John Jennings seems like he’s got superpowers himself, he’s involved in so many projects. He teaches at the University of Buffalo. He’s involved as a curator of the Black Comix Arts Festival. He collaborates with Stacey Robinson on the Black Kirby Project; he’s just co-edited a new book about black identity in comics called The Blacker the Ink, and he’s got about a bazillion other comics projects he’s working on.

And as if that’s enough, he took time out to talk to me about black superheroes, Jack Kirby, Blade, Power Man, and Captain America’s black sidekick (not that one). Our conversation is below—part of HU’s ongoing roundtable on the question of Can There Be a Black Superhero?

______

‘Night Boy’ created by ‘Black Kirby’ (John Jennings and Stacey Robinson) and Damian (Tan Lee) Duffy

Noah: What do you like about Kirby, and what are you less fond of?

John: I think it’s more liking than disliking. I remember being a kid and not being attracted to the work and all. I felt like he was destroying the characters that I love so much. Because, his work on Captain America, as a kid, it looked blocky and crazy looking and abstract. But for some reason you notice the work and you’re attracted to. And as I got older I started to realize, this guy was actually creating some of the conventions, as far as how superhero comics are done.

And then when we started working on the Black Kirby project, we started to realize how experimental it was. I remember reading this interview about the Black Panther. And he said he felt like his friends who were black should have a black superhero. And he did create a character who was African and not African-American. Instead of creating a black character that would be from his own country. And also the fact that Wakanda doesn’t actually exist.

I thought Don McGregor’s run on Black Panther was in some ways really progressive, and then we turn back to Kirby and it becomes this weird cosmic odyssey thing with this monocole dwarf guy. It’s really strange. It’s this odd thing to happen after a story grounded in progressive ideals. Because McGregor had him fighting the Klan, and he was in Africa helping out his people, which was great. But I think Don McGregor as a writer has always been a lot more connected to the ideas of the black subject.

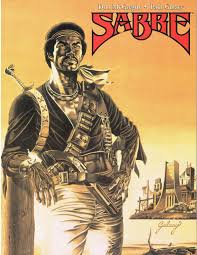

If you look at something like Sabre. Sabre was centered in a post-Apocalyptic world, and the main character was an African-American man. And he was in an interracial relationship with a beautiful white woman. Most of it was about him trying to protect his family. It’s interesting because the character —he looked like he was loosely based on Jimi Hendrix. He was very swash-buckling, always musket and sword in hand. Had this pirate feel to it. It was a funky book, and this was Don McGregor.

Paul Gulacy and Don McGregor

Yeah, I’ve been trying to read his Power Man. Which, I feel like he’s much more conscious of racial issues. He has a hooded Klan like supervillain attacking a black family who’s trying to move into the suburbs. The writing’s just hard to get through. It’s not written very well.

Right—as far as—that era. If you reread the Essential Power Man, it’s bad.

It’s overwitten and it doesn’t make any sense and the dialogue’s a mess.

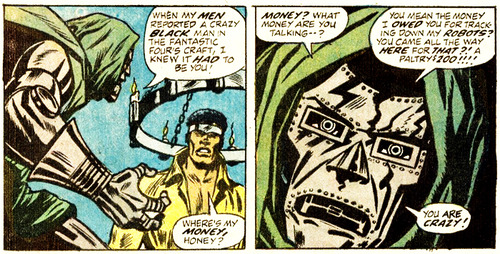

Have you seen Jonathan Gayles documentary White Script, Black Supermen? Gayles is a cultural anthropologist. The impetus for him creating the documentary was this one story where Luke Cage tries to get $200 from Doctor Doom. And he was totally disgusted by the fact that this guy was just a hustler. And that was part of the dissonance. You have a black reader, and this is the first African superhero to have his own book. He is also an ex-con. And he is not necessarily really a superhero, he’s a mercenary. And he’s working in the hood primarily, adn his villains aren’t really well thought out.

Steve Engelhart and George Tuska

They didn’t really understand what they were talking about with that particular character.

Race in superhero comics was really strangely handled early on. Because it was directly related to blaxploitation films. Superhero comics are very reactive and they are a business and they see trends and they try to jump on top of them. And that’s pretty much what happened. That’s where you get characters like Shang-Chi, who was pretty much Bruce Lee.

So, I’m wondering, given the inauspicious start with black superheroes, why are black superheroes important. Or why do you still care about them?

It’s interesting, because the superhero as a structure, it’s an old idea. From the 1930s. I think it’s important for people who participate in society to see themselves as a hero of some kind, or to see themselves in a space where they feel that they can connect with popular culture.

Because popular culture is our culture. That’s a lot of times the first time you see or recognize yourself is through the popular media you watch. I know it affected me as a kid coming up, watching pulp fantasy stuff and reading these things.

And honestly there’s a lot of serious issues with superheroes as a genre. It’s hyper-violent, it’s misogynist, it’s just very sexist, it’s kind of homophobic. But it’s ours; it’s our thing. It’s an American construction. And I understand why it exists—and it does mean something when you’re not there. I think that’s the thing; there needs to be representation, as far as a diverse array of representations. And written from the right standpoint as well.

And honestly I think it’s more important to have black creators working than it is to have black superheroes. Because there’s a handful of black writers in the mainstream. One of the most important books —I don’t know if it’s going to get canceled, but the new Ghost Rider book. A Latino character, a Latino superhero, written and drawn by two African-American men. That was unprecedented; I don’t think people really knew that that was happening. And it’s Marvel.

I think there’s something about just how dominant the superhero is right now. As I think it really is as popular as it was in the 30s. It’s just not in the comics.

One of the thing that bothers me, is that people say what kicked off the trend was the X-Men movies. But it was in actuality the Blade film. It was 1999, and that predates the X-Men movie.

How was the Blade film? I haven’t seen that.

Blade is awesome. You know why I like Blade? Because it’s a Blaxploitation movie with vampies.

That sounds pretty good!

It’s a fun movie. I don’t know how much of this is legend and how much is truth, but Wesley Snipes, he wanted to be Black Panther. But they wouldn’t let him do Black Panther, so he was like, what else do you got?

So they gave him a C-level character. No one knew who Blade was. I knew who Blade was because I used to read the reprints, but he was kind of a lame character. He had these green goggles, it was a dumb character.

But he translates really well to the screen. THe’s pretty much a martial artist, and Wesley Snipes is an amazing martial artist, he’s a 5th-degree blackbelt. So he choreographed the entire movie. It looks great. It’s out of control crazy.

My friend Sundiata Cha Jua, a historian, says that after Blade was successful, Marvel began to take over the franchise. When you watch the first film, it’s a very “black” movie. He relies on this serum to prevent him from becoming fully a vampire, he’s a daywalker. And if you look at the first movie, he gets his serum from this Afrocentric incense store. And he’s in a community of black people and they know who he is. And I thought that was really important.

But when it starts making more money—because Blade made a lot of money. They start to dilute his connection to the black community. And they start erasing him from his own movies. And as I recall, I think Wesley Snipes took them to court over the third movie. Because he’s barely in it. It’s Ryan Reynolds and Jessica Biel because they were trying to create a spin-off to Midnight Suns or something like that.

Or you look at Stan Lee’s movie, his documentary, which I enjoyed. But again they don’t mention Blade as the jump off for the Marvel scene. Or for the Marvel franchise. Stan Lee did not create Blade. Gene Colan and Marv Wolfman created Blade. So it doesn’t make sense for him to be in Stan Lee’s movie. But it’s false to say that the X-Men jumped off this franchise.

I saw a couple of articles, like, hey, don’t forget about the Blade movie.

Is part of the problem with getting more black characters and more black creators is that the superheroes are so centralized in Marvel and DC? There’s so much energy and interest in the big two, that the only way to get a black superhero is to make Captain America black, or something like that.

I have to back up a little. I’m interested in the mainstream characters. As an exercise, I think Black Kirby works because it’s making fun of the superhero genre, and bringing in black power politics. It’s celebrating Kirby but also critiquing him. And it’s interesting as a visual exercise, or as a critical design project. But honestly I don’t have that much interest in mainstream superhero comics as far as black expression. I’m really not satisfied with what I’ve been seeing.

Or the characters who I really like, they screw them up or they do something wrong with them. Like, Mr. Terrific, I love Mr. Terrific, but his book was awful. I think the more interesting things around diversity are happening in the independent black comics scene.

Because it’s not just superheroes. It’s all these different types of genres; there’s action adventure, like Blackjack. There’s stuff like Rigamo, which is magical realism gothic fantasy.

Che Grayson and Sharon De La Cruz

So with mainstream comics there’s issues around nostalgia. Nostalgia is a very powerful thing. So not only do they want to be accepted by the mainstream, but they want to make a monthly comic book. It’s very difficult to do that when you’re flipping burgers or you’re teaching a class here or there trying to make ends meet. It’s a very differnt model. I want to tell them, no, make books about your expeirence, and put them out when you can, because you’re not DC.

It seems like there’s a problem with nostalgia and superheroes for black people, since black experience in the past was often one of oppression.

The 1930s when the superhero were created, the first black characters were extremely racist. You had characters like Whitewash who was Captain America’s sidekick, and his superpower was that he always got captured and had to get rescued. He was in blackface and he had on a zoot suit.

Whitewash Jones was created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. His dialogue was often written by Stan Lee

And of course guys like Ebony White from the spirit. They’re based off how the black image had been constructed in minstrelsy and other racist propaganda. Even advertisements and products that were being generated had these extremely derogatory, hyperbolic stereotypes. So illustrators when they draw the pantomime of a black image, they’re drawing from the Jazz Singer directly.

I’m curious about what you think about the fact that one of the things for the superheroes is it’s about law and order.

I think it’s about justice. That’s the thing—my favorite superhero is Daredevil. I totally related to this kid. Because I was bullied, and i was poor, and I thought I was smart—I was pretty smart. I just related to that character, and he was a fighter, and I liked that about the character. More than anything, I just loved the fact that he was too stupid to quit. I loved that. That’s his real superpower, and that’s an interesting life lesson to pick up. Don’t give up. I’ve seen many stories where Daredeivl would have died if he just gave up. But he couldn’t because his father taught him not to. I thought that was awesome.

Yeah there’s this thing about law and order, but they’re vigilantes, and they’re saying, in this resounding voice, I have the power to make things right. A lot of people were really upset when they saw Captain America punching Hitler in the face back in the day. They’re violent characters. And they’re reifications of a particular type of jingoistic urge. But they’re ours and they love them.

I love superheroes. And I hate superheroes at the same time.

I think that most folks who don’t understand how these problems in our society actually manifest think that if I do this “one thing” then the problem is fixed. It’s a very Western way of thinking. We are taught to think about the “object” and not the “system”. So, making one African superhero is awesome but, what about the systemic issues around the disparity in the first place? It’s the same problem with integration in our country historically. Our country would put “minorities” in a white space to prove a point or to illustrate a law. It hardly ever thinks “once they are in this space have we really provided a place where they can grow and flourish”. It needs to have this token example to say ” Yeah. It’s messed up in our country but, look at this ______________. See? We got that issue covered.”

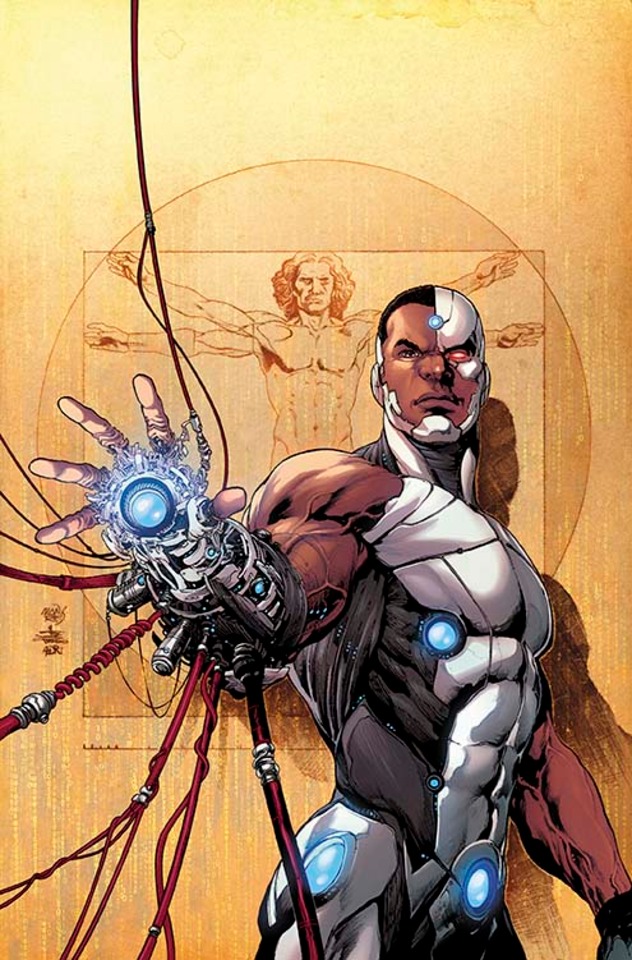

So now. We have a black writer (David Walker) on a black superhero at DC (Cyborg). Let’s see how it pans out. David’s a good friend and great writer. Should be exciting!

Art by Ivan Reis and Joe Prado for the new Cyborg series

Agreed, the Mr. Terrific comic was HORRIBLE.

Were there problems with the handling of race, or was it just generally bad?

Ha, never heard of Whitewash Jones. Kirby loved designing kid gangs, huh? Anyway, you’ll all be pleased to know that the crazy racism has been retconned out:

“It has been revealed that a lot of the Young Allies wartime adventures were made into a comic book as propaganda for the United States to earn support in the war effort, especially among young impressionable people. The comic book, while based on true events where often times embellished, and sensationalized.

[…]

The least flattering portrayal of any of the Young Allies was the character based on Washington. Renamed “White Wash Jones” the character was a dimwitted, racial stereotype that was modeled after a minstrel show. While considered socially acceptable at the time of their publication, Washington’s portrayal would be considered greatly offensive by todays standards. At the time of their publication, Washington considered his portrayal as ridiculous. Although he would note that he had been treated worse when off duty, he remarked that “You could tell that those writers have never been up town”.”

Problem solved, then. Excelsior!

I hate that “considered socially acceptable” rhetoric. What it means is “socially acceptable” to the majority of white people.

They’ve retconned it out…but they still have to make the “of its time” defense.

That’s some sorry shilly-shallying.

To answer your question Noah, kind of both. From what I recall it was just badly scripted with awful dialogue and made Power Girl out to be his girl on the side, infuriating his black love interest.

http://www.craveonline.com/images/stories/2011/2011/September/comics/dcnew52/mrterrific/mrterrifickaren628.jpg

I dropped it after the first issue, but here’s a review that gets into what made it annoying.

http://www.craveonline.com/comics/reviews/174400-new-52-review-mr-terrific-1

I’d probably have much more sympathy for the sentiments expressed in this interview were this particular assumption discarded. Osvaldo’s made similar points, among others. I remain a skeptic: how can people of color in the West regard superheroes as ‘our thing’ when we routinely find horrid bigotry and inhuman prejudice directed against us within superhero comics? How does that make sense?

For me, it does not matter if Marvel Comics erased Whitewash Jones’ obvious minstrelsy in modern stories in favor of hazy Greatest Generation nostalgia. The fact remains that no era of superhero storytelling persisted without massive reliance on racial and sexual stereotypes in panel. Chris Gavaler reminds us that superheroes owe much to the iconography and public marketing of the Ku Klux Klan; my own work discusses the superhero concept’s reliance on Enlightenment-era anti-black prejudice. How much more evidence do we need to conclude that the superhero concept is fundamentally hostile to human difference, and therefore hostile to people of color at its core?

I can understand the desire some have to take part in their societies’ popular culture, but to do so at the expense of their political identities seems unwise. The genre that produced Whitewash Jones cannot respect people of color and recognize itself. Many can applaud the continued employment of minority creators of color in comics, but the idea that people of color should continue to support, patron, and create material for the genre that gave us Luke Cage, Power Man strikes me as ridiculous. No one should ask Black men to join the Klan as dues-paying, cross-burning members to reform the Invisible Empire.

Recognizing the misogyny, sexism, homophobia, and racism of the superhero genre does not go far enough. Expecting comic creators of color to reform the genre does not go far enough. Buying tickets to Marvel’s latest special effects-laden spandex bro-down while tweeting one’s desire for a solo Black Widow or Storm movie does not go far enough. When people support superheroes, they support a concept where one person, usually a straight White male provided extraordinary physical and mental privileges on top of his racial and gender ones, alters the world in his image. Further explanation is required to convince me that any of that dynamic could possibly be considered “our thing” by those marginalized by Western societies today.

I don’t buy this idea that sexual stereotypes or misogyny are an inherent part of the superhero genre. Anyone suffering under this delusion should read one of the better crafted superhero books with female characters such as The Adventures of Superhero Girl by Faith Erin Hicks.

Well, I wrote a whole book about Wonder Woman as feminist theory, so obviously I agree to some extent. And there’s Sailor Moon…

I think for various reasons the superhero genre has been more successful at dealing with gender than with race.

Pallas, I think it depends on whether one allows for the possibility that any possible human prejudice is an inherent part of the superhero genre. I think sexism and racism and all manner of other bigotry exists within the superhero concept. Given this, for me the question moves to how moral individuals should handle the superhero genre’s inherent prejudices.

But the existence of one or two superhero narratives with strong female characters does not negate superhero sexism. People keep looking for loopholes to maintain their appreciation of a flawed and bigoted genre, one we all admit overflows with examples of disgusting stereotypes and art that speaks contempt toward human difference. There’s something wrong when we look at side characters like Whitewash Jones as aberrant quantities, however often they appear, and never regard them as basic and fundamental to the genre’s narratives.

Now, no one’s obligated to agree with me on this; if you don’t believe that sexism is inherent to the superhero genre, that’s fine. But I’d certainly like to read your reasoning, Pallas. Put another way, longer than I’ve been alive women in superhero comics have been treated as empty-headed fetish objects by comic writers and drawn as silicone-enhanced adult novelties by comic artists. Why should The Adventures of Superhero Girl by Faith Erin Hicks force us all to discard the vast majority of superhero genre female representation to assert that the genre itself holds no fundemental prejudice toward women? I don’t get it.

Well, for me, there’s a question of history vs. structure. It’s clear that superhero genre work has been mostly sexist…but that’s really true for lots and lots of genres. There are a bunch of high profile, very successful uses of the superhero genre that are women-centered and explicitly feminist in various ways—the first Wonder Woman comics, Buffy, Sailor Moon, Ms. Marvel. Showing empowered women kicking butt just isn’t a huge problem for the superhero genre, as far as I can tell—and even fairly complicated takes on gender, violence, and power seem possible.

Race is a different matter. In the first place, there isn’t really a similar record of high profile popular and aesthetic successes, IMO. In the second, I think there are a number of structural aspects of superhero comics which make engaging with race difficult. The genre’s themes of assimilation and of law and order, and it’s resistance to stories of social change, all make it very hard to create narratives that deal with race in sophisticated or thoughtful ways.

“Why should The Adventures of Superhero Girl by Faith Erin Hicks force us all to discard the vast majority of superhero genre female representation to assert that the genre itself holds no fundemental prejudice toward women? I don’t get it.”

Well, let me put it this way. For you, I’m guessing when you think of the superhero genre you think of a certain canon of books: if I had to guess, I’m guessing you have in mind whatever sells the most, or everything Stan Lee ever wrote or the worst of the new 52 excess or whatever.

But, for me, I think of the canon of whatever I appreciate the most. For me, female superheroes bring to mind Cardcaptor Sakura, or The Adventures of Superhero Girl, or the charming prose novel Velveteen Vs. The Junior Super Patriots, or the digital comic Bandette, or Jim Rugg’s Street Angel miniseries, or maybe even the Powerpuff Girls. There’s Takio by oeming and Bendis, or the Teen Titans animated series. There’s the new Ms. Marvel, or the Brian Vaughan written Runaways issues. They’re all fine.

For the sake of argument, if you are correct that most superhero books are misogynist (though I suspect this might be a bit of a stretch), the problem is not so much the genre, but the fandom that embraces crap and ignores quality books. But that isn’t the fault of the genre itself. That’s a problem with fandom.

Oh and in response to the “empty-headed fetish objects by comic writers and drawn as silicone-enhanced adult novelties by comic artists” comment, there is a tradition of female heroes aimed at girls that go way back. Mary Marvel got her own comic in 1945, and it had its moments. Obviously as Noah would attest, Wonder Woman had its moments as well. I’m sure there’s been Supergirl stories with a good deal of charm.

The issue isn’t whether those comics are 100% perfect or anything, but your dismissal of the genre’s treatment of women seems way too harsh.

I’d suggest that instead of explicit feminism, the works you’ve cited present attempts at feminism undercut by male expectations. I don’t wish to stray too far from Jennings’ words above, but I find love interests like Tuxedo Kamen, Angel, Riley, and Spike complicate the feminist narratives of Sailor Moon and Buffy. Sailor Moon’s utterly devoted to a reserved, aloof male figure in Tuxedo Kamen, and Buffy, the product of a single parent home headed by a working mother, perpetually seeks acceptance from strong, rebellious, and damaged men throughout the series. Others are free to call these works feminist. I have trouble with that assertion.

Superheroes present conservative stalwarts, people who wish to maintain the status quo’s reliable order and stability. If people of color have difficulty engaging such perspectives in a believeable fashion in superhero comics, part of that involves the reader’s disbelief that people of color could possibly support a status quo that promises reduced living standards and economic opportunities for members of race minority groups in comparison to their White counterparts.

But we see ‘of color’ conservatives defend that status quo all the time. Black conservatives like Mia Love, Tim Scott and Allen West promote law and order conservatism while liberal Black elected officials embrace law and order sentencing policies to expand the carceral state within urban minority communities. To my mind the problem isn’t really about law and order; the problem involves cultural imperialism. Jennings himself touches on this above; the sense of justice portrayed in mainstream superhero narratives usually involves a solitary figure who employs violence to mold the world into something that resembles his own ideals. Batman beats up the poor and indigent to pursue justice in Gotham, Daredevil beats up the poor and indigent to pursue justice in Hell’s Kitchen.

Black superheroes conform to this dynamic, because the superhero concept itself does not allow non-straight White male characters to imagine or develop or express alternative justice ideals, even when these characters represent communities with different perspectives on what justice looks like. Luke Cage and Cyborg and Green Lantern John Stewart all parrot the rugged individualist vigilantism of their White counterparts, because seventy seven years of superhero comics cannot imagine superheroes who reject the “individual who changes the world” genre foundation. Women, people of color, LGBTQ folk: all these groups have experience with institutional control and state sanction; the assumption that heroes from these communities would display an identical disregard for collective action as White male superheroes do strikes me as the real reason non-straight White male superheroes always present as an incomplete, false quest for pure truth.

But try as some might, in seventy seven years we’ve yet to see a re-conceptualized minority superhero who rejects the logic of world-changing solo action, much less superhero violence. So no, it’s not easier somehow to generate feminist superheroes in comparison to race minority superheroes. What’s more likely is that some of the same people who take no offense to the logic of world-changing solo action as performed by White male characters maintain that comfort today when reading the world-changing solo exploits of White female characters.

@ J. Lamb

“Sailor Moon’s utterly devoted to a reserved, aloof male figure in Tuxedo Kamen”

This applies to about one half (the first half) of the first season of that show (and then only if we understand that “utterly” doesn’t mean utterly at all).

“male expectations”

Has anybody yet gotten around to telling Stephenie Meyer that she’s a man?

@ Noah

“The genre’s themes of assimilation and of law and order, and it’s resistance to stories of social change, all make it very hard to create narratives that deal with race in sophisticated or thoughtful ways.”

Insofar as one thinks the situation of women is closely analogous to the situation of racial or ethnic minorities, it would seem that that “resistance to stories of social change” should also vitiate feminism in superhero stories. But I agree that in practice it doesn’t.

Of course, maybe the situation of women isn’t closely analogous to the situation of racial or ethnic minorities.

Twilight’s actually a good example of a really weird female superhero narrative too.

I’d agree that Buffy and Sailor Moon and those early Wonder Woman comics too don’t negotiate the complexities of gender perfectly in every possible respect. But that’s true for Pride and Prejudice as well, you know? Or Virginia Woolf, or Octavia Butler, or anything really. Wonder Woman, Buffy, Sailor Moon, Twilight—they’re all works that take female experience and gender difference seriously, and approach those topics in complicated and thoughtful ways. I don’t see them being any weaker in that regard than any other genre — romance, lit fic, horror, whatever.

And Wonder Woman and Twilight do actually reject the idea of violence as world-changing solo action in a lot of ways; they’re both pretty explicitly utopian, and both imagine goodness not in terms of retaining the social order, but of social and spiritual transformation.

There isn’t really superhero genre work about black heroes that do that, as far as I”m aware. As I’ve mentioned before, some of Octavia Butler’s work might qualify. Maybe Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol. Rigamo actually looks very interesting in that regard, but I haven’t read it, unfortunately. I think it’s notable that all the titles I mentioned above (WW, Sailor Moon, Buffy, Twilight) basically occur outside the mainstream (or early enough that the mainstream hadn’t really solidified yet in the case of WW.) If there is ever a black superhero comic that approaches race with nuance or thoughtfulness, it won’t come from Marvel or DC, would be my guess.

Graham, I think there are some analogies, but some differences too. Women really aren’t generally cast as threats to order, for example—at least not in terms of the kind of battlefield set up you get in superhero comics. In fact, women (or at least white women) are often concceptualized as forces for order and civilization (even if a different kind of order and civilization). I think that’s arguably made it easier for them to fit into the tropes of superhero comics in various ways.

Vron Ware’s book Beyond the Pale is just being rereleased, and is a great discussion of the parallels and discontinuities between feminism and racial justice work, if anyone’s interested. Nice new intro by Mikki Kendall, who writes about these issues a lot as well.

this is me testing a comment — sorry for this, but I keep getting bounced with a long comment so i want to see if it’s some weird formatting glitch

@ Noah

You mean outside the mainstream of the genre? (Presumably you don’t mean outside the mainstream of public consciousness, because Twilight must count in that sense.)

The thought occurs that Sailor Moon is maybe an interesting borderline case in that regard: The magical girl genre was established in manga and anime long before it, and flourished after it, but the girl power aspect is, as far as I can find in my sketchy knowledge, pretty anomalous. (Would welcome a correction from anybody reading this who knows more than I do.)

On the other hand, anime had already turned Zorro into a girl in 1975 in La Seine no Hoshi.

If I may: a large part of the disagreement between J. Lamb, one the one hand and pallas and Noah, on the other, appears to hinge on the idea of various kinds of prejudice being inherent to the superhero genre. I suspect that pallas and Noah hear “inherent” the way I do viz. meaning permanent, inseparable, immutable…in which case, pointing to one example (e.g. Adventures of Super Hero Girl) that (putatively) doesn’t have (in this case) sexist prejudice is enough to show that (at least) that particular prejudice isn’t inherent. That’s not a loophole — that’s a counter-example to what I (and, I think, pallas and Noah) hear as your essentialist claim about prejudice and the genre.

Or, a little more schematically, it sounds like you’re saying that, not only are all superhero comics racist and sexist (a universal claim), but any superhero comic MUST be racist and sexist (an essentialist claim, more or less). If there is indeed even one superhero comic that (putatively) isn’t sexist, your claim needs to be weakened at least somewhat — or else, we’ve been hearing it wrong and you mean something weaker all along.

NB: everything I said is compatible with thinking that almost all of superhero comics are, as a matter of fact, racist and sexist, and that we should reject the genre as readers because of this. It’s also compatible with thinking that there are structural features of the genre that very strongly encourage it to be racist and sexist. FTR, I think Noah’s right — the sexism is historically contingent, and even then not universal although predominant, whereas racist tendencies are very strongly encouraged by the standard (pro-vigilante) structure of superhero comics

Graham — oops! Sorry, thought you were more familiar with the comics subculture lingo—”mainstream” in the context of comics means Marvel and DC basically (though maybe occasionally things like Image that try to look exactly like Marvel and DC.) So Twilight isn’t a mainstream superhero title even though of course it’s “mainstream” in the less subcultural sense that it has a huge audience.

@ Noah

Good point re women, order.

I know what The Mainstream is; I (obviously) didn’t realize you were using the word in that sense; thank you for clarifying!

I feel like people keep ignoring the commercialized elephant in the room. Are superheroes not allowed to change the world because of politics/racism, or are superheroes not allowed to change the world because of the need to keep moving units–and a radically altered scientifictional setting makes this more difficult than an illusion of change approach that lets you keep contemporary America as a backdrop?

I suspect that this is a case of commerce’s own dynamics supporting an overall racialist mindset, but I do think that it would be possible to combat the latter with a different approach to the former.

The more J. keeps repeating the notion that the superhero genre needs to be abandoned because of it’s history of racism and sexism, the less and less logical that stance becomes for me. It’d make a lot more sense if this were comparable to the film industry or television or literature having the same problems, but they don’t. As a result, there’s nothing inherent about the genre that can’t be fixed through time and effort. Even the Law and order themes which I agree present problems can be solved eventually through more consistent consideration of the likes we’ve seen in the past from Captain America: TRUTH, Icon (whilst ignoring, or interrogating, the other confused politics of that book) and others. Ignoring the attempts made to engage the genre and the reader with race is equivalent to predicting all remaining problems with race in America will end in a gigantic race war.

I think the argument that J Lamb offers about superhero comics can largely be applied to comics in general (with the exception in some instances of vigilantism, which plays almost no role in ’50s romance comics, for example). That we can and do easily dismiss comics’ largely racist and sexist history as a product of culture or subculture rather than of the format, and that we do so by the same means as others in this thread have used to question J’s contention (that is, by offering counter-examples), I think shows that his argument mostly fails–with the strong and interesting exceptions of vigilantism and collective action.

As to collective action, I can’t think of many good depictions of it in comics in general (although Kindt’s ‘Super Spy’ and certain runs of ‘The Shadow’ focused on the hero’s network of servants come close, and are basically superhero books). Do comics lack the tools to tell a decentralized, grass-roots type of story? Or is it just easier and more marketable to play with or subscribe to ‘great men’ style stories in a climactic format?

As to vigilantism or extra-judicial violence,it is true this generally and quite broadly skews against minorities and the oppressed in real life. Instances of Nat Turner or John Brown styled uprisings almost always end with Nat Turner’s hanging or John Brown’s Body. Getting executed or assinated in a meaningful and permanent death just isn’t compatible with an ongoing, sales driven format.

Separate from most of the above concerns, I have been wondering if perhaps black superheroes might not be more possible or more ‘authentic’ in what I have been thinking of as secret-superhero entertainment. Basically, these are works where at least one character has (or attains) superpowers and may engage in heroic activity, but where the superheroic nature of said action is somehow downplayed (or where the impact or existence of the power is delayed in the narrative) in a way that defies superhero genre conventions. Examples that spring most readily to mind are Paul Pope’s ‘Heavy Liquid’, Hope Larson’s ‘Mercury’, David B’s ‘Incidents in the Night’, and (to switch things up a bit) Adam Sandler’s ‘You Don’t Mess With the Zohan’. None of these deal with race (or, in Sandler’s case, not very thoughtfully), and none of them rely on masks, so whether or not something similar might be done for, with, or by black people, and whether or not it would count as a suphero work is an open question in my mind.

But I wanted to put it to you, because the ‘possibility of a black superhero’ and what that might be, if real, that’s been bumping around my head since the first thread on that here.

@Jones, one of the Jones boys:

I’m saying that I find superhero concept itself hostile to human difference by design. Superhero narratives posit worlds where the characters all act and think and problem solve like straight White men; superhero creators do not allow for the possibility that women, people of color, and/ or LGTBQ folk may approach the use of extra-normal physical and mental abilities differently than Siegel and Shuster’s Superman did in 1938. None of that argues that one creator here or there may not try something different, but when we evaluate material like Buffy or Sailor Moon or early Wonder Woman or Ms. Marvel or Twilight for their feminist contributions, let’s say, I think the best conclusion we’ll reasonably draw is that the record is muddled. Buffy’s not an unqualified feminist success for the superhero genre, by any stretch. Sailor Moon appeals to young girls without being feminist; being saved by or pining over Tuxedo Kamen for large portions of the series rather hurts its adoption of that label.

I believe superhero narratives start with a foundational drive to promote straight White males, even if this promotion only exists in the narratives’ moral perspectives. Race and gender and sexual orientation alter an individual’s notions of identity and justice, but in superhero comics heroes all accept the same ideas about who they are and who they defend, about what evil is and how one best combats said evil. I find this incompatible with the most basic opposition to race and gender and sexual orientation prejudice.

I’m not saying that any given superhero comic MUST be racist and sexist and the like; all superhero comics do not include race or gender difference. Many conceal within their pages post-racial spaces where all humans are straight and White and male, so human difference itself, and the racism, sexism, and homophobia we despise, does not exist. But where superhero comics attempt diversity, I think they display the genre’s hostility to human difference. Women are busty, attractive, and eager for men to display physical prowess to win their affections. Blacks are secondary best friends and jive-talking sidekicks, and/or brooding race men without a full range of human emotions or possibilities. Asians perform martial arts like others walk and breathe.

Many here would like to chalk this genre hostility to human difference up to the fans, or the eras when creators write comics, or to problems with most popular fiction in the West, to expand the blame for fictional prejudice so far and wide that no one need ever feel responsible. This is a mistake.

To make superhero comics more palatable to meaningful diversity, to include substantive human difference into superhero narratives, people have to successfully challenge the superhero concept itself. That concept — the White male power fantasy where a individual White male can change the world to reflect his moral desires through the use of his extra-normal physical and mental privileges — does not allow for meaningful human difference in superhero narratives. For integration to work here creators must discard the logic by which superheroes operate, and once that happens it’s hard to say that you retain what can be classified a superhero. Meaningful diversity, then, breaks the superhero concept, and I suggest that as the explanation for the severe lack of meaningful takes on race, gender, and sexual orientation in superhero media over seventy seven years of trying.

Put another way, John Jennings’ interview above discusses his ‘love/ hate’ relationship with superhero comics, a nuanced, difficult connection to which many blerds could relate. Most mainstream superhero comic fans don’t have such genre/ identity dissonance, and it’s important to recognize why. Superheroes are not for everyone, and those who wish to change this need to grasp the enormity of their project, along with the concept-based opposition they face.

I really don’t think Tuxedo is as central to Sailor Moon as you’re claiming. The emotional energy of that series is mostly about female/female relationships, and friendship as power. Positioning romance as unfeminist is often done, but not convincing, to me.

Buffy’s certainly a mess in a lot of ways. But again, you can criticize the feminism of Pride and Prejudice too. There’s a list of female superheroes that really do not position the heroes as stand ins for white men; Wonder Woman, Twilight, and Sailor Moon. They challenge the narrative directly, which is exactly what you say they should do — basically by, in various ways, rejecting violence and individuality in favor of love and collective action. (Buffy and the Hunger Games are more about saying that the narrative is *not* only for white men, which I’d argue is feminist too,albeit in a somewhat different way.)

Again, the point isn’t that all these comics are perfect. But there’s a pretty solid history of comics which use female characters to question and adapt superhero tropes, not just to rubber stamp them (Promethea would be another, now that I think of it..and Empowered, probably.)

The record on race is a lot dicier.

Thanks J, that clarifies your position. A lot of work, it seems, is being done by this idea:

“For integration to work here creators must discard the logic by which superheroes operate, and once that happens it’s hard to say that you retain what can be classified a superhero. Meaningful diversity, then, breaks the superhero concept”

That’s certainly where we disagree. e.g. Promethea, Gaiman’s Silver Age Miracleman (aka Marvelman), the end of Tom Strong, Doom Patrol, bits of Seven Soldiers, bits of Swamp Thing, bits of Animal Man, lots of Weisinger-era “Superman family”, (the one and only true) Wonder Woman — these all seem to me “to discard superhero logic”, to some extent, but I don’t think they’ve “broken” the superhero concept. If you’ve got a broad enough concept of superhero, it can handle such flexibility. (I think the right approach is a prototype concept, which can contain a whole range of family resemblance).

But if your concept is constrained enough that it can’t cover those examples — if doing that kind of thing with a superhero comic makes it not a superhero comic any more — then, yeah, it’s trivially true that a superhero comic can’t integrate meaningful diversity. But positing that constrained concept as the right one seems rather to beg the question

I was actually thinking about Gaiman’s Miracleman earlier. It’s essentially speculative fiction that happens to feature characters wearing tights for historical reasons. You could say that it’s a model for integrated superheroes where a plotline might involve something nonviolent like Miraclewoman running a dating service instead of people fighting.

Although if you want to do a story about a post-human being running a dating service, I’m not sure why it should be done with characters wearing tights.

So I find it hard to get behind Miracleman as a model for new superheroes, even though it was well done, I don’t see why it should be a superhero story.

oh, I wasn’t trying to say other superhero comics should be more like Neil Gaiman’s Miracleman.

(I wouldn’t say any comics should be more like Neil Gaiman’s anything.)

(j/k — I remember it fondly. I’s been a while but I prefer it in memory to anything else he’s done, including the obvious anything-else)

My point was just: that’s one more example of a superhero comic that doesn’t, prima facie, involve the “White male power fantasy” J. describes. Did it need to involve superheroes? No. Does it actually, however, involve superheroes? Yes. Is it a superhero comic? Yes. Considered purely as aesthetic object, it looks enough like other paradigm cases; and, considered as social construct, it gets classified by various social groups as a superhero comic (e.g. where did it get sold in comic shops? What kinds of best-of or other lists does it appear on?)

I wonder if anyone else recalls the issue of Green Lantern: Mosaic, the one with the “Trendoid” aliens, that explicitly endorsed assimilation. As a member of a despised and marginalized group, I always prefer portrayals of my people that make them out to be diverse and on the whole, on better or worse than any other group – just Americans like all the rest.

The Mosaic, issue, written by Gerard Jones IIRC, has John Stewart arguing that the Michael Jacksons and Vanilla Ices of the world -ridiculous as they may be- are bridge-builders into the popular consciousness, greasing the way to understanding, or at least polite tolerance.

Whether it be racism, sexism, or whatever prejudice at issue, I tend to think highly complex and rather difficult, if not intractable, problems call for nuanced and diverse approaches – sometime you need those radicals over there making themselves obnoxious to put the issue on the table and in front of the mainstream and The Man – but that tends to automatically require more diplomatic and conciliatory voices in the mix to temper the obnoxious, lest the activist become perceived as enemy by a (frankly fickle and gullible) mainstream public. Carrot AND stick, y’know? King AND X.

[shrugs]

I hope everybody has seen the issue – I’m sure I can anticipate a stimulating range of opinions.

First time commenter, (very) long time lurker here. Noah, I want you to know that I find this site A Thing Worth Doing, partly because I don’t always agree, and it’s an education in contemporary progressive thinking, even scholarship, that challenges me and makes me think. I expect there are a lot like me checking by w/o speaking up -this seems a tough room to speak up in casually- and keep up the good work.

Hey BU; thanks so much! I’m glad you took the comments plunge!

I hope I am tomorrow. :D

I would love it if someone (Noah) did a close reading of that Mosaic issue (Noah) and wrote it up – I gather you’re very interested in comics as assimilationist narratives, which speaks to all sorts of the issue often grappled with here, and as the only explicit endorsement I recall in a comic, very worthy of its own article.

I’ll check it out!

Pingback: No, we shouldn’t make X-Men supervillain Magneto black - Quartz

Pingback: Introduction to the #Wakanda Syllabus