I grew up in a universe in which electrons were like planets orbiting double nuclei “suns” in tiny solar systems. It was a metaphor, a useful one at the time. Then new data required a figurative upheaval. Now the electrons of my children’s universe mingle in clouds. Electrons always have—chemistry teachers of my youth just didn’t know better. Any change in metaphor is also a change in reality. That’s why the in-between state, when the old system is collapsing but no new figurative principle has risen to organize the chaos, is so scary. Metaphors are how we think.

During the second half of the 20th century, the literary universe was a simple binary: good/bad, highbrow/lowbrow, serious/escapist, literature/pulp. Like Bohr’s atomic solar system, that model has lost its descriptive accuracy. We’ve hit a critical mass of literary data that don’t fit the old dichotomies. Margaret Atwood, Michael Chabon, and Jonathan Lethem are among the most obvious paradigm disruptors, but the list of literary/genre writers keeps expanding. A New Yorker editor, Joshua Rothman, recently added Emily St. John Mandel to the list: Her postapocalyptic novel Station Eleven is a National Book Award finalist—further evidence, Rothman writes, of the “genre apocalypse.”

Rothman resurrects Northrop Frye to fill the vacuum left by the collapsing genre system, but the Frye model’s four-part structure (novel, romance, anatomy, confession) is more likely to spread chaos (“novel” is a kind of novel?). Another suggestion comes from a holdout of the 20th-century model: The critic Arthur Krystal believes an indisputable boundary separates “guilty pleasures” from serious writing. Perhaps more disorienting, Chabon would strip bookstores of all signage and shelve all fiction together. Ursula Le Guin, probably the most celebrated speculative-fiction author alive, agrees: “Literature is the extant body of written art. All novels belong to it.”

I applaud the egalitarian spirit, but the Chabon-Le Guin nonmodel, while accurate, offers no conceptual comforts. The Bohr model survived even after physicists knew it was wrong because it was so eloquent. Even this former high-school-chemistry student could steer his B-average brain through it. A vast expanse of free-floating books is unnavigable. A good metaphor needs gravity.

To explain the lowly lowbrow world of comic books, Peter Coogan, director of the Institute for Comics Studies, spins superheroes around a “genre sun”—the closer a text orbits the sun, the more rigid the text’s generic conventions. It’s a good metaphor, which is why most models use some version of it, including all those old binaries: The further a text travels from the bad-lowbrow-genre-escapist sun, the more good-highbrow-literary-serious it is. But because metaphors control how we think, solar models are preventing us from understanding changes in our literary/genre universe. It looks like an apocalypse only because we don’t know how to measure it yet.

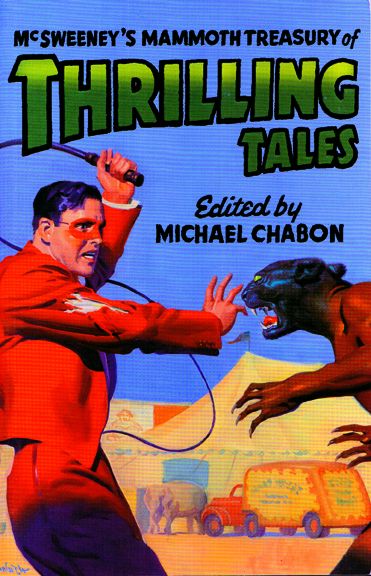

Chabon is often credited for starting the genre debate with “Thrilling Tales,” the first genre-themed issue of McSweeney’s, published in 2003—though the Peter Straub-edited “New Wave Fabulists” issue of Conjunctions beat it to press by months, and surely Francis Ford Coppola deserves credit for rebooting the classic pulp magazine All-Story in 1997. Coppola has since published luminaries like Rushdie and Murakami, even if, according to the old model, those literary gas giants should exude far too much gravitas to be attracted to a lowly pulp star. And what becomes of second-class planets when their own creators declare them subliterary? According to S.S. Van Dine’s 1928 writing rules, detective fiction shouldn’t include any “long descriptive passages” or “literary dallying with side-issues,” not even “subtly worked-out character analyses.” For Krystal, if a “bad” novel becomes “good,” it exits its neighborhood and ascends into Literature. The Krystal universe of fiction resolves around the collapsed sun of a black genre hole, and his literary event horizon separates which novels are sucked in and which escape into the expansive beauty of literary fiction.

Lev Grossman, author of The Magicians, calls that argument “bollocks, of the most bollocky kind.”

“As soon as a novel becomes moving or important or great,” he retorted in Time, “critics try to surgically extract it from its genre, lest our carefully constructed hierarchies collapse in the presence of such a taxonomical anomaly.” The problem is nomenclature. Grossman defines genre by tropes: A story about a detective is a detective story—it may or may not also be a formulaic detective story. Krystal defines genre exclusively by formula. Substitute out the ambiguous term, and his logic is self-evident: When a formula novel ceases to be primarily about its formula it is no longer a formula novel. Well, duh.

Grossman’s trope approach makes more sense, but Krystal is nostalgic for more than generic categorization. The old dichotomy was seductive because it was (as Grossman points out) hierarchical, performing the double organizing duty of describing and evaluating. By opposing “literary” to “genre” and then conflating “literary” with “quality,” Krystal is forced to make some ineloquent claims: “All the Pretty Horses is no more a western than 1984 is science fiction.” While technically true (Cormac McCarthy’s and Orwell’s novels are genre to the same degree), such assertions are forgivable as long as they are exceptions. But when those free-floating planets represent the expanding norm (in what possible sense are Atwood’s, McCarthy’s, and Colson Whitehead’s most recent novels not apocalyptic?), Krystal’s model collapses.

At least the good/bad dichotomy has collapsed. It never made categorical sense, since a “bad good book”—a poorly written work of literary fiction—had no category. Literary fiction is another problematic term. It traditionally denotes narrative realism, fiction that appears to take place here on Earth, but it’s also been used as shorthand for works of artistic worth. With the second half of the definition provisionally struck, we’re left with realism. Its solar center is mimesis, the mirror that works of literature are held against to test their ability to reflect our world. Northrop Frye declared mimesis one of the two defining poles of literature, though he had trouble naming its opposite. Frye located romance—a category that includes romance as well as all other popular genres (and so another conceptual strike against the Frye model)—in the idealized world, so Harlequin romances are part fantasy too (real guys just aren’t that gorgeous and wonderful).

But any overt authorial agenda can rile mimesis fans. Agni editor Sven Birkerts panned Margaret Atwood’s first MaddAddam novel because “its characters all lack the chromosome that confers deeper human credibility,” and so, he concluded of the larger premise-driven genre, “science fiction will never be Literature with a capital ‘L.’” Atwood was writing in a subliterary mode because she had an overt social and political intention. So her greatest literary sins, for Birkerts, aren’t her genetically engineered humans, but her Godlike and so nonmimetic use of them.

Others have tried to balance the seesaw with poetic style or formula or sincerity, suggesting that literature is a wheel of spectra with mimesis at its revolving center. In the old model, mimesis was also the definition of “literary quality”: The closer a work of fiction orbited its mimetic sun, the brighter and better it was. Like the Bohr model, that’s comprehensively simple, and so little wonder Krystal is still grasping it: Literature is the lone throbbing speck of Universal Goodness surrounded by an abyss of quality-sucking black genre space. Remove “quality” from the equation and posit a spectrum of mimetic to nonmimetic categorizations bearing no innate relationship to artistic worth, and the system still collapses.

Quality could rest in that fuzzy middle zone, a literary sweet spot combining the event horizons of two stars: mimesis and genre. That middle way is tempting—and perhaps even accurate when studying “21st Century North American Literary Genre Fiction,” the clumsily titled course I taught last semester. I am requiring my current advanced fiction workshop students to write in that two-star mode, applying psychological realism to a genre of their choice. But it’s a lie. If quality is mobile, and it is, then no position on the spectrum—any spectrum—is inherently “good.”

Perhaps novels, like the electrons of my youth, orbit double-star nuclei, zigzagging around convention neutrons and invention protons in states of qualitative flux. It’s not just the text—it’s the reader. That’s a central paradox of physics too. “We are faced with a new kind of difficulty,” wrote Albert Einstein. “We have two contradictory pictures of reality; separately neither of them fully explains the phenomena of light, but together they do.” Light, depending on how you measure it, is made either of particles or of waves—and so somehow is both. That seemingly impossible wave-particle duality applies to all quantic elements, including works of fiction.

The cognitive psychologists David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano, in their 2013 study, “Reading Literary Fiction Improves Theory of Mind,”dragged the genre debate onto the pages of Science. Literary fiction, they reason, makes readers infer the thoughts and feelings of characters with complex inner lives. Psychologists call that Theory of Mind. I call it psychological realism, another form of mimesis. The researchers place popular fiction at the other, nonmimetic pole, because popular fiction, they argue, is populated by simple and predictable characters, and so reading about them doesn’t involve “ToM.”

Kidd and Castano are recycling Krystal’s “genre” definition, only using “popular” for “formulaic.” Their results support their hypothesis—volunteers who read literary fiction scored better on ToM tests afterward—because their literary reading included “Corrie,” a recent O. Henry Prize-winning story by Alice Munro, and the genre reading included Robert Heinlein’s “Space Jockey,” a detailed speculation on the nuts and bolts of space travel populated by appallingly two-dimensional characters. The science is as circular as Krystal’s: Stories that don’t use readers’ ToM skills don’t improve readers’ ToM skills.

If psychological realism is taxonomically useful for defining “literary” (and I believe it is), then here’s a better question: What results would a ToM-focused genre story yield? My colleague in Washington and Lee University’s psychology department, Dan Johnson, and I are exploring that right now. For a pilot study, we created two versions of the same ToM-focused scene. One takes place in a diner, the other on a spaceship. Aside from word substitutions (“door” and “airlock,” “waitress” and “android”), it’s the same story, the same inference-rich exploration of characters’ inner experiences. When asked how much effort was needed to understand the characters, the readers of the narrative-realist scene reported expending 45 percent more effort than the sci-fi readers. The narrative realists also scored 22 percent higher on a comprehension quiz. When asked to rate the scene’s quality on a five-point scale, the diner landed 45 percent higher than the spaceship. The inclusion of sci-fi tropes flipped a switch in our readers’ heads, reducing the amount of effort they exerted and so also their understanding and appreciation. Genre made them stupid. “Literariness” is at least partially a product of a reader’s expectations, whether you lean in or kick back. Fiction, like light, can be two things at once.

This wave-particle model may or may not emerge as the organizing metaphor of contemporary literature, but follow-up experiments are under way. We will survive the genre apocalypse. In fact, I predict we’ll find ourselves still orbiting the mimetic sun of psychological realism. The good/bad, literary/genre binary has collapsed, but the center still holds.

[This article originally appeared in The Chronicle of Higher Education in January 2015.]

‘Agni editor Sven Birkerts panned Margaret Atwood’s first MaddAddam novel because “its characters all lack the chromosome that confers deeper human credibility,” and so, he concluded of the larger premise-driven genre, “science fiction will never be Literature with a capital ‘L.’”’

^ These are obviously the words of somebody who’s very afraid that science fiction will be Literature with a capital L – but I think this is a symptom not of science fiction having become too good to ignore, but rather of modern ostensibly high literature having become too bad to be able to make any legitimate special claims for itself.

Maybe one limitation of science fiction is that theoretical scientific scientific advances basically don’t effect people’s lives very much (as opposed to the new inventions produced by those advances; of course, science fiction is about inventions too, but it always ends up caricaturing inventions that already exist – which you might as well just write about in plain old fiction.)

Oddly, Birkerts’ Agni is a great journal, publishing all kinds of genre-merging high/low lit, so I think his comment about Atwood and scifi in general is happily atypical.

I’m curious about how to carry this conversation slightly further into the even messier realm of Comic Books, which was touched on slightly in the article. A little tension is added because it requires a shift in medium as well as genre, but when I talk to some of my classmates about Comics, it’s common to hear them say, “Well, I’ve read some graphic novels. Memoirs, histories, not like, superhero stuff.” And superhero stuff is the topic to distance yourself from. Then, in addition, some prodding reveals that they have no experience with superhero comics at all. It reminds me of being in undergrad English classes and hearing classmates deride SF and Fantasy without having ever read a genre novel in their adult life. I’m not a literary critic (I’m attaining a Master’s in Biblical studies) so my instinct is to ask: what if anything can average readership do to improve the perception of their favorite genre pieces?

Tell the superhero comics snobs to read WATCHMEN. It’s on Time Magazine’s list of best novels of the 20th century. As far as most revered graphic narratives, I’d say it second only to MAUS.

Yeah, I think Watchmen is a good point of entry, but I think that avoids the issue of appreciating genre work. Watchmen is a superhero story that doesn’t behave like other superhero stories, it has a very fixed end in mind for one thing. I’m as guilty as anyone of pointing genre snobs to LeGuin, but I have to admit that I’m more interested still in getting those same people to engage material with less high cultural clout.

I think Watchmen does actually behave like supehero stories.

I guess it depends on what you’re looking for. A lot of superhero comics are crap. They’re also not really very popular. It’s hard for me to see why someone who isn’t a fan *should* engage with them. They’re not interesting; they don’t really have necessarily wide cultural impact or meaning. So why bother with them? I don’t think there’s any moral or intellectual imperative to do so.

There are good superhero comics, I think, like there are good anything. Watchmen is one example; the original Marston/Peter Wonder Woman comics are another. I like Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol; Dark Knight is fun; Astro City is pretty good. Kirby’s art is fun to look at; so is the Ditko Dr. Strange. I like G. Willow Wilson’s run on Ms. Marvel…

Whether Watchmen is a good point of entry depends on the kind of snob you’re dealing with. Somebody who thinks he’s too good for superhero comics but loved The Wire may be impressed. On the other hand, somebody who actually has a taste for good writing will find plausible excuses to despise the whole thing right from the very beginning (“abattoir of retarded babies”).

I guess most literary snobs would probably concede that Will Eisner’s The Spirit is pretty okay. It probably wouldn’t impel them to read anything else, though. But then, does that really matter? Without denying that superhero comics can be good, has there ever actually been one so good that not reading them is a major loss?

(Okay, there’s William Marston’s Wonder Woman – though I’m not sure how much it gains from being a comic book as opposed to a theoretical tract – but conceding that one, are there any others?)

I’d argue that Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns qualifies here, because it captures the Reaganomics’ 80’s paranoid tone so effectively. Urban crime and nuclear savagery threatened the American Dream’s true believers, and DKR purifies that fear in comic book form.

As a genre I suggest superhero comics have no utility whatsoever, but for people who do not remember the conservative hysteria of that time, DKR’s a useful primer.

@ J. Lamb

Interesting. Well, it beats The Bonfire of the Vanities, at least!

@ me

‘…though I’m not sure how much it gains from being a comic book as opposed to a theoretical tract…’ This was stupid.

I love Harry Peter’s art, and Wonder Woman the comic I think is (in part because of that) superior by a lot to Marston’s theoretical work. You don’t really get the same oomph from the fetishes in the prose stuff, among other things.

Hah! And I just saw you retracted; fair enough.

Rorschach’s journal is brilliant, damn it. It’s totally supposed to be over the top crank preposterousness, and succeeds admirably at that.

I’d put both Marston/Peter and Watchmen on a list of works of art I most love/have most influenced/entertained/moved me. and I do love Morrison’s Animal Man and Doom Patrol…I don’t know, these things are often somewhat individual, and I’m reluctant to say to anybody of anything, “You must read this!” I don’t even really think people have to read Shakespeare, which obviously is a lot more culturally central than any particular superhero comic. I do think there have been (a few) superhero comics I would call great art. But if someone is put off by the violence/sexism/stupidity of the genre, and never wanted to read anything in it, I wouldn’t argue with them too hard.

Grossman’s right and Krystal’s full of crap.

As for Rothman, I see where he’s going with the invocation of Frye, but the four forms Rothman cites are not especially relevant to current literature. However, in the ANATOMY Frye also elucidated four *mythoi”– which he termed the romance, the comedy, the tragedy, and the irony– that are far more applicable.

For instance, some critics might say that WATCHMEN is good because it skewers the traditions of the adventure-oriented superhero narrative, which in Fryean terms would be “romance.” But that view is simplistic. WATCHMEN is a good work within its own mythos, that of the “irony,” whose nature is to satirize and downgrade all forms of human experience, not just types of disreputable pop-fiction. If adventure-oriented superheroes are good, they are either good or bad according to the romantic parameters they follow– but not because they don’t have enough satirical shit in them.

“In fact, I predict we’ll find ourselves still orbiting the mimetic sun of psychological realism.”

It’s more like a binary star, and the people facing the other “sun” are the ones who like Borges more than Trollope.

I don’t think Frye had any difficulty naming the opposite of mimetic realism. In the ANATOMY he contrasts “versimilitude”– which is the reigning principle of the mimetic– with “myth.” And I quote:

“Our survey of fictional modes has also shown us that the mimetic tendency itself, the tendency to verisimilitude and accuracy of description, is one of two poles of literature. At the other pole is something that seems to be connected both with Aristotle’s word mythos and with the usual meaning of myth. That is, it is a tendency to tell a story which is in origin a story about characters who can do anything, and only gradually becomes attracted toward a tendency to tell a plausible or credible story.”

There have been defenders of “literary myth” in the humanities long before Frye, such as Andrew Lang. Their voices just weren’t as loud– hence, Gavaler’s description of modern criticism as being totally oriented upon verisimilitude/ mimeticism.

” If adventure-oriented superheroes are good, they are either good or bad according to the romantic parameters they follow.”

Heaven forbid we think about what art is doing as well as whether it jumps through whatever genre hoop you set up.

Gene, fantasy scholar Bryan Attebury notes that passage too, but as evidence of Frye’s not having a very clear idea of the other pole, “something that seems to be connected to” myth of two kinds. And I’d add that a character “who can do anything” is only a surface quality and only sometimes opposed to mimesis.

“Heaven forbid we think about what art is doing as well as whether it jumps through whatever genre hoop you set up.”

Whatever can be done well is worth doing, regardless of all other considerations.

“Gene, fantasy scholar Bryan Attebury notes that passage too, but as evidence of Frye’s not having a very clear idea of the other pole, “something that seems to be connected to” myth of two kinds. And I’d add that a character “who can do anything” is only a surface quality and only sometimes opposed to mimesis.”

I read Attebury’s FANTASY TRADITION some time ago and generally liked the book, but would have to refresh my memory to address his complaint about Frye.

I think Frye’s idea of myth in this regard is substantive, even if I’d phrase it differently. Obviously there are a lot of fantasy-characters that can’t do just *anything:* the fable of St. George, which serves Frye as one of his major references, involves a superhuman warrior and a dragon, but not a deity capable of doing anything. What I think he meant was that the god who can do anything is a necessary imaginative counterpole to the idea of mortals, whose lives are defined by limitations. Myth, like other forms of fantasy, is defined by the existence of characters or situations that are not limited to what we know.

Can you take perternatural presences and treat them as if they really existed; that is, with attention to mimetic detail? Sure, but that mimetic treatment is the actual surface quality. Mimeticism doesn’t mean very much in such cases, as against its use for things that exist now or have been recorded as belonging to verifiable history. Borges, for instance, openly satirizes the continuity of discursive logic in works like “Library of Babel.”

@gene phillips

Mass murder is sometimes done very well. Just saying…

My issue with Frye’s “myth” is that it is opposite to mimesis only (or primarily) along one axis, the physical but not really the psychological. So, say, Moore’s Miracleman is “myth” in terms of superpowers, but mimetic psychologically.

Graham,

Since we were speaking of art and literature, the “done very well” remark was being applied to that domain. In the real world, there are a lot of things that can be done well to ill effect.

But Chris, going by the results of your test of two stories with psychological realism, where only one possessed SF tropes, you reported that the SF tropes diminished the effect of the psychological realism, at least insofar as the test could measure it.

My terms are different than yours, and I still don’t think psychological realism can remain the focal point it once was. But I too have stated that mimetic qualities– which would include attention to the fine details of psychology– don’t have nearly the same effect on “perternatural presences” as they do upon circumstances that our society deems naturalistic.

Miracleman certainly isn’t only about psychological realism. Moore has stated that it was in part his attempt to exorcise the superhero demon from his soul. Since the hero’s execution of Gargunza in the first story-arc barely differs from the more ultra-violent acts of certain Golden Age heroes– I’d say that Moore’s exorcism was a spectacular failure.

True, SF tropes can kill literary reading, but that’s more about readers than texts. My students, after just a couple of weeks, had learned how to approach an SF text with literary fiction reading skills, so it’s not about the texts themselves.

Nice point about Miracleman–which, oddly, I was just reading today for another article. I think Moore makes explicit what golden age writers left unexplored but fully present.

Obviously, I think that the readers’ response– were it proved to be statistically normative across the board– would be a response to their expectations about the texts; that they don’t respond to tropes of psychological realism in fantastic narratives because such tropes were formed in response to naturalistic narrative considerations. The expectation that a superhero ought to have an outlook like that of Superman, rather than that of Joe Schmoe, is partly learned, partly a logical extrapolation of the material.

Speaking of which, one reason some critics don’t like Frye’s use of the term “myth” is that it’s truly polysemic. It’s not just a synonym for any form of fantasy, but it also related to the repeated– and hypothetically hardwired– patterns that fantasy-material is used for. “Content and form,” if you like.

Two thoughts after a long absence:

Chris, your discovery that what people get out of genre material is based on whether or not they approach it the same way they do more mimetic stories is revelatory for me. It explains reactions I never really understood. For example, my father generally prefers stories that take place in the real world — Westerns, war movies, true stories of adventure and survival, and many others. I like those things, too, but obviously not exclusively. He took my brother and I to see Star Wars (Episode IV) in 1977. He thought he was being a dutiful father and did not expect to enjoy the film. After a few minutes, he became absorbed in the characters and the plot — I think because it’s basically equivalent to a traditional western, once you’re past the space trappings. I’ve noticed that with other material I’ve put in front of him. If he can turn off his low expectations or (very mild) disdain for unrealistic stories, he may enjoy it, and if there is a deeper meaning to be had, he’ll absolutely receive the message. But he has to flip that switch. Of course, as with your students, it’s much easier for him now that I’ve subjected him to years of practice (sorry, Dad!). Without intending to be critical of my father or anyone else, I think many people have a kind of learned prejudice against non-mimetic material — a judgment before the facts are in that precludes seeing the whole truth, much less conducting a thorough evaluation.

Of course, I know others who would never give the material a chance at all. These people understand neither my fascination nor the current zeitgeist, although I think the current broad appeal of such material has some of them wondering what it is they’re missing.

I wonder if the converse is true: Would you find similar prejudices against highbrow material that prevent people from fully appreciating the humor, tension, or adventure therein? In other words, would people approach it with expectations that would hinder their full appreciation of it?

The second point will be less long-winded. As far as classification without genre goes, I think there is a good middle ground between the current arrangement at Barnes & Noble and organizing all fiction alphabetically by author’s last name. Why not a literary equivalent of the Music Genome Project? They could discover, based on my reading tastes, that while I don’t like all science fiction, I enjoy moralistic protagonists in morally ambiguous situations, grand conspiracies, political philosophy, and explorations of human behavior across multiple genres. Theory of Mind could be just one more criterion the system measures against.

“Would you find similar prejudices against highbrow material that prevent people from fully appreciating the humor, tension, or adventure therein? In other words, would people approach it with expectations that would hinder their full appreciation of it?”

Excellent research question. My cognitive psychologist collaborator is busy with other projects at the moment, but I’m hoping to woo him back to this work eventually. That question will be on my list.

The answer is yes.

I think the industry seems to be doing well enough with franchises, and that will probably continue for the forseeable future.

My current hope is that the superhero fad bottoms out and we start getting retreads of more recent television shows like The Wire and OITNB and so forth. It’ll still suck, but at least some more diverse actors will get work.

John Hennings: ““Would you find similar prejudices against highbrow material that prevent people from fully appreciating the humor, tension, or adventure therein?”

I can get a sense of what you might mean by “highbrow humor” and “highbrow tension,” but do you have an example of “highbrow adventure?” It’s not precisely an oxymoron, but it’s close.

The Odyssey, Daphnis and Chloe, The Golden Ass, Yvain, the Knight of the Lion, Gawain and the Green Knight, Orlando furioso, Byron’s Don Juan, Ruslan and Ludmila, Alice in Wonderland… should I keep going?

Highbrow didn’t always suck, you know.

And then there’s always that collection of short stories at the top of this post.

Yeah, but Dave Eggers sucks.

Thanks for your answer. For reasons I won’t go into, I wouldn’t deem anything but the Byron and the Pushkin works to relate in any way to the modern hierarchy between highbrow and lowbrow. Even then, I’d tend to relate both Byron and that particular Pushkin work to the “mythic domain” of literary fiction, not the domain dealing with the “psychological realism” Mr. Gavaler is apparently endorsing.

I’ll concede the possibility of arguing about the rest, but there is no way that Ariosto doesn’t count as highbrow.

As for examples with regard to which one can talk about “psychological realism” – well, first I’d say Byron’s Don Juan is an example itself, and so is Childe Harold, and then there are the other Don Juans (Molière and Mozart), The Charterhouse of Parma, Moby Dick – the point is, highbrow adventure might be an oddity in the 20th and early 21st centuries, but that’s a peculiarity of the time, not a peculiarity of adventure stories.

Without wanting to mind-read Gene, I take it that this was the important phrase in his comment: “the modern hierarchy” i.e. most of the works on that list appeared before there was even the concept of a lowbrow literary tradition, and therefore no concept of a highbrow one either. That was my thought too. For instance, if I’m reading this graph right, the literacy rate in Italy when Ariosto was writing was <20%.

That said, it's certainly true that in the 21C, Orlando Furioso is only read by hoity-toity highbrow types.

oops, here’s the link: http://ourworldindata.org/data/education-knowledge/literacy/

There was certainly a concept of prestigious art versus trivial diversions and vulgar entertainment in Renaissance Italy (and in the 2nd century Greek and Roman world, though admittedly novels like Daphnis and Chloe and The Golden Ass would have been seen as less prestigious than epic or lyric poetry). The literacy rate is beside the point. The educated elite wants easy reads too (then as now). If I’d mentioned Lazarillo de Tormes, we could again argue about whether that counts or not, but Orlando furioso was seen as a poem for connoisseurs from the beginning.

“here was certainly a concept of prestigious art versus trivial diversions and vulgar entertainment […] (and in the 2nd century Greek and Roman world)”

Well, yeah, I can definitely agree with that part. (Don’t know enough about Renaissance Italy to speak to that)

Possibly one source of confusion here is that on one hand John Hemmings seemed to be affirming Chris’ association of “highbrow material” with works of mimeticism and psychological realism, Graham is citing as “highbrow works” stories that were prestigious in spite of whether or not they emphasized mimeticism and psychological realism. I’m not saying that those qualities don’t appear to some extent in, say, DON JUAN, but that’s why I asked John H. the question about what “adventure tropes” were being overlooked or neglected. The main article lists a lot of modern works that cherry-pick genre-tropes for “high lit” fiction. But from my admittedly limited exposure to Chabon, Atwood, and even LeGuin, I’d say that the majority of them avoid even the piddling swordfights in DON JUAN.

Chris said:

‘Gene, fantasy scholar Bryan Attebury [sic] notes that passage too, but as evidence of Frye’s not having a very clear idea of the other pole, “something that seems to be connected to” myth of two kinds.’

I had assumed, Chris, that you meant this comment appeared in Brian Attebery’s THE FANTASY TRADITION IN AMERICAN LITERATURE, but since I’ve finally rec’d my library’s copy of same, I find that Attebery’s only mention of Frye in that book is a favorable one that has nothing to do with the topic addressed.

Where then did you read it? A google of the two authors got me nothing.

That’s from “Fantasy as Mode, Genre, Formula” (1992):”But the other end of the scale, the counterpoint to mimesis, is not so well established. Frye . . . even has trouble naming it. It is like myth, he says, but he has already used ‘mythic.” We need another term . . .”

OK, so even if he doesn’t like Frye’s term, Attebery’s with Frye in validating the idea of a continuum of “mimesis” and “myth,” rather than anything along the lines of the “solar mimesis theory.” Good to know; thanks for the response.

You bet. And (ouch) sorry about that “Attebury” typo.

No big deal about the typo. I see that the Attebery essay is part of a larger work and will be checking that out in future.