In Enid Blyton’s novels, the time is always now. The sense of a peculiarly British, unending vacation transforms the literary space, whether the preteen Find-Outers stay in idyllic Peterswood or whether their counterparts from the Adventure series investigate smugglers of dangerous MacGuffins in distant, colonial climes. Nobody ever changes, past events are referred to with the most perfunctory of allusions and the future does not extend beyond the case to be solved. An evildoer painted the Siamese Cat! The butler is a smuggler! She was him all along! While the range of plot options is attenuated, this now-time is the main appeal of these YA ur-texts. The compact is a simple one, dutifully commented on by the protagonists: now-time will contain a mystery, but more importantly it will feature exhaustively described picnics, antics by animal companions, denigrated sidekicks from lower classes and a perennial movement away from home. Adults fade into the background, functioning mainly as the assurance that the status quo will, ultimately, be assured as a paternal deus ex machina swoops in to give legitimacy to the feats of detecting already accomplished. “MOTHER, have you heard about our summer holidays yet?” asks the Famous Five’s Julian at the beginning of their first literary outing. Yes, Mother has heard. So have the readers. Everyone knows what to expect.

There is no coming-of-age in these novels. They present readers with something akin to heterochrony. With this, the French philosopher Foucault designates other time, which “functions at full capacity when men arrive at a sort of absolute break with their traditional time.” The terms of exchange for this break are simple: young readers do not expect the formula to progress, do not even (as the old defence of genre fiction would have it) expect a blues-like variation on a narrative standard. In Blytonland, readers demand to be released from time. Any break with now-time is swiftly passed by, anything that contains too much future has to be ignored. A protagonist’s assurance that they will all check in on the Indian helper figure in a couple of years is but a hitch in the suffocating comfort of a vacation that never ends.

When Stan Lee offers his own now-time for his expectant true believers, it comes with a well-known caveat: illusion of change. “Evolution, but 360 degrees’ worth. Same old Spider-Man, same old Peter Parker, same old problems at the core”, as Peter David puts it in the 1998 Comic Buyer’s Guide. Spider-Man will always return where he was. And why shouldn’t he? Why should we not grant Spidey and his readers the same now-time Blyton’s characters have been afforded with cosy abandon? After all, once readers catch on to the formula, they were expected to have already moved on to other cultural forms.

The current Marvel Behemoth (the company, not the character), however, will not allow us to abandon enthusiasm. Notably, the Disney-subsidiary has announced its filmic takeover as a succession of phases, a new one (Phase Three!) to receive its Cumberbatchian inauguration next year. And Spider-Man, too, has been recast for an intra-superheroic Civil Fistfight which will, once more, Change Everything. Now-time is dissolved in breathless development. This is not so much illusion of change as illusion of propulsion, of eternal growth, a movement from movie to movie and a universe steadily expanding from phase to phase. This self-replication is masked by dint of sheer forward momentum: How are we to notice that we are still in the same now-time, when we suddenly find our heroes in pursuit of magic (newly introduced to the shared universe) or, according to collective fingers-crossing, are finally graced with a celluloid superheroine? The films do not refute the recurrences of the same – it is half the fun. Critique is pre-empted by the movies themselves: the self-copying robot and the knowing, quippy subversion of tropes assure us that everyone is in on the joke. Corporation, fans, media – genre-savvily, we co-develop the illusion of change together. It is ours.

In contrast, Blyton’s heterochrony is a simple one. “’Ask her if we can go there!’” cries Famous Five’s Dick, “’I just feel as if it’s the right place somehow. It sounds sort of adventurous!’” It does and it will. The slightest twist of the plot-dynamic suffices. If there is an illusion of change, it is a flimsy one. That’s not what these texts and their perennial present are about. In a similarly straightforward way, comics used to embrace their stasis. Half the appeal of Silver-Age Superman is the staunch refusal of development: the details of the zany plot are less relevant than the fact that Lois, once more, tries to expose the Man of Steel’s secret identity. Jimmy has transformed into any number of other Jimmies and is dutifully restored. Superman had a son for a while, but he vanished. In genuine superheroic now-time, freed from illusions of change, reduplication in space replaces development in time.. Another Bizarro version. A superdog. A superhorse. Robotic doppelgangers. Krypton in a bottle. These are similar terms of exchange to the ones accepted by the Blyton-reader of yore: several groups of friends in several series. Remote places. Antagonists. Why should anything change? The next novel in the series is right there.

Foucault again: the role of heterochronies “is to create a space that is other, another real space, as perfect, as meticulous, as well arranged as ours is messy, ill constructed, and jumbled.” The best thing about this non-place of the now? We can leave it behind. Doomed planet, desperate scientists, last hope, kindly couple: at some point we have seen it all, repetitions and reduplications notwithstanding. After a decade of superheroic cultural hegemony, this movement outwards, away from now-time, towards other unique temporalities, is more difficult as we are invited to partake in a trans-medial illusion of change. Which character have we glimpsed in the new teaser? More after the jump. Consider yourself teased. A new phase is about to begin.

Unabashed heterochrony is a thing of the past. “Have you heard about our summer holidays yet?” We used to. And no one expected us to pretend otherwise. Now, instead, we are invited (Summer 2016!) to anticipate a new era, a perennial movement forward. This breathless anticipation effaces the ways in which it is, after all, still the same summer, the same vacation, the same radioactive spider. Conventions are not to be leisurely accepted and abandoned but celebrated as blatant now-time has been recast as coming-soon-time. Blyton’s eternal present, as smug, self-satisfied (and, not to forget, insufferably racist) as it seems today, was, at least, much easier dismissed.

Interesting – but is “coming-soon-time” essentially different from the old serials that lived by making you want to come back to see how the hero saves the day and reverts everything exactly the way it was this time?

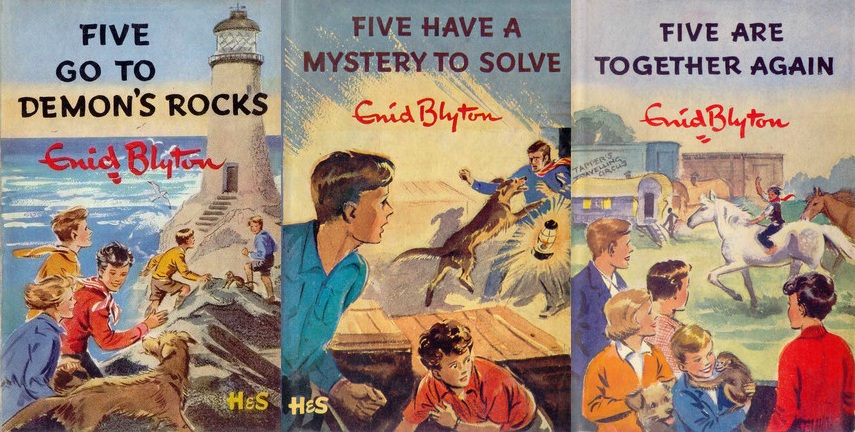

Side note: God help me, but I love those covers, demoniacally grinning white devils and all.

“coming-soon-time” is a perfect description of an odd feature of current superhero comics. Every big crossover ‘event’ is pitched as changing the shape of the Marvel/DC universe for years to come, but they’re years that never come. The only narrative pay-off ever seems to be setting up the next change of the shape of the etc. etc.

re Graham Clark: Sure, the constant anticipation is not a unique feature of the Marvel/Disney-method – but the co-production by fans and entertainment media may well be.

There is a parallel development of popular culture and academic discussions there. The scholarly narrative used to focus on production, standardization, commodities and, ultimately, ideology. From at least the 1980’s on, this is largely displaced by the cultural studies idea of active ‘consumers’ fashioning identities and giving meaning to their lives: these consumers (or more horribly: ‘prosumers’) give surprise twists to the way they use media, buy things and (as per coming-soon-time) co-create anticipation for new films. It seems to me that in this shift towards a positive, generative model of consumption, the underlying terms of the corporate world have both been forgotten and become more unavoidable.

That may be true even if the involvement involves important, worthwhile causes, such as increasing diversity: while the white power fantasy of superheroes has to be called out, lobbying for a Black Widow toy also aligns social progress with the progression of the franchise. One becomes almost literally invested in its success.

Enid Blyton and a lot of the older, massively popular YA-fiction showed much lower adaptability: it can be critiqued for its racism/sexism/classism but not as readily adapted. The Marvel movies, on the other hand, promise change towards more inclusion, progress, while extending the innate conservatism of superheroes from movie to movie.

But I agree with you, these tactics have existed before and they way they evolve will be interesting to watch.

Re Jones, one of the Jones boys: yes, the crossover structure of comics and they ways it has been adapted to other media is fascinating, especially its centrelessness and, again, the active co-creation of picking and choosing series and tie-ins. Would be interesting to look into precursors to the shared-universe-idea in YA-fiction; Blyton, for her part, did not allow for characters leaving their episodic bubbles.

I do like the covers, too. And the titles, especially the perfunctory “Five have a mystery to solve”.

Isn’t that unchanging now-time also typical of much adult popular fiction, notably many detective series?

Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple went down the decades with nary a change in their circumstances; so, too, did Nero Wolfe (at least until the very last book in the series.)

Adults feel the comfort of the familiar no less than children.

There was actually some continuity in the Poirot books (and I think in the Miss Marple too?) There are occasional references to past cases, and Curtains (the last one) actually kills Poirot off.

There was a bit of continuity in the Nero Wolfe books even before the last one. Archie met his girlfriend, who became a regular, in one of the books; a few recurring characters got killed off; and there were three books in which the criminal mastermind Arnold Zeck appeared, with the later books referring to the earlier ones.