“Superman’s powers weren’t unique,” writes Deborah Friedell, “but his schlumpy double identity was,” because “it is the ordinary person, Clark Kent, who is the disguise.”

The assertion is indirectly Brad Ricca’s, whose biography Superboys Friedell was reviewing, but either way, I have to raise my hand from over here in Bath, England where I’m teaching this month, and say, well, actually, no. Jerry Siegel can only claim uniqueness points if you ignore a range of earlier, disguise-reversing characters, including Zorro and the Scarlet Pimpernel–whose 1934 film incarnation Siegel would have watched before his coincidental stroke of Superman inspiration later the same year.

I’m guessing, however, Jerry didn’t read much by Bath’s most beloved literary daughter, Jane Austen. Which is a shame because she penned the first Clark Kent all the way back in 1817. Austen was more or less on her deathbed at the time, which might explain why she was writing about invalids at a beach resort, and, more sadly, why she never finished.

“Jane Austen left few hints about the direction Sanditon would have taken had her health allowed its completion,” writes Austen expert Mary Jane Curry. “Perhaps future study will suggest why, if Austen family lore is true, Jane Austen called it ‘The Brothers.’” Laurel Ann Nattress thinks the middle of the titular brothers, the very good-looking and lively countenanced Sydney, was “possibly to emerge as the hero.” Maria Grazia agrees (“The male hero seems to be in Jane’s intentions, Sidney Parker”), scolding Juliette Shapiro for her treatment of the character and the subsequent romance (“Rather improbable”) in a completion of Austen’s novel.

Shapiro’s is only one of over a half dozen attempts (including a webseries set in California) to pick up where Austen’s dying hand dropped off. Perhaps so many of them fail because they champion the wrong Mr. Parker. My bets are on Sydney’s kid brother, the mild-mannered Arthur.

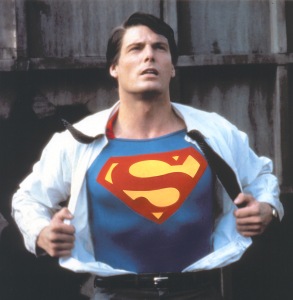

He, like his delicately hypochondriac older sisters, has come to Sanditon to convalesce. Charlotte, Austen’s final protagonist, “had considerable curiosity to see Mr. Arthur Parker; and having fancied him a very puny, delicate-looking young man, materially the smallest of a not very robust family, was astonished to find him quite as tall as his brother and a great deal stouter, broad made and lusty, and with no other look of an invalid than a sodden complexion.” That’s a casting call for Christopher Reeve.

Arthur only receives one scene (more than his feckless brother), but it has all the hallmarks of a Kryptonian slumming as a cowardly weakling. His first line is an apology for hogging the seat by the fire. “We should not have had one at home,” said he, “but the sea air is always damp. I am not afraid of anything so much as damp.” Charlotte is fortunate never to know whether air is damp or dry, as it has always some property that is wholesome and invigorating.

“I like the air too, as well as anybody can,” replies Arthur. “I am very fond of standing at an open window when there is no wind. But, unluckily, a damp air does not like me. It gives me the rheumatism.” He is also, he confesses, “very nervous,” an obscure 19th century condition sadly extinct by the time Siegel was writing, or surely Clark would have suffered it too. “To say the truth, nerves are the worst part of my complaints in my opinion.”

Charlotte recommends exercise. “Oh, I am very fond of exercise myself,” he replies, “and I mean to walk a great deal while I am here, if the weather is temperate. I shall be out every morning before breakfast and take several turns upon the Terrace, and you will often see me at Trafalgar House.” But does Arthur really call a walk to Trafalgar House much exercise? “Not as to mere distance, but the hill is so steep! Walking up that hill, in the middle of the day, would throw me into such a perspiration! You would see me all in a bath by the time I got there! I am very subject to perspiration, and there cannot be a surer sign of nervousness.”

Adding to sweat and humidity, Arthur reveals his most feared form of liquid kryptonite. “What!” said he. “Do you venture upon two dishes of strong green tea in one evening? What nerves you must have! Now, if I were to swallow only one such dish, what do you think its effect would be upon me?” Keep him awake perhaps all night? “Oh, if that were all!” he exclaims. “No. It acts on me like poison and would entirely take away the use of my right side before I had swallowed it five minutes. It sounds almost incredible, but it has happened to me so often that I cannot doubt it. The use of my right side is entirely taken away for several hours!”

Is Arthur duping Charlotte the way Clark dupes Lois? Hard to say. It is clear, however, that the man is masking deeper appetites. Although he pretends, “A large dish of rather weak cocoa every evening agrees with me better than anything,” Charlottes observes the drink “came forth in a very fine, dark-coloured stream,” prompting his sisters’ outrage. “Arthur’s somewhat conscious reply of ‘Tis rather stronger than it should be tonight,’ convinced her that Arthur was by no means so fond of being starved as they could desire or as he felt proper himself.” Arthur has a similar weakness for liberally buttered toast, “seizing an odd moment for adding a great dab just before it went into his mouth.” Wine also does him surprising good. “The more wine I drink—in moderation—the better I am.”

Charlotte, demonstrating the sleuthing skills of a top notch girl reporter, notes “Mr. Arthur Parker’s enjoyments in invalidism,” suspecting “him of adopting that line of life principally for the indulgence of an indolent temper, and to be determined on having no disorders but such as called for warm rooms and good nourishment.” Laurel Ann Nattress (did I mention she has a blog on Austen?) thinks the twenty-year-old has been “cosseted” (presumably by his doting sisters) “into believing himself to be of delicate health.”

That’s the interpretation Bryan Singer adopted for his 2006 Superman Returns. The Man of Steel’s bastard son, the five-year-old Jason, appears to be an asthmatic runt—until he throws a piano at the thug menacing his mother, Lois. Was little Jason just jerking everyone around? Hard to say. But his old man certainly was. The best scene from Quentin Tarantino Kill Bill is David Carradine’s superhero monologue:

“When Superman wakes up in the morning, he’s Superman. His alter ego is Clark Kent. What Kent wears – the glasses, the business suit – that’s the costume Superman wears to blend in with us. Clark Kent is how Superman views us. And what are the characteristics of Clark Kent? He’s weak… he’s unsure of himself… he’s a coward. Clark Kent is Superman’s critique on the whole human race.”

Austen is critiquing us too, our laziness and self-serving foibles, but being also a devoted lover of the marriage plot, would she have left poor Arthur to stew in his rather weak brew of humanity? I’m not suggesting the young man was hiding a capital “S” under his shirt, but Austen seems to have hidden something under there. Lois eventually pulled the glasses off Clark. I suspect Charlotte would have done the same with her tall, broad, and lusty invalid.

An informative piece with a very interesting thesis – so naturally it gets no comments. Well, here’s one. Thank you!

You’re welcome, Graham!

Hmmm. The conventional take I see from where I’m sitting is that Superman is the disguise – though that certainly didn’t appear to be the case at all pre-Crisis.

Yes, it’s amazing how fluid his identity has been over the decades. A third interpretation: he’s Kal-El and both Superman and Clark are disguises.

I wonder what worth there would be in some research into the history of secret identities? Supers seem to owe everything to The Scarlet Pimpernel, but I can’t believe he was first in fiction, being only from 1905…

Chris has a forthcoming book on this very topic: On the Origin of Superheroes.

@ BU

Well, I can at least think of one other example from 1905: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Clansman

Yep; Chris talks about the KKK as superhero progenitor on this site, and in his book.

Thanks, Noah. And yes, BU, the earliest dual-identity characters I can find are Nick of the Woods in the U.S. and Spring-Heeled Jack in England. Though single-identity superhumans go even further back. As far as most influential though, Graham, the KKK may be the biggest in the two decades leading up to Action Comics.

Of course, in a way, there’s Jesus. (In Mark, he even repeatedly tells his apostles not to reveal his true identity!)

And other stories about gods and other supernatural entities disguised as people.

Yes, Jesus is Clark, and Christ (literally “the Messiah”) is Superman. He has superpowers, a mission, and an identity-reflecting icon. And an arch-nemesis too.

Ha! Yes, Satan is a great supervillain! (Including how fate has decreed that he can never actually win, poor guy.)

I did read Chris’ recent articles here on the subject, and I ain’t too bright sometimes.

But I’d assert that entirely to much could be made of the Klan stuff to be found among the real roots of the genre – I’ve never seen a compelling argument that it was actually inspirational by an order of magnitude like the Pimpernel assuredly was.

@ BU

You need a compelling argument for the influence of Birth of a Nation on, well, everything?

Anyway, if this is a question of establishing the superhero genre’s innocence of morally reprehensible influences, then let’s note that a novel about saving the poor, unjustly persecuted French aristocracy – except for a few bad apples, of course! – from the Revolution, as travestied by Thomas Carlyle by way of Charles Dickens, isn’t exactly an honorable ancestor either.

Nice article! I do think that it is Clark who is the true identity, though I definitely would not disagree that Jerry was stealing from tons of secret ID heroes and bad guys, as well as dual roles in his own personal life. Looking forward to your book, Chris!

The Klan is an interesting angle, too — Jerry definitely knew about them and hated them — he wrote an early comic story about actual Klan activities in Meadville that was not without risk to publish. I always thought the Baldknobbers had a little Batman in them, but it’s mostly speculative:

http://www.comicsbeat.com/unassuming-barber-shop-batman-country-part-one/

I would say Superman is the true identity and Clark the costume, for the reason that it’s certainly that way in the Christopher Reeve movies, and they (especially the first) have become for most people the definitive version of Superman. (Though somehow everybody still knows Lex Luthor is bald and serious, and not Gene Hackman with a toupée on his head and a smirk on his face.)

And, come to think of it, everybody somehow knows that Lois Lane is cooler than Margot Kidder.

Or Amy Adams (dear God).

Thanks, Brad! I didn’t realize it was already up for pre-order on Amazon until Noah linked to it. And as far as balknobbers, yes, I’ve wondered that too, but haven’t dropped down that research hole yet. And Superman is sort of an anti-Clansmen who, paradoxically, contains Klan-like (or at least general violent vigilante) elements.

And, Graham, Lois will always be Terri Hatcher for me.

All honor to Terri Hatcher, but to me she’ll always be Dana Delany.

Hmmm. The Klan is of no interest to me, and I guess I’m only pointing out that to ignore that presence in the genre roots is to tell a lie of omission, but that to bring it up too casually can be another kind of lie, what with mentioning the Klan being a virtual godwinning of the topic (as Alan Moore had the Nova Express editor do deliberately in Watchmen back-pages text).

The truth of the matter, I think, is that the commonalities between the heroes of Birth of a Nation and Supers in our modern escapist graphic entertainment don’t include much of the first thing people associate with the Klan. I can think of a number of “Hangman”-themed characters, but no racist “heroes”.

Comics’ sins on race tend to resemble lies of omission far more than lies of commission…

Okay, as soon as I posted, I realized that I’d went and mentioned Watchmen and not dealt with Hooded Justice, a deliberate evocation of Hangman and Klan themes w/ hints of actual racism, and Captain Metropolis displaying an offensive sensibility in that chart at the Crimebusters meeting – not sure they count, as Moore was doing it on purpose to court our discomfort…

But when you read The Clansmen (or watch Birth of a Nation), the characters don’t understand themselves to be racist and, perhaps more importantly, the audience did not understand them to be racists either. Within in its cultural context, the KKK really were “heroes.” Contemporary heroes share none (or very little) of the KKK’s racist attitudes because of the overall cultural shift, but the formula, masked vigilantism employed for the greater good, is essentially the same. It’s just that the accepted definition of “greater good” has thankfully changed.

That’s why I didn’t scare-quote when I called the Klansmen of the movie the heroes…

Secret identities have been around since the dawn of human storytelling. Gods such as Odin, Heimdall or Hermes would walk the earth in human guise, often to set up tests of morality among us mortals. Shapeshifters — tales of werewolves (Europe) or fox-witches (China), wounded in the paw, only to be found out when their seemingly innocuous human counterparts sport maimed hands…

Then there are the sovereigns who would disguise themselves as commoners to walk the streets incognito, most famously Caliph Haroun Al-Rashid in the Thousand and One Nights, or the Duke of Vienna in Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure. There were real kings who used to do this, too, such as Louis XIV of France.

As for the psychological masking — “Clark Kenting”– evoked in Chris’s article, that’s an old tactic of legend and story. The Roman Brutus feigned idiocy to escape the notice of tyrannical king Tarquin the Superb –‘Brutus’ is Latin for ‘stupid’. Then Brutus led the revolution that overthrew Tarquin and established the Roman Republic.In an identical vein Amleth, Prince of Denmark, feigned idiocy in order to deceive his murderous uncle Fengon whom he later snuffed. The 19th century play Lorenzaccio introduces the theme of the fat-headed, decadent fop who is secretly heroic, decades before The Scarlet Pimpernel.

Clark Kenting continues today in everyday life. The subordinate who masks his intelligence so as not to overshadow his boss, the malingerer, etc…

Alex, have you read the sections of Ovid with werewolves? You also make me think of Odysseus, how he pretends to be crazy to avoid the Trojan War draft, as well as later when he becomes “Nobody.” And I wish I knew about Lorenzaccio when writing my book!

More Odysseus and Odyssey: Odysseus pretends to be — and must (temporarily) accept the mistreatment of — a beggar before the ruff-tuff suitors. But of course that’s just one of many personae that he adopts to fool, e.g., the swineherd, his father, and as you note, the cyclops. Athena also adopts many “downgraded” disguises to advance her plans: she poses as a traveling stranger, Mentor, a little girl, etc.

Well, Odysseus is identified from the start as “the man of many wiles”. Assumed identities are a traditional weapon of all tricksters, no?

Absolutely, Alex! Just noting how much that secret-ID trope (disguising yourself as lesser, as “normal”) is present throughout. Odysseus is, indeed, celebrated as having the power of twists/turns/changes/tropes — a human version many other superhuman transformers in the epic (Athena, Proteus, Circe).

“Clark Kenting continues today in everyday life. The subordinate who masks his intelligence so as not to overshadow his boss”

Grant Morrison I think would suggest Clark Kent is the incompetent boob who “imagines” that he’s awesome and super and will get the girl who is too good for him. Superman is Clark’s fantasy of being great. Clark is his real life, Superman is his daydream.