The index to the entire Joss Whedon roundtable is here.

_________

Spoiler, but not a big one: Age Of Ultron’s last big action sequence ends with our heroes shooting down drones. Iron Man 3 and Captain America 2 both having ended the same way was kind of a giveaway. Marvel’s last few movies have had an surprising topicality, and this last one is no exception. But Winter Soldier got all the accolades for coming out against the surveillance state while thinkpieces on Ultron were comparatively few.

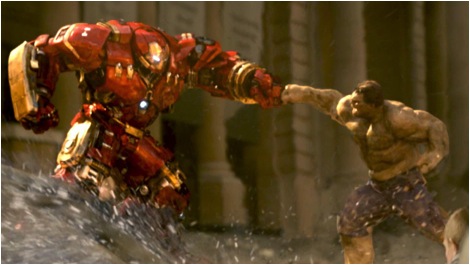

From both his recent declarations since leaving Marvel and from cursory knowledge of Hollywood, you know that doing Avengers 2 came with a few constraints. One of them was that it had to be bigger than the first one. So instead of New York, this time the whole world is the stage. This, and the growing concern over destruction porn following movies like the first Avengers and the Superman reboot, means that Avengers 2 is surprisingly filled with things like characters concerned with property damage and getting civilian victims out of the way. A subplot mandated by the future Black panther movie also gives us a passage about exploiting foreign countries’ natural resources.

We end up with would be world saviors building killer drones, taking metal from Africa to build super weapons in Asia, plus some resentful American bombings victims in Eastern Europe. Topical! Avengers 2 is a movie about America and its relationship to the world. (note the careful avoidance of the Middle East: Whedon probably knew no big budget movie from Hollywood could treat the region in a tone other than jingoistic). It all gets muddled in the necessities of having ten previous films to follow and just as many sequels to set up, but it’s probably the most explicitly relevant blockbusters of the year, and one of the few overt political statements in Whedon’s oeuvre.

Joss Whedon studied at Wesleyan under Richard Slotkin, who wrote about the myth of the American frontier in books like Regeneration through Violence. In his writing, Whedon hascertainly portrayed more than his share of Americans self actualizing through high-kicks, lasergun shots and mythical hammer blows. As a liberal he seems to struggle with this violence, though. So in Avengers 1 you get super heroes stopping SHIELD from atom bombing New York, and the organisation is purely and simply dismantled in Winter Soldier (Whedon had a nebulous role as supervising writer on all Marvel movies at the time, so I choose to consider “larger events” in these movies as at least partly his doing).

But how do you escape the violent trapping of the American myth? You can’t, Whedon seems to say. Certainly not in big blockbuster about a bunch of super strong guys. So the moral from Avengers 2 may then be “admit you failed and try again”. It’s what Tony Stark does when he builds Vision to save the world after failing to do so with Ultron, and it’s what SHIELD does when it comes back as a big warzone savior in Age Of Ultron. In the end, SHIELD has new soldiers and new Avengers to hit the bad guys with but it’s going to be different this time because they really really mean it.

Firefly is Whedon’s other big political statement. It tells the story of a bunch of rogue space cowboys, in a corner of space far from our own, where humans have had to settle after the destruction of Earth. The protagonists are on the run from the Alliance, a central interplanetary government that emerged from a civil war our heroes were on the losing side of. One of the things Whedon stressed in interviews at the time of the series was that the Alliance was essentially benign (they do end up looking bad in the movie, how much of it was a change of mind on Whedon’s part I don’t know). Our heroes were then rebelling against… what? Organised government? Bureaucracy? The loss of a certain sense of adventure?

The later one seems more likely. Joss Whedon likes comfortable modern life, but he also loves romantic stories of demons and super heroes, living on the frontier, rejuvenating through violence. His Angel is a metaphor for fighting addiction, but on a surface level it’s the story of a knight who cannot stop fighting, again and again, and I’m not convinced the metaphorical level is more important to Whedon than cool swordfights are.

Buffy, for all its reputation as a feminist show, was only so because its protagonist was female. She rarely, if ever, is confronted with outright misogyny. Occasionally she fights a phallic giant snake, but they just as often she battles standing metaphors for various non-gendered teenage fears. She fought a stupid military built demon cyborg that stood for god knows what. She also fought evil itself. Buffy was not so much about fighting patriarchy as she was about fighting for fighting’s sake.

Whedon’s adoption of combat as a value in itself is symptomatic of a post ideological left. You can identify big, systematic problems like America’s capitalistic and military dominance of the world, or patriarchy, or bureaucracy, but you don’t have any big, systematic answer for them like Marxism once provided. All that remains is the will to fight, and the hope of punching the bad guys away (metaphorically). So you tell yourself stories of people who keep punching, no matter what.

This isn’t a beef specific to Whedon (I dislike many other things!) but since Dark Knight the thing you’re describing here has been the tendency among practically all action franchise films, there’s some kind of half-examined “political relevance” shoved into these movies which is really just a kind of unconsidered label for simple “evil.” As you note here, Whedon has being doing this since before it dominated the entire genre, A:R takes a series that spent 3 movies building Weyland-Yutani into military industrialists and makes “mad scientists” the villains. But I think Whedon understands superheroes pretty well, which is why he doesn’t really try to engage that at all. Umberto Eco and later Richard Reynolds noted that superheroes can only ever really return things to the way they were before something bad happened (which is why Mark Millar’s Authority is so fun/terrifying, they become proactive), but engaging a specific political belief runs the risk of narrowing the audience. The least successful recent James Bond movie, Quantum of Solace (which I like a lot actually) takes a very progressive stance making its villain essentially an analog for the CEO of Nestle, which is bizarre for a character who stands basically entirely for British Empirical masculinity; things were set right once again in Skyfall as the villain returned to being a physically deformed vaguely homosexual foreigner representing a threat to England’s integrity. Apparently this is important even if they audience are Nazis, as HYDRA goes from science-nazis to ideology-less terrorists from Cap 1 to Cap 2. Whedon plays this a little smarter by just making it personal. What does Loki want? To enslave humanity. Why? Uh…his feelings are hurt? What does Ultron want? same answers.

Pretty fair criticisms of Whedon, especially the Avengers. Angel pretty clearly states several times that there’s no real end game except continuing to fight the good fight. It literally ends on that note. Buffy seems to try to take a different route. And the more I think about the finale the more I like it. They literally empower (some) women in order to try to end the fight. Firefly, I just kind of ignore the comparisons to US history and enjoy it.

Thinking about his work as a whole, I think there’s something to be said about the medium he’s working in and the state of the project in relation to its potential cancelation. When he can dictate the ending he’ll try to at least somewhat end the fighting: Serenity and Buffy. When he can’t dictate it he’ll opt for the “keep fighting the good fight”: Avengers and Angel.

I feel Nolan’s movies have less trouble reconciliating Bruce Wayne’s dedication to punching with their randian ideology.

As for your theory David, it’s interesting to compare those series “keep on fighting” ending with movies Tim talked about in his piece: Cabin in The Woods and Alien Resurection (If my distant memory is to be trusted) both ended with world destruction. Serenity may also be interpreted has ending in intergalactic political chaos (although my assesment would be that, in the end, Alliance citizens wouldn’t care that much about genocide).

And even if Buffy the one thing he ended on a kind of victory, all of Sunnydale is destroyed. So in the end, either you keep on fighting, or you destroy everything and (maybe) start again with a new frontier to conquer.

“Whedon’s adoption of combat as a value in itself is symptomatic of a post ideological left.”

I think it’s as much a symptom of how popular entertainment, television and film, heroic narratives, and mainstream production result in an emphasis on conflict and spectacle. When all three are combined, punching tends to take primacy. It may be what comes across even for authors more intentional about ideology than Whedon. The baby carriage on the steps is what has permeated culture from Potemkin more than the systemic Marxist answer.

I reference Eisenstein in part because his career is about compromise vs. art/political integrity. The reductive version I got in film school was he kissed Stalin’s ass to keep working, yet managed to make art within those constraints. [He also experienced the cycle of critical praise then backlash.]

I would argue compromise has marked Whedon’s career. He seems eager to finish projects even as he expresses displeasure at financial/artistic/ideological limitations. He and his fans both discuss finding the moments of artistic/emotional integrity in work limited by other circumstances.

As Whedon incorporates insider concerns into his storytelling, compromise is also a recurring theme. The final season of Angel was about trying to use evil’s tools to do good then the merits of fighting despite certain failure.

Because such a present concern, I’d argue compromise is a stronger theme and issue than others in Whedon’s work. In terms of ensemble stories and characters, it’s useful. In terms of ideology it can be weak, incoherent or frustrating.

I think, however, part of the problem is Whedon’s public persona, which is not entirely his own doing, is more uncompromising than his work has ever been. And this dissonance between the image of Whedon the strong feminist/leftist auteur and Whedon the canny showrunner who has managed to be more overtly non-misogynist can be infuriating.

After posting the above, I realize “combat as a value in itself” may also be a problem of what functions as a personal theme can fail as ideology. “Keep fighting” is a great metaphor in the abstract for individuals feeling discouraged personally or politically, but when conveyed via actual images of punching or about people caught in actual fights, it reads very differently.

It’s worth bearing in mind that this kind of ideological washy washiness didn’t start recently, nor even with classic Hollywood and comic books: It’s been a feature of popular entertainment ever since the French Revolution (e.g. Dickens, where the solution to mean rich people is nice rich people, and when the poor stand up for themselves in A Tale of Two Cities, they’re supposed to be at least as bad as their oppressors; also the premise of at least half of all Italian and French operas).

I’ve never see a workable statement of theme articulated for Angel before, so big congratulations for that keen insight. The show had a complete oil change of cast during its run, save the star (who, like Buffy, I found the least interesting element of his own show, and to a far, far greater degree) and always appeared to me to be flailing around for its entire run looking for an identity. Serious thumbs up for putting your finger on something real and important there, Cédric – I may get a lot more out of the show on a future watching.

I do have to wonder, though, as you do, how much of it was intentional. I always said of Xena: Warrior Princess, a show that was clearly about growing up -a bad person trying to be good and do what’s right instead of what’s easy (thank you, Dwayne McDuffie)- that I suspected that thematic unity was something of an accident, given the generally slap-happy quality of the writing.