This post originally appeared on The Middle Spaces.

___________

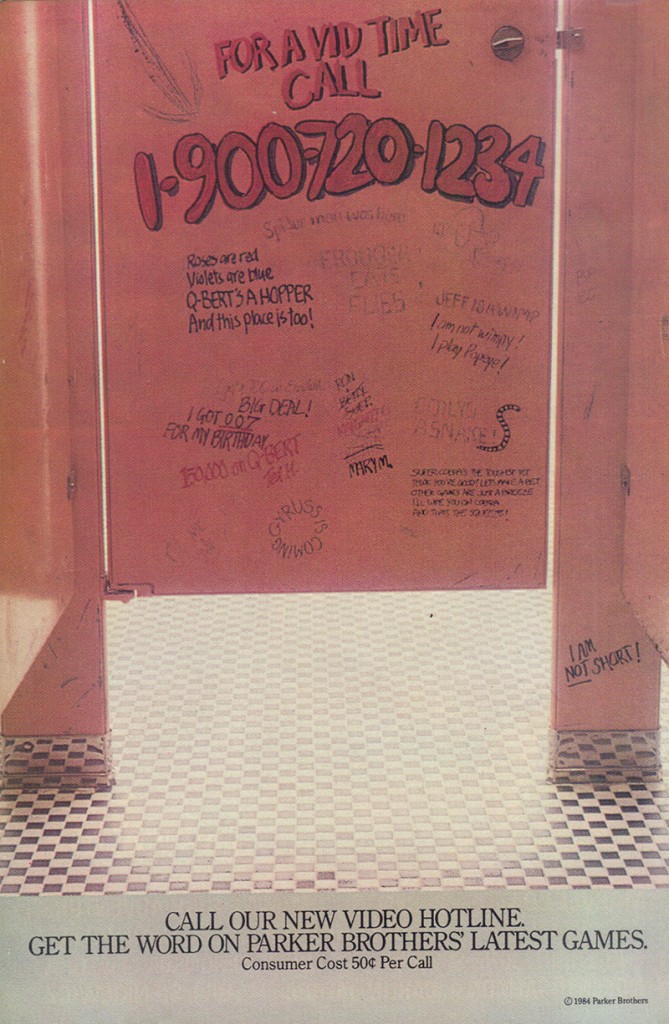

Long before the days of the internet and companies leveraging a fanbase willing to seek out commercials for their favorite properties and brands, TV spots and print ads were the only chance things had to catch on. By interrogating those old ads it is possible to uncover the strategies and cultural assumptions of those efforts to grab an audience. I recently came across an advertisement on the back cover of Power Pack #1 (1984) and it struck me as making an association that is simultaneously bizarre and prescient.

I remember the ad from my early teen years (I turned 13 the summer this comic came out), but I had never given much thought to what it offered and how it offered it. The ad is certainly slicker than most ads of the time. I am sure at the time it seemed like an extravagance. For 50 cents you could call a 900-number to learn about Parker Bros video games. My mom kept a strict eye on phone use in our house, and no attempts to use math to show her that regardless of how long I stayed on the phone, local calls cost a flat fee of 10.2 cents ever worked. Mami was wary of what seemed like confused and obscure systems that siphoned away money. I knew better than to risk an errant 50 cents showing up on the bill. But regardless of how strict (or not) moms might have been back in 1984, I can’t imagine that this effort by Parker Brothers video game division was very successful. I knew of no one who enthusiastically described a soon to be released game that they learned about by calling this hotline, or some strategy for Gyruss that had heretofore gone undiscovered. No kid even claimed that his “cousin” had called and learned some made-up-on the spot news about a new Star Wars game.

No. What is noteworthy about the advertisement itself, is not what it offered, but the banality of its fucked up normalizing of masculinist behavior to sell its products to kids.

The ad features the perspective of being inside a bathroom stall, with “For a Vid Time Call 1-900-720-1234.” Beneath it is a bunch of boastful video game-related graffiti. Instead of the usual puerile context of bathroom stall scrawl, we have a poem about Q-Bert, a drawing of a snake (a knowing phallic reference to the dongs common to bathroom stalls?), and some back and forth braggadocio about owning the James Bond 007 video game. Below the photo is some text ostensibly describing the service, but not really saying much—like calling a number you find in a bathroom stall, you never know what you’re gonna get.

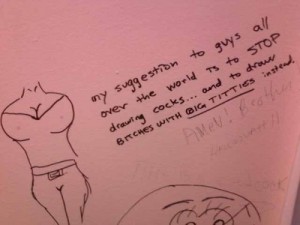

Common bathroom graffiti. Big boobs. No head!

Think about it for a second…This ad is asking young, presumably male, readers to associate calling this number with calling a number scrawled on the door of a bathroom stall. Consider how bathroom graffiti of this type is mostly used to shame women (this in both men’s and women’s restrooms), make homophobic claims about other men, and for boasts about hypersexual pursuits. Putting a woman’s phone number in a stall is the analog version of internet slut-shaming and abusive social media commentary. “I fucked Stacy in this stall” is meant to give the current crapper a vicarious thrill, the suggestion that they too could have a quickie in a public bathroom—as a man they are entitled to it. (Though my estimation is that those who write that shit in bathrooms are the losers of the sexual world, just as studies show that online gamer abusers are the losers of their world).

So for this advertisement to entice young men (and remember, comic readers at this time were still assumed to be boys between the ages of 8 and 14) with an allusion to the dirty side of sexual politics is just weird. Weirder still is that there was no objection to this idea being used to advertise these games (that I know of), perhaps because the feature never took off, but also in part because doing that shit is considered normal “boy” behavior. The ad’s direct association of a potential wealth of video game information with the sexual discourse of the public bathroom is speaking directly to a young male market that has already absorbed American culture’s obsession with virility and competition, and women’s place in that obsession. It is selling the 80s video game equivalent to Pick-Up Artist “culture,” with its email newsletters, seminars and books with “tips and tricks” for success. As reviews of the recent Adam Sandler film Pixels and its sad nostalgia remind us, in games ranging from Double Dragon to Cruisin’ USA, in the 80s the promise of a girl could be the prize of a video game (something the film makes a literal reality). (Actually, this hasn’t really changed at all, and you should check out Anita Sarkeesian’s Tropes vs. Women: Video Games for her excellent analysis of this in “Women as Reward“). Writing a woman’s number on a bathroom wall represents a sick double-valence: the possibility of an easy lay or the opportunity to spout uninvited salacious and/or abusive comments anonymously to a stranger.

So for this advertisement to entice young men (and remember, comic readers at this time were still assumed to be boys between the ages of 8 and 14) with an allusion to the dirty side of sexual politics is just weird. Weirder still is that there was no objection to this idea being used to advertise these games (that I know of), perhaps because the feature never took off, but also in part because doing that shit is considered normal “boy” behavior. The ad’s direct association of a potential wealth of video game information with the sexual discourse of the public bathroom is speaking directly to a young male market that has already absorbed American culture’s obsession with virility and competition, and women’s place in that obsession. It is selling the 80s video game equivalent to Pick-Up Artist “culture,” with its email newsletters, seminars and books with “tips and tricks” for success. As reviews of the recent Adam Sandler film Pixels and its sad nostalgia remind us, in games ranging from Double Dragon to Cruisin’ USA, in the 80s the promise of a girl could be the prize of a video game (something the film makes a literal reality). (Actually, this hasn’t really changed at all, and you should check out Anita Sarkeesian’s Tropes vs. Women: Video Games for her excellent analysis of this in “Women as Reward“). Writing a woman’s number on a bathroom wall represents a sick double-valence: the possibility of an easy lay or the opportunity to spout uninvited salacious and/or abusive comments anonymously to a stranger.

Given the association of video games with a male-dominated space hostile to women as early as 1984 then the negative reaction by a segment of male gamers to a critique of sexist tropes in video games and the impossible categories the games settings, plots and assumptions create for women in the games makes perfect sense. The reaction is an extension of that same frustrated entitlement that writes Stacy’s name and number in a public stall.

In other words, in a sort of obtuse way, this advertisement prefigures the attacks on Sarkeesian and “Gamergate” vitriol directed towards any woman that speaks up about this topic.

A strange mix of private/anonymous location (the stall or the seat in front of the game screen) and the public behavior that emerges from the discourse of those places, leads to the automatic id-driven lashing out at interlopers who “don’t understand.” Just as the comic ad promises access to special knowledge and thus video game success (leading to being a “real” or “hardcore” gamer), the cultural gate-keeping of the geek-o-sphere seeks to maintain an area of male power through leveraging media conspiracies (“it’s about ethics in journalism!”) and narratives of the “fake geek girl.” These, of course, are narratives constructed after the fact to make the abuse cohere with their self-image. Just like any other activity that becomes synecdoche for masculinity, maintaining a particular male video gaming in-group status appears predicated on treating women like shit (or condoning others doing so). This activity is reinforced as a “cultural” value virtually through game actions (women as prizes, women as props) and explicitly through abusive language and other online behavior (or even sometimes in person!). All the while, this attitude is exacerbated by an expectation that any women involved with video games must be sexually available to men. It seems about as healthy as trolling for dates in a bathroom stall.

I do want to pause for a moment, however, and make sure that I do not come off as being anti-graffiti. I love graffiti, have maintained a tumblr with graffiti on and off for a couple of years, and spent many a lunch hour at my old job wandering around lower Manhattan taking snapshots of stuff ranging from toy-ass tags to totally bombed out walls. Graffiti, even bathroom graffiti, can be wild and inventive, creative in ways that impress me more than a lot of contemporary art. Spend time going through a Google image search for “bathroom graffiti” (though that link comes with a possible trigger warning) and you’ll see it can be funny and just plain appealingly weird (like the weird and raunchy, but not necessarily sexist, “lobster cock”). There is something about its invisibility through its ubiquity and the palimpsest quality of years of going over each other that makes discovering it a thrill. Not all of it is in the tradition of “For a good time call…” or homophobic claims about the bartender. However, the particular context of the Parker Brothers ad connects their product to unwanted sexual solicitation and normalized notions of women’s sexuality and male entitlement. It was not simply jokey cartoons about poop or reminding us that Led Zeppelin Rocks!

I do want to pause for a moment, however, and make sure that I do not come off as being anti-graffiti. I love graffiti, have maintained a tumblr with graffiti on and off for a couple of years, and spent many a lunch hour at my old job wandering around lower Manhattan taking snapshots of stuff ranging from toy-ass tags to totally bombed out walls. Graffiti, even bathroom graffiti, can be wild and inventive, creative in ways that impress me more than a lot of contemporary art. Spend time going through a Google image search for “bathroom graffiti” (though that link comes with a possible trigger warning) and you’ll see it can be funny and just plain appealingly weird (like the weird and raunchy, but not necessarily sexist, “lobster cock”). There is something about its invisibility through its ubiquity and the palimpsest quality of years of going over each other that makes discovering it a thrill. Not all of it is in the tradition of “For a good time call…” or homophobic claims about the bartender. However, the particular context of the Parker Brothers ad connects their product to unwanted sexual solicitation and normalized notions of women’s sexuality and male entitlement. It was not simply jokey cartoons about poop or reminding us that Led Zeppelin Rocks!

Anyway, this is all to suggest that the ad is a signifier for the way masculinity is linked to presumably male-oriented (or at least the subject of male-focused marketing of) activities and thus makes the culture around those activities pretty insular. It’s synecdochal. The activity stands in for manhood and manhood for the activity, but you need only consider the arc of video games in our culture (from kiddy novelty or nerd-stuff to billion dollar movies and New York Times reviews) to understand the malleability of masculinity. Hard and fast ideas of what being a man means and what a man does are absurd. The very fluidity with which masculinity can be framed is a good thing though, because it also means there is a chance to imagine a masculinity that does not require an underbelly of anti-woman and homophobic ideals to exist. The pathologies of masculinity makes us suckers for capitalism. Advertisements like the Parker Brothers’ Video Hotline tap into young boys uncritical acceptance of patriarchal ideology to shill another layer of advertisement that they hope the consumer will pay for. But whether it flies or fails, ultimately we all pay for it in the ongoing reinforcement of toxic and unnecessary ideas of male entitlement.

Why wouldn’t the lobster cock artist change Corinthians to Crustaceans or something?

I remember being very confused by that ad.

Yes, that would have been clever. Or Crustathians.

I dunno .. if you had shown me the ad without the explanation, I would never had guessed what the story was.

I don’t think many people has thought of those “for a good time, call…” scribblings as slut shaming. The obvious bullshit part – the claim that “Suzy” wrote her phone number in the mens room because she wanted to meet guys – is so overwhelming, that that ‘Suzy’ mostly come off as a fictious character.

Maybe the people behind the ad didn’t give it much thought, either?

That said, I think you’re half right … and it is worth digging into why gaming has grown such a reactionary and extremistic fanbase.

Speaking of…I realized Sarkeesian got a bunch of direct threats and vitriol, but looking at the search results for “anita sarkeesian” and “feminist frequency”, the vast majority of the hits seem to be people saying Sarkeesian is somehow anti-feminist and damaging to women. Is this folded into GamerGate (I’m willfully betraying my naivete on the issue here) or is it some other group, like some TERFs, that seem to be making these “feminist” videos attacking Sarkeesian?

Kasper, of course the people behind the ad didn’t give it that much thought (at least I hope not), but more than likely just thought of it as “boys will be boys” kind of activity.

I am not sure what your point is with the second part. The fact there is a disassociation between a woman’s name/number and a real person is part of the problem that emerges from male entitlement having primacy.

Petar, not sure about your Google searches, b/c that is not my experience – but I do know some people have taken issue with Sarkeesian’s implicit attitude about sex workers that has come through in her videos – but that is the only critique of her feminism that I know of that is not obviously disingenuous (but I am sure there may be others)

I don’t think radical feminists have a problem with Sarkeesian. I’m sure gamergate has memes about how Sarkeesian is actually hurting women somehow, though. It’s not infrequent for anti-feminists to say that feminism is hurting women.

As Osvaldo says, the main good faith feminist criticism of Sarkeesian is that she seems to see sex workers as victims, or sex work as innately victimization. It’s a little uncertain what her position there is precisely, though; she’s been asked to clarify at various points and hasn’t.

I wrote about this issue here, fwiw.

Thanks for the reference Noah.

Don’t know if this adds anything, but just to illustrate, when I search “anita sarkeesian” verbatim on YouTube, I get a bunch of hits saying she’s lying, that she sucks at feminism (particularly because she think The Scythian in sword and sorcery is a positive female character), that she’s “busted,” whatever that means, and two videos with particularly absurd titles, those being “Reality v. Anita Sarkeesian” and “Female Entitlement by Anita Sarkeesian.” What’s odd is that the videos seem to be framed as if they are from a woman’s perspective, or actually made by women. I just wonder how many of those are Gamergaters posing as concerned feminists and how many are women from other groups or acting independently.