The index to the entire Joss Whedon roundtable is here.

_________

The most jaw-dropping moment in the lastest installment of the Avengers franchise, The Age of Ultron, was not a fight sequence or a CGI robot or even the relvelation about those creeepy twins. It was the discovery that Hawkeye/Clint Barton (played by Jeremy Renner) had a family. While the other Avengers made clumsy romantic overtures toward each other—particularly The Hulk/Bruce Banner (Mark Ruffalo) and Black Widow/Natasha Romanoff (Scarlett Johansson)—Hawkeye had been presiding over an ubertraditional domestic scenario in his other secret life, complete with two towheaded kids and a pregnant wife, Laura Barton, her countenance alternately radiating farmfed good health and requisite worry (the longsuffering Linda Cardellini).

Though the scenes at the Barton homestead are certainly meant to provide peaceful and occasionally comic intervals between the Avengers lengthy and elaborate battles to save the world, they feel tacked on, inauthentic. What I suspect Whedon was attempting with the deepening of Hawkeye’s character was to make him more interesting (since, let’s face it, his powers are sort of underwhelming) and to add another dimension to the franchise. It’s an age old saw that superheroes can’t have so-called normal relationships; the friction between their everyday lives and their secret identities simply do not allow for it. Getting involved with normals—usually women, since most superheroes are men—can compromise their vocation and make them vulnerable on too many fronts. Thus Hawkeye’s family had been kept secret from the Avengers, so that neither friend nor enemy could put them in danger.

This vision of radical solitude, of permanent singlehood, could be seen as progressive: the hero, fighting always for the greater good, is unencumbered by the domestic relationships and mundane activities that traditionally bind people together. Yet even in his early days, Whedon never took that stance. The Avengers, after all, are a mock family of sorts, and in that they are a natural progression from the Scooby gang of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Though the gang coalesced around Buffy and her superpowers, by the end of the series nearly every member of the group had some sort of power, an identity he or she had to hide from the world at large (though Xander’s occasional military knowledge, a residue left in his brain after a Halloween episode where he transformed into a mercenary, was always a little suspect).

Over the seven seasons of Buffy, we watched her struggle with The Big Bad, with her powers, with her vocation, and with her family and friends. We also watched Buffy, Willow, Xander, and Giles take on and lose several romantic relationships. Though the first few seasons of the series relied on Buffy’s ill-fated romance with the vampire Angel as an analogy of adolescent relationships, the transformation of Angel into a good vampire eliminated much of the tension that fueled their attraction. Buffy’s subsequent relationships, with the buff-but-boring Riley (who turned out to be involved in a nefarious proto-military project), and then with the reluctantly reformed vampire Spike never quite reached the intensity of feeling of that first time with Angel. When the Spike attraction began it was clearly for a bad boy, and definitely had Buffy dealing with the complications of sexual attraction for someone she really didn’t like or trust. It dovetailed quite nicely with her feelings of alienation upon being brought back to life by her friends; exiled, as it turned out, from a place more like heaven than hell.

The other romances we watched play out on Buffy ranged from poignant to the stuff of romantic comedy. Willow’s high school boyfriend Oz, who conveniently turned out to be a werewolf, joined the group without too much hazing. It was rougher when she fell in love with Tara, not only because Tara was a woman but because she was a witch, and the couple’s dabbling in dark magic went from a hobby to a dangerous obsession. Xander’s only real girlfriend after years of an unrequited crush on Buffy, the former vengeance demon Anya, had a harder time assimilating into the Gang, in part because of her rather abrasive personality. And after his girlfriend, a computer teacher at Sunnydale High with gypsy roots, is killed fairly early in the series, we don’t see token adult/sometime watcher/school librarian Giles do very much socializing. In fact, when he leaves to return to his native England it feels appropriate, like he should really stop being an old guy hanging around with a bunch of college kids.

The solidification of the Scooby Gang as a proto-family reached its apotheosis with the arrival of Dawn, Buffy’s younger sister, who suddenly appeared on the show several seasons into its run. What began as a WTF moment slowly unfolded into one of the most complicated relationships on the show, as everyone became protective of Dawn but Buffy retained the resentment that older siblings generally have for younger ones. Don’t touch my stuff. Stop hanging out with my friends. GO AWAY!

Among Buffy stalwarts it’s generally agreed that the scariest episode of the show has nothing to do with the supernatural, and everything to do with domestic life. In “The Body,” Buffy comes home to find her mother, Joyce, is dead. Her death, sudden but of natural causes, cannot be undone by any spells. No magic, no books, no wishes will bring back her mother. In facing the abyss of grief, Buffy, who has already seen so much death, is forced to deal with the most mundane aspects of life: taking care of her sister, getting a job, housekeeping, and muddling through without the person who had always quietly been there for her, even when they had the usual (and unusual, since she is a Slayer) mother-daughter disagreements.

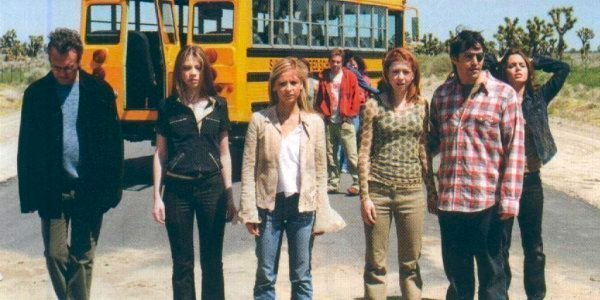

In the final season of Buffy, for reasons too complicated to get into, the Scooby Gang has to mobilize once again to save the world but this time they have another agenda: they must protect all of the potential slayers (the brief backstory here is that when the Slayer dies, a new one is called). Thus Buffy and the Scoobys end up running a kind of a training camp for adolescent girls, many of whom resemble Buffy was before she was annointed: bratty, selfish, mopey, whiny, and scared. It would be an overstatement to claim that in raising up her army Buffy takes on a maternal role, but she does take on the persona of mentor and leader.

And it’s this final incarnation of the Gang, which is a family bound by something stronger than blood and far less sentimental than traditional domesticity, which fights the ultimate battle of Buffy. It is much more satisfying, and progressive than anything Whedon has come up with since: an army of adolescent girls, led by an extraordinary young woman and her friends, who have gradually grown up together and discovered their own distinct powers, bestowed on them in part by fickle gods, but mastered largely through their own maturation and machinations. It is more thrilling, dangerous, and emotionally charged than any Avengers battle could ever be.

A million times yes to all this – and thanks for putting in such specific terms why the focus on a heteronormative, exclusionary definition of motherhood in Age of Ultron felt like such a gut punch. Buffy (and Angel, and Firefly, and even Dollhouse) all feel like celebrations of non traditional families, the reversion to the nuclear ideal in Ultron felt like a particular letdown.

Plus I like that (unlike me in this comment) you’re framing all this in positive terms: showing how and where something can be really interesting rather than bemoaning badness. There’s a place for both, of course, but I always appreciate the upside.

the chosen one/chosen family of Buffy and JW’s other shows always resonated w me. I really liked that Willow and Tara moved in and helped w Dawn while Buffy was “away”. The cohesion of their family centered around Buffy but it still existed while she was gone. I just wish Buffy had been paid for her labor. Like what’s the deal w the Watchers Council not paying her? Seeing her struggle with bills and having to get a job def served a purpose in that it mirrored real life and young adulthood, but also slaying was her job and it’s insane that it wasn’t shown that way.

I’m guessing the Watcher’s Council is secretly broke. Maybe they tagged along in Operation Musketeer, hoping to get their hands on some Egyptian artifacts, and Eisenhower cut off their funding.

It’s striking, comparing Buffy and the Avengers, how the Avengers is so heteronormative? unimaginative? conventional? If you’re going to have Barton be essentially closeted, why couldn’t his SO be a guy, as just one example. Buffy had LGBT characters, BDSM relationships, unconventional family structures, heroes who weren’t guys. It’s an effort to tell an unconventional superhero story, in a lot of ways—and then the Avengers just goes back to being conventional.

it’s interesting too that it’s television which is the more innovative and flexible in this instance.

There’s an episode in I think season 5 (maybe 6) where Tara’s family comes to town and tries to “take her back”. They say Tara’s supposed to suddenly turn into a demon now that she’s reached a certain age, which is what has happened to all the women in the family.

Turns out it was just made up by the men of the family to keep the women in line. When Spike reveals the lie, the men start to get physical and Buffy says if you want to take Tara back you’ll have to go through me. The rest of them say the same thing in a very Spartacus way. And it ends with Buffy saying Tara’s part of their family now. So yeah, they rather explicitly say the gang is a family.

And as I mentioned in another Whedon roundtable post, I really like the finale; especially the somewhat cliched ‘hero is seemingly cut down, only to summon the strength to get back up and kick ass’ moment which inspires the rest of the women to turn the tide of the battle.

I found The Body moving and true, having gone through a lot of deaths in the family not long before I saw it, especially for one thing: the Scoobys, Buffy’s surrogate family, standing there in so many scenes, not much to say – clear on their faces their grief for Joyce and their friend Buffy and her loss, not knowing what to say.

Further on the non-traditional family front, my sister like to say that a very major theme flowing through the show is Fathers and Daughters, what with the Giles/Buffy surrogate relationship contrasting Buffy’s non-relationship with an always absent biodad. It’s reflected nicely in Faith’s dark mirror relationship with the Mayor, a pair that, incidentally, had tremendous chemistry. Faith was never more appealing in my eyes than in a dowdy flowered dress, enjoying the (comically wholesome) affection of her outlandish mentor.

Faith and the Mayor are adorable together – though come to think of it, that’s another example of Whedon’s strange tendency to revert to the mean in gender politics. (Bad girl just wanted daddy!)

I’m a bit proud of myself that I didn’t think much of “The Body” even as a young and impressionable teenager when it first aired. It’s not a talent for serious realism that made you famous, Joss; no special credit for a journeyman essay merely because you put it in a genre show where we usually don’t see that kind of thing.

But was it Bad Girl just wanted daddy, or Bad Girl needed a daddy? [shrugs] It certainly brought out something appealing, for all the murder, a path she was, however, already on…

Barton’s family is straight out of the Ultimates line of comics, where much of the first Avengers film was from too. I’m not really surprised that Marvel, owned by Disney, played it safe. Because they aren’t going to play fast and loose with the big money maker. Look to Ant-Man and the smaller films for places where the norm may not be embraced.