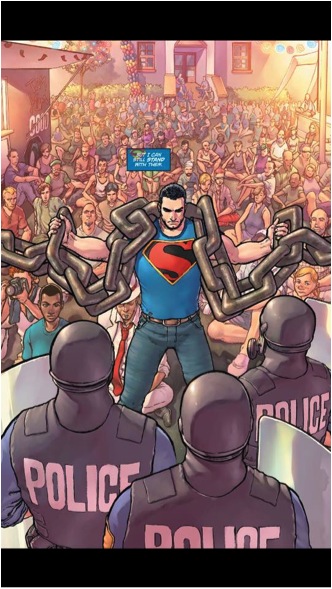

The July 2015 issue of Action Comics (vol.2 #42) has garnered instant praise from critics. In the current storyline, Superman has his secret identity revealed and his powers severely dampened. In a further controversial and news-making development, cops and SWAT teams confront local Superman supporters and engage in a violent attack that prompts the Man of Steel not only to defend the neighborhood from the onslaught of police, but to end the conflict with a right cross to the chief officer’s face.

The images of a riot instigated by police naturally conjure up memories of Ferguson Missouri. As a result, the issue has led such online publications as International Business Times and Business Insider to label the story “gripping”, “breathtaking” and “compelling”.

So why is it so lousy?

I’m unsure what’s worse, the lazy storytelling or the mindless praise for it. It’s as though the aforementioned websites happened upon Google images of the issue and quickly churned out a glowing recommendation for the benefit of appearing both pop culture savvy and socially conscious.

In the sotry, the denizens of the local neighborhood in Metropolis, calling their block “Kentville”, are showing their support of Superman, now publicly known to be Clark Kent. While Superman is away battling a giant monster, a SWAT team arrives to break up the assembly, and within minutes fire an errant canister of tear gas into the crowd. One of the citizens knock it back towards the police, and the neighborhood resigns to sit on the ground and commit to a silent protest, welcoming the oncoming march of the cops who are more than willing to beat everyone to a pulp. Superman arrives with a giant chain held over his shoulders, standing between the SWAT team and the crowd. The lead cop named Binghamton announces that he and the other police will beat everyone on the block including Superman, and then proceeds to do so.

With the Ferguson analogy inelegantly at the forefront, let’s describe how this doesn’t work and what makes its evocation of recent events improper.

1. The SWAT team is brought to disrupt the gathering for Superman without the presence of any sort of protest to disrupt. Unlike in Ferguson, where at the very least tensions had built over an already ever-present sense of racial profiling, the cops are only arriving due to the mustache-twirling machinations of the lead policeman Binghamton.

2. Binghamton’s problem isn’t portrayed as any sort of prejudice or distrust towards Superman because he’s an alien. He openly admits that he’s sick of the praise and adulation Superman has gathered over the years at the expense of the public’s recognition of regular police and firefighters. The conflict isn’t borne out of systemic and long-held prejudices; it’s created by one man’s jealousy of a fictional character.

3. As a result, the conflict between the police and Superman and the protestors is nothing more than a bad guy and his army attacking innocent civilians. It makes the conflict into a too simple case of good vs. evil, removing any semblance of reality. The situation makes the police into supervillains, so that they’re easy to recognize and easy to fight.

Thus any resemblance to tensions in the real world is removed, and the conflict can go down as easily as any other superbattle. Moreover the way in which the storyline uses the imagery and context of racism is nothing short of appalling.

For one thing, the image of Superman holding a gigantic chain to put himself between the police and the crowd is quite blunt. It’s no doubt supposed to represent shackles of oppression imposed by white authority, but in the hands of a white superhero, it ends up coming across as unearned cultural appropriation. A figure of super-authority such as Superman, powers or no, can’t subsume himself in the community of the subjugated masses when he has traditionally aligned closer to that of a policeman for most of his life. It rings hollow and condescending, as if the story is parodying the resistance to police brutality.

Worst of all is the fact that the overwhelming majority of the people the police are attacking, the ones Superman is defending and the ones that serve to match the Ferguson protestors in this analogy, appear to be white. The firefighter who puts herself at the front of the crowd is recognizably black, but the neighborhood consists of a veritable “who’s who”, or “what’s what” in ethnic diversity. Folks young and old with large noses and middle class clothing make up the whole of the group, with black people ironically the minority of the whole block. This shows that the policemen’s grudge is really no more than a plot necessity that has no bearing in reality. A line by a Hispanic character reads “This is America! This is what I fricking fought for! I’m not gonna let them take that away!” which is answered by the firefighter “If you fight, people are gonna die. Our people. Is that what you want?” This would resonate so much better if both characters were black, not to mention if a majority of the crowd was. As nice as multiculturalism is to see in mainstream comic books, it doesn’t make sense within the context of the story this issue is trying to tell. The police are shown to have such a blasé disdain for the citizens they’re about to brutalize that it makes the story come off as anti-police propaganda more than anything. There’s no nuance, no sense that this could at all take place within the real world.

Superman is supposed to be a Champion of the Oppressed as evidenced by his original Golden Age adventures and later stories as well. He is most effective when battling real world society ills that his readers face every day. So what’s the point in making a story where there’s no actual ill of society or systemic oppression for him to overcome? Was the writer Greg Pak too gun-shy to actually engage in the topic his story’s imagery advertised? The connection between police brutality and racism is not a very difficult concept to grasp, and who better than the world’s first superhero (other than black superheroes) to tackle it head on.

Ultimately the story serves to say “Superman’s one of us!” in a way which doesn’t actually say that. He, like many other costumed heroes, is just like us presuming that we too have a specific and unrealistic villain to face and defeat, rather than the innate problems in our society. As much as people like to lambast the Denny O’Neil/Neal Adams Green Lantern/Green Arrow series, that comic at least had the respectability to tackle the problems it saw head on without thinking of misrepresenting it. It named what it saw as what it was and didn’t ignore difficult conversations in a bid for misplaced solidarity. I believe that super hero comics can truthfully engage in contemporary topics—that they can be relevant and contribute to a national conversation. It’s so unfortunate that when it comes to the most pertinent conversation in our nation today, the best superheroes can offer is Action #42.

_______

This is part of our ongoing series, Can There Be a Black Superhero?

In Part 3 of my series on Storm (you can ready part 1 here and part 2 goes live on Tuesday, part 3 the week after that) I mention those O’Neil/Adams Green Lantern/Green Arrow comics in a similar way to what you mention here. They may address race in an awkward and sometimes troubling way, but at at least they address it – mention it, call it by name. Once upon a time Jon Stewart (the best Green Lantern) even tried to use his power to address some basic racial inequalities. In way I think things are worse for black superheroes and other PoC characters in comics today than they were in the 70s.

Maybe things were better in the 70s…but really this sounds pretty familiar in terms of how superhero comics deal with race. Half-assed clumsy appropriation by people who know little and care less about the issues involved. It’s embarrassing.

Donovan, I would appreciate superhero comics that embraced nuance, that used real world complexity in storytelling and setting, but the resultant narratives would not be superhero comics. To expect Greg Pak to distill the public unrest displayed in Ferguson, MO and Baltimore, MD into a Superman comic asks far too much of the writer and his chosen genre.

Further, Kentville appears a rough analogy for Occupy Wall Street, not #BlackLivesMatter. Here, the static, motionless community-within-public-space-as-protest/ celebration reflects Zuccotti Park and its many imitators, not the energetic chants and daily marches we associate with anti-police brutality protests today. While it’s fair to assert that the story rips the ‘nonviolent public protest versus jackbooted thugs in blue’ narrative from progressive news outlets, it’s not clear from what you presented that a connection to Ferguson and Baltimore exists, visually or otherwise.

Donovan, if you’re right, and “superhero comics can truthfully engage contemporary topics”, then the repetitive failure from this genre to produce socially relevant material unmasks this premise as faith. You’ve analyzed a superhero comic written by a person of color that openly references progressive criminal justice perspectives, and given your analysis, it still fails. If Pak intended Action #42 as a simplistic commentary on Ferguson and Baltimore (though I don’t think that’s happening here), then his largely whitewashed and revoltingly basic presentation of martial police overreach suggests that the narrative strictures that prevent meaningful political discussion in superhero comics have not been removed. Maybe it’s time to recognize that they cannot be lifted.

This reminds me of The Movement, another embarrassing attempt at relevance. Despite being earnest about diversity, the end result was like Justice League Detroit mixed wotj warmed over generic 90s style art and writing. At least this has decent work by Kruder.

Given the quality of Gail Simone’s other work, I can’t help but wonder if The Movement’s failures were as much about DC editorial and production issues as her writing outside her comfort zone.

I think it’s appropriate to invoke Green Lantern/Arrow, but I don’t think that things were necessarily better in the 70s. It’s that the good and bad of the work can be appreciated within the limitations of the industry and white progressives at the time.

The problem is the 70s level of not entirely insulting “relevance” is now DC’s threshold of good enough, while the potential to do a much better job has increased significantly.

Adams and O’Neil were 31 and 30 (and O’Neil had more varied life experiences than most folks writing comics today). Their flaws weren’t cynical, i.e. knowing little and care less about the issues, but mass market creatives on a deadline squeezing politics and art they cared about into at best a shaky vehicle.

I wonder if their 30 year old selves would argue their work was perfect let alone a benchmark for the next few decades. Alas it has been, and it mostly doesn’t rise to even the effort to understand shown by “ripped from the headlines” cop shows.

I think Gail Simone can be pretty uneven…not to exculpate DC editorial, but while I often like Simone, I think she has enough blind spots that I wouldn’t want to let her off the hook either (I haven’t read the Movement, though, so don’t know what I think about that.)

After reading 2/3rds of her Batgirl run, I don’t like Simone’s writing much at all. Ambition kills nuance it seems with her and writers like her.

Anybody wonder Strange Fruit from Waid and Jones which doesn’t have the editorial restrictions a Big 2 does is gonna be better about race and superheroes?

Robert: There was a interesting take on Strange Fruit on Women Write About Comics: http://t.co/fVe55dKzYN

I found the beginning labored, but the criticism of the comic itself was convincing.

Yeah…the beginning is not good. I mean, “white people should not write about racism” as a theory seems pretty confused. Not that Huck Finn or Crane’s “The Monster” have to be considered perfect in every way, but I think they suggest strongly that there’s precedent for white people writing about racism in thoughtful and moving ways. And the bit where she has to back and fill and pretend that Strange Fruit should get a pass because it’s written by a Jewish guy—as a Jew, I really feel strongly that we don’t get to be honorary black people in an American context.

The comic sounds bad. And comics needs more white creators. And having these white creators write this comic seems to have been a bad idea. I can get behind all of that.

Oh, and I think James is being waaaaay too kind in his suggestion that superhero writers can tell Ferguson from Occupy from their own butt. I have no trouble believing that this is meant to be a Ferguson reference as Donovan says, albeit an extremely garbled one.

Mediocre superhero comic gets mainstream press coverage for ham-fisted social commentary, full story at 11

Also, Dog Bites Man Shock

Except this essay isn’t about “superhero writers” but a specific failed story by a specific author, Greg Pak. Before making broad generalizations about what a writer of color can discern from their own butt, it’s worth seeking a bit more context about their politics, background, etc.

I think it’s being well informed and aware can still result in a tin eared literary analogy. It strikes me as having similar aspirations to Kyle Baker’s Truth, a much better effort which ran up against the limitations of fitting ideas around a mainstream white superhero.

I’d also have to agree with Lamb: given the production schedule and other things, this seems like a bad Occupy Wall Street analogy made worse by being published after recent events.

@ MrFengi

So, what, because he’s Korean he knows from Ferguson?

Yeah, Noah: I just finished reading Action #42. Kentville’s Occupy, not Ferguson; MrFengi’s point about production schedules and editorial influence makes sense here. Judge Pak’s script wanting if you like, but he’s not talking about Ferguson in Action #42.

Further, Greg Pak’s the guy who gave us Robot Stories; it’s difficult for me to imagine him incapable of the political and social nuance required to discuss racial and social unrest. But whether through DC editorial’s influence or simple bad writing, this issue makes clear that attempts to inject sociopolitical commentary into the superhero genre fail.

And if the 70’s presents some utopia for discussing race in comics, we’re all in trouble.

Why so keen on finding a negative angle on progressive entertainment which gain mainstream recognition? It was the same with Fury Road and Uncle Sams Cabin.

It could well be occupy not ferguson; I haven’t read it. As with Jews, though, I’m pretty leery of saying that Korean-Americans somehow are in a privileged position to understand the black experience in the U.S.

Oh, and Kasper…not sure what you mean re Fury Road? We’ve had a couple of pieces about it on the site…I guess one was skeptical, but the last was more positive.

though…mainstream progressive entertainment is often quite dumb and not especially progressive. I’m sure Donovan would have much preferred to be enthusiastic about this. But just because something bills itself as progressive doesn’t mean its smart or helpful.

J., I can definitely see some Occupy Wall Street connections here. More than I first did. There’s still some blatant Ferguson invoking though, that much is still irrefutable. Mainly in that scene between the firefighter and the Hispanic citizen. The thing though, again, is that the crowd aren’t necessarily protesting anybody. The resistance to police brutality is demonstrated in this issue through naked brutality against people literally minding their own business. The idea of things like stop-and-frisk, driving-while-black and other occurrences of cops picking a fight are sooner to be recalled in one’s mind rather than these people protesting the police or any sort of higher authority or 1% type of group.

There’s no clearer instance of Pak wanting to do his opinion piece than that scene where the black firefighter says that if they fight back to defend themselves, they will die. Later there’s a scene of a black cop being attacked by a white cop. That’s not an accident. Pak knew what he was going for, and it was Ferguson.

Donovan, I disagree. The Kentville supporters are “literally minding their own business” in a public space under local control. This ‘lack of protest as protest’ makes Kentville a dead ringer for Occupy, and the police overreach under Binghamton a clear parallel to the overreach used to dismantle Occupy Oakland. This isn’t Ferguson; you’re simply associating the Ferguson protests with this comic because Ferguson resonates for you.

There’s nothing wrong with recalling stop and frisk, or driving while Black, or generally unwarranted police scrutiny when reading superhero comics, of course. But the superhero comics themselves often fail to discuss any of those topics, and Action Comics #42 is no exception. Kentville’s leader’s pleas for nonviolent calm before oncoming martial sanction from SWAT personnel does not directly reference Ferguson; it references every nonviolent protest leader since antiquity. This is just as much Gandhi and MLK as it is Kent State and the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

That’s the problem — the reader endures a Seinfeld protest about nothing turned into a violent spectacle by an easy-to-despise police commander with as much professionalism and restraint as former police corporal Eric Casebolt. None of this proves specific enough to warrant a Ferguson analogy, and most of the public protest action described in the comic reflects the Occupy model, if anything.

Donovan, we agree that Action Comics #42 proves badly written, at best. But your argument above asserts a direct connection between this comic and recent events in Ferguson and Baltimore that the facts do not support. To reference Ferguson and Baltimore the protester crowd would have to engage movement of some kind: marching, chanting, fists raised in defiance, something. Kentville was a boring party made notable by comically unwarranted excessive force. We can’t just apply whatever lenses we like to superhero comics; critique Pak for what he wrote, not for what he didn’t.

I disagree, still, but I plan on asking Pak about it as I’m currently attended San Diego Comic-Con.

And maybe we necessarily “shouldn’t” apply “whatever lens we like” to superhero comics, but God knows we can. And will still do, all of us.

BTW James, for my own part, there is a long a way between “sometimes I wonder if the 70s were better for black characters in comics” and “the 70s were a racial utopia.” “Better” does not imply “good.”

So I made it a point to track down Greg Pak at San Diego Comic-Con, as I go every year to report for the Batman Universe.net. I attended the Superman panel but the Q/A segment had a moderator who sent out someone to vet the questions, so I decided to wait until after the panel ended to have a real conversation with Pak about the issue. I found him signing a half hour later at the DC Booth.

I asked him straight up if the events in issue #42 of Action were inspired by the events in Ferguson, and he said that they weren’t. They weren’t inspired by any event specifically, not even the Occupy Wall Street movement, as police brutality had been a thing happening for decades (obviously). I then asked him since the main cop bad guy is such a clearly defined tool if that doesn’t turn the subject matter into a cynical parody and lessen the weight of the story implementing real life events. He answered that he’s trying to write a Superman story first and foremost, and that there’s no real attempt to make a statement on social issues within the pages of Action Comics, to which I said that was too bad since Superman premiered with Action in attacking social issues.

I got the sense that Pak felt like a deer in the headlights when I was talking to him. I will him him full credit in that he took as much time as he could (about 15 minutes) in the middle of his signing to discuss with me his reasoning and perspective in writing Action #42 and in no way tried to give me a simple answer and no take my concerns seriously. I really felt that he was willing to engage in a true examination of the story and tried to justify how he told it. It doesn’t change the fact that it’s full of holes, but at least from a conscious standpoint I don’t think he meant to write the issue cynically. He said ultimately it’s up to the readers in what meaning they take away from the comic.

That doesn’t really do the defense of the issue any good whatsoever, but at the very least I’ve no ill will against the guy. It goes back to the simple problem of trying to appear socially conscious and relevant through half-measures and oversight. Same old story I guess…

That’s pretty fascinating. Thanks for doing that and reporting back.