I had somehow missed The Silence of the Lambs, viewing it only a few years ago, well into my adulthood. After years of making jokes about how “it rubs the lotion on its skin,” my husband got frustrated with my blank looks of incomprehension and queued it up on Netflix. As Buffalo Bill grows increasingly irate with his captive, screaming at her “or else it gets the hose again!”, I burst into tears. A 30 year old woman frantically crying over an often-mocked scene in a 20 year old film.

My husband was unnerved to say the least—he had seen the film when it came out, and since it circulated in popular culture in a recognizable way for him, the line had lost its teeth. It was cheesy, and morphed into a joke. I, on the other hand, had no context for the line, and had heard it for years as a cutesy phrase that referenced a film I’d never watched. Having it replaced in its proper milieu was jarring. Instead of a tacky scene worthy of ridicule, something about the pronoun—“it”—and the directive about lotion reached around the rational part of my mind and struck me directly in the amygdala.

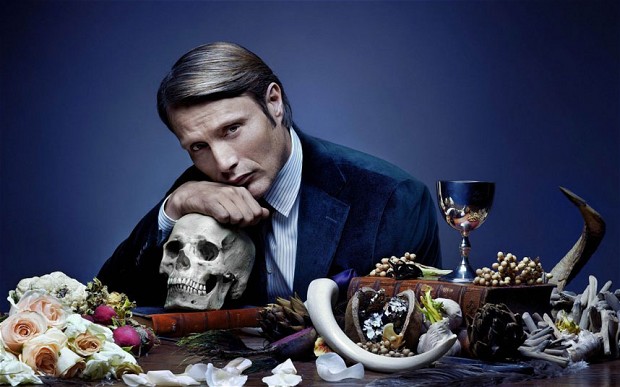

I unintentionally overlooked the television series Hannibal until two seasons in, when I was looking to kick off last summer with some horror. The glorious cinematography, the powerfully reserved acting, and the beautifully rendered script combined to make a stunning and tense dance of intellect and gore.

The first and second seasons are fixated on the strain between knowledge and ignorance. Will Graham, a special investigator for the FBI, is capable—according to Dr. Lecter—of “pure empathy”; he can mentally reconstruct a murderer’s actions, playing the role of the criminal in his internal recreation of the drama. Special Agent Jack Crawford contacts Will to assist him on a case in which young women of the same physical description have been disappearing. Crawford’s initial role is less that of a capable investigator than a pushy delegator. Dr. Alana Bloom, a purportedly intelligent psychiatrist, has taken an interest in Will, and wants to protect him from what she sees as Crawford’s potentially disruptive pressure. To this end, she introduces Crawford to Dr. Hannibal Lecter, who is tasked with monitoring Will.

The show relies on the audience’s pre-existing knowledge of Dr. Lecter operating in the background. Assuming we have seen the unhinged Anthony Hopkins biting the cheek off of a prison guard and recounting eating a liver with “some fava beans and a nice Chianti,” we are faced instead with an eminently rational and restrained Lecter in the show.

Lecter’s self-possessed mien in Hannibal stands in stark contrast to Hopkins’ portrayal, and while the audience knows he is the “bad guy,” the show operates less on the shock value of the murders under investigation or Lecter’s own gastronomical vagaries, and more on how power and knowledge must be—as Michel Foucault insisted—thought together.

Foucault equated knowledge with power, something that those currently struggling under the auspices of austerity in the academe may find laughable, but it’s an equation that is nonetheless compelling for situating current debates about the role of those with knowledge, and what types of knowledge can (or should) be leveraged into power. In Hannibal, Lecter uses his intellect, as well as his privileged status as confidant and guide for Will, to conduct increasingly bizarre experiments on him while the latter is in a fugue state. Lecter manipulates those around him, relentlessly curious about the boundaries of goodness and empathy in those who have the capacity for them.

Foucault is careful to distinguish between knowledge that is laden with power and knowledge that is marginalized. He specifically notes the “disqualified knowledges” of the mentally ill, but broadens this to say that “We are concerned, rather, with the insurrection of knowledges that are opposed primarily not to the contents, methods, or concepts of science, but to the effects of the centralizing powers which are linked to the institution and functioning” of a discipline (Power/Knowledge 84). In regards to this, he parses the way in which power is only thought of as something that is exerted, rather than something that is naturalized and replicated without direct activity.

As shorthand, it can be thought of as the distinction between the power of having and the power of doing.

Hannibal’s ability to unnerve and disquiet rests not on the “reveal,” as with many crime thrillers. The audience already knows who the villain is, even as the team tries to sort out other cases of varying drama and terror. Instead, the appeal of Hannibal rests almost entirely with the tacit knowledge shared by the audience and Lecter: that he is the antagonist, but we still want to see precisely what he is capable of in relationships. In fact, the least interesting scenes in the show are those that depict him enjoying a meal of a person alone. The tension instead resides in watching Lecter use the knowledge he has of himself—as well as his developing theories about other characters—to his own ends.

I’ve been reflecting on Hannibal throughout the year because its peculiar blend of refinement, psychopathology, and epicureanism holds me in a strange thrall. It reminds me of other debates about power, both the having and the doing, because the show has crafted a world in which the rules of behavior and the exercise of power are nearly illegible to those in the best position to address the atrocities occurring within their midst.

In particular, as I watch the third (and possibly final) season of Hannibal, I’m also embroiled in the ongoing debate about campus sexual harassment, launched in part by Laura Kipnis in her now-famous Chronicle of Higher Education article “Sexual Paranoia Strikes the Academe.” This may seem an odd pairing—a show about a psychiatrist/cannibalistic serial killer and a turgid debate about whether or not professors should be permitted to have sex with students—but I can’t help but think that the same questions about power are at stake.

For those who haven’t followed the discussion, Kipnis’s argument rests on three major elements. The first is that administrators are overstepping their boundaries and are infringing on academic freedom. This is patently true, and doesn’t merit debate. Administrative overreach has been consistently critiqued over the past 30 years, and is getting worse as faculty are increasingly shifted to the status of contingent labor. Furthermore, because of this administrative overreach, it is increasingly clear that non-educators are determining educational policy, always to the detriment of students’ actual development.

Second, she contends that an obvious example of this is new policies prohibiting professor-student romantic relationships. These policies have been implemented at a variety of universities to quell the tide of demonstrations against campus sexual assault. While I personally agree with these policies, I can see the potential problems with them, and am willing to debate them.

Third, she argues that the supposed “sexual panic” on campuses is vastly overinflating a relatively benign problem, and that students’ own sense of exaggerated vulnerability is actually making professors the more vulnerable class. This is ridiculous. Professor-on-student sexual harassment and assault are still significant issues. While student-on-student sexual harassment accounts for 80% of reports on campus, that still leaves a sizable problem. Furthermore, many cases of both varieties go unreported. For example, Kipnis asserts that

For the record, I strongly believe that bona fide harassers should be chemically castrated, stripped of their property, and hung up by their thumbs in the nearest public square. Let no one think I’m soft on harassment. But I also believe that the myths and fantasies about power perpetuated in these new codes are leaving our students disabled when it comes to the ordinary interpersonal tangles and erotic confusions that pretty much everyone has to deal with at some point in life, because that’s simply part of the human condition.

Here, she is conflating normal misunderstandings with harassment.

My annoyance with the tenor of this discussion has increased with the tone-deafness of Kipnis’ understanding of power and its subtle manifestations.

In Hannibal, the audience is in reluctant collusion with Lecter as he manipulates and slaughters characters. There are—of course—the “ordinary interpersonal entanglements” of daily life. Will Graham and Alanna Bloom share an attraction, but because Alanna is concerned about Will’s mental state, she refuses to enter into a relationship with him. Jack Crawford’s pressure on Will to use his empathy can grow harsh. However, standing in stark contrast to these relatively benign interactions is the maneuvering of Lecter.

Interestingly, both Will and Lecter work from the point of curiosity about human emotions and motivation. While Will is able to adopt the perspective of others who have committed misdeeds in the past, Lecter is able to use his observations to predict future behavior. Both are talented, but only one begins the series with a sense of the way in which his knowledge brings him power. In the first season, Lecter experiments on Will after discovering that he has the symptoms of encephaly. Instead of seeking surgical treatment for his patient, Lecter devises a series of experiments in the clinical setting to encourage Will to lose time. In entrusting his mind to another, Will is violated at both the psychological and bodily levels because he fails to discern how this power can be leveraged against him.

After Will reconstructs a crime scene that includes a grisly totem pole of bodies, he loses time and appears at Lecter’s office door. Lecter tells him that this is the result of his psyche “enduring repeated abuse,” and Will frantically objects that “No, NO! I am NOT abused!” Lecter repeats that Will has an empathy disorder, and that disregarding his disordered psyche is “the abuse I’m referring to.” Here, abuse is relocated as being the act of the person suffering—abuse at his own hand—rather than being visited from the outside. This recalls Kipnis’s argument that it is students’ sense of vulnerability, rather than objective conditions in which they are disempowered, that is the problem.

Will wants to find a physical—objective—cause for his disorder. The viewer already knows that Lecter is hiding some aspect of this from Will, but it is not until the following episode that we see there is indeed a physical cause for Will’s rapidly fraying sanity, a cause that Lecter pressures the neurologist to conceal. Much like the objective problem of sexism within the academe, Will’s disordered brain matter has psychological effects that are erroneously attributed to more ethereal causes.

It is not that Will or Lecter stand in an easy allegorical relationship to students and professors in relation to Kipnis’s argument. Instead, Will and Lecter represent two distinct modes of knowledge, both of which are necessary to understand the real causes, circumstances, and consequences of sexual harassment in the academy and elsewhere. Lecter has power in his superior knowledge of the mind, and is not afraid to leverage it to his own ends. In this sense, we must remember that knowledge is not equivalent to ethics.

Will, on the other hand, has the capacity to understand others on an experiential level—to feel as they feel—but this very gift is also potentially disabling. Neither emotion nor reason are able to wholly grasp the diegetic world of Hannibal. Instead, there is a third term—power, and its subtle operation—with which all of the characters in both the on-screen and real-world dramas must contend.

It would be foolish, however, to equate Lecter’s power with his capacity to do violence on others. Violence is almost beside the point of the show, much like violence is frequently beside the point in terms of sexual violence. It remains popular to say that “rape isn’t about sex. It’s about power.” However, too often, those who remark on this conflate power with violence, as if violence is the only way in which power operates. Power in the world of Hannibal is not Lecter’s murders, or the murders by other various and sundry psychopaths populating the chorus of the show. It is the leveraging of psychological force.

One of the greatest myths that persists to today is that sexual harassment, and sexual violence, are invariably violent in the traditional sense of the word. The ham-handed training on sexual harassment provided by private companies making money off of universities trying to comply with Title IX do little to help this issue, as they have themselves a vested interest in concealing how subtly power circulates in a workplace, classroom, or clinic.

Perhaps this is less than legible for those who have acclimated themselves to shows of force. For example, Mads Mikkelsen, the actor who plays Lecter in Hannibal, was recently featured in Rihanna’s new video “Bitch Better Have My Money.” The video represents Rihanna as a kingpin of some sort whose accountant, Mikkelsen, has stolen her money. She kidnaps and tortures his wife, which doesn’t particularly phase him, so she goes on to torture him.

The video is an interesting contrast to Mikkelsen’s role on Hannibal. While he is still situated in relatively luxurious surroundings, he is ultimately at the whims of Rihanna. Furthermore, some critics have levelled the charge that the video is misogynistic because of the violence she visits on the woman who plays the wife of Mikkelsen. Speculations flew about whether or not this was a revenge fantasy about Rihanna’s real-life former accountant. Feminists of color have (rightly) pointed out that white feminism hasn’t always been welcoming to women of color.

Even the debates surrounding this video illustrate how fraught power is, particularly in relation to those who have been historically oppressed. Of course, the theft of money and sexual harassment or assault are not equivalent. Instead, this clearly illustrates how the public tends to react to obvious displays of violence—particularly from a disadvantaged woman, and in this case, particularly a woman of color—versus its critical acclaim of a white man with an advanced degree who eats people.

Hannibal is more than a show about a dude with “refined tastes,” however. It’s a series that best hits its stride when the audience is gazing on the beautifully plated delectables we know for a fact are composed predominantly of the minor character killed off in the previous scene. It’s a series that does more with an eyebrow raise, a small hand gesture, or a mild remark, than most shows are capable of doing with an ample explosives budget.

And it is loved—and found disturbing—precisely because we recognize that the power wielded by Lecter is at its most insidious when it is least obvious.

Obvious displays of power are few and far between. It would be delightful if tomorrow I could wake up in a world where power had shifted so far from the hands of professors and administrators that students weren’t threatened in a variety of ways by their moods and their decisions. Lecter remarks late in the second season that “Whenever feasible, one should always try to eat the rude,” but even at this point, Lecter still knows much that Will does not.

After all, Hannibal kills both for pleasure and for necessity. He only eats those he considers equivalent to the animals most humans ingest. As he remarks to a character he’s keeping captive, “This isn’t cannibalism, Abel. It’s only cannibalism if we’re equals.”

And so goes Kipnis’ argument. It is only sexual harassment if we pretend that we are equals, and that there are not small, subtle (or even obvious) power dynamics at play. It’s only violence if it looks like it to her.

Power isn’t merely in the exercise thereof. It is in the ability to assess whether or not it was exercised.

For this being mostly about a TV show I haven’t seen, I do really appreciate this piece. The idea that feeling persecuted is a form of oppression is so incredibly pervasive, and should be called out, with Kipnis and with all these other aggrieved faculty. The students can be irritating, but they are not the enemy.

I liked the discussion of violence, and how abuse of power is often reduced to violence and nothing else. I think this overlaps with some of the free speech discussions we’ve had here. In the U.S., speech can generally only be restricted if it is a direct threat of harm, i.e. violence. Discussions of free speech then tend to assume that speech can’t be an abuse of power, or a danger, unless it leads fairly directly to physical violence.

Well, in the case of Peter Ludlow the principle of free speech seems to overrule the possibility of violence. Like, does anyone think that blackmail isn’t violent? If someone has the power to affect your career and they demand something from you as (explicit or implicit) payment, that’s blackmail.

It’s also interesting (as is the Rihanna thing) alongside the new story about the Runaways manager raping members of the band- I’m seeing enlghtened artsy types implying that it’s some kind of setup (and therefore Bill Cosby by extension).

(BTW, Peter Ludlow is the professor under discussion in the Kipnis articles)

People are defending Kim Fowley? Seriously? I guess nostalgia will make you defend anyone, but for pity’s sake…

Off-topic to the post, over which I’m still ruminating, but Currie and Jett both stated they definitely would have intervened if it was true; which is troubling.

An old friend of mine used to argue that rape revenge movies were dangerous because they gave a fantastic view of feminine agency, making very unlikely reactions seem natural, easy, or even the standard of response or “strength.” He argued this for Hard Candy, specifically — A little girl taking on a serial predator. Right.

Considering the Feminist stakes for Jett in particular makes me think back to this analysis. Currie actually said she’d have broken a chair over him. Good for her if so, but not very likely, ime, unfortunately.

Thanks for the discussion! @Bert, just as a recommendation, it really is a brilliant show. I’m invested in it well beyond its provision of a lens for the Kipnis discussion, but I thought it was a smart, nuanced piece that mapped in a cool way onto that and other debates about power and who holds it, as well as that misplacement of the sense of being under siege. Noah’s exactly right too in his condensation–the idea that free speech exonerates the bearer from accusations of misused power.

In terms of the Rihanna video, I loved it from the beginning, but once I was reminded of the scandal with her accountant, it grew more fascinating as a way to think about how power flows back and forth.

Nix 66, I’m very much inclined to agree with that interpretation of rape revenge movies, and it actually neatly dovetails with what I was trying to get at–while not all women (or men) have experienced such a power play, it’s considerably more difficult to assert any kind of real agency in those moments than Kipnis allows for.

Nix, that makes sense. One of the things I like about I Spit on Your Grave is that I think it presents the revenge as being enabled mostly because the guys in question are so sexist they basically let her kill them even after she says, “if you let me, I will kill you.” Also, the revenge destroys her (or at least, that’s my reading.) It’s not really a feel good film about power and agency, which I appreciate about it.

**Noah: Yes. Most rape revenge movies are utterly horrific in their effects. I agree. No one triumphs. And yet there is this fantasy of agency in it, despite the foreclosure of a future anyone could consider worth living.

Another film, “The War Zone,” is a very brutal film about the effects of an incestuous father on an entire family. It ends as best it can to my mind, with the confrontation and murder of the father. And yet there is not one lick of triumph in any of that. No redemption. Nothing. It’s utterly devastating. I appreciate the film specifically because of how terribly uncomfortable it is for me from a pragmatic standpoint. On the one hand: The father is confronted and taken out. He was not allowed to continue. That almost never happens. On the other: How the hell are the survivors actually supposed to survive the act of murder, and patricide at that? Answer: You don’t.

**Kate: I really enjoyed this piece, particularly this line: “Power in the world of Hannibal is not Lecter’s murders, or the murders by other various and sundry psychopaths populating the chorus of the show. It is the leveraging of psychological force.”

I find that quite just and I think it does shed light on Kipnis’ capacity for free speech, which seems so total that it drowns out the reason why the grad students filed the Title IX complaint against her in the first place. The students can’t seem to make themselves understood, and no matter what action they take they seem to be criticized for having chosen the “wrong” act, as if there is a plethora of ways to deal with this sort of thing and they should are being tested in their choice. It actually seems to me like they’re criticized for not having had sufficient power.

I also find it really interesting that Kipnis is never questioned about what she means when she says she’s a feminist, whereas BBHMM was seen by some as misogynistic/not-feminist.

This may be a stupid/too broad question, and I’ve only watched “Hannibal” up until Hannibal hides Will’s disease from him (I think that’s season 2?), but here goes: Do you see any benefit/possibility for agency to Will’s empathy? Or is his knowledge strictly “disqualified knowledge”? Is it that he feels others which disqualifies him, because his subjecthood isn’t sufficiently stable?

I’m reaching a bit far back up up the comment thread, but on the note of rape revenge movies, I recently watched Maleficent (not very good, in my opinion) and I was informed by a friend of mine that the writers (minor spoilers ahead) of the movie meant for early events to stand in for rape. Stripped down to the key events, Maleficent is a benign forest protector (a sort of Earth Mother) who is in love with an ambitious peasant who betrays her and cuts off her wings. That violation is supposed to stand in for rape, and motivates the actions that drive the rest of the movie. After those events, Maleficent becomes “evil” and starts using her powers (that she supposedly had before but did not exhibit) to take over the forest and curse Aurora, the baby princess. After all that, Maleficent is shown to have enormous power, and uses it almost exclusively to hurt and toy with people. And she is the only female character who remotely has any agency (the crux of the movie is that she alters the destiny of another female character, taking away her agency quite explicitly). In fact, the only time Maleficent ever uses her powers for life-affirming action (when she tries to lift the curse from Aurora to save her life) she is foiled by her own earlier, destructive power. Long-winded lead-up aside, Maleficent seems to say that women can ONLY ever exercise power after they are victimized, as if victimization (of the female agent) is a necessity for female agency. That sentiment seems to be echoed by Rihanna’s video, and the whole concept of rape-revenge. In fact, it’s hard to find a popular heroine who wasn’t priorly victimized: Furiosa lost an arm (and was sex-trafficked?), Black Widow was brainwashed and castrated, Bella was in a horribly dangerous and abusive relationship, and Anastasia in Fifty Shades was coerced and beaten in a way that she frequently said was hurting her (to my recollection). The list goes on and on…

As to the original post, I’ll add my praise to the rest. I think it’s a fascinating read, and I wish more critics would grapple directly with how power is exercised and transmitted. Thanks for the writing!

Hmmm…I don’t think Bella in Twilight is really in an abusive relationship, exactly. I mean, lots of people read the relationship with Edward as stalker-y, but the fact remains that Bella is certainly never raped,and Edward never hurts her. She also has no lack of agency (it’s her decision to become a vampire, over Edward’s wishes) and she really enjoys being superpowered. Also, Meyer is pretty careful to show that Bella is a potential super-vampire *before she meets Edward.* She’s into Edward and vampires because she’s a vampire, not the other way around (she can smell blood before she even meets Edward, for example, and she blocks his mind-reading powers from the first.) Sooo…I don’t think she really fits into this reading, which is maybe possibly why people hate her so much.

Wonder Woman also isn’t traumatized before she gets her powers (at least in the original version of the comic.) So…there are exceptions, though I think it’s certainly the case that rape revenge does very often define/limit women’s agency.

Oh, and I think romance novels are also a place where rape/revenge logic re female agency doesn’t usually work (I don’t know that it really does even for 50 shades, honestly….)

Hmmm. I have admittedly read neither Twilight nor Fifty Shades (I have, perhaps prudishly, avoided both like the plague). I got the abuse analysis for Twilight from comments that floated around for awhile that Bella and Edward’s relationship meets all 15 defining criteria for an abusive relationship as defined by the National Domestic Violence Hotline (http://www.thehotline.org/is-this-abuse/). For reference, meeting a single one indicates you should call them, as per their guidelines. I posted the link just because I do not have solid knowledge of the book. If you’re interested in comparing with the criteria, your analysis will certainly be better informed than mine by far.

As for Fifty Shades…again, I have no solid knowledge of the plot, so I’m shooting from the hip with that one. All I know is the basic outline that Ana signs much of her autonomy away to a man who comes close to physically injuring her without her full knowledge of his actions. That understanding is almost certainly incomplete, at best, but that doesn’t sound like agency without victimization.

And on romance novels, I agree. They seem to have a much easier time imagining and understanding how women can exhibit power and agency without being victimized or destructive.

Ha! I only saw the first Twilight film and I only made it one chapter into the audiobook of 50 Shades (and I felt obligated on that one). But I did make it a whole half way into Maleficent, up to the “rape scene,” actually.

I think Petar’s point about Maleficent’s agency as contingent upon violation and only ever “evil”/destructive is a very dominant motif in storytelling with very real consequences in how we understand and/or think female agency. I’d say it might be related to the thesis I posited in the 8 Minutes piece: that female sexual agency is only ever inverted, so that when women act as sexual agents they are figured as victims, and when they are victimized they are figured as sexual agents. And I think it makes sense in relation to BBHMM, too.

In relation to how this culture treats real rape victims, as opposed to fictional characters… I’ve been thinking about this all week, actually. I’ve been trying to think of any sort of instance that I have ever heard of or witnessed personally wherein the woman wasn’t pilloried and demonized (and much more so than the man/men). Saying you’ve been sexually violated out loud seems to be taken as proof of malevolence and evil intent, even when there’s overt proof, even in a case as extreme as Steubenville.

To link this back to Kate’s post, this would be the power (Maleficent-like) that we see or maybe even *think* we see, right? But it’s the power to designate and diagnose as evil, unstable, hysterical (that knowledge) which goes unseen and un-interrogated… I think?

Peter, the thing about Twilight and 50 Shades is that the relationships aren’t figured as abusive within the narratives. So within the narrative, it’s not saying that you need to be injured as a woman to gain power. They’re not rape revenge stories because the books don’t see the women as being raped.

You could argue about whether the relationships are abusive without the books realizing it. But I think, whichever way you take it (and for better or worse), the dynamic is very different from rape/revenge stories, where the point is that the women have been abused and are thus spurred to violent action.

And yeah…Twilight doesn’t fulfill most of those criteria—and I’m not sure it even gets to one. Edward certainly never physically hurts her (he’s terrified of physically hurting her, in fact.) Never puts her down. He makes some effort to control her, but she mostly thwarts him, in some cases by telling him to cut it out, at which point he cuts it out. 50 Shades comes a lot closer (and is generally a worse book in most ways.)

good thing that Kipnis wasn’t submitted to a grueling Title IX investigation then, right?

Oh, Poor-a Laura!

You realize she used rape and assault cases in defense of student-prof sexual relations, right? Read that again. She used rape and assault cases to say that student-prof sexual relation are A-OK! She didn’t use those happy marriages she refers to in the first paragraph.

Firstly, that *is* secondary trauma to the victims of Ludlow. It’s retaliation whether she meant it or not. And yes, absolutely: A chilling effect for the entire campus. Secondly, talk about betraying your cause! Sex-positive men and women should be FURIOUS at her! So, why is she NOT chemically castrated and dangling by her toes? The students, though, they seem to be.

PS — I won’t continue being this aggressive, but I’ve been thinking ‘Poor-a Laura’ for a while now, and I had to use it somewhere. And for the rest of what I wrote: Man, folks!…..

I don’t think the title ix investigation was a good idea…but I don’t know that it sounded exactly “grueling”. It sounded annoying, and then she was cleared…and then she got to write about it for the Chronicle, a gig which pays very well (in my experience) and which garnered her massive sympathy, visibility, and prestige. Meanwhile, as Nix says, students who have much less institutional power and who quite possibly have been sexually assaulted and raped are pilloried in the media, and have little or no ability to get their voices heard (the Chronicle isn’t going to them to get their side of the story, that I’ve seen…if they can even talk about it at all given legal proceedings.)

For someone who has such contempt for those who (in her view) portray themselves as victims, Kipnis has done a masterful job at turning her own extremely dubious narrative of persecution into a celebrated public identity.

As an aside, since we’ve mentioned Cosby and Fuchs, I’m throwing these two articles on Jian Ghomeshi out there, for anyone who is interested in cases like this:

http://www.nothinginwinnipeg.com/2014/10/do-you-know-about-jian/

http://www.slate.com/articles/double_x/doublex/2014/11/jian_ghomeshi_allegations_i_wasn_t_surprised_to_hear_them_does_that_make.html

And I’m taking a breather. :)

@Nix66, I read your comment and question this morning and spent most of the day mulling it over. Thanks for such a compelling inquiry–most of my work is on empathy and violence, and I didn’t want to test the readers’ patience with a longer discussion that diverted into that territory, but that’s precisely why I was so drawn to Hannibal in the first place: Will’s empathy.

In terms of the reading I provided in the essay, I think it has to be read as disqualified knowledge, but that is by no means the only way to read it. More on that in a minute. First, the essay’s terms here are talking about this narrow definition of power that’s being promulgated by Kipnis and some others, in which power must mean the capacity for serious and obvious harm, rather than subtle damage by degrees, which is why I see (in this context) Will as being so utterly debased. Even in his attempts to leverage his own knowledge in the series (as with students’ attempts to leverage theirs, as you noted), he’s marginalized, mocked, and ultimately subject to “disciplinary procedures” (if I’m sticking with Foucault here). I absolutely agree that the students “were criticized for not having had sufficient power” (and what a perfect way of distilling the issue).

That said, there’s another approach I find equally compelling, which has Will as the vanguard of re-ascribing both agency *and* (more importantly) rationality within emotive connection with others (it’s termed empathy in the show, but I’m not sure that’s the right term). Will is, after all, an object of fascination for Lecter, and I use the term “object” intending to preserve its other meanings as well. However, Will also seems–at the beginning of the series to be utterly evacuated of any interiority of his own–we primarily see him as a vehicle for others’ actions and desires, a medium rather than a subjectivity in his own right. This is something that changes after his stint as the accused and incarcerated possible serial killer–his personality beyond his “disorders” emerges. The subjectivity was always there, of course, but it’s this strange moment in which we realize as viewers that we have been so invested in Lecter’s view and ideas about Will (as well as Jack’s and Alanna’s) that we’ve rarely bothered to consider Will’s feelings.

And that’s where the idea of subjecthood as necessarily stable comes in–is it? Can Will be a subject given what he’s “best” at? Does adopting the perspective of another foreclose the self? I’m still playing with the possibilities here, but you can see where I’m going. What’s your take?

@Petar Duric, thanks for reading! And I’ve been meaning to watch Maleficent for some time, but have yet to see it. I’ll have to check it out this weekend.

And thanks all for the continued discussion of female agency. I couldn’t get into Twilight or 50 Shades (I did watch the movies for the former because my students loved them–I found them to be less about actual vampires and more about emotional vampirism inflicted on the audience).

As to the Kipnis case, Noah and Nix66 have already admirably addressed the issue raised. The more I’ve thought about it, the more I’ve been inclined to see it as a generational rift as well. I was thinking of the Abraham Simpson “Old Man Yells at Cloud” meme that was going around–labelled as “Justice Scalia”–a few weeks ago. I’m inclined to think there’s something in that.

The Twilight books are significantly better than the films, IMO. No one should read 50 Shades if they can avoid it, though.

At the risk of expanding the conversation by another order of magnitude, there are two writers in particular that present a fascinating view of how to exercise power: Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett. I understand Gaiman is on the List of Hated Things here, but I adore his writing, particularly on Sandman. He and Pratchett both use a common trope which seems to never get old whereby the most powerful characters in their stories are the ones who operate within the boundaries of society in unexpected ways. For example, Gaiman’s version of Lucifer, who gets his own excellent spinoff from Sandman, is feared and respected throughout the novel’s universe because of his cunning. But his cunning takes the form of an absolute and thorough knowledge of “the Rules.” In other words, Lucifer knows exactly how to behave in virtually any culture or tradition, and he has such a complete understanding of these rules and the motivations of various actors within them that he seems to glide through terrifying circumstances. His power comes from adaptability, and his knowledge and ability to leverage existing systems of power, and convert them into, “psychological force” in much the same way you describe Lecter doing, Kate. It’s also a rare re-envisioning of power that does not require victimization in any particular direction.

Kate: Calling him a medium is very just; I’m still grappling with what that might mean for agency and/or even the possibility of agency, both his own and how he enables others. On the one hand he constitutes the subjectivities of others. On the other, he is in no way stable and cannot be (based on what I’ve seen of the show/maybe there was a great change). His skill is not separate from his instability as a subject.

Petar, what a fantastic connection! Full disclosure: Mike Carey’s version of Lucifer is my favorite comic series of all time. I even have a couple of scholarly articles on it (mainly on Elaine and the Genesis retelling as well), but I don’t think I ever would have made that connection between the two characters. You’re right–adaptability and knowledge of “the rules” is the key. Power as that which operates within the parameters, but to the detriment of the powerful (although this doesn’t always hold true in either case–broad swaths, that works, but neither Lecter nor Lucifer is exactly opposed to leaving bodies in his wake).

Although, I think that adaptability can cut both ways–I don’t think we could have a woman of color play the same role because she wouldn’t be received in the same way (because she’s already socially “marked”). So, in a way, Lecter and Lucifer could be read as the danger in the “unmarked” white male. With that said, we could read both as an indictment of the rules along a different path as well.

Hmm. This is a great idea for a more extended discussion.

Nix66, is it splitting hairs to say “re”-constitutes? One of the things I’ve wondered about with the show was whether or not his “This is my design” is a full empathetic occupation or an imaginative leap. And, bracketing that for a minute, should a subject be stable when they’re operating along both emotive and rational axes? That binary opposition of rationality and emotional capacity has served us ill for centuries, so can a stable subject exist in a state of both emotive and rational upheaval? I don’t know how far you’ve watched, but the third season is doing something very different–I’m not sure what yet, though. He’s an eminently rational character with control over himself in a way that eluded him in the previous seasons. However, he’s also lost something, and we don’t have any of the insertions into a different subjectivity. You may be right, given the way the show is playing out. Although I’d like to believe that he was actually a more stable subject when he was in possession of his full faculties, as damaging as they could be. But that’s just what I’d like to see.

Ha! It’s not splitting hairs to stress the “re.” My only struggle now is that I do not believe in a stable subject. There’s no “sane” mind unless we have an “insane” mind. And we all get sick and die. So the subject, I feel, needs to be dismantled and done away with. It’s not good for us as a species.

So, are we saying that Lecter *is* rational and not emotive? Or that he appears to be?

@ Peter Duric

‘In other words, Lucifer knows exactly how to behave in virtually any culture or tradition, and he has such a complete understanding of these rules and the motivations of various actors within them that he seems to glide through terrifying circumstances.’

I would say you hint here at why neither Mike Carey’s Lucifer – who in my opinion doesn’t have much in common with Neil Gaiman’s – nor Bryan Fuller’s Hannibal works as (nor were they supposed to work as) a commentary on institutional power. They are individualist fantasies: The individual person who is so exceptionally smart that he – it’s usually a he – can manipulate all the systems, and do whatever he wants to anybody, up to and including murder. By their nature, they are in denial about the actual power of the institution. (In terms of the Kipnis controversy, this puts them essentially in her corner.)

For something similar from a previous generation, see Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest; or A Fistful of Dollars, which restored the full dumbness of the original story after Kurosawa classed things up a bit in the interim in Yojimbo.

@ Noah

‘The Twilight books are significantly better than the films, IMO.’

How so?

It’s been a while since I read the books or films..I think the films (at least first couple; didn’t see the last) lost some of the weirdness and generally hollywoodized things. I have a short review of Eclipse here.

Thank you!

@Graham

This whole concept of how to exercise power, illustrated by Lucifer, is absolutely individualist, because it depends inherently on the ability of the person exercising the power to maneuver nimbly and freely throughout a culture. Without nimbleness, the exercise of power doesn’t work. But the power isn’t really manipulation, at least not how I view it. In some ways its worse. To preface, Lucifer certainly has copious amounts of straightforward power. His supernatural and physical abilities are extremely well-developed. But the brilliance and weirdness of the character is that his ambitions far outstrip his powers, and so he needs to convert his power to a higher Voltage, so to speak, and he does so nudging little bits and pieces of a situation into certain situations, and then he sits back and waits for events to unfold, all the while merely positioning himself so that he reaps the benefits at the end. In other words, he gives everybody just enough rope to hang themselves, and then he knows that what will come out of the situation will be some bizarre Cat’s Cradle to his benefit. His power isn’t really manipulation, it’s forecasting and positioning.

@Kate

Rolling off of that point, I think you’re right that a woman of color (or just a POC in general) would have a MUCH harder time exercising this kind of ability to its fullest extent, because it depends on social mobility. Lucifer’s power functions correctly because he can move freely through many different traditions and social environments. But if you are a POC, your social mobility is already restricted, so your ability to position yourself to reap the rewards of your prediction are less than a white male Lucifer’s are. Lucifer (the book) as well as many of Gaiman’s writings seem to underwrite this point by constantly stumbling on representations of POC. For the most part, they are very nuanced and avoid caricature, but none of them operate on anywhere near the level of Lucifer, like when Lucifer, to put it flippantly, does Japan better than Japanese people. There is a LOT more to unpack about Gaiman’s/Pratchett’s/Carey’s representation of power and POC, but that seems a good summary.