Can reading detective fiction and Superman literature turn you into a supervillain? Super-lawyer Clarence Darrow says yes. He argued his case this week in 1924.

The facts were indisputable. His clients, Dickie Loeb and Babe Leopold rented a car, picked up Dickie’s fourteen-year-old cousin Bobby from school, and bludgeoned him with a chisel in the front seat. After stopping for sandwiches, they stripped the body, disfigured it with acid, and hid it below a railroad track. When they got home, they burnt their blood-spotted clothes and mailed the parents a ransom note. It was the perfect crime.

Dickie was nineteen, Babe twenty, but both had already completed undergraduate degrees and were enrolled in law schools. They were also both voracious readers. Darrow, their defense attorney, detailed Dickie’s literary tastes: “detective stories,” each one “a story of crime,” ones, he said, the state legislature had wisely “forbidden boys to read” for fear they would “produce criminal tendencies.” Dickie “devoured” them. “He read them day after day . . . and almost nothing else.”

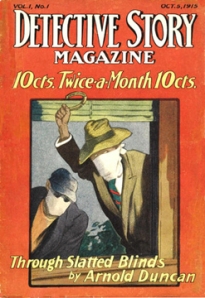

Darrow didn’t mention any titles, but Dickie must have snuck stacks of Detective Story Magazine past his governess. The Street and Smith pulp doubled from a bi-monthly to a weekly the year he turned twelve. Johnston McCulley was a favorite with fans. His gentleman criminal the Black Star wears a cape and hood with an emblem on the forehead. So does his Thunderbolt. Darrow said Dickie’s pulps “all show how smart the detective is, and where the criminal himself falls down.” But the detectives chasing the Man in Purple, the Picaroon, the Gray Ghost, the Joker, the Scarlet Fox—they never catch their man. Those noble vigilantes remain safely outside the law. They are also all young men born into wealth who disguise their secret lives. So Dickie, the son of a corporate vice-president, learned to play detective, “shadowing people on the street,” as he fantasized “being the head of a band of criminals.” “Early in his life,” said Darrow, Dickie “conceived the idea of that there could be a perfect crime,” one he could himself “plan and accomplish.”

Babe was an impressionable reader too. He’d started speaking at four months and earned genius level IQ scores. Darrow called him “a boy obsessed of learning,” but one without an “emotional life.” He makes him sound like a renegade android, “an intellectual machine going without balance and without a governor.” Where Dickie transgressed through pulp fiction, “Babe took to philosophy.” Instead of McCulley, Nietzsche started “obsessing” Babe at sixteen. Darrow called Nietzsche’s doctrine “a species of insanity,” one “holding that the intelligent man is beyond good and evil, that the laws for good and the laws for evil do not apply to those who approach the superman.” Babe summed up Nietzsche the same way in a letter to Dickie: “In formulating a superman he is, on account of certain superior qualities inherent in him, exempted from the ordinary laws which govern ordinary men.” A member of “the master class,” says Nietzsche himself, “may act to all of lower rank . . . as he pleases.” That includes murdering a fourteen-year-old neighbor as one “might kill a spider or a fly.”

So Babe considered Dickie a fellow superman. And Dickie considered Babe a perfect partner in crime. The two genres have one formula point in common: heroes are “above the law.” When Siegel and Shuster merged Beyond Good and Evil with Detective Story Magazine in 1938, they came up with Action Comics No. 1. Loeb and Leopold only got Life Plus 99 Years, the title of Babe’s autobiography. Prosecutors wanted to hear a death sentence, but Darrow wrote a modern law classic for his closing argument. It brought the judge to tears.

William Jennings Bryan liked it too. He quoted excerpts during the Scopes “Monkey” trial the following year. Bryan was prosecuting John Scopes for teaching the theory of evolution in a Tennessee high school, and Darrow was defending him. Scopes, a gym teacher subbing in science, used George William Hunter’s school board-approved Civil Biology, a standard textbook since 1914, and one that shocks my students when I assign it in my “Superheroes” course.

“If the stock of domesticated animals can be improved,” writes Hunter, “it is not unfair to ask if the health and vigor of the future generations of men and women on the earth might not be improved by applying to them the laws of selection.” After describing families of “parasites” who spread “disease, immorality, and crime,” he argues: “If such people were lower animals, we would probably kill them off to prevent them from spreading. Humanity will not allow this, but we do have the remedy of separating the sexes in asylums or other places and in various ways preventing intermarriage and the possibilities of perpetuating such a low and degenerate race.”

This was one of Bryan’s main objections to evolution, a term he used interchangeably with eugenics: “Its only program for man is scientific breeding, a system under which a few supposedly superior intellects, self-appointed, would direct the mating and the movements of the mass of mankind—an impossible system!”Bryan links eugenics to Nietzsche, as Darrow had the year before, saying Nietzsche believed “evolution was working toward the superman.” The claim is arguable, but the superman was “a damnable philosophy” to Bryan, a “flower that blooms on the stalk of evolution.”

“Would the State be blameless,” he asked, “if it permitted the universities under its control to be turned into training schools for murderers? When you get back to the root of this question, you will find that the Legislature not only had a right to protect the students from the evolutionary hypothesis, but was in duty bound to do so.”

Darrow declined to make a closing argument, preventing Bryan from making his before the judge too, so their final debate played out in newspapers. Either way, Darrow was talking from both ends of his ubermensch. “Loeb knew nothing of evolution or Nietzsche,” he told the Associated Press. “It is probable he never heard of either. But because Leopold had read Nietzsche, does that prove that this philosophy or education was responsible for the act of two crazy boys?”

Perhaps Darrow’s hypocrisy is an illustration of a superman only obeying his own laws. It didn’t matter though. Like Loeb and Leopold’s, Scopes’ guilt was never contested, and the court fined him $100 (later overturned on a technicality). That was 1925, the year the Fascist-inspired “super-criminal” Blackshirt joined Zorro and his merry band of pulp vigilantes, while Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf climbed the German best-seller list.

Superman was ascending.

To give Bryan his due, he was erroneously conflating the theory of evolution with Social Darwinism, a worldview that rightly horrified him.

Those textbook quotes are great. I always thought Bryan got a bad rap, but hadn’t realized the full noxiousness of the pro-evolution side in the Scopes trial.

Well, the Superman may have been ascending, but whatever you can say about Superman, no article, you can’t say he explicitly teaches that if you’re like him, then you have the right to kill people like flies. (You maybe have the right to kill petty criminals or crooked industrialists, but that’s because they ostensibly deserved it.)

Look, we all know Superman’s biography. In 1925 he was nobody. In the ’30s he was a rather ruthless warrior for the Popular Front. In the ’40s, like so many radicals, he made a truce with the establishment to fight Hitler. In the ’50s, his youthful indiscretions behind him, he became a well respected pillar of society. The ’60s were kind of confusing, because nobody really seemed to have a use for him any more, and his old friend Batman inexplicably started hanging out with some really weird people. In the ’70s everybody told him how much they’d missed him and it seemed like things might be going back to normal. Then the ’80s happened, and ever since, everybody seems to like Batman better, whom he can’t even talk to any more, because all that guy wants to talk about these days is how he should buy gold and something he calls the North American Union, and things are just more confusing than ever.

Superheroes are a product of American liberal democracy (or semi-democracy), which – leaving aside the question of whether it’s better than, or worse than, or equally as bad as fascist Italy or Nazi Germany – was and is, in any case, different from either, with its own specifc forms of oppression. Equating superheroes with fascism seems to me to be, optimistically, an impediment to understanding the actual social effects and implications of the genre, or, pessimistically, hackwork for the sake of some other, unnamed social model.

@Noah

Well and good, but in the end, which side (of the Scopes trial) are you on?

Now, if you want a fascist comic book hero – aesthetically superior, as far as I know, to any superhero comic of the time except maybe Wonder Woman – Tintin wasn’t quite yet ascending in 1925, but would be in half a decade.

But perhaps significantly, Tintin, unlike Superman or the Black Star, generally operates within the law.

Also: According to Wikipedia, the Black Star “does not commit murder, nor does he permit any of his gang to kill anyone.” That detail would seem to be relevant to this piece.

Chris has done a lot of research on the origins of superheroes (got a book coming out) even…I think he makes a lot of pretty clear connections with fascism over various posts. Among other things, Superman was pretty clearly inspired in part by the KKK. Vigilante violence in the name of law and order looks fairly fascist. The argument that thus and so deserved it makes it more fascist, not less; fascists pretty much always argue that the enemy deserved it (they were inspired by Nietzsche, but they perhaps fudged that bit.)

I think Superman, and superheroes in general, as anti-fascist fascism makes a lot of sense, personally. Not least because I don’t think US ideology and fasicst ideology are always so different in practice (the Captain America: Truth makes that point fairly well, I think.)

Re: the Scopes trial. I’d need to read more about it before I’d have a really thought through take. I in general find the narrative about the forces of science nobly doing battle against ignorance hard to swallow, though. (That goes for the Galileo hagiography as well.)

Certainly superheroes were inspired by the KKK, but the KKK isn’t fascism. Still less so individual vigilante justice.

Fascists weren’t inspired by Nietzsche. Anglophones who already hated Nietzsche were inspired to blame the fascists on him. (Leopold and Loeb were inspired by Leopold and Loeb – anomalous individual pathology is no use for discovering the causes of social pathology.)

Ayn Rand, on the other hand, was inspired by Nietzsche – which wouldn’t matter, except that she happened to strike a chord with so many Americans.

So in a sense, Clarence Darrow was correct: Germans can safely read Nietzsche, but combine him with the American mind and you get a small but not insignificant amount of an intensely noxious compound. Conversely, Americans seem able to listen to Wagner with relative safety. Germans on the other hand…

Hitler liked Nietzsche, I’m pretty sure. He was inspired by a lot of things. Including American racism. Which is why saying that vigilante racist thugs here were fascist is I think fairly defensible.

Hitler officially liked everything that met the criteria of being German, prestigious, old, and not Jewish.

Graham, I love your history of Superman (especially the 70s kiss and make up part). I was a little kid then and found Superman and all of DC embarrassing compared to (what my kid brain considered) the more realistic world of Marvel.

If you’re interested in the relationship between fascism and superheroes (especially Superman), I have an article coming out on the topic in the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics. In short, I argue that superheroes have a direct relationship to historical fascism (as opposed to simply having fascist-like qualities, which is usually what’s meant when someone calls a superhero “fascist”). Because democracy was under threat by fascism, superheroes became popular as fascist-fighting fascists. They used fascist strategies (violence, anti-democratic authority, etc.) to protect democracy, which makes for a bizarrely self-contradictory character type (and might also explains why, as soon as Germany began to shift to a defensive military position, superhero comics began to decline in sales).

I’ll email you a copy if you like. By odd coincidence, this afternoon I’m appearing on Danny Fingeroth’s “1940” panel at Wizard con in Pittsburgh, so I’ll be talking more on this very soon!

The problem I see with this is that extra-legal violence isn’t the same thing as fascism. Fascism implies, first of all, the intention not merely to circumvent democratic government, but to take over the government, which superheroes don’t want to do, nor are superheroes even nominally all subordinate to one political party.

In those respects the KKK of the 1860s and 1870s had more in common with fascism, but even in that case the Klansmens’ ideal for society was very different from Mussolini’s or Hitler’s. In fascism, everybody submits to party discipline for the sake of a collective undertaking. In absolute contrast, the Confederacy and the KKK had a horror of central authority, accepting its existence at all only to the degree they considered necessary in order to protect the individual slaveowner’s right to do whatever he wanted to hit slaves (later, the individual landlord’s right to do whatever he wanted to his tenants, the individual boss’ right to do whatever he wanted to his employees, and the individual white man’s right to do whatever he wanted to black people).

If superheroes have something to tell us about any kind of oppression, then even more than the KKK, I would say it’s things like the Ludlow massacre: Initiated by private wealth and largely carried out by private agents. (Maybe Batman is more archetypal than Superman after all. At least, in spite of Superman’s origins, the default for superheroes ended up being to go after petty criminals more than corrupt mine owners.) Or, for that matter, George Zimmerman (notice how superheroes often attach themselves to one city – that is, an only somewhat bigger version of a neighborhood watch).

I don’t think it does. Or rather, I think that when superheroes represent oppression, it’s generally a kind of oppression different from fascism, and thus quite compatible with anti-fascism.

That is interesting. (I guess that means circa early November, 1942?) Though, if you don’t mention it in the paper, I’d also be interested in knowing:

– Declining at what rate, over how long a period of time? (i.e. Does this go directly into the post-war decline that’s been attributed to the advent of television?)

– What were movie ticket and book sales doing at the same time?

In any case, thank you, I would love to read that article! Either this is just my computer illiteracy manifesting itself again or Noah’s the only one who can see all our email addresses here, so in the event of the latter, mine is graham.c.clark@gmail.com

Also: Good luck at the panel!

The theory of evolution was in an odd place c. 1925. On the one hand, the fact of common descent — that all life on earth is derived from a common ancestor — was, I think, more or less universally accepted by serious biologists. On the other hand, the mechanism driving evolution was in serious dispute; and, in particular, there was much debate about the role of natural selection, which of course Darwin had so emphasised. The rediscovery of Mendel around 1900, and subsequent groundbreaking work in genetics in 1910s, was widely seen as inconsistent with the kind of gradualism favoured by Darwin and natural historians more broadly. A couple of population geneticists had started to show how genetics could be reconciled with natural history, but it took a while for their work to become generally influential

So it wouldn’t have been crazy, around that time, to think that “Darwinism” as a scientific theory was in trouble — although I don’t know how much of this dispute had percolated into general consciousness, and so whether Bryan would have actually been aware of it. (My guess is: probably not) (Also, much like modern “debates” about “intelligent” design, the legitimate scientific dispute wasn’t about the fact of common descent — but that’s all the creationists actually care about)

“Hitler officially liked everything that met the criteria of being German, prestigious, old, and not Jewish.”

Even someone who said that everything good about German culture was just stolen from the French and only had anti-Jewishness edited in his writing by his sister.

” In absolute contrast, the Confederacy and the KKK had a horror of central authority”

That’s not really true. The Confederacy’s ideological antipathy to central authority has been vastly overstated. The first plan of the south was to get the federal government to back them up and impose slavery everywhere. They only moved to states’ rights because they weren’t able to do that. Same with the KKK. Their real commitment was to racism, not to any particular government system. That’s really true of fascism too; it’s not like the Nazis were particularly enthusiastic about government authority they disagreed with.

Superhero comics sales basically declines forever, I think. But yeah, a lot of that was due to television going forward (it’s often attributed to Wertham, but Bart Beaty argues I think convincingly that television was the real culprit.)

This is so profoundly wrong that – genuinely sorry, but there’s no nice way to say this – I’m almost certain it’s concealing some kind of agenda.

The Confederate constitution banned the national government from spending money on infrastructure (the only exceptions being buoys, lighthouses, and harbors) and from supporting industry by subsidies or tariffs. (And nobody knows it! “Overstated” indeed.)

The slave state elite’s opposition to central authority was there from their inception. The reason our capital is in Washington instead of Philadelphia is because that’s what Alexander Hamilton had to give the slave states in exchange for their agreeing to the establishment of a national bank (which Andrew Jackson subsequently abolished anyway).

Of course, after thinking about the above comment for twenty minutes before posting it, the following occurs to me immediately after I do: Maybe all you mean is that the slave states seceded because they thought it was the only way to preserve slavery, and for no other reason – which is of course correct. If so, I’m half sorry for the tone of the above; only half, because you’re still downplaying the slave state elite’s pathological anti-statism and it’s result – keeping the masses defenseless against local members of the elite – both of which very much survive to the present day.

I thought Noah’s comment was just a statement of what is now conventional wisdom on the left about states-rights-ism: that it’s a fig leaf for racism and/or other prejudice. (That’s certainly how the analogue has been occasionally deployed in Australia — the main incident I can remember it in recent years was to let Tasmania keep anti-gay legislation on the books).

Not saying this to dismiss Noah’s point, just to say that it’s a very common sentiment on the left, or at least I thought it was.

Whether it’s exactly what Noah was saying or not, that is indeed a conventional wisdom on the American left – though unfortunately in what it leaves out as well as in what it says.

More comprehensive, of course, would be to say that states’ rights is a fig leaf for racism, prejudice, and economic oppression – or, to put in another way, for the preservation of the decentralized forms of power that certain groups (rich people, white people, men) currently hold.

I just can’t buy the argument that fascism’s real commitment is to racism and not to a government system. After all, fascism is a system of governance. Moreover, as important as racism was to the Nazi ideology and to Hitler’s ascent, it’s not necessary to fascism.

Yeah…I still don’t really buy it Graham. The rabid antipathy to central government is because the central government was seen as a threat to slavery, not the other way around.

And you seem to be saying (?) that decentralization supports inequity. Which is sometimes true. But (as fascism shows) centralized government can just as easily support authoritarianism.

Nate, I just read this three volume history of the Nazi party, and I was really surprised at how central the anti-Semitism actually was. I think it precedes the governance system, or is inseparable from it. Hitler’s push for rule by unitary dipshit was a recation to his view that the old governments were too weak to resist treasonous anti-Semites (basically.) The fear and paranoia around Jews were inseparable from the argument for undemocratic government.

I think that’s generally the case with authoritarianism, though the threatening other varies. I think for non-racist fascism, it’s often Communism that’s the bugaboo (Hitler hated the communists too, of course.)

Graham, do you have a reference re the anti-centralization of the South? I’m skeptical, but I could be convinced; would be interested to read more about it, anyway.

I acknowledged the centrality of anti-semitism to the Nazis. I just disagree that racism necessary to fascism, and even if it was, fascism would still be a distinct system of government.

It depends on how you’re thinking of fascism, I think. Qua abstract theory of government, it is indeed independent of racism.

But if you’re thinking of actual fascist regimes, it might be true that racism has been a crucial part of the motivation for/structure of all fascist regimes that have actually existed. (I’m no historian, so I couldn’t say). You might even extend this idea to the claim that racism (or oppression more broadly) is the only plausible motivation for any fascist regimes, as a matter of psychology and sociology. (Similar to how Corey Robin, I gather, has said that anxiety about losing privilege is the universal theme underlying different conservative movements)

Anti-Semitism was absolutely essential to Nazism, but demonstrably not essential to fascism, e.g. fascist Italy before about 1935, Francoist Spain.

re southern anti-statism, see Michael Lind’s Made in Texas: George W. Bush and the Southern Takeover of America (less topical than the title suggest) and Land of Promise and David Hackett Fischer’s Albion’s Seed.

For a partial distilled version: http://www.salon.com/2013/02/19/southern_poverty_pimps/

@Noah

I forgot to answer this part:

The point is that oppression can be centralized or decentralized, that America it’s often the latter, and that the one phenomenon shouldn’t be confused with the other.

Qualifier:

Partly yes, but also important (maybe less, maybe more) was the memory of the socialists overthrowing the old empire in November 1918 and surrendering to the Allies instead of fighting to the last man. So he made sure that didn’t happen in the next war.

Socialism and racism weren’t entirely separable for Hitler. I think communism in many fascist regimes is essentially racialized (I’ve seen interesting arguments about this in regard to the Indonesian genocide especially.)

I think oppression in the US is often decentralized…and then it’s often centralized. Both traditions in the US are thoroughly racist, imo, which is why any liberation effort in this country needs to be anti-racist first, rather than based in statism or anti-statism.

You might as well say both “traditions” (I’d say “phenomena”) are thoroughly classist.

There’s no such thing as an effort based in statism.

“Socialism and racism weren’t entirely separable for Hitler” – True, of course, but I don’t see the continuity between this and the comments you’re replying to – are you saying Hitler only objected to the 1918 socialist revolution and surrender because he thought the Jews did it?

Wow. This was a heavier discussion the one at my 1940 panel yesterday! The panel went well, but we didn’t have time to delve so far into these specifics. I just sent Graham my essay, but I’ll add two points here:

The decline in superheroes is best shown in contrast to other genres of comics, which continued to do well or even better. I think that undermines the claim that TV killed superheroes.

And the other tricky issue is the definition of fascism. This is where discussions tend to get derailed because participants aren’t really talking about the same thing. So, for instance, I don’t address the issue of a single, centralized government, which Graham in a comment above saw as key to fascism. I think superheroes still are clearly influenced by fascism though, whether they enact every quality of the larger agenda.

Jones, you make a good point about the difference between fascism as a theory of government and fascism in practice, but I think it’s important to remember that even if racism is a necessary condition of fascism, it’s not sufficient. Ironically (given the current conversation), the Confederacy proves the point.

The Confederate constitution is pretty similar to the original U.S. Constitution but for its notable and noxious protections for slavery. And for the Confederate political ideology, it too was pretty similar to the political ideology of the U.S. That is, there was a split between those who advocated states’ rights and those who saw a bigger role for the federal government. This suggests that had the South won, the result would have been a hodgepodge of liberal individualism and civic republicanism and not a proto-fascist regime. In other words, it would have been a de jure racist democracy (as opposed to a defacto racist democracy).

Chris,

I realize you’ve noted this before, but how are you defining fascism?

“There’s no such thing as an effort based in statism.”

??? I don’t understand what this means? There are lots of state sanctioned oppressions. The carceral state is the big one at the moment.

Hitler seems to have thought the Jews were responsible for the socialist revoluiton, right? It’s the Jews that stabbed Germany in the back, through socialist revolution and other nefarious means.

Nate, the thing is, is it a democracy when it’s run as a giant prison camp? For black people, the pre Civil War south looks a lot more like an authoritarian state than it does like Democracy.

You guys know that the Scopes trial was a setup, right? A local booster committee wanted to challenge the law (and get a lot of free publicity for the town) and Scopes volunteered – they saw to it he was arrested and charged. -That’s how a high-power celebrity attorney like Darrow got brought in; the substitute teacher wasn’t the one paying.

I never heard the eugenics brought into that, but given the tenor of the times, it shouldn’t surprise.

—

It might be fair to say that xenophobia is inherent to true Fascism – it comes with the definitely-inherent nationalism. Mussolini certainly had some racism going in there, but was really about Italy, restoring Italy’s glory, purging Italy of un-Italian otherness Holding Italy Down. Racism is almost always front and center, being a convenient brand of otherness to rail against — but for a recent close example, the sins of the Cheney Bund in the US are as stars in the sky or grains of sand on the beach, but the racism is hardly the first you’d think of unless you had to be an Arab-American (or any sort of brownish Muslim) in those fun years.

Fascism hates the other, always, and lives on scapegoating, always; I’d suggest the racism naturally follows, but is a symptom, not a cause.

– I meant that nobody says “We need a bigger state” without having a particular kind of state in mind (communist, fascist, monarchical), as libertarians say “We need a smaller state” – which is the only thing I can understand “based in statism or anti-statism” to mean.

– Yes, Hitler thought the Jews were responsible for the socialist revolution. The point is he hated both.

– Whatever you call the Confederacy, or for that matter the post-Reconstruction former slave state regimes, the point is they functioned very differently from the fascist states. It’s not question of moral evaluation, but of understanding the nature of the thing you want to destroy.

They functioned differently in some ways and similarly in others, I’d say. Focusing just on the differences leaves you with a partial understanding.

Oh, and thanks for clarifying; that makes sense.

“Nate, the thing is, is it a democracy when it’s run as a giant prison camp?”

Sadly, I’d say the answer is yes. Greek democracy ran on slave labor, and it excluded whole groups of people from the public sphere. However, it was the political system on which our democracy was based (in part).

The thing is, over the years fascism has become a Devil-term and democracy as God-term, where the former is a bludgeon used to denounce a wide variety of political regimes and behaviors and the former is posited as its opposite and a good in-and-of-itself. The problem is that this strips both concepts of their specificity and blinds us to what’s really going on in a particular historical instance.

I’d add that I do think the Confederacy had much in common with fascism, especially in its rejection of progressive values, commitment to hierarchy and a romantic (and largely fictional) vision of history. And there’s plenty to explore there, especially if we’re talking superheroes and the KKK (which to a large extent held onto a confederate worldview). In other words, I’m looking forward to Chris’s book!

Sorry to keep adding, but I was thinking about the democratic prison state question and it struck me that given the sheer number of people incarcerated we’re uncomfortably close to such an outcome, and that could lead us into something closer to fascism than to democracy. The thing is, we still have checks on the Federal government (the legislative and judicial branches, regular and mostly open elections). As such, we are, as a nation, in a position to fix the situation in a way that we wouldn’t were this a fascist state. Am I optimistic about this? Not really. But if I say the current situation is tantamount to fascism then I’m altogether discounting the possibility of civic action, which would get me off the hook from doing anything short of fomenting revolution.

Nate, I’ve been trying to coin a term for Robber Baron quasi-fascism with a little teeth, and generated a flag-background bumper sticker meme image with the slogan “Love America, Love its Constitution -They’re a package deal, knuckleheads”, but haven’t had a lot of luck with spreading it on Facebook so far.

Names and Ideas have power; I figure that’s what I can do about the current situation. Maybe.

“Is it a democracy if its run as a prison camp?”

Depends who you are.

But all the same, its reasonable forNoah to think of groups like the KKK as fascist. Because fascism isn’t particularly systematic, and can’t really be understood by taking its ideological claims at face value.

Anyway, Chris Gavaler – interesting post. Thanks

@BU

Is “plutocracy” not adequate (or “oligarchy” – the former for the robber barons, the latter for the southern big landowners)?

I hope America and the constitution aren’t a package deal – the constitution gives us the undemocratic absurdity that is the U.S. senate.

@sean

Fascist governments may not be systematic, but they are rigorous, which is exactly what the KKK wanted government not to be.

I don’t know that the KKK had an especial view of government as rigorous or otherwise. The mostly wanted white people in positions of power. Birth of a Nation (which I saw recently) is actually remarkably *pro* union. Lincoln comes off as a hero, for example. The main ideological commitment is to white unity against black people.

Plutocracy doesn’t include the suggestion of racism, is I think why it doesn’t work quite the same.

– The KKK existed to take away political power from black people, but the people who constituted the KKK had definite beliefs about what kind of government they wanted in other respects and what kind they didn’t.

Here’s a typically magnificent piece by Eileen Jones that quotes a hilarious bit of proto-libertarian self pity from Jesse James, who wasn’t a Klansman but might as well have been: http://exiledonline.com/rat-bastard-jesse-james-and-a-new-film-genre-“the-southern”/

– Lincoln is a hero in Birth of a Nation because he’s the one exception on the Union side, so when he’s assassinated, the south is at the mercy of Thaddeus Stevens (or rather, the tragic mulatto mistress who’s pulling Stevens’ strings).

– Well, Robber Barons also happened in parts of America where there were almost nothing but white British Protestants at the time (and still do – see the West Virginia mining country). And yes, of course, you can argue that racism was and is still a factor in those cases too, but on the other hand it isn’t.

Spent the day on the road, so am jumping in late again, but, since Nate asked about the definition of fascism I’m using:

“Nazism and Fascism, while historically, geographically, and ideologically separable, were both dictatorial, anti-democratic, totalitarian, nationalistic, and militaristic. The terms were often used interchangeably during the forties. The 1945 Time article “Are Comics Fascist?,” rather than excluding Nazism, uses fascism as a generic term that includes both German Nazis and Italian Fascists. Since Fascism and Nazism shared a mostly undifferentiated impact on the popular productions of comic books, this article continues the practice of referencing Nazism as a sub-category of fascism. In this more general sense, fascism, like superheroism, champion acts of anti-democratically authoritarian violence committed in the name of the national good.”

It’s not perfect, but I think it works.

That’s not exactly true re: Lincoln. Thaddeus Stevens is a good guy too; he’s just misled. And his family are heroic/lovable, if a little confused about the truly evil nature of black people. The film is really not about refighting the civil war; it’s about creating a post-war consensus around racism. That consensus absolutely includes federal acquiescence, and even federal enforcement. It’s just not an anti-centralization or anti-government film. (There’s a quote from Woodrow Wilson at the beginning of most prints, you know?)

And re Robber Barons, that’s the thing about plutocracy, which is arguably different from what happened in the South.

Works for me.

—

Oligarchy and Plutocracy are helpful suggestions for the vocabulary of what I’m thinking about, Graham, and I’ll definitely throw them into a conversation we’re having about it on my forum, but – teeth; visceral kick is something it needs, and I doubt the people I want most to reach know their history well enough to even get much out of Robber Baron.

I’m trying to sloganeer, not dissert.

You got me on the package deal -and the representation by state in the Senate is hardly the thing I think of first when contemplating What’s Regrettable In The Constitution (that would be the Electoral College, with the Second Amendment a close second)- but again, sloganeering. I’m trying to find a way to talk to the ‘conservatives’ (social conservatives who are actually statist) in their own language (w/o stooping near so low) and iconography. I’ll email Noah the bumper sticker image…

Chris,

I can’t disagree with your definition. That said, “authoritarian, anti-democratic and totalitarian” seems to entail a pretty specific kind of government, so I’m nit sure why you wrote that you don’t address the notion of a centralized state (maybe you just meant you don’t address it in this post).

Your point that the term fascism was fuzzy even during WWII is spot-on, and I can see how you would see the KKK as having fascist ambitions under that definition given its fixation on white nationalism. I’m still a bit skeptical of your claim about WWII superheroes (I’m not that familiar with the interwar superhero so I can’t comment on that). My primary reservation has to do with the fact that I don’t think the idea of a physically and mentally gifted individual saving the nation is at odds with the American democratic tradition so much as it is typical of the tension between individual and community in a liberal-democratic society.

If I recall correctly the “Are Comics Fascist” article, the working definition of fascism there hewed to the Freudian take on fascism… People like Fromm and Reich who sought to diagnose it as though a condition. On this view, almost any power fantasy counts toward a society’s final rating on the F-Scale, which I don’t really buy.

Yeah…just to throw in a mild dissent from the idea that the Senate is somehow innately undemocratic. I don’t think that’s really true. Once you’ve signed onto the idea that representative institutions are democratic, it’s not exactly clear why population would be moreso than state, or vice versa.

@Noah

– Nobody said Birth of a Nation is anti-centralization or anti-government (though if you’re saying it’s pro-centralization or pro-government, it isn’t that either).

– Yeah, the Unionists are good but confused – because they don’t agree with the ex-Confederates about black people, and then when they learn the ex-Confederates were right, we have our Satanic happy ending.

– A person in Wyoming has 66 times more votes than a person in California. It’s perfectly clear why that’s undemocratic. Less clear is why you would say it isn’t.

@BU

– Well, Mark Ames calls them vampires. Not sure if that’s any better for your purposes, but I do think it has a certain kick.

It does, it does. Not quite what I’m looking for (Cannibal LitchKing Zombielords would be closer, if way too long ;)- but helpful. [chuckles]

It’s not actually clear why having everybody’s votes count the same is “more democratic.” House votes are often badly skewed for lots of reasons. There’s no one good way to ensure representation; the US version is to have multiple representatives elected by multiple formulas. Is that “less democratic” than the British way, where there’s on institution with everybody having a single way of being represented? Not necessarily. I think your definition of “democratic” seem naive and undertheorized, basically.

Now, Washington DC residents actually don’t have representation in important legislative bodies at all. I think that’s much closer to being undemocratic and unjust.

For instance, currently House seats lean republican not so much because of Gerrymandering, but because democratic leaning districts tend to be urban, and majorities for democrats are very high; there’s essentially a huge amount of wasted democratic votes in the US at the moment. Is that unjust? How would you rectify it? There are systems (like, apportioning house representatives by the entire state) but then you lose local representation, and the areas with the largest populations would elect everyone, which isn’t an ideal solution either, for lots of reasons, especially in a country with a long history of marginalizing certain groups.

I would agree with the proposition that BOTH houses have far-less-than-ideal selective setups…

– This is even stranger than before. Yes, rural voters are overrepresented in the House – and vastly more so in the Senate. What axe are you trying to grind here, Noah?

– “Undertheorized” is always code for “Not drawing the conclusion my agenda requires.”

What is your agenda, Noah? Now I want to know, too.

Look everybody, it’s funny because he said the same thing I did but didn’t mean it.

I don’t think Noah has a particular agenda here, Graham, other than to argue for the sake of arguing. I’m with you — disproportionate representation is, ceteris paribus, undemocratic

I don’t think Noah argues for the sake of arguing.

What would a plausible agenda even look like here?

Hah; “undertheorized” is code for, “I don’t think you’ve thought this through sufficiently. Also, pffft!”

I’m not arguing for the sake of arguing! Though I probably do sometimes. I don’t know; I’ve been influenced on this by Jonathan Bernstein here, I think, who is a political scientist I admire a lot. I guess my agenda is more or less what I said it was; I think that representational democracy is always going to be an approximate game, and so it doesn’t really make a lot of sense to necessarily call one way of cutting things illegitimate. I also think that there’s a legitimate concern about regional groups getting overpowered through numbers; the House and Senate are meant to try to balance different interests. I don’t know that that’s a bad thing.

There have been changes in the way the Senate is set up; I’m much happier with direct election there than with having state legislators pick, and I’d be even happier as I said if DC got representation (and Puerto Rico, for that matter.) and I’d like to do away with the filibuster, probably (though I’m not entirely confident that that would ultimately end up better.)

But…well, I think working towards some purist view of direct election democracy can lead bad places sometimes (like to elections of local officials who really shouldn’t be elected, or to California’s ballot initiatives, which are a huge mess.) Ethanol subsidies are horrible policy, and they’re a direct reflection of the rural bias in the Senate. I wouldn’t say, “this is perfect” but I think saying it’s undemocratic is confused about how representative democracy works in ways which can lead bad places, too.

Not sure that’s plausible, but it’s what I’ve got!

– 66 votes to 1 isn’t approximate

– ‘I also think that there’s a legitimate concern about regional groups getting overpowered through numbers; the House and Senate are meant to try to balance different interests. I don’t know that that’s a bad thing.’ Meaning you think it’s a good thing.

– “Shouldn’t be elected” according to whom?

– California’s ballot initiatives are a bogeyman. Compared to other states, or even just other rich states, or other rich liberal states, California doesn’t stand out as particularly inefficient or perverse.

Why do you assume that I mean something different than what I say? When I say I don’t think it’s a bad thing, that’s what I mean. I’m not sure it’s good. There could be better methods. But is it worth putting a vast effort in to change it rather than working on other issues? I’m not convinced. (And when you say, “this is undemocratic”, that suggests it’s illegitimate, and therefore a major priority.)

I think elections of low level officials (like county clerks) are a waste of money, and are also bad in terms of being able to hold people accountable. There’s generally not enough info about the canddiates for voters to know if they should stay on one way or another. Once you’re in, it’s just very difficult to remove you. Better to have appointments by people who the voters will actually blame/remove if things go poorly.

I’ve talked to fairly knowledgeable folks who think California’s ballot initiatives are a serious mess. I guess you could convince me otherwise, but I’m not inclined to just take your word on it.

– You’re a good critic. You know nobody ever means what they say.

– Particularly since we’ve been throwing around the word authoritarian so much in this comment section, let’s note that giving the power to appoint officials to other officials rather than to the electorate is authoritarian – more so if the appointments don’t have to be renewed after every election (do you have a preference there?).

– A lot of things are a serious mess. Ask the knowledgable folks to convince you that California’s outcomes are worse than other states’.

It’s not more authoritarian to have water commissioners appointed rather than elected, any more than it’s authoritarian to have cabinet members or judges appointed. “The KKK isn’t authoritarian — but appointing water commissioners is dangerous!” Come on.

So, lots of states have gotten to a giant mess in various ways. California’s gotten there by ballot initiative. Just because you could get there different ways, that’s not a sign that the ballot initiative was somehow not a screw up.

Or let me put it this way. Illinois is a disaster because it didn’t pay its pension obligations for 40 years. Other big wealthy states are in bad shape too! Therefore, not paying the pension obligations wasn’t actually a mistake. Or…possibly that logic doesn’t work.

– Yes, appointing cabinet members and judges is authoritarian too.

– The KKK was for white authority over black people. More generally, the people who constituted the KKK were for white authority over black people, rich white authority over poor white people, and nobody’s authority over rich white people – which they got – maybe as bad as the Nazis, maybe not, but in any case different from the Nazis, who were for the Nazi party’s authority over everybody and Hitler’s authority over the Nazi party.

– If the result is no worse than with any other method (and better than many)…

– You switched from talking about form of government to specific policy. If you want to argue that Illinois doesn’t have the best political system and should switch to California’s, well, okay!

What exactly is the point of saying that appointment of judges is authoritarian? You’re just convincing me that I’m right about the Senate; you start from there and you slide right into some sort of preposterous linkage of appointments to actual anti-democratic regimes. That’s just silliness. A system doesn’t become authoritarian because every single person isn’t elected. If the President hires a secretary, that’s authoritarian? Teachers at the military academies should be elected? Any official who isn’t elected is on a slippery slope to authoritarianism?

The whole point of representative democracy is that you have representatives, who make some decisions. Among those decisions are appointing and hiring other staffers and officials. If you think representative democracy is illegitimate, just say so; stop shilly-shallying about Senators and dog catchers.

There’s too much political science in this thread for me to engage without feeling like I’m at work, but I have to promote the research of one of my students, since it is relevant to the discussion.

Kansas trial court judges all have to face the voters to keep their positions, but only some face regular, contested elections. The others can be voted out, but a replacement is appointed. These retention elections tend to not have anything like the same level of campaigning.

It’s been shown before that regularly elected judges hand down more punitive punishments. Kyung Park shows that this excess burden of punishment is borne essentially entirely by African-American defendants, and that the patterns in this excess punishment seem to follow racism in the electorate (though that’s hard to measure).

The paper is here:

http://home.uchicago.edu/~kpark1/docs/Dissertation_Chapter2.pdf

So, just out of curiosity, are you saying that any authoritarian measure, such as appointing judges, leads to bad results, Graham? (This is without agreeing that such a measure is authoritarian.)

I guess I should also add a question about whether you think an election is always preferable to an appointment or hire (so consider it added).

Sigh. The original KKK was a lot of bad things, but before anything else, it was a violent resistance movement to an oppressive occupation. All other agendas were secondary, at most, to killing or putting the fear of God into the Yankees and the ‘collaborators’. -That last is where it got stupid and ugly – the targets of opportunity tended to be poor…

One man’s terrorist is another’s guerilla freedom fighter, and both men can be right at the same time, is all. Only hearing the ‘terrorist’ part all the time like it’s the whole of the truth gets pretty trying…

@BU

The KKK was a violent resistance movement to exactly one kind of “oppression” – obstacles that prevented white people from killing black people under circumstances where they otherwise would.

“Both men can be right at the same time” is what one man says when he realizes that the other is winning.

It also happens to be true much of the time…

It’s never true.

Half the people can be part right all of the time, and some of the people can be all right part of the time, but all of the people can’t be all right all of the time. I think Abraham Lincoln said that.

@Noah

I didn’t link appointing judges to actual anti-democratic regimes and I didn’t say it was illegitimate, I said it was authoritarian.

What’s the point? Ultimately that I think the currently dominant faction of the American left (which is not exactly you – you’re too weird for that; which I hope it’s clear I mean as a compliment – but is you more than me) wants institutions and policies that are modestly but significantly more authoritarian than what the most of the masses want (the same currently goes for the second and third biggest industrialized liberal countries, France and England) (it’s indicative that Democrats have won every presidential election in Vermont and Maine as of 1992 – that is, New England, which has always been a more authoritarian place than America as a whole, and the only states where FDR lost every single time, as did Truman and Kennedy (in the four more urbanized New England states, the regional disadvantage was outbalanced by the Democrats’ advantage in urban areas everywhere)) – which I find personally unappealing, elitist, and politically self-handicapping.

@Petar

I’m not saying any authoritarian measure is bad. I don’t think an election is always preferable to an appointment or hire. I’m not saying appointing judges is bad at all times in all places. I am saying it’s bad in America today, where the judiciary has become a means for enacting policies that the elite likes when they can’t get enough elected representatives to vote for them.

Thanks Scott. I believe John Pfaff’s research has suggested that a huge part of the problem with our criminal justice system is that elected DA’s are incetivized to try to get as long prison terms as possible. It’s a massive problem, and difficult to know how to address.

I think that’s an example of an instance in which more electiosn results in more authoritarian outcomes (i.e., expansion of the prison state, which is how the US does authoritarianism.) That’s why I don’t think using “authoritarian” as you are is helpful Graham…though I understand now that it’s a rhetorical rather than moral word in your usage here. But I think pretending the word lacks moral connotations just ends up comfusing the conversation.

“wants institutions and policies that are modestly but significantly more authoritarian than what the most of the masses want”

I’m really not sure this is true. I don’t think most people have a very strong position on government structure issues. But fwiw, the prison state is quite popular, as are federal measures like soaking the rich. (I support the second, but not the first — so I’m half a populist I guess.)

It’s primarily a descriptive word – though I admit that I appreciate the effect of calling a spade a spade to leftists who, evading their ambivalence about authority, spend their lives carefully calling it something else.

Most people don’t have strong positions on anything, but they have learned reflexes. These are also known as “culture.”

The prison state is indeed popular. On the other hand, the wage suppression, and the destruction of the universal social programs we have and the obstruction to creating more of them – that create the poverty that makes our prison state possible, are very unpopular. So as usual the answer is: No, the masses aren’t right about everything – but compared to who?

I also think your statement that authoritarian measures are all bad right now in America is a bit myopic. If you agree that they would work well some other time (as you just did), then there is some system where they function as a useful and positive part. That means there is some other systemic issue which is poisoning their implementation, and that authoritarian measures themselves are not necessarily to blame for the abuses of the rich.

More importantly, if Scott’s student’s research is indicative of a much larger problem (which it seems to be, if John Oliver’s brilliant news/research summaries are to be believed (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=poL7l-Uk3I8)), that means that elections are also a really bad idea RIGHT NOW, because they lead to horrible abuses. This is without mentioning the influence of PACs in judicial elections, perverting a populist reform measure into yet another tool for the rich to abuse the poor through the judiciary.

So if authoritarian measures enable the rich to abuse the poor, and elections enable the rich to abuse the poor, then blaming authoritarian measures or elections in particular for the abuses of the rich in any part would be naive, because there is obviously some much larger systemic problem at play.

That was @Graham, my bad for being vague

I didn’t say authoritarian measures are all bad right now in America. Some authoritarian measures are always good everywhere. I said appointing judges is bad right now in America

“This is without mentioning the influence of PACs in judicial elections” – Well, now you’re half way to the historical fascist and communist contention that democracy is never actually democracy because the rich buy the vote.

@Graham

That’s a deflection, not an answer to the point. And I am nowhere near that contention, because I’ve made no such statement about democracy. We are debating the efficacy of elections as a tool for ensuring judicial accountability, not whether democracy is valid or not.

And you contend that appointing judges is bad right now in America. All the evidence cited here indicates that electing judges is bad right now in America (because it leads to demonstrable and known abuses that are quite disturbing). So Graham, where should we get our judges?

I said appointing judges was bad because it’s become a way for the elite to circumvent democracy. That’s not why you said elections are bad.

If we’re talking in the abstract and you think it’s better to have a dictator who hands down racially unbiased prison sentences to a democratic society that hands down racist ones, okay, but say so. I prefer the democracy, especially because as the world news keeps teaching us, socially liberal dictators don’t make sexual and ethnic prejudices go away, they just repress it until they lose power, at which point they come back with a literal vengeance.

If we’re talking practically, I would say electing all judges in America would produce a less oppressive situation for everybody, including black people, than the one we have now. You mentioned Super PACs – well, who gave us (the highly unpopular) Citizens United ruling?

” I would say electing all judges in America would produce a less oppressive situation for everybody,”

I really doubt that’s true. It seems like a statement of faith rather than an empirical truth. You’re trying to have it both ways; you’re saying democracy is a moral good in itself, then insisting it will lead to the outcomes you prefer.

Again, electoral incentives for prosecutors seem to be a major factor pushing our crazed carceral system.

Popular opinion is pretty ambivalent about most welfare state measures, isn’t it?

I think looking to more direct democracy to solve problems is mostly wishful thinking, though disenfranchising people is bad in itself.

@Graham

“I said appointing judges was bad because it’s become a way for the elite to circumvent democracy. That’s not why you said elections are bad.”

Well, now I just don’t know what you’re saying. “Circumventing democracy” is an incredibly broad term which really means nothing. What concrete problems are caused by appointing judges? And no, “circumventing democracy” while it sounds terrible (and is) is not a concrete problem.

“If we’re talking in the abstract and you think it’s better to have a dictator who hands down racially unbiased prison sentences to a democratic society that hands down racist ones, okay, but say so.”

That is an absurd false equivalence. Appointed judges are not totalitarian dictators, they’re civil servants with relatively limited, if profound, power over their jurisdictions. Calling them dictators is great rhetoric, but inaccurate in reality. They are merely one part of a complicated apparatus.

“If we’re talking practically, I would say electing all judges in America would produce a less oppressive situation for everybody, including black people, than the one we have now.” Except all evidence to date of the effects of elections on judicial behavior suggests the exact opposite. Judges from local to statewide levels respond to elections by handing down harsher sentences, extorting trial lawyers for donations, and ruling in favor of their corporate campaign donors an astounding amount of the time (all of this in the John Oliver vid). In other words, judicial elections create multiple enormous conflicts of interest that promote glaringly undesirable judicial behavior.

“well, who gave us (the highly unpopular) Citizens United ruling?” This is also a deflection, but oh well. The whole point of having appointed Supreme Court Justices is to insulate them from public opinion and allow them to make unpopular decisions. This is by no means a guarantee their decisions will be good ones. But it does mean they largely (hopefully) avoid major conflicts of interest, which would no doubt arise if they were elected, given the overwhelming precedence there is to show that judicial elections are rife with such conflicts, and make their decisions worse. That’s the calculation anyways.

To summarize, if you’re looking for a place to start to make American representative democracy more democratic, responsive, effective, and less authoritarian, my vote (so to speak) is to start with abolishing the Electoral College, and somehow tackling the problems of Gerrymandering and Citizens United, meaning either overturning it or passing an amendment (there are already healthy activist efforts to the latter’s effect going on now).

I’m not saying democracy is a moral good, but if I were, I still wouldn’t be trying to have it both ways, I’d just be pointing out that you lose both ways: that is, democracy happens to produce something closer to the outcome you say you want.

Popular opinion is ambivalent (at best) about means tested welfare programs, which should surprise no one. Social Security and Medicare – universal programs – have been consistently popular ever since they were established; when W. Bush tried to kill the former, he got his first political defeat since 9/11.

@Petar

“Circumventing democracy” means what I said in the post before that one: “We want this and we can’t get the votes for it. Okay, let’s take it to court.”

I gave you the concrete example of Citizens United and further down in your comment you respond by calling it a “deflection” and then saying “Okay, it was bad, but at least it wasn’t caused by a conflict of interest,” which is both a non-sequitur and hilariously untrue. (Oh yes, Roberts, Thomas, Scalia, et al. are just objectively interpreting the law to the best of their ability. Not that only the Republicans do it, of course: The fact that it accomplished something we want doesn’t make Roe vs. Wade any less of a shameless sophistry.)

I’m all for abolishing the Electoral College (an abomination in principle, though the fact that its decisions almost always coincide with the popular vote makes it a minor problem in practice) and redrawing all states’ congressional districts on the model of the California Citizens Redistricting Commission. But abolishing the Senate, or even just making representation in the Senate merely as disproportional as it currently is in the House, would be an even more significant accomplishment.

@Graham

That definition of “circumventing democracy” actually indicts elections more than appointment. It’s shown, by research and reporting, that elections actually make judges more prone, not less, to subjugating their best judgment to the interests of wealthy elites.

I don’t understand the conflict of interest inherent to the Supreme Court that created Citizens United. Scalia, Thomas, Alito, and Roberts being virulent ideologues whose thinking is stuck in the Victorian era is not a conflict of interest. It just means they’re crazy. As for how the Supreme Court was populated by ideologues and crazies in the first place, well, appointments to the Supreme Court are all made by a consortium of elected officials in a (partially) public process. So your answer to the problem of Supreme Court decisions you don’t like seems to be to take away Supreme Court appointments from demonstrably corrupt elected officials, and make Justices into (almost inevitably) demonstrably corrupt elected officials. I guess my problem here is that you seem to be ideologically wedded to the idea of elections without considering all the pragmatic complications that make elections a potentially dangerous addition to certain institutions.

To what are you referring?

– If in “conflict of interest” you don’t include ideology, then who cares if they’re ruling the way they do because they owe some lobbyist or because their ideological allies do?

– I think your problem is you’re for democracy in theory, but ideologically suspicious of the masses and comparatively trusting of the elite in practice.

Welfare programs tend to be very popular after they’ve passed. They can be quite controversial beforehand (as with the recent health care reform.)

I think it can depend on particular politics of the moment too. Among other things, there isn’t generally a vast discrepancy between elite and popular opinion; public often takes its cues from partisan figures.

Do you prefer a parliamentary system Graham? I’m not necessarily against that…though European parliaments actually seemed to handle the recent economic crisis in a *less* populist fashion than the US did (at least if stimulus is seen as populist and austerity as less so.)

@Noah

– Yeah, but they did pass.

– There is an absolute opposition between elite and public opinion – the elite is always economically to the right of the masses (and at least as of the 1970s always sexually to the left), whether you compare the two groups in their entirety, or the elite of and voters for any major political parter, including the left-of-center ones.

– No, I prefer our system, partly for exactly that reason.

@Graham

I was referring to the research Scott’s student pursued, as well as all the information John Oliver presented in his segment on the topic, which was pretty damning if you ask me.

And…that’s a strange definition of conflict of interest. By that definition, it’s literally impossible to avoid one in any circumstance whatsoever, so the whole idea becomes meaningless. Everybody has an ideology which influences their decisions. Ginsburg has an ideology. Breyer has an ideology. Hell, even Anthony “change-my-mind-like-the-weather” Kennedy has an ideology. I don’t think it’s descriptive or useful to defined that term that way. But if you say so…sure, I guess.

As for being “for democracy in theory,” I consider myself a humanist, mostly because there is no other word I can find that fits my ideology very well besides. What I mean is, I try to evaluate any system by it’s concrete effects on people. I try not to have any ideological allegiance to a system (although that’s practically impossible…so sue me) unless it produces positive effects on the people it influences. I am trepidatious about whether elections actually produce public accountability, or whether they actually grant a veneer of legitimacy of process to the elites who game those systems anyway. At any rate, think what you like. It’s a free country.

Wow, this is embarrassing. Wary is a much better word for that sentiment than trepidatious. My bad…

– Well, that’s not evidence of “subjugating their best judgments to the interests of wealthy elites,” that’s passing judgments that conform to the racism of the electorate (whatever their private “best judgment” might be).

– I’m not saying judges shouldn’t have ideologies. I thought you might be.

– The word “humanist” makes me think of Renaissance aristocrats.

– Positive effects according to whom?

– Eh, free-ish.

I like trepidatious – it sounds like a hippie superlative.

“the elite is always economically to the right of the masses (and at least as of the 1970s always sexually to the left), whether you compare the two groups in their entirety, or the elite of and voters for any major political parter, including the left-of-center ones.”

I’d have to see a fair bit of data to convince me it’s always true, though I’d suspect it’s often the case. The problem is that economic and criminal justice issues are really entwined in the US, and I don’t think public opinion is always to the left of elites there.

I think the US could pretty easily have chosen austerity too; Obama’s done a lot of things I don’t much like, but he deserves kudos for the stimulus.

The stimulus should have been bigger, the bankers should have been forced to accept more regulation before he saved their lives, and inflation should be higher, but yes, he deserves a considerable amount of credit for not letting us become the economic black hole that Europe now is.

Though this is more a story of German pathology – and to a lesser extent that of the other European elites for submitting to it, especially the French, who are strong enough that it would be relatively easy to rebel – than any particular American intelligence: Japan is being about as sensible as we are, and even Britain looks good compared to the Eurozone.

re incarceration, in America we send the poor to jail. Reduce poverty and you reduce the incarceration rate.

I think that’s confused, Graham. The two are interrelated. Part of why we can’t reduce poverty is because of jail; i.e., reduce incarceration, you reduce poverty.

That’s one case where there really is a lack of democracy I’d say. Lots of incarcerated people can’t vote.

“The stimulus should have been bigger, the bankers should have been forced to accept more regulation before he saved their lives, and inflation should be higher, ”

I agree with all of that though.

@Graham

“Positive effects according to whom?” Ah, well determining what a positive effect is is kind of a fuzzy science. The general measure is the utilitarian approach, which is that you want the greatest amount of happiness to be experienced by the greatest number of people. That’s not very precise, but it’s a good start. As for a good middle, this serves well enough:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FqZ2evtU0Yg

Aristotle had a theory about what best secures the greatest good for the greatest number of people. It involved enslaving a minority for the benefit of the rest.

@Noah

We’re talking about the elite versus the masses. The point is if the masses have their way then there are harsher jail sentences but fewer poor people to receive them.

If you’re saying felony disenfranchisement should be abolished, I agree.

Okay; so we’re completely off topic here. It’s been civil and fun, but maybe we should wrap it up? I’d like to leave the thread open in case anyone wants to talk about Chris’ post, but the democratic theory discussion has maybe gone on long enough at this point…?

Can Clark Kent vote? I mean, in the versions where he’s brought to an orphanage, no problem, but what about the ones where the Kents find him and bring him home? Did they bribe somebody to sign the birth certificate?

Come to think of it, do superhero immigrants from outer space have to obtain visas?

@Graham

Aristotle was clearly full of shit. I’m done now.

He was much smarter than any of us. A humbling reminder of how many mistakes we’re all probably making. (I’m one to talk.)

The canon on Clark Kent’s citizenship is that he’s found in the spaceship, then there’s a massive winter storm, they don’t see anyone for a couple of months, and come out saying they had him themselves.

Thank you!

Which canon? On Earth One up to the mid-80s, he was about a year old when he came to earth, and Noah’s version.

The latest I know of, he was sort’ve born on Earth (the ship was a birthing matrix with a star drive stuck on; I didn’t write it) but they reboot every five minutes these days, so beats me if that’s still the case.

IIRC there was a recent story where Superman renounced his US citizenship? (Which would imply that Kent couldn’t also b a citizen, which I find implausible, so I might be misremembering the coverage of that story)

Wikipedia says Noah’s is John Byrne’s.

Though as far as I’m concerned the closest thing to a definitive Superman is the Fleischers’, so I reserve the right to make up my own story.

Or, you know, maybe it’s the ’90s animated series. That makes me uncomfortable, because obviously the Batman series is better, and Batman shouldn’t be better than Superman, but Dana Delany is the best Lois, who has of course always been the real hero, and to say that Clancy Brown is the best Lex Luthor would be an understatement, because he simply is Luthor, period.