnics and leaking ozone while millions watch breathlessly, transfixed at an ungodly spectacle where petrified cosmonauts expect certain death after heat shield failure during reentry only to meet a scarlet and navy blue blur branded with hope’s own chevron in the upper stratosphere. The darker nation also wants to play the hero; they too, wish to be redeemed.

Make no mistake: this is a redemption song. The desire for full inclusion in superhero comics both behind the cowl and before the camera by patient progressive integrationists yearns to humanize those dismissed as unfit for heroism by superhero comics’ irrepressible identity indifference. Race, gender, sexual orientation: hashtag activists and comic bloggers clamor for more representation of all these political identities in superhero comics, television, and movies; whether straight-to-Blu-Ray animation or tentpole summer blockbuster, non-traditional superhero comic fans cajole, threaten, and shame mainstream superhero content creators into diversifying superhero and villain properties. Everything’s appropriate — racebending established heroes when franchises jump from print to live-action, with unconventional character origins that discard existing character history, cross-racially casting superhero protagonist roles, even cowl-rental, the shift of established major superhero properties from White male classics to new-age minority sidekicks — so long as nerds of color and their progeny revel in superheroes who approximate their phenotypes. I charge that this desire for inclusion — this need to see oneself in the corporate culture one consumes — is not ethical. When applied to the superhero concept, this inclusion is not possible.

Anti-busing rally at Thomas Park, South Boston, 1975 Copyright © Spencer Grant

Coogan’s definition is incomplete. To craft a superhero, add Whiteness to the mission-powers-identity troika; coat liquid latex and electrostrictive polymers onto the White body, code the costume design with identifiable brand marketing, apply catchy appellation. Done. Artistic license and open casting calls nurture false hope among nerds of color desperate for private sector social approval; these patient progressive integrationists forget that characters who wear their faces but forget their cultures do not promote their interests. These nerds of color also neglect history. Professor Derrick Bell, civil rights lawyer and intellectual progenitor of critical race theory in legal scholarship, wrote in the landmark “Serving Two Masters: Integration Ideals and Client Interests in School Desegregation Litigation” (Yale Law Journal, 1976) on the widening interest divergence between Black parents who sought high quality educational opportunities for their children, and the civil rights attorneys who fought to dismantle state-sponsored Jim Crow segregation with legal remedies applied to public education. For the lawyers, the grand revolutionary movement to desegregate American classrooms secured with Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, KS (No. 1.) the right to ensure “equal educational opportunity” in government funded public schools. Equal educational opportunity meant integrated schools, because for the lawyers only racial integration could guarantee Black children and White children received identical instruction. A generation after Brown, when public school districts needed forced busing to achieve numerical racial parity and angry middle and lower income White parents took to the streets to protest social experiments that designated their children test subjects, national civil rights attorneys from the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund held firm to the conviction that integration alone prophesied American race relation nirvana. This ignored, in Bell’s view, mounting social science evidence that chronicled forced busing-imposed student difficulties, class discrepancies in American integration experiences, and the ethical quandaries presented when civil rights attorneys routinely disregard or rebuff client perspectives.

An ahistorical pretense argues that integration presents the only salvation for an American experiment plagued in infancy by torture, rape, and genocide; chattel slavery and rampant land theft are not ‘birth-defects’, to paraphrase Condoleezza Rice, but cornerstones. From bondage on, Black political thought’s enduring fault line debates separation versus integration; from the titanic Frederick Douglass (“This Fourth of July is yours, not mine.”) through Booker T. Washington’s glad-handing industriousness and W.E.B. Du Bois’ pan-African intellectualism, through Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Birmingham fury at White liberalism and Malcolm X’s snide disdain for White patriotism, through the uneasy synthesis of partisanship and revolution from post-Civil Rights Movement Black elected officials and the criminalized irrelevance of Black Nationalist counterculturalists, the darker nation continually questions American citizenship’s lofty promises and David Simon realities. Casting integration as the sole pathway to postracial Eden in public education, superhero comics, or any other grand American tradition substitutes race visibility for race uplift, and confuses simple appearance with documented progress.

“To sum up this: theoretically, the Negro needs neither segregated schools nor mixed schools. What he needs is Education. What he must remember is that there is no magic, either in mixed schools or in segregated schools. A mixed school with poor and unsympathetic teachers, with hostile public opinion, and no teaching of truth concerning black folk, is bad. A segregated school with ignorant placeholders, inadequate equipment, poor salaries, and wretched housing, is equally bad.” — W.E.B. Du Bois, “Does the Negro Need Separate Schools?” The Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 4, No. 3, The Courts and the Negro Separate School. (July 1935), pp. 328-335

Fevered battles over forced busing ripped bare Northern antagonism toward civil rights advocacy; center-left White parents who nominally tolerated nonviolent civil rights activism responded to federal desegregation orders with the same massive resistance found below the Mason-Dixon. Casting the neighborhood elementary school as a ëWhite space‘ where John Q. Public easily sidesteps racial difference strikes cosmopolitan citizens today as antiquated, backward logic, like Salem’s witch trial groupthink or Cold War domino theory. Still, nerds of color walk behind enemy lines every Wednesday to stay abreast of Jonathan Hickman’s Avengers or Geoff Johns’ Justice League; for many the local comic book shop’s mainstream customer base mirrors the standard-issue suburbia within biweekly superhero stories. Progressive integrationist comic fans poorly navigate the irony around which Disney and Time Warner craft business models: regardless of race, gender, or sexual orientation, superhero comic fans wholly accept the antebellum identity politics of both the superhero concept and its target audience. Diversity does not sell superhero comics — nostalgia does, and this nostalgia hearkens back to postwar America, with its effervescent, bubbly nationalism, cleanly delineated racial hierarchies and obvious, unquestioned gender roles, even in private. For this reason, superheroes maintain their appeal to adolescent straight White males; everything in superhero narratives is designed to make Whiteness comfortable, to intensify the power of the privileged. Even nerds of color marvel when Captain America orders Sam Wilson to serve as his personal air support; computer generated scenes where Anthony Mackie’s sepia tones flit across Washington airspace spraying submachinegun rounds at unmasked Hydra agents while the winged brother evades rocket propelled death with hairpin banks at upchuck velocities satiate those who devolve superhero social justice into a Black actor’s screen time. Progress, for the superhero integrationist, requires nothing more than a regular census: survey the number of non-White, female, gay, lesbian, and transgender superheroes, and count the number of non-White, female, gay, lesbian, and transgender writers, artists, inkers, editors, and executives within the superhero comic industry. Tweet results with practiced outrage. Rinse and repeat. Qualitative analysis of minority portrayals violates the chirpy bluebird’s one-hundred forty character limit and does not engender comment.

Sam Wilson as The Falcon, played by Anthony Mackie, in

Captain America: The Winter Soldier

The only reputable progressive position on the superhero advises abandonment. The superhero concept’s narrow simplicity cannot possibly render human difference with substance or nuance. Corporate superhero fiction cannot dramatize the adrenal fear and visceral loathing police officers’ feel during traffic stops, sidewalk detentions, and no-knock warrants any more than it can judge the abject terror and furious anger the darker nation conveys through candlelight vigils, ‘I Can’t Breathe’ t-shirts, and Chris Rock’s unfunny selfies. “America begins in Black plunder and White democracy, two features that are not contradictory but complementary,” writes Ta-Nehisi Coates, senior editor of The Atlantic, in his landmark feature “The Case for Reparations“; in contrast, superhero comics lack all political theory more intricate than the Powell Doctrine. When Noah Berlatsky, writing at the Hooded Utilitarian on Static Shock, notes that the easy synergy between superheroes and law enforcement transforms Black superheroes into unwitting avatars for a modern mass incarceration state that translates public criminal justice into prison conglomerate profit, he should recall that urban post-Civil Rights Black elected officials championed draconian drug possession sentences with tough-on-crime rhetoric usually associated with Richard Nixon or Rudy Giuliani.

According to Yale Law School professor James Foreman, Jr., incarceration rates from majority Black cities “mirror the rates of other cities where African Americans have substantially less control over sentencing policy.” Black people, in the pulpit or the ballot box, can support robust and militaristic law enforcement initiatives deployed against their communities without tension, and those members of the darker nation with the financial stability and leisure time to engage electoral politics represent Black America’s most established, integrated, and conservative elements. What patience can veterans of color have with the dope pushers and domestic batterers and petty thieves and flamboyant pimps within their communities whose criminal enterprises depress already anemic property values? These old-school race men, with military precision and patriarchal inflexibility, assume the uplift of the race as personal responsibility; taught to kill by a country that hates them, taught to overcome prejudice with hard work and determination, the Black veterans who constitute the core of the Twentieth Century Black middle class personify bootstrap conservatism to chase economic inclusion, not revolutionary overthrow. This Black middle class, perennially called to account for a dysfunctional, systemically impoverished Black underclass left uneducated by dropout factory public education and unemployed by Silicon Valley’s outsourced manufacturing, loses its patience with both neighborhood criminals and municipal White political structures who concentrate drugs and violence and death in urban communities. Given this, Black elected officials these men chased the same militarized solutions to combat rising crime statistics during the 1970’s and 1980’s as their White counterparts, and municipal city councils stocked with pious Morehouse men and holy Spelman sisters proved no sturdy bulwark against dreaded million dollar blocks, no matter their local political success or state budget dependence. Unfortunately, when mostly non-Black superhero comic writers depict Black superheroes that support punitive carceral state solutions for minority criminality, no one references this history.

The problem here involves the superhero concept’s inability to envision non-White straight males as fully realized humans. The agony and the ecstasy of Black cultural and political complexity — from Jesse Jackson’s frustrated expletives in July 2008 over Barack Obama’s irrepressible moral centrism to Jesse Jackson’s joyous tears in November 2008 over Barack Obama’s irrepressible electoral victory — overloads the superhero’s straightforward make-believe. Black Panther, Black Lightning, Bishop, Mr. Terrific, Green Lantern, John Stewart, and U.S. War Machine: different power sets, different publishers, indistinguishable skin tones and identical personalities, all inflexible, assertive, upstanding old-school race men known more for quiet dignity than solo bombast, these characters present White male metahumanity shellacked with a moist black paste of burnt cork and water. I suggest that culturally authentic minority superheroes do not and cannot exist: all people of color receive from the superhero publishing industry replaces authentic and innovative characterization with race and gender drag. Sam Wilson’s instructive: these empowered Negro automatons unmask as superhero comics’ eternal sidekicks; they highlight White heroism’s astonishing brilliance and sacrifice race minority self-respect. This uncontroversial nostalgia justifies Black superhero inclusion in nearly every mainstream superhero team of note and illustrates an antiquated genre’s authorial recognition that the superhero concept cannot handle human difference. Every Black superhero is Will Smith drained of charisma, Denzel Washington without sex appeal, Barack Obama absent Michelle Robinson. All the same, all forgettable, all inhuman. Anonymous, nameless, Black. Other.

Michelle Rodriguez, captured by TMZ.com

When actress Michelle Rodriguez bellows “Stop stealing all the White people’s superheroes!” to a TMZ reporter, the initial backlash from superhero integrationists used digital condemnation and public shame to exact mob justice; within a day, Rodriguez’s pseudo-apology explained her disdain for superhero cross-racial casting as a desire to find multiple cultural mythologies Hollywood representation. Her critics remain unconvinced. I believe their skepticism toward Rodriguez’s perspective stems from the fact that everyone interested in posthuman and/or augmented, empowered human fiction in America today starts with seventy-seven years of superhero comic history as their main reference point. Imagine a future without the superhero. Imagine a future without the notion of a single person who can direct world history’s meandering river with unsanctioned activities that violate state sovereignty and ignore the rule of law. Imagine a future without the White male power fantasies that differentiate the superhero from the Gilded Age’s mystery men or Graham Greene’s quiet American. Imagine tomorrow as cosmopolitan cacophony, as an urban jungle gym where Asian Americans both support and oppose affirmative action, where Black Americans both support and oppose gay marriage, where gay men both support and oppose immigration reform, where Mexican Americans both support and oppose contraceptive mandates, where women both support and oppose religious freedom. Imagine tomorrow as remotely affected by today, and acknowledge that the superhero outlived his usefulness. The anachronistic Superman does not speak to individual aspiration, but to herd anxiety. Superhero films today comment upon unlimited power’s impossible paradox; Superman and his contemporaries personalize the unipolar American hegemon’s failure to establish justice and ensure domestic tranquility with Call of Duty martial advances at ready disposal via Raytheon and Lockheed-Martin. The superhero concept dramatizes White male power fantasy to express virile manhood through war and conquest; these figures of empire police unruly colonies populated with indiscernible aliens untouched by rational thought and Judeo-Christian order. Plot manifests from variable pacification success rates. The superhero’s great power lacks all sense of responsibility; it simply persists, unmoored from anything more complicated or complex than ‘punish the bad man who killed Mommy and Daddy’.

Adding melanin is no cure for unchecked militarism, fictional or otherwise; two Black Secretaries of State advised President George W. Bush before and during the Iraqi quagmire. Only rank racial tribalism exalts the need to view one’s own face in the corporate culture one consumes; this ethnocentrism leaves no room for critical examination of the superhero concept itself. Diversity initiatives in superhero comics fail because the superhero concept rejects human difference; every recent example of misogynistic cover art or fandom backlash against superhero cross-racial casting stems from general superhero creator/audience acceptance of the White male power fantasy as natural and normal. The term ‘Black superhero’ identifies a logical impossibility with a pejorative. Nerds of color who refuse to discard superheroes and wrangle superhero narratives with alternative reading practices to fit their politics and complement their group identities deny reality — there is simply no way to cast the Servant as Charles Stanhope.

Stanhope’s ethereal polish and command posture require chattel subjection. Reynolds’ portrait depicts a British nobility fueled by tortured adoration from broken children whose urgent pleas for respite from arduous toil and impassioned prayers for return to beloved parents go unheeded and unnoticed. The superhero is not a natural evolutionary step for reality or fiction; it’s a seventy-seven year old straight White male privilege delivery system. Those who believe superhero media’s reactionary excesses can be soothed with increased race, gender, and sexual orientation diversity wish only to substitute themselves for their oppressors, and combat nothing.

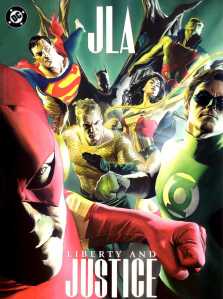

JLA: Liberty and Justice (2003), written by Paul Dini with art from Alex Ross

The DC Comics’ art from painter Alex Ross outlines the superhero concept today: in his JLA: Liberty and Justice, written by DC Comics’ animation legend Paul Dini, the Justice League characters feature smooth bulk and rounded brawn, adult muscle paired with primary colored paunches. Men are active but middle-aged, steely and determined, without care for clogged arteries or hypertension. Perfectly shaven with Brylcreem pomade and hip-hugging leotards, Ross’ work recalls Norman Rockwell’s America, where respectable Americans consumed conspicuously and segregation preserved decent communities. Like Matthew Weiner’s heralded Mad Men, Ross transports the audience to a postwar American economic success defended by flinty men with squinty eyes and absolutist ethics while readers enjoy safe genre futurism on every page. Batman’s cowl, tight enough to transmit facial expressions, locks into a perpetual scowl as he deconstructs villainous master plans. Ross’ Batman stands pudgy, comfortable; his grey contours testify to expense account living replete with three-martini lunches. Witness nostalgia as comic art, before Alcoholics Anonymous and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission wrecked the party.

Unknown artist, Dido Elizabeth Belle Lindsay and Lady Elizabeth Murray (1779).

Scone Palace, Perthshire, Scotland.

Ross’ antiquated Establishment action figures present the superhero self-image integrationists accept, defend, and then beg to subvert on the margins. It’s not enough. Brown palette swaps that color over George Reeves and Adam West recreations prove meager reparation for superhero comic whitewashing. This too, ignores history. Dido Elizabeth Belle Lindsay and her cousin Lady Elizabeth Murray appear together in a portrait from the late Eighteenth Century, friendly, enigmatic, and equal — to a point. Dido, in a Indian turban plumed with ostrich feathers and exotic silver satin, enters posterity an exaggerated Oriental, a perpetual foreigner totally without definition unless visually justified by non-Western affectations. The unknown portraitist does not imagine smiling brown Dido, a free English woman born from British imperialism, with the prim reverence afforded her cousin and countless other noble British ladies. The skin still matters. Today, art historians’ alternative analysis of Charles Stanhope, third Earl of Harrington, and a Servant interrogates the time-lost lives behind servile brown eyes, and speculates that this tortured gaze scans something past Stanhope’s shiny armor. Perhaps the Servant spies tomorrow, Jubilee, a new birth of freedom. We can never know. To my mind, Reynolds’ portrait allows superhero integrationists a prophetic metaphor: however difficult, look past the intended narrative of one’s age. Imagine tomorrow. Envision a world where your humanity depicts more than a detailed frame for someone else’s daydream.

_________

[i] “An Answer to the Question: ëWhat is Enlightenment?'” — Immanuel Kant, 30 September 1784

[ii] Esther Chadwick, Meredith Gamer and Cyra Levenson, Figures of Empire: Slavery and Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Britain, exhibition wall text, Yale Center for British Art, 2014

[iii]Stanhope sat for Reynolds two years following his regiment’s deployment to Jamaica to battle back French incursion that threatened Britain’s largest slave colony. — Esther Chadwick, Meredith Gamer and Cyra Levenson, Figures of Empire: Slavery and Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Britain, exhibition wall text, Yale Center for British Art, 2014

_____

The entire roundtable on Can There Be a Black Superhero? is here.

Shots fired

Thanks for linking to my piece, if only to dismiss my approach.:)

The thing for me is I can’t disagree with your analysis about the origins of superhero comics in white supremacist notions and the continued embeddedness of those frameworks in comics (and their film/tv adaptations). That being said, I believe in working with what we got, resisting through reading practice and artistic reworking individually and collectively.

Abandoning the superhero genre does not look like it is going to happen any time soon and I can’t imagine it doing must good given its pervasiveness in a shared (or at least imbricated) cultural dynamic. Instead, I’d rather work to provide and encourage the kind of reading (working towards, revisioning, deconstucting, reconstructing) that might serve the countless (so-called) nerds of color in navigating mainstream culture – and that I contend (in the linked piece and in other places) already happens to varying degrees.

Alex Ross: http://thecribsheet-isabelinho.blogspot.pt/2015/04/look-at-images-below.html

Great post, by the way.

So…I think James’ central point rests on the idea that the superhero is white supremacist because the excess power, the superness, is basically a metaphor for hierarchical power over people of color. Superman can fly because there are other people, over there, who aren’t allowed to walk.

That seems to dovetail with superhero’s links to the immigrant experience and assimilation narratives. Superman is white and powerful because he isn’t the Jewish Clark Kent; Steve Rogers becomes the blonde beast by ceasing to be the puny immigrant, etc. Empowerment is about rejecting/transcending marginalized identity and grabbing hold of whiteness.

There are a couple of possible counterarguments…but one big one might be that James doesn’t really think about the extent to which parody has been central to the superhero genre. Many of the best/most popular superhero narratives are parodies in one way or another (Batman 66 and Watchmen are two that come to mind immediately.) As a result, something like the Black Kirby project really remains in the central tradition of superhero narratives while explicitly exposing/mocking/reworking the relationship between those narratives and race.

I have to say that while I agree with Osvaldo in that the summations of the superhero genre’s origins and continued practices of white supremacy and racism (and sexism) are totally sound…the conclusion of the black superhero as a contrariety feels too defeatist, too fatalistic to justifiably apply in accordance to real world history and in the face of actual social change. Because at no point are the instances of progressive comic work, however inefficacious or vain in their attempts, ever brought up beyond the naming of a number of black heroes. Did Captain America: TRUTH or Green Lantern/Green Arrow #76 or Icon or Ms. Marvel just not happen? The industry has a long, long way to go in order to achieve true diversity and by doing so it will most probably have to upend the very foundation of defining what a superhero is and what their stories should be about. But I can’t see that as an impossibility in today’s fandom. There are too many outspoken fans and too many ambitious creators, however small their steps are being taken in, who are working and commenting on the works to be more progressive and are conversing about race to write off the whole of the medium as immovably white supremacist.

To me, it speaks to a larger myopia of our nation’s history in general. Yes, we still have a nation built on slavery that currently sanctions government to target black Americans, but that’s being directly confronted with right now as we speak. We’ve been through segregation and we’ve been through Jim Crow and we’re still going through those injustices in some institutions, but is the suggestion at the heart of this essay speaking towards a larger resignation of combating a socially destructive industry rather than working to make it better?

I almost hate to do this, because it’s the ultimate cheese-card, but I’ve gotta quote Dr. King in this instance as I feel he sums up the situation perfectly:

“The inevitable counterrevolution that succeeds every period of progress is taking place. Failing to understand this as a normal process of development, some Negroes are falling into unjustified pessimism and despair. Focusing on the ultimate goal, and discovering it still distant, they declare no progress at all has been made.

A final victory is an accumulation of many short-term encounters. To lightly dismiss a success because it does not usher in a complete order of justice is to fail to comprehend the process of achieving full victory. It underestimates the value of confrontation and dissolves the confidence born of a partial victory by which new efforts are powered.”

Everyone, thanks for reading and commenting!

@Osvaldo: The radical solution I propose here asks progressive superhero comic fans to examine how the integrationist approach has really served their interests. If progressive integrationist superhero comic fans want interesting superheroes of color that reflect their communities, they should admit that they’ve not found such characters in seventy seven years. No amount of altered reading practices will transform Cyborg into a fully realized human being; Robert Jones’ itemized list of grievances against DC Comics’ sexless characterization appealed to many because it was true; if we’re honest with ourselves, if we’re willing to sacrifice our fandom to reasonable appeals, we should admit that characters of color like Cyborg are the norm, not outliers.

I’m trying to avoid hyperbole here; this isn’t about policing other people’s fandom for me. But encouraging alternative reading practices for a racist genre searches for loopholes in Whites Only signs.

@Noah: Please explain in greater detail how parody helps navigate the dynamic I outline above. My argument is that the superhero genre cannot handle human difference because it requires exalted Whiteness to operate. The Enlightenment and British portraiture of that era offer useful parallel to the superhero: a single individual (straight, White, male) assumes superhuman or posthuman physical and mental characteristics, and applies them in service of public, prosocial activity. This only updates Kant’s interest in straight White men who assume the “freedom to make public use of reason in all matters”; in both, the primacy of the individual remains paramount.

Because of this, the superhero concept has no room and no patience for group identities and group politics. Race is too complicated for the superhero, outside of White male power fantasies. Slapping shoe polish on the Incredible Hulk makes no meaningful racial commentary; it’s just demeaning blackface that illustrates prejudices that characterize Black men as uncontrollable animals. Jennings and Robinson subvert nothing with the Black Kirby project; all we find here is a perverse example of Osvaldo’s ‘altered reading practices’ as comic art.

The Black Kirby project reminds us that superheroes of color are no more than racial stereotypes given artistic form to benefit straight White male audiences or straight White male characters in racial drag. Jennings and Robinson’s “Unkillable Buck” is crude and disgusting, but it’s not at all far from Luke Cage. To see this work as a meaningful subversion of superhero genre conventions that exclude people of color is to my mind, difficult.

@Donovan: Captain America: TRUTH was a horrible comic. GL/GA #76 defines heavy handed race talk (without ‘of color’ agency) in comics. Icon is a standard issue 90’s Superman pastiche weighed down by nonsensical character history and condescending Black conservatism. And Ms. Marvel is a genderbent Peter Parker in brownface for fourteen year old girls who don’t know any better. This isn’t “the industry has a long way to go”. This industry is utterly broken. Seventy seven years of superhero comic history and the best we can do is pull Icon out of mothballs to stand alongside Ms. Marvel as examples of White male story templates with minority race and culture details haphazardly slathered on like silly putty? Really?

You wish to make superheroes better on race? Stop buying them. Leave their stories on the shelves, ignore their merchandise in stores, and avoid sharing tidbits about their blockbuster movies. Everything else has been tried already. Tried and failed. This isn’t cynicism, this isn’t pessimism. I make public use of my reason and reject the notion that the superhero genre can remain itself and include me.

To enjoy superheroes as a person or color, as a woman, as a LGBTQ human being, one must compromise their identity on some level. I’d rather not. As Browning wrote, “E’en then would be some stooping; and I choose never to stoop.”

So, I think Ms. Marvel changes Peter Parker in important ways. The real racist part of Spider-Man (and other early superheroes, IMO) is the denial/repression of their ethnic content. Ms. Marvel is open about Kamala’s Pakistani Muslim background,and so can engage with issues of assimilation much more consciously and effectively.

The point about the Unkillable Buck is that it’s parodying superhero stereotypes of blackness. It’s saying what you are (at least in part) — that is, that superheroes are built on racist assumptions. But it’s doing that from within the genre, which suggests that the superhero genre, through parody, can maybe talk about these issues in ways that don’t exclude black people (arguably.)

I think Truth is a great comic that comes apart at the end…in a way that does unfortunately tend to confirm some of your arguments.

I can’t defend GL/GA. Those comics are crap.

GL/GA comics aren’t entirely crap in that I do find charming fun in how utterly unsubtle and outrageous they are. But I wasn’t exactly holding #76 up as THE sole beacon of anti-establishment writing. I still think the attempts are important…very important. It is in small ways anti-super hero. GL #87 Might be a better example. John Stewart has no interest in using his powers for any purpose other than to fight the type of real world evil he sees, which is racist senators. Again I’m not saying it’s a shining example of black characterization in super hero comics, but it isn’t stroking the ego of white readers in any way I find (expect for Denny O’Neil, I dunno).

I think saying Ms. Marvel is “genderbent Peter Parker in brownface” is especially condescending and reductive, not to mention false. Kamala is in no way an orphan who gets picked on at school for her intelligence, suffers indignities at the hands of her employer and the public at large or struggles to maintain balance between her costumed life and her civilian life, or in the case of the last point not as melodramatically. Are we calling all young costumed heroes Spider-Man now, just because he was the first 50 years ago? As Noah has said more than once, there’s an open consciousness with Kamala’s ethnicity and religion that helps the comic stand out over most other crime-fighting narratives.

I don’t see how TRUTH is a horrible comic except for maybe the end, and I won’t argue too much about Icon’s origins, but those are stories that directly involve the characters’ race in ways that reveal a level of true perception concerning the superhero genre. Maybe Icon doesn’t go far with it, but it is his conceivable background as a black conservative being brought into action by a young black teenager that people take to. It fires up imaginations, and though it doesn’t push the genre enough to where it could go, it pushes the genre.

My point is that people remember these stories where black or non-white identity were enthusiastically used to tell stories, American stories, that resonated with audiences of color. Maybe they’re all failures and maybe none of them make the reader realize how white supremacist the superhero genre really is, but that doesn’t take into account the audience who would pick up those books, see how they’re different and want to see something more along those lines because those stories resonated with them. People today enjoy diversity, true meaningful diversity, in their superhero books. People love how Kamala Khan never wants to hurt or destroy anything with her powers, or how at the end of Icon #1 he and Rocket are held at gunpoint by the cops they attempted to assist. That is diversity, diversity of storytelling by way of equal opportunity concerning the characters.

I appreciate you’re analysis and your perspective, as it really is incredibly insightful, but we’re not done with the genre. The road to meaningful equality is long, but not as long as you’re making it out to be.

Donovan, you may not be done with the superhero genre because you’re a fan, not because the superhero genre has respect for human difference. Women and people of color can enjoy superhero comics all they wish, but the narratives exalt White male power fantasy and nothing else. Progressives on race and gender and sexuality should recognize the limitations of this simplistic genre, instead of pretending that slow integration has ever produced meaningful narrative benefits.

And yes, Kamala Khan is a genderbent Peter Parker in brownface. Her first issue introduces Zoe, basically Flash Thompson in drag, whose concern trolling offers readers a mean girl confused by non-Western cultures but too ugly American to respect them. Kamala’s near-obliviousness to Zoe’s hateful commentary reminds me of pre-spider bite Parker, too comically good-natured to oppose high school idiots.

Further, Khan’s journey to Ms. Marvel parallels that of Brian Bendis’ Miles Morales. Both are so young the expected racial and sexual conversations their superheroism should ignite are sidestepped by their youth and inexperience. When Khan spends an issue swooning over Wolverine, when Morales learns how to be a superhero from 616 Parker, fans are supposed to find this heartwarming. I do not. Wolverine and Peter Parker know nothing about living as visible race minorities in their America. Khan and Morales should, but they are presented as so young and immature that their narratives avoid any serious race talk.

Icon makes no sense at all. Even if we suspend belief to read about an alien made to appear Black and male with Superman’s abilities who lived through chattel slavery in America just did nothing to dismantle that system, his choices as a superhero prove identical to every other White superhero ever made. Icon’s controlled by genre conventions on violence, and as a Black man he should know better. His ready interest in violence erases his authenticity.

The point? Accepting anything less than effective, realistic minority characterizations in superhero comics only encourages DC, Marvel, and all the smaller companies to ignore meaningful diversity, and illustrates that the superhero concept is to small and narrow to accept race and gender and sexual difference. It accepts straight White men in blackface as Black superheroes. These are fictional stories, not single-payer healthcare: if the road to meaningful equality is long here, in this space, then that road is not worth traveling.

The only reputable progressive position on the superhero advises abandonment. People who aren’t willing to go that far should examine whether their fandom has overruled their reason.

I kind of liked the Wolverine/Kamala conversation, in part because it’s not super clear to me that we’re supposed to actually think that Wolverine knows what he’s talking about. He advocates violence pretty straightforwardly; Kamala disagrees with him, and I think the book is overall on her side. I’d agree though that it would be nice to see a mentor who isn’t white, since that seems like it could and should be important.

I also didn’t think she was as blasé about the racial insults as you’re suggesting….I still haven’t read the Morales spider-man, so can’t comment on that.

After the first encounter with Zoe in issue #1, Kamala’s friend Bruno remarks “I hate her.” about Zoe, after she leaves. Kamala’s response? “But she’s so nice.” Nakia admonishes, “You’re such a baby Kamala. She’s only nice to be mean.”

Kamala persists with her defense of Zoe, and faces furhter admonishment from Nakia, who can perceive Zoe’s ugliness. Kamala’s left innocent, untouched really, by race. Kamala has to appeal to White audiences so she can’t start her story reasonably aware of other’s perceptions of her minority background, apparently. Kamala’s indifference to hate from a popular, blond antagonist is as we all know, straight out of the Peter Parker origin.

Look, I respect that most everyone does not want to turn their backs on the entertainment they enjoy. I get that. But instead of looking for loopholes, instead of searching for the one comic with a meaningful non-straight White male superhero, perhaps we can discuss whether my criticism of the superhero concept makes sense? If people agree with my discussion of the concept’s history and particulars, but refuse to accept the conclusion, that’s fine. But that decision requires more substance than “we should work within the industry” or “let’s work with what we have”. That’s tradition masquerading as good sense.

None of us are forced to purchase superhero comics. We need not enter the white space of the comic book shop every Wednesday. You don’t have to see Age of Ultron in Imax. If people are not willing to give up on superheroes and diversity, that’s a political choice, and if those same people accept a historical framing that at best can only produce questionable and marginal examples of respectable superhero diversity (none of which I accept, to be clear) then that political choice is not rational from my perspective, and requires further discussion.

Peter Parker’s not indifferent to Flash Thompson? He’s bitter about him and the others who harass him, isn’t he? That’s why he initially decides he doesn’t care about anyone and is going to make money for his family.

I do think that superhero comics are rooted in assimilation narratives, as I said — so I think the dynamic is somewhat different than the Reynolds painting (which is about already established groups glorifying themselves), but it’s related. I think the assimilationist origins give more leeway for discussing race than you’re perhaps allowing for—in Ms. Marvel, for one.

I also think the superhero genre is more innately white supremacist than some genres (like romance, I’d argue.) But…also less white supremacist than some (KKK genre fiction.) And I think there have been uses of the genre that deal with diversity meaningfully, though they’re mostly pretty far from the mainstream (Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis series, for example.)

But the thing is…most pop culture is white supremacist to one degree or another. My wife commented once that if she was going to only listen to non-sexist pop music, she would never listen to any pop music. It’s not just that people are fans and so blinded; it’s that I think people rightly understand that their options are limited in a white supremacist society in terms of finding pop culture that is not white supremacist. So…you make do to some degree. Like, even within comics, superhero comics hardly stand out as racist. Crumb, Herge, McCay, Asterix, really much of the underground tradition; it’s not hard to see problems even with Herriman and Schulz, really.

“. Kamala has to appeal to White audiences so she can’t start her story reasonably aware of other’s perceptions of her minority background, apparently”

I guess I’d point out that these comics are not documentaries.I’m not sure if raising an empirical question of whether a girl like Kamala exists in real life is the right way to approach the material.

However in this instance there is a similarity to Parker: why is Parker not aware that that cool jocks aren’t going to want to go to a science exhibit? In fifteen years on planet earth he’s wholly unaware of the existence of high school cliques? Nobody has ever chastised him for being geeky until he tries to befriend Flash Thompson? Was he born yesterday or something?

Just to expand my Parker point slightly people go through “fitting in with peer” issues during middle school, if not younger. Parker is in high school, unless he’s homeschooled he should have already learned Flash Thompson isn’t going to want to go to the science exhibit with him. But I’m not sure anyone cares if Parker is “authentic” in a documentarian sort of realism, why does it matter if Kamala is?

Yeah I was going to ask to what degree is the white supremacism in comics majorly different than most forms of America pop culture. Movies have black protagonists and Asian protagonists and Hispanic protagonists and non-white of all kinds (sometimes, admittedly rarely), are they too all propagating white supremacism in blackface? Certainly some of them do, but then you have others like the original Harold and Kumar movie.

How exactly is Kamala untouched by race? She’s dealing with it directly in the very first issue, even if she isn’t fully aware by how racism is coming at her. Should every 16 year old be fully cognizant of every single iteration of racial prejudice and bias that can come their way? We’re now at the point where racialized characters must fit through a pinhole of characterization, otherwise their sellouts. Which is ridiculous.

I mean the girl says “Zoe thought that because I snuck out, it was okay for her to make fun of my family. Like, Kamala’s finally seen the light and kicked her dumb inferior brown people and their rules to the curb.” with a rueful look on her face. This isn’t just the story of a Muslim character, but an American Muslim character. And like Noah said, the Peter/Flash comparisons don’t apply. Peter often wanted to kill Flash for the first several issues of ASM. He considered letting him die at the hands of Dr. Doom in ASM #5 and in AF#15 he’s swearing to himself “Someday I’ll make them pay! They’ll all pay!”. The characters are completely different because while both Peter and Kamala desire acceptance at some level, Kamala recognizes that she doesn’t want the acceptance of certain people, whereas Peter either wants acceptance or revenge as a substitute. So after all that, if you’re still gonna say “Kamala Khan is Peter Parker in brownface”, you’re not proving yourself knowledgeable of the material you criticize to fully illustrate your point and back up your claim/conclusion. I listed four recognizable examples of the Spider-Man comic’s makeup, and all you squeezed out was “someone was mean to her”.

And this isn’t meant to be geeky fact-checking to stroke a fan’s ego, since I am a fan. I very well may too close to the material to fully engage in deep criticism and acknowledge the flaws that make it crumble from a progressive perspective. But I’d like to think that the essay I wrote about black Cap portrays my willingness to take the genre at its face and confront the failings it contains when it comes to diversity, with my fandom on the line. But saying that the white supremacism is impenetrable, inevitable and will never cease to be so in the superhero genre speaks to the larger issue of white supremacism in our society and culture in general. If one element of pop culture cannot exist without it, the country can’t. And maybe it can’t, but you’ve yet to prove how it can never exist without it from now until the end of time, in the face of the times we’re living today where . It’s going to take more than purple prose and utter avoidance and dismissal of any example of non-white based storytelling to convince that meaningful diversity, and equality, within this genre is utterly hopeless. Has that proven to be the case elsewhere?

And FWIW going by the Letters pages in Ms. Marvel, Muslim women of all kinds, Pakistani, Turkish and others, find Kamala to be very authentic. And not just in a “We love to see Muslim superheroes!” but “We really appreciate the nuance you’re faithfully portraying that speaks to our life experience”.

So, I’m never really sure how much stock we should place in the proposed connection between the superhero concept and assimilation narratives. This argument always requires some acknowledgement of the personal racial and cultural identification of Siegel and Shuster and other early creators, and I find their backgrounds interesting historical tidbits, but less influential to the concept itself than their cultural products. I don’t think nearly eighty years of fanboys read Superman as a guy trying to become White, as someone who’s Whiteness is ever in question. Rather, Clark Kent and Superman emerge fully formed as White men in panel. There’s zero conversation or debate about Superman’s Whiteness in the context of his stories; he’s different because of what he can do as a White man, not because his skin and/or cultural sensibilities telegraph difference to those around him.

The Reynolds painting for me speaks to the superhero as colonial agent, the White male who defines masculinity through martial force applied to subject races. Superhero narratives concern the just and moral use of awesome, world-altering power by individuals, the same question that has plagued Western nations’ foreign policies since WWII. I make an intersectional claim about the superhero concept in the essay above, and etch a mechanism by which we can understand how race and gender and sexuality affect this genre’s conventions. Since the superhero concept promotes White male power fantasy for militaristic, hegemonic ends, there’s no place for human difference within the genre. This is the reason writers routinely fail to provide meaningful race and gender and sexuality difference in superhero comics.

So modern consumers should maintain a popular culture White supremacy threshold? Accept this much prejudice in the books you read and the plays you witness and the movies you watch, all of which you pay for directly, but no more? We pay for all of this. “Making do to some degree” accepts and encourages White supremacy, Noah. This is not progressive. This is failure. This begs for marginal treatment. This is no different than the Servant’s learned adoration of Charles Stanhope, taught through terrorism.

If the best defense for Geoff Johns’ Justice League is that it’s not Robert Crumb’s Justice League, if the best defense of the superhero is that other comics are worse, than its reasonable to reject all of these racist genres outright. People do not have to financially support hate.

One would think 14 year old girls would be the expert on whether a portrayal of a 14 year old girl is authentic, yet J. Lamb you wrote this:

“And Ms. Marvel is a genderbent Peter Parker in brownface for fourteen year old girls who don’t know any better.”

Why are we to believe you know 14 year old girls better than 14 year old girls who read Ms. Marvel?

“As slaves, Africans lacked any capacity for aesthetic sensibility, according to Enlightenment thinking.”

Any statement about “Enlightenment thinking” is of course going to be a simplification – nothing wrong with that – but this one is closer to being completely wrong than it is to being right.

“So modern consumers should maintain a popular culture White supremacy threshold?”

Yes. (That’s the correct answer, though of course I can’t speak for Noah.)

“This is not progressive. This is failure.”

Attempts at social progress necessarily end in partial failure. There are points beyond which striving for further perfection ceases to be productive and starts to cause serious problems of its own.

Anyway, it’s easy to demand that superhero stories be morally purified into non-existence, because they are commercial entertainment for white Americans. Making the same demand of a non-white folk art, on the other hand… it would still be wrong, but it would show a degree of courage of conviction (in liberal company, of course; but that’s mostly what the readership of this blog is).

“Why are we to believe you know 14 year old girls better than 14 year old girls who read Ms. Marvel?”

Well, this is just I guess, but I’d say for basically the same reason that the Party knows what’s best for the workers better than the workers themselves.

Pallas misunderstands my claim. I suggest that it’s easier to use characters like Kamala Khan and Miles Morales as superheroes of color because audiences do not expect children at their ages to possess and articulate sophisticated race and gender consciousness. They appear non-White in panel, but authors can pen stories with these characters where those characters do not display a mature understanding of the ways others can perceive their group identities. Kamala Khan in Ms. Marvel #1 is essentially pre-encounter; the initial exchange with Zoe confirms her as someone so interested in the assimilation narrative that they stand oblivious to majority disdain. Wilson uses secondary characters to provide the necessary counterpoint to Zoe’s bigotry.

This works for most, because many consumers will allow representations of young people to avoid race consciousness; in doing so, the audience itself avoids race consciousness. At that point, race exists as meaningless data, and the specific cultural and political histories attached to various races do not affect superheroes or their narratives.

So superheroes of color can enter into violent battles just like their White counterparts, thereby behaving just like their White counterparts, and no one has to care because race itself lacks meaning in panel. Kamala Khan’s one example of this; Miles Morales is another. But this carbon copy similarity in action and thought posits a general sameness of experience that race and gender and sexuality differences do not allow in the real world. This standard superhero experience for minority superheroes assumes that all people would respond to possessing extra-normal abilities in roughly similar fashion, by wearing gaudy skintight outfits and engaging in public battles that cause property damage and threaten civilians.

None of that makes sense if race and gender and sexuality are meaningfully rendered in a narrative. This is the enduring failure of Milestone Comics properties like Static Shock and Icon: if Blackness mattered to these superheroes, writersshould have applied different reasoning to standard superhero dilemmas than readers found in these characters’ stories. Icon’s a run-of-the-mill 90’s superhero saga with Booker T. Washington sensibilities thrown in for kicks: his indifference to reconceptualizing the point of a superhero makes his racial identification inauthentic, in my view.

These characters display varying attempts to square superhero genre conventions with meaningful race, gender, and sexuality identification in panel. The reason they don’t work is not because we ask too much to request meaningfully Black or meaningfully female or meaningfully gay superheroes. They fail because the genre itself inhibits such complex characterization. It’s not ridiculous for the buying public to request better than this, or to discard superheroes for their failure to render human difference.

Graham, I’d suggest that you check out Simon Gikandi’s brilliant Slavery and the Culture of Taste to learn more about Enlightenment perceptions on the capabilities of people of African descent. Thomas Jefferson was no outlier; many Enlightenment theorists promoted African intellectual inferiority notions within their works. Take Kant:

If you believe my take on the Enlightenment flawed Graham, please share your knowledge on the subject.

Recognizing the superhero concept as hostile to human difference does not present perfection as the enemy of the good, nor does it demand a moral purity of anything or anyone. The basic suggestion of all my superhero writing to date has been that non-straight White males possess a social richness worth examination in comics, and that superhero comics routinely fail in those examinations.

I really don’t blame the writers and artists and editors and fans; but all these constituencies support a superhero concept that abhors human difference and promotes White male power fantasies ad nauseam. The essay above attempts to explain why that dynamic occurs, and offers a meaningful response to that dynamic. No one need accept my solution or my articulation of the problem of superhero diversity, but it’s clear I’ve offered a comprehensive take on both.

Given what I describe above, incrementalism is not a virtue. People who wish for meaningful diversity in superhero media should boycott superhero media.

“If you believe my take on the Enlightenment flawed Graham, please share your knowledge on the subject.”

I cordially invite you to do your own work.

I’ll take the opportunity to note that hostility toward the Enlightenment is generally an inclination of conservatives, and of people who would be conservatives except for a non-economic grievance against the establishment, that is, identity politics (racial, gender, pr queer) or libertarian anti-statism (both in the case of Foucault).

“Given what I describe above, incrementalism is not a virtue.”

Nobody recommended incrementalism.

“People who wish for meaningful diversity in superhero media should boycott superhero media.”

You can’t have it both ways. If the genre is by nature racist, you can’t get “meaningful diversity” into it. You can either settle for perhaps somewhat ameliorating its inherent tendencies, or eliminate it altogether.

“You can either settle for perhaps somewhat ameliorating its inherent tendencies”

Better way to put it: You can demand that it doesn’t manifest its inherent racist tendencies too egregiously.

“So, I’m never really sure how much stock we should place in the proposed connection between the superhero concept and assimilation narratives.”

I don’t really think this washes. Superman’s literally an alien from outer space; that figures into a lot of stories over time as a problem/barrier/something to think about or resolve, one way or the other. Clark Kent, Steve Rogers, Peter Parker— the iconic characters are all elaborately weak/despised outsiders. Superheroes are disempowerment fantasies as well as empowerment fantasies (especially by the time you get to Marvel with characters like the Jewish Thing being presented as a despised outsider–or the X-Men, with all their troubles.)

Also…comics was, and has long been, a marginal genre. Maybe less so now, but comics have in the past had little cultural cred; they’re low status pop culture, as opposed to Reynolds, who was canonical because of his relationship to the powerful. So…I think the comparison between Reynold and superhero comics is provocative and interesting, but it’s doing a lot of work for you—more than I think your thesis can bear without at least some adjustment (IMO).

“Accept this much prejudice in the books you read and the plays you witness and the movies you watch, all of which you pay for directly, but no more? ”

I think if you don’t want to buy any of this stuff, that’s totally reasonable—but I’m really leery of moral purity tests. At least for me, I feel like there’s a line between saying, this comic is racist, and saying, anyone who buys this is tainted and suffering from false consciousness. The point I was trying to make was that, in a white supremacist system, there’s not a whole lot of pop culture to choose from that’s not going to be white supremacist, in one way or the other. Consumers, readers, creators react to that in various ways —by coming up with oppositional readings, by reworking white supremacist tropes, by starting their own companies and trying to make better things, even if they’re compromised. I’m reluctant to rule those out as reasonable options—even though, like I said, I also think just saying, “this genre is racist and not for me” is a fair thing to do.

“Anyway, it’s easy to demand that superhero stories be morally purified into non-existence, because they are commercial entertainment for white Americans. ”

Graham, this is false. There are lots of non-white comics fans. James is engaging them pretty directly throughout his piece. Not sure if you failed to notice that or what…but James really is not backing down from the more painful results of his thesis (including criticizing black creators.) So…you’re asking him to do what he’s already doing, and asking him in a really unnecessarily belligerent way.

The thing about the Enlightenment also—you’re being a condescending jackass. If you have objections, make them. James’ point about the Enlightenment being really extremely racist is pretty dead on, in my view. You don’t agree, disagree, but the pretense that you’re the smartest guy in the room gets really old really fast, and is especially unpleasant to witness when deployed in this particular context.

“Graham, this is false. There are lots of non-white comics fans”

Not the point. (The point being that nobody’s going to accuse you of attacking non-whites as a group because you attacked superhero stories as a genre.)

“The thing about the Enlightenment also—you’re being a condescending jackass. If you have objections, make them.”

Where? The part where I said he was wrong? Or the part where I declined to do what he could just as well do for himself? (I would say that is the opposite of condescending.)

First, it is the point if you’re criticizing Milestone Comics, which James does.