This piece first ran at Slate.

_____

Even by the wretched standards of the entertainment industry, superhero comics are known for their dreadful labor practices. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the creators of Superman, famously sold the rights to the character to DC Comics for $130, and spent the latter part of their lives, and virtually all their money, fighting unsuccessfully to regain control of him. Similarly, Jack Kirby, the artist who co-created almost the entire roster of Marvel characters, was systematically stiffed by the company whose fortunes he made. Though most of the heroes in the Avengers film were Kirby creations, for example, his estate won’t receive a dime of the film’s $1 billion (and counting) in box office earnings.

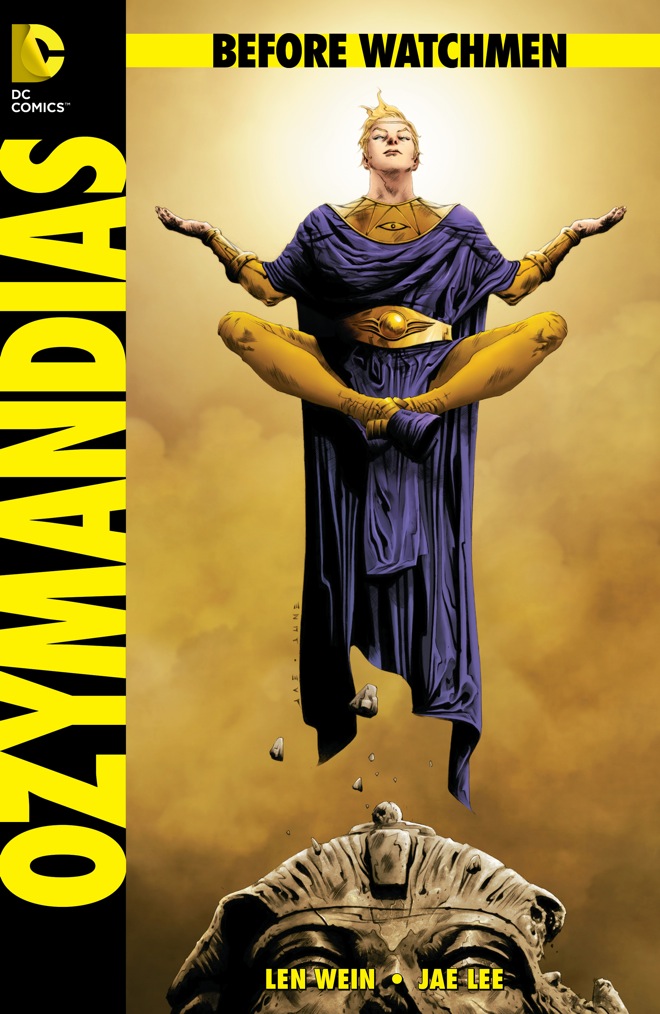

In keeping with this depressing tradition, DC will, next week, begin releasing new comics based on Watchmen, Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s seminal 1986-87 series. Before Watchmen will include not one, not two, but seven new limited series, written and drawn by some of DC’s most popular creators, including Brian Azzarello, Darwyn Cooke, Amanda Conner, and Joe Kubert. Watchmen demonstrated to a mainstream audience that comics could be art, and became one of the most popular and critically acclaimed comics of the last 25 years. Up to now, it had also been one of the most sacrosanct. For over two decades, DC has resisted the urge to publish new material featuring Rorschach, Dr. Manhattan, or the Comedian.

You’ll notice the list of writers and artists involved with Before Watchmen includes neither Moore nor Gibbons. This is not unusual in superhero comics. Most work for DC and Marvel is created on a work-for-hire basis. Thus, the original creator of, say, Walrus Man will usually go into a deal with one of the big two comics publishers knowing that the Titan of Tusk will become the company’s property—his aquatic adventures to be written and drawn by whomever the corporate overlords deem fit.

What is unusual, though, is the vehemence with which the original creator has denounced Before Watchmen. It’s true that back in the ’80s, DC tried to get Moore and Gibbons on board for a sequel. That didn’t pan out, though, and in the ensuing decades, Moore’s relationship with DC has soured, to put it mildly. Among (many) other things, Moore became increasingly angry with the company over the handling of the rights to Watchmen itself. In the original contract, DC had written a provision stating that the comic and the characters would revert to Moore and Gibbons once the series went out of print. Moore had assumed that, as with all comics in those pre-“graphic novel” days, this would happen within a few years. Instead, of course, Watchmen was a massive hit—so massive that the trade paperback collection of Watchmen has been in constant publication, and probably always will be.

Gibbons has largely seemed content with DC’s perpetual ownership of Watchmen. Moore, though, is a different story. He refused to accept recompense for the 2009 Watchmen film, which he referred to (sight unseen) as “more regurgitated worms.” As for Before Watchmen, he made his position painfully clear in an interview: “I don’t want money. What I want is for this not to happen.”

Watchmen‘s canonical status, combined with Moore’s dissent, has led to an unusually vocal backlash against DC. Chris Roberson, a sometime DC writer, decided to stop accepting work from the company because of its record on creator’s rights. Cartoonist Roger Langridge, who wrote the acclaimed series Thor: The Mighty Avenger for Marvel, followed suit, explaining that “Marvel and DC are turning out to be quite problematic from an ethical point of view to continue working with.” And Bergen Street Comics in Brooklyn will not be carrying the Before Watchmen titles; in explanation, Bergen Street’s manager, the comics critic Tucker Stone, said, “This is just gross, and we don’t want to be part of this one.”

It would be nice to say that Roberson, Langridge, and Stone are at the forefront of an all-out revolt against DC and Marvel’s business practices. That’s not really the case, though. For the most part, DC and Marvel’s writers and artists are still writing and arting as they always have; comics stores are still carrying the comics; and fans are still buying. Yes, if you go stumbling about in the comments of mainstream comics blogs (here for instance), you’ll find some outrage on Moore’s behalf. But you’ll also find a significant number of folks who don’t care, and who are actively irritated that anyone thinks that maybe they should care: As one fan said, “Alan Moore is a very arrogant guy that really hasn’t done anything relevant in a very long time and should really spend more time creating and less being a cranky old guy in a pub.”

J. Michael Straczynski, one of the writers on Before Watchmen, summed things up for many when he asked rhetorically, “Did Alan Moore get screwed on his contract? Of course. Lots of people get screwed, but we still have Spider-Man and lots of other heroes.”

Straczynski’s contrast between Alan Moore (screwed!) and Spider-Man (still ours!) nicely sums up the fandom dynamics of superhero comics. Creators are there to churn out marketable, exploitable properties … and then disappear. And because the comics companies own the characters, and because they have substantial marketing departments, they’re in a position to make that disappearance stick. Who knows who created all those different Avengers? Who knows who created Wonder Woman? Who cares? We want our modern myths packaged and available at our corner store and on our movie screens. Also … toasters.

Why is Moore complaining? It’s not about the money, as he’s said. (That’s probably a big part of the reason people call him a crank.) But Moore created a group of characters and the world they live in; those characters still mean something to him. Now a company he believes has screwed him over gets to colonize and even define that world. For example: Moore’s comics have often been concerned with feminism, and one theme of Watchmen is that the superhero genre is built in part on retrograde sexual politics and thuggish rape fantasies.

And how does Before Watchmen address these issues? Like so.

If this were some piece of fan fiction detritus—naked Dr. Manhattan, porn-faced Silk Spectre!—it would be funny. But given that this is an “official” product, it starts to be harder to laugh it off.

Of course, this is one of the things that always happens with art. If you create a beloved character or story, others are going to honor it, parody it, use it, and abuse it. That’s why there’s fan fiction. Indeed, Moore and artist Melinda Gebbie literally defiled Dorothy Gale, Alice (of Wonderland), and Wendy Darling in their exuberantly pornographic Lost Girls. Given that, what does Moore have to complain about exactly?

What he has to complain about is that he doesn’t own his own characters … and the company that does own them is free to pursue any version of the characters it likes, whether honoring Moore’s original vision (as DC has been careful to assert) or turning it into bland, infinitely reproducible genre product (as many suspect they will). And DC has the marketing might to ensure that, in the end, its version will be the one that’s remembered. After the third or fourth Before Watchmen movie, which iteration of the characters will be most familiar to the public? Rorschach and Nite Owl and Dr. Manhattan have been raised from their resting place, and Moore—and the rest of us—now get to watch them stagger around, dripping bits of themselves across the decades, until everyone has utterly forgotten that they ever had souls.

While I am totally (or almost so, anyway) on Moore’s, and your, side on this issue (no pun intended)–I did not buy and will never read the Watchmen prequels–is it perhaps worth addressing as part of this discussion that the Watchmen characters themselves are reworked versions of previously existing corporately-owned proterties, the original creators of which were not compensated (or even consulted, afaik) for Watchmen? I know we all know that anyway, but should it not be part of the discussion of Moore’s (legitimate) objections to how this situation has played out? I guess I’m just a little surprised that you mentioned some of Moore’s other character revamps (Lost Girls, about which I will refrain from commenting) but not being explicit about would seem to be the most germane one in this context: the Watchfolk themselves.

I think there’s a pretty big difference between taking inspiration from a character and doing “official” fan fiction against the express objections of the creators.

Fwiw, I’m fine with *non-official* fan fiction. Nite Owl/Rorschach slash; it’s out there somewhere, and more power to it. It’s the way that DC can market and promote this as being officially a continuation of the original that is gross (imo.)

The situation with Before Watchmen appears to have played itself out commercially. Last year’s Bookscan numbers show three editions of the original Watchmen book (at #87, 104, and 318) among the top 750 selling GNs. None of the Before Watchmen collections make the list.

As for the portrayal of the various author-publisher disputes, they’re far more based on fan lore than fact.

Moore’s characterization of the Watchmen contract’s reversion clause appear far more based on wishful thinking than the contract language. We don’t know for sure, because for all his ranting about the thing, he won’t release it for public scrutiny. But Gibbons has never seconded Moore’s portrayal of it, and Dick Giordano, who negotiated the contract, is on the record that DC’s reversion clauses are structured on a different model than Moore describes. Moore and Gibbons are also on the record that they always knew DC had the contractual right to do spin-off material.

The person who did the most to screw over Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster was not Jack Liebowitz and/or Harry Donenfeld, who were DC’s owners. It was Jerry Siegel.

The Kirby situation is murkier, but I’ll say this. Let’s say, before the Fantastic Four were created, Marvel owner Martin Goodman had offered Jack Kirby a choice of deals with character properties. He could have the equivalent of the J. K. Rowling deal with Harry Potter, which was a small advance against royalties. Or, he could produce material under the work-for hire circumstances that he actually did. I have no doubt he’d have picked work-for-hire. As far as he as concerned–and this is true of most work-for-hire comics creators–now money is worth more than later money, no matter how much the later money might be.

Well, in the case of Kirby — isn’t it telling that Marvel settled just after the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case? That argues that Marvel/Disney were pretty nervous about their legal position.

Mind you, the great majority of all civil suits end up in some sort of settlement, of course, so it’s best not to presume anything.

It tells me they settled. That’s all. It might have been just to avoid bad publicity. Or that Marvel had a standing offer that the Kirbys finally accepted. We just don’t know what the settlement is. However, we do know that Marvel retains the copyrights to their key publications, and that whatever was paid to the Kirbys wasn’t enough to be discernible in the shareholder reports.

As long as both parties are happy…fine.

“Why is Moore complaining? It’s not about the money, as he’s said. (That’s probably a big part of the reason people call him a crank.)”

Christ that’s depressing (because true).

“After the third or fourth Before Watchmen movie, which iteration of the characters will be most familiar to the public?”

In the short term – well obviously – but in the medium term, probably still Moore’s. That’s the nice thing about talent – it doesn’t necessarily make you money, but it’s harder to forget. (Everybody who knows anything about Wonder Woman beyond the name still knows she stands for benign matriarchy, and everybody who knows more than that knows she stands for bizarre kink. Batman in the collective subconscious is a combination of the ’60s tv series and ’90s animated series – by extension, to some degree, Steve Englehart’s – certainly more than Tim Burton’s, and maybe even more than Frank Miller’s (Nolan’s movies are of course fresh in everybody’s minds now, but clearly the only thing about those that has a chance of being remembered for long is Heath Ledger). Superman is a combination of Mort Weisinger’s and the first two Christopher Reeve films’ – for better or worse, that’s why his popular front roots are only vaguely remembered, if at all. And so on.)

I wish the teleology were that secure…but no one remembers the original Wonder Woman comics alas. I think popularity can swamp quality, given the right circumstances.

Before Watchmen seems to have done poorly enough that it is on its way to being forgotten, though, thank goodness.

I think most people remember more from the original Wonder Woman comics – even though most of them have never read them – than they do of any other particular version of the character.

And then, we know which version has proven interesting enough to scholars that… well, you know.

[post criticising DC/Marvel contracts]

[countdown to Robert appearing in comments to school us all on the non-viciousness of same: 3…2…1]

Hah; I was waiting for Robert to show up to. I did write this some time back, and I think Robert has convinced me that things were somewhat more nuanced than it put it here. I’d probably put it a bit differently if I wrote about it today.

I’m curious as to how other people feel about the decision to make prequels rather than sequels. [Or, rather, to make prequels first — sooner or later, the sequels will come too]. I feel like there’s an asymmetry in their effect on the original work, but maybe it’s just me.

You can easily imagine how editorial decided to do prequels: hey, a sequel would just look crass and feel like a cash grab. A prequel, though, now that’s classy — it’ll deepen our understanding of the original. But this seems backwards to me. It’s prequels that have the bigger effect on the original, because they retroactively change motivations and backstory in the original. A sequel you can brush off as What Happens Next, whereas a prequel actually changes What Happens in the Original.

Dunno if I’m articulating that well enough…to be honest, it’s kind of a moot point for most people who read Watchmen properly, because they couldn’t give a shit about DC and its shitty prequels/sequels/tie-ins/exploitation of the “property”, but it still bugs me

I think a sequel would’ve taken a lot more imagination on DC’s part. The flashbacks and Minutemen sequences in the original kind of laid the prequel ground for them (at least for some of those prequel books). Plus a sequel wouldn’t have fanboy favorite Rorshach, and it would be harder to place the other characters in the boilerplate superhero plots the before watchmen books appear to have laid out for them

I suspect “all the cool characters are dead” was probably the most relevant consideration.

Like that ever stopped DC (or Marvel)!

You’d really need to do violence to the story though. Not that they wouldn’t, but you can see why they might figure a prequel would be easier.

But that’s just my point, Noah — I think you do less violence to the story with a sequel than with a prequel. A sequel declares ‘this is what happens next’, while a prequel — or, at least the kind of prequel that these sounded like — says ‘this is what was actually happening in the bits you already read’. Like, from that take-down here, it sounded like the Comedian series changed some of the motivations in scenes from the real Watchmen. A sequel just adds extra scenes, but a prequel can also be more like recolouring or even redrawing scenes.

[Of course, none of this matters if you ignore the prequels, as you should. But the principle still stands]

Anyway, Dr Manhattan gives them an easy out for resurrecting Rorschach et al or retconning out events from Watchmen. The plot synopsis I heard (can’t find it online now) even made it sound like they were deliberately opening the door for this to happen further down the track.

If there is still a market for superhero comics in the future, we *will* see official Rorschach vs Batman sooner or later.

I think they did a prequel because Watchmen had an ending which was open to interpretation, like the short story “the lady or the tiger”. The effect on the original from a sequel would have been more blatant.

While the prequels also had effects, they really only come into play if you are the sort of comic reader that pays attention and does close readings. And if you were that sort of reader, you probably wouldn’t be reading DC comics anyway…

Also Moore and Gibbons did consider doing a prequel based on the Minutemen at one point. Apparently he said in 1988 “The only possible spin-off we’re thinking of is—maybe in four or five years time, ownership position permitting—we might do a Minutemen book. There would be no sequel.”

Actually, I think pallas makes a good point here. A good deal of the original work’s power came from its uncertain finale. If you did a sequel, it would have to resolve that uncertainty unless you did something surreal and somehow non-determinate, which I think is undoubtedly beyond DC/Marvel. Resolving the uncertainty there would have to either validate or invalidate Ozymandias’ final actions, and the whole point of the ending of that character’s arc was that he was in the dark about the results of his own plan despite his intelligence, influence, and previous self-assurance. Watchmen is the rare case where a sequel could do more damage to the original work, if any reader insisted on canonizing the sequel.

I may or may not have just redundantly reiterated what you said pallas. My bad…

I don’t think Watchmen had an open ending at all. Everything clearly signals that Adrians utopia are going belly-up. We even have a blue guy who can see the future say it.

Does Manhattan say it? I don’t have a copy of Watchmen handy, but doesn’t he say “nothing ever ends Adrian” or something very much like it? Thats not exactly definitive….

A sequel would make more sense, for reasons already given; a halfway decent writer could come up with something that didn’t detract (too much) from the original. Neil Gaiman managed to do it with his first Miracleman arc.

But with a Watchmen follow on, I imagine DC were after something closer to a regular superhero comic. Still, a more creative approach of the kind required by Watchmen wouldn’t get round the problem of screwing over Moore, or being a waste of effort that might be better put into something new, so theres not really much point in speculating.

Btw, is there any particular reason to assume Dick Giordano is/was a better guide to the original contract than Moore? Its mot like he was a disinterested party…

“not like he was a disinterested party” (obviously)

Giordano made it clear he wasn’t talking about the Watchmen contract specifically. He was talking about the reversion clauses in DC contracts in general. He wasn’t on the defensive about it , either. He was just asked about it, and it wasn’t in the context of addressing any grievance. It was in his interview in TCJ 119, conducted in late 1987. Moore wouldn’t start complaining about the Watchmen and V for Vendetta contracts for at least another 15 years.

I’m inclined to believe Giordano because the reversion structure he described would make far more sense for DC to use. According to Giordano, a property would become eligible for reversion if the property had been generating no income for a certain amount of time. The comics would not only have to be out of print, but there would be no money coming in from licensing–movie options, merchandising, and so forth. This makes more sense for DC because DC, then and now, is not primarily a publishing company. It’s primarily a licensing operation that does publishing on the side. If DC had to rely exclusively on publishing income, they’d have gone bankrupt in the 1970s. It’s been a rare year since then when the publishing side of the outfit wasn’t operating at a loss. I would think DC would want a contract that would not permit reversion unless there was no further licensing income from the property.

Moore’s statements at the time (click here)seem to confirm Giordano’s account. In 1986, while Watchmen was first being serialized, he said, “My understanding is that when Watchmen is finished and DC have not used the characters for a year, they’re ours.” The “have not used the characters” says to me there’s no income from the original comics and any outside project. The context of the statement, which is in a discussion that makes clear, among other things, that DC has the right to publish Rorschach-Batman team-ups, supports that interpretation.

Of course, Moore could clear all this up by releasing the contract for public scrutiny. There’s obviously no confidentiality clause in it. I would hope he isn’t doing what Steve Gerber did as a matter of course, which is lying to the press and fans about his publisher conflicts.

Personally, I think the reversion clause Giordano described is vastly more preferable to the author or authors, both from a practical standpoint and in terms of ethics. Out of print means the publisher no longer has copies for sale and isn’t expecting to print any more. That can be a lot harder to determine than whether the property is generating income or not. With the latter, the author or authors just have to keep track of when they received their last checks.

I also don’t think there’s anything unethical about DC keeping the publishing rights for as long as they’re able to sell copies. That’s standard practice throughout the publishing industry.

I read the prequels from the library…though it took me awhile to gird my loins to read the Rorschach/Comedian one. Pretty awful all around. Either they did absolutely nothing other than enact things only mentioned in Watchmen, or, as Jones says, they screwed with character development and motivation in ways that could taint the original if taken seriously. Only the Doc Manhattan one even had some interesting moments…but in general “cash grab” is the one of the kinder things one can say about it. G. Morrison’s Pax Americana from Multiversity is more interesting, since it’s kind of a meta- treatment of Watchmen (which was already meta-) with better art (than the prequels), new characters, a new story, etc. It’s still kind of superfluous, since everything it says/does, Watchmen says/does better (imo), but it’s pretty good and great by comparison to the prequels.

Thanks for taking the time to explain that, Robert. I was interested to find out what Giordano had to say, given his background as both freelancer and management, but a quick online search only turned up a couple of wiki references to old issues of the Comic Journal.

Still, while the info is appreciated, I don’t really see how later standard DC contracts are relevant here – you point out yourself that these were “vastly more preferable” to the Watchmen deal (don’t have a link – sorry – but I recall Gaiman suggesting that Moore would have been ok with something like the deal he had for Sandman).

Its clear that Moore believes he was misled – or later had his trust betrayed – by people at DC; whether thats reasonable or not I couldn’t say, but its hardly surprising that he had a different point of view when he was still actually working for them back in 1986, or that in itself that makes him wrong now.

The Watchmen contract was negotiated in 1985. Giordano’s account is from late 1987. I think that’s reasonably contemporaneous. The number of contracts that had been negotiated with reversion clauses at that point could probably be numbered on the fingers of one hand. I only know of three.

I don’t know where I’ve ever said that DC’s deals post-1985 were “vastly more preferable” than the Watchmen deal. The only significant improvement was in the early ’90s, when the Touchmark acquisitions set the precedent for author copyright and trademark ownership at the company. But keep in mind Moore would still be complaining about the reversion clause even if he and Gibbons did own the copyright and trademark.

I’d be very curious to read where Gaiman suggested that the Sandman deal would be more to Moore’s liking. From what I know of the agreements, the Sandman deal sounds inferior, at least technically. It’s a straightforward work-for-hire deal, without even a nominal possibility of reversion. The royalty percentages might be better, but to the best of my knowledge, Moore’s complaint isn’t about money.

When I brought up Moore’s statements in 1986, I wasn’t talking about his tone. I was referring to what those statements implied about the language of the contract.

I hope you realize that Alan Moore is complaining that DC did too good a job of marketing his material. They made his work so successful they didn’t have to give it back. He’s whining that his sales didn’t suck. It’s a Bizarro World complaint. I should feel aggrieved on an author’s behalf because his work has sold literally millions of copies, rather than selling poorly. Right. All authors should have it so bad.

I’m not standing up for DC across the board. I do think there is a strong possibility they misrepresented U. S. copyright law to Moore and Gibbons when negotiating the contract. I also think the Before Watchmen project was a sleazy venture. I’m glad it didn’t have commercial legs. But that’s it.

RSM-

I might be mistaken, but I don’t think Moore says that DC did something illegal, or even unethical within the framework of corporate capitalism. They said he could have the rights if DC stopped printing the book, and they never stopped. Nevertheless, they refrained from pissing him off further by not publishing sequels, making toys, etc. (maybe in the hopes that he’d do more work for them). I guess more did claim they ripped him off by not giving him money for a Watchmen button set, but that’s small potatoes.

Anyway, I believe what we have here is a classic case of conflicting values. You write:

“I hope you realize that Alan Moore is complaining that DC did too good a job of marketing his material. They made his work so successful they didn’t have to give it back. He’s whining that his sales didn’t suck. It’s a Bizarro World complaint. I should feel aggrieved on an author’s behalf because his work has sold literally millions of copies, rather than selling poorly. Right. All authors should have it so bad.”

This goes back to Noah’s point about people being unable to process why Moore can’t be satisfied with the paycheck and the let the issue drop. But I think we could also ask why we’re so quick to assume money makes things better, or why Moore shouldn’t want more (“want,” as opposed to expect is important here) from his former publisher.

Now, I know you’re going to say that Moore entered into the contract with eyes wide open, and I agree. And I don’t think he was tricked, and I don’t think he thinks he was tricked. After all, it’s not like he ever lawyered up and sued DC. But I do think he’s within the realm of reason when he expresses regret at his decision, and when he takes a dim view of those who put money before art, even if it’s their business to do so. In short, I don’t think it’s a Bizarro World complaint at all.

I don’t assume that money makes things better. I just think this is a silly grievance.

Moore’s language in describing the situation is far harsher than your comment suggests. He told the New York Times in 2006 (click here) that DC had “managed to successfully swindle me.” They’re not swindling him. They’re just insisting on maintaining a business relationship that he wants ended. They’re well within their rights to do so. And it’s fair that they do so as well. Taking into account page-rate advances, printing costs, and other expenses, DC probably invested over a hundred thousand dollars on each project before they saw a penny of return. They want a share of the harvest they helped bring into being, and I don’t blame them.

To Moore’s credit, he does understand to some extent what an entitled brat he sounds like. He also told the New York Times, “It is important to me that I should be able to do whatever I want […] I was kind of a selfish child, who always wanted things his way, and I’ve kind of taken that over into my relationship with the world.” Yup.

I don’t know Robert. You do in fact seem to be saying that Moore’s desire for artistic freedom, and his willingness to give up money to do it, makes him stupid, entitled, and perhaps unethical. It’s perhaps pie in the sky to want to be able to make art in a work for hire environment, but is it really immoral, or worthy of censure, for someone to be committed to their art? I don’t really see that.

While I agree that Moore comes across a good deal harsher, he is pretty clear in the interview that his grievance isn’t based on what’s ok from a legal standpoint, but what he sees as DC’s systematic failure to view his work in terms that aren’t monetary, and its willingness to leverage a brigade of contract lawyers to make sure they extract every cent of profit. Also, that article doesn’t even get the name of Moore’s artist on “League” correct, so I’m not too inclined to see it as a definitive account of Moore’s position.

Robert, “vastly more preferable” was your opinion of how the reversion of rights clauses worked for the author in the later DC contracts after Watchmen – second last paragraph in your comment after my first one.

The Gaiman thing was anecdotal, and I may have misremembered – possibly it was more his general treatment – or maybe not… I’ll try and track it down. But either way, it doesn’t change the basic point about the later contracts not being relevant.

As to the rest… is it worth getting into? There seems to be something of a catch 22 here – Moore refuses money so he’s an entitled brat, if he takes it then he can’t complain (Kirby style)

But do you really think the success of Watchmen was down to the marketing? Not saying DC weren’t efficient, but I’d say it was as much down to conditions in the mid 80s being conducive to a breakout work and Moore and Gibbons producing something that fit the bill. And bear in mind a part of that initial marketing was around the “creator friendliness” of the (then) “new DC” entering the direct market.

But I agree that Moore believes deception occurred around Watchmen.

www,seraphemera.org/seraphemera_books/AlanMoore_Page1

The difference is, I don’t think he comes across as particularly unreasonable; as far as I’m aware, for instance, he doesn’t go on about DC producing Hellblazer or new Tom Strong comics.

Noah–

I didn’t say he was stupid. I said he was being childish. He’s throwing a tantrum because he’s being held to agreements he made.

Sean–

You misconstrued what I wrote. I never said anything about contracts after Watchmen. I said that no-further-income reversion clauses were better than out-of-print reversion clauses. I don’t know that DC has ever used an out-of-print reversion clause in their contracts.

I said Moore was acting like an entitled brat because he was throwing a tantrum over not being able to get his way. I never said money was a consideration.

I don’t know why Watchmen was successful. By the same token, I don’t know why Moby-Dick and The Great Gatsby were flops when they were first published. Success and failure isn’t something that can be predicted in the arts. Efforts to explain it after the fact cannot help but be speculative.

He’s not throwing a tantrum. He’s voicing his complaints about the way his art is being treated. He doesn’t have any legal ability to stop it, and I don’t think he claims he does. But I don’t see anything immoral, or undignified, or childish, or stupid in saying that he thinks he and his work are being treated shoddily.

I sign contracts all the time that I don’t think are especially fair. As a freelancer, you have limited options. Agreeing to something doesn’t meant what you agreed to is just, and if you later point out that it’s not just, that doesn’t mean you’re a hypocrite.

First of all, I want to make sure we’re talking about the same thing. I am not talking about the Before Watchmen project. I am talking about Moore’s complaints about DC’s continued publication of Watchmen and V for Vendetta, specifically the reversion clause he and his collaborators cannot take advantage of.

His collaborators, specifically Dave Gibbons and David Lloyd, appear content with their relationship with DC. Unlike Moore, they have no complaints about

the reversion clause in the contracts. The disputes over the projects have created a situation where they are reportedly no longer on speaking terms with him.

As for Moore’s conduct, he has publicly called DC swindlers and thieves for simply exercising their right to continue to publish the work. He has also demanded that they remove his name from all projects of his that they continue to publish.

His collaborators have no problem with DC continuing to publish the work. They don’t appear to feel there was any chicanery on DC’s part during the contract negotiations. Moore didn’t claim there was any chicanery until twenty years after the contracts were signed.

Further, any publishing professional will tell you that, given the contract, DC would continue to publish the work as long as they felt it was worthwhile to do so. If DC wasn’t looking to do that, they would have offered a fixed-term agreement, where their rights would expire after a designated amount of time.

The credit removal demand is unprecedented. I cannot think of another instance in which an author has demanded his or her name be removed from a project after it has been published, particularly when there is no editorial dispute.

Now, if you don’t find Moore’s conduct over-the-top and unreasonable, i. e. a tantrum, I guess we have to agree to disagree.

Oh, okay; no I thought you were still talking about Before Watchmen.

That does sound a little over the top…though isn’t it connected to the film and the prequels? I know he hated the idea of them doing a film (with good reason as it turned out.)

Moore didn’t appear to have a problem with film adaptations until he saw how they were turning out. He agreed to license the film rights to From Hell and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, for instance. (As I recall, the League deal was signed before DC bought Wildstorm.) But the films ended up deviating from the books a good deal. Moore was also very unhappy with the League producers’ decision to settle a lawsuit, and that contributed to his antipathy. He doesn’t want to be identified with the film projects, in part because he doesn’t feel they’re representative of his work, and in part because he doesn’t like the business hassles that come with them.

As I recall, V for Vendetta and Watchmen were both optioned for film adaptations back in 1986. I don’t think the film rights for either ever reverted back to DC. Moore didn’t have any problem with it at the time.

However, I do think the film adaptations of V for Vendetta and Watchmen are what set Moore off with the complaints about the reversion clauses. The V film was made, and it was clear at that point Hollywood was going to move heaven and earth to get the Watchmen film produced. If Giordano’s account accurately describes the V and Watchmen reversion clauses, those films would render the clauses effectively meaningless. Even if the books never sold another copy, there would always be a revenue stream from the films. It might not be much, but even a box-office bomb generates continued income from video and TV sales. DC, Moore, and his collaborators would all but certainly get a percentage of that. Income from the property means no reversion. I believe Moore was savvy enough about the business at that point to understand what the movies being made would mean. I suspect what happened is that he lost that last little bit of hope that DC would eventually let go of the books, and he exploded.

Robert,

I can agree to disagree. I think Moore’s tantrums are understandable, and refreshing change from the “What are you gonna’ do,” arms in the air reaction of comics freelancers.

I do, however, think your characterization of Moore and his claims fails to account for the context in which it was released and for how the book was promoted by DC. With respect to the latter, and as Sean points out, DC didn’t hesitate to pat itself on the back for the creator friendliness of the deal. With respect to the former, were there any comic book mini-series that stayed in print, and if so were they anything more than the exception that proved the rule?

“DC didn’t hesitate to pat itself on the back for the creator friendliness of the deal.”

Please tell me when and where they have done this. I want to see exactly what was said, and by whom.

And Nate, just so you know, this isn’t the first time someone has confronted me with that claim. They weren’t able to back it up when challenged. As near as I can tell, it’s just a bogus piece of fan lore. I’ll be happy to be proved wrong, though.

I’ll look… If it’s bogus fan lore I’ll happily concede the point. What about the other point (about historical context)?

If you’re asking about other material that had been kept in print, gee, where do I start.

There have been book collections of Pogo, Peanuts, and Mad since the 1950s. There were book collections of ’60s Marvel material in the ’60s and ’70s. There were Batman, Superman, Wonder Woman, Captain Marvel, and romance-comics collections in the 1970s.

In the first of the ’80s, there’s quite a bit. Starblaze/Donning, beginning in the early 1980s, published trade-paperback collections of Elfquest that were distributed to bookstores. Dave Sim was publishing the Swords of Cerebus trade-paperback collections around the same time. Fantagraphics started the Love & Rockets book collection series in 1985, around the time the Watchmen contract was being negotiated. Moore was certainly aware of that one, as he provided a lengthy back-cover blurb for the first volume. Marvel published a trade paperback collection of the Elric: The Dreaming City serial from Epic Illustrated in 1982. They did their first trade-paperback collections from the standard comics line in 1984, with X-Men: The Dark Phoenix Saga and Iron Man: Demon in a Bottle. If anything, DC seemed behind the curve on this front.

And of course, there were multiple deluxe-format comic-book reprints during that time, too. From DC: the Neal Adams Deadman, the O’Neil/Adams Green Lantern/Green Arrow, the Goodwin/Simonson Manhunter, Kirby’s New Gods.

Moore seemed pretty supportive of DC’s trade-paperback program when it got going in 1986. This was despite his falling-out with them over the labeling issue. He wrote the introduction for The Dark Knight Returns collection. He also wrote an extended introduction for the first Swamp Thing book, and I think he even traveled to New York to help promote the collected edition of Watchmen when it first came out.

A quick search on Proquest turned up this quote from Jenette Kahn in Forbes (April 30, 1989):

“”When I first came in there were no creator’s rights, no licensing, no participation in reprint rights,” remarks Jenette Kahn. ”Now there are. We put the artists’ names on the cover, because we think they deserve credit. For 35 years, the artists labored in anonymity. It was a medieval industry.”

To be fair to Kahn, and to Robert, she’s referring not only to Watchmen but to DC in general. I think that Kahn is, rightly, associated with improvements to creator relations. Maybe I conflated the two, or maybe I’ll turn something up next time I’m thumbing through old comics or magazines. Regardless, I’ll refrain from reiterating the claim until I have something concrete.

I don’t know, Robert, the GN’s the book collections of comic strips strike me as an altogether different beast, as do the independent graphic novels, several of which have gone in and out of print multiple times over the years. The superhero collections you cited seem pretty few and far between, and I doubt they were in print when Moore signed his contract for Watchmen.

As for the Dark Knight intro, that was more or less contemporaneous with Watchmen, wasn’t it? Also, I recall Moore’s intro as an endorsement of Miller et al’s work and not an endorsement of DC’s graphic novel initiative.

I do want to say that while I don’t agree with many of your assessments, I do appreciate you taking the time to answer. Thanks!

The point is that book collections of material were not an alien concept to publishers or the creative people at the time or, really, at any time. It’s always been done if a potential market for the books is believed to be out there.

You can say things are different beasts. However, this is material that can be published as a book. I don’t think it’s a big leap of imagination to see that.

The point with the Moore-penned introductions is that if he thought the book program was an affront, potential or otherwise, to his rights, he wouldn’t have participated with it at all.

Oh, an amusing irony about that Kahn quote. While DC began including the creative teams’ names on the covers in 1984, the Watchmen serialization was an exception. Moore and Gibbons’ names aren’t on the covers of the original comics. I’m sure it’s not anything sinister; it was most likely a design choice Moore and Gibbons were on board with. But it’s a curious bit of discord.

Robert, apologies for where I may have misconstrued what you wrote; but in my defence, its a little unclear how you get from your first comment – where you suggest Moore could release the contract for public scrutiny – to being able to say confidently that he’s just being held to agreements he made.

But before I get it wrong further, can I ask a question? I think I’d understand your position better if I had a sense of what you consider to be a legitimate course of action for a freelance writer or artist in dispute with a publisher. Generally, how should they seek redress for perceived unlawful and/or unethical behaviour by an employer?

As Nate A above, thanks.

I didn’t mean to suggest there was no precedent for the book version of Watchmen, but that there wasn’t a precedent for a perpetually in print book version, which is what happened with Watchmen. I actually wonder if any other North American GN has stayed in print as long (or longer) than Watchmen.

Sean–

It depends on the situation. I’ve had grievances that have been resolved amicably. I’ve only had one that’s gotten particularly acrimonious.

With most disputes, you just politely approach the other party. You tell them you think there’s a problem. You don’t accuse them of anything sinister. You allow that it’s a mix-up or an oversight or whatnot. For the most part, things get resolved without any problem.

Sometimes you are dealing with unethical people. I once had to threaten a lawsuit against a publishing client to get paid the money I was owed. However, that’s something you only do as an absolute last resort, and only if you are absolutely certain you are legally in the right.

Sometimes you just have to walk away and put things behind you.

If you want me to point to a comics creator whom I think has consistently handled publisher grievances appropriately, I would say Neil Gaiman.

Nate–

As a rule, books stay in print for as long as sales justify keeping them in print. The Great Gatsby was initially a flop, but Scribner’s hasn’t let it go out of print since they first published it in 1925. The Sun Also Rises has been in continuous print from Scribner’s since 1926. To the Lighthouse has been in continuous print from Harvest (now Harcourt) since 1927. And so on.

There’s nothing special about comics or graphic novels as far as publishing contracts are concerned. A reversion clause that allows a publisher to keep publishing a book indefinitely as long as they keep it in print or otherwise generate income from it is standard throughout the publishing industry. It has been that way for decades. A fixed-term deal is not the norm. That kind of deal is invariably negotiated, and generally only by authors with a good deal of commercial clout.

As for GNs that have been in continuous print longer than Watchmen, there are a few. The Watchmen GN came out in September 1987. X-Men: The Dark Phoenix Saga was published in April 1984. Dave Sim put out High Society in June of 1986. Maus, Vol. I came out in August of 1986. The Dark Knight Returns GN came out that October. The Ronin GN was published in June 1987, as was Church & State, Vol. 1. Wolverine, which collected the Claremont/Miller series, came out in July of 1987. Cerebus, which collected the pre-High Society Cerebus issues, came out that August.

Robert,

I familiar how book contracts work, and I’m aware that many books had been in print for a very long time by 1986. My question was with whether there was any precedent for a comic collection being in print for that long. If I understand what you’re saying, the only continuously in print comics at the time was the Dark Phoenix Saga and High Society, and the former had only been out for a couple of years. Sure, GN contracts would work like standard book contracts, but it’s clear that there wasn’t much precedent for one staying in print. As such it’s not hard to imagine Moore thinking the rights would revert.

I don’t think it’s hard to imagine Moore would convince himself of that. People, no matter how intelligent, are able to talk themselves into all kinds of things. That’s why a good idea to at least consult with an agent or media lawyer before signing a publishing contract. It’s a situation in which you need informed feedback. You don’t want to get blindsided down the road. A decent agent would have told him that if he wanted the rights to revert, he would need to get a fixed-term agreement. Otherwise, it’s a gamble. There’s no guarantee the rights will be eligible for reversion until they are.

On another note, I gather from things Moore and David Lloyd have said that Lloyd always had a more grounded view of the V contract. He tried to talk Moore down from a rosy view of it. Apparently, Moore wouldn’t listen to him.

I also don’t think Gibbons has ever seconded Moore’s views of the reversion situation. Not the rosy view Moore had of it in the mid-’80s, and not the demonizing view Moore began spouting a decade or so ago.

If either Lloyd or Gibbons had sided with Moore in his complaints, or even confirmed his claim to any degree that DC misled them about the reversion situation during the contract negotiations, I might view this somewhat differently. But they haven’t. I can’t see this as a valid grievance on any level.

I think my criteria for validity are simply different from yours, which I interpret as being consistent with the majority view on how democratic capitalism should work: Moore is a rational actor who enters into an agreement with an a corporate entity, he expects to benefit from the agreement in fair proportion to said entity, both parties gain from the agreement, and so long as the agreement is not broken by either party a grievence will not be legally or ethically valid. On one level with your view, I symapthize, especially since I’m not sure what an alternative framework could or should look like. On another hand, I don’t think it’s intellectually or ethically invalid to reassess the wisdom of the original decision, or the fairness of the terms. I also worry about accepting the fairness of these agreements given that most individual creators aren’t in much of a position to dictate the terms of their contracts, but that’s very much my beef and it’s out of step with the majority view.

Robert – Gibbons and Lloyd not necessarily being in agreement with Moore doesn’t tell us anything about the original contract.

I read that piece you wrote about the Gerber legal action, which was very clear. Seems like you’re trying to take the same approach commenting on Moore and Watchmen – forget the fan lore or whatever, here are the facts! – but in this case, you don’t have the facts. Theres no primary source (ie the original contract), so you’re left with supposition.

Anyway, I asked about your general take on how a freelancer should behave because what looks like a tantrum to you comes across to me as a reasonable course of action. Moore thinks he’s been ripped off by DC, so he stopped working for them and feels free to give his opinion when asked.

For whatever reason, you think he shouldn’t feel ripped off… but rightly or wrongly he does,so his actions seem fair enough for someone in that situation.

Re: Moore’s complaints about reversion rights. I agree with Robert that Moore seemed perfectly happy with the contract, the series, and the treatment at the time. A couple of things changed that. I would say…1) The “buttons” for which Moore received no royalties, as they were labored “promotional”–despite being sold for $. 2) The mature readers label and such. I think #1 was actually a bigger deal, since DC seemed to be making dough off Watchmen without Moore/Gibbons seeing any, AND there seemed to be lying/chicanery around said money. I think it was these two events that made Moore want to leave DC altogether…and because of that desire, he didn’t really want DC to continue to have ownership rights (and thus make money) from Watchmen. The later complaints about the films (V for Vendetta) made Moore want to leave ABC/DC the second time…and by the time of the Watchmen film, he hated DC/Warner with the white hot intensity of a thousand suns. Moore was interested in writing Watchmen prequels (esp. Minutemen) and was generally jolly about being treated so well by DC (as compared to his time at Warrior and 2000 AD). He says as much in interviews around that time (some of which can be found in my book collecting them). Things went sour fairly quickly, but I think the buttons and the labeling led to the dissatisfaction with the contract. He might have been somewhat surprised by the results of the reversion, I guess, but as Robert says, it didn’t really vary from other contracts at the time. I’m pretty sure he even said that it would be great if it stayed in print, since that meant people would be reading it. Obviously, he changed his tune after that.

labeled, not labored

Eric–

My recollection of the button situation was that it was resolved in fairly short order, and in Moore and Gibbons’ favor. It sounded like a hiccup. Those do happen.

If memory serves, the matter didn’t become public knowledge until after it was resolved. Moore went off on a tangent in an interview for a news report about his plans for Mad Love. It was in TCJ 121, I think. As I recall, the reporter was too lazy to contact either Gibbons or DC for comment. I’m not sure either one has commented on it to this day. If they have, I’d be interested to read what they have to say.

The ratings controversy was silly from top to bottom. I remember discussing it with Kim Thompson and a few other people on a TCJ comment thread at one point. Kim and I both agreed it was a bunch of nonsense.

I’ve noticed that when things go sour with Moore, they go sour fast. He has a long history of 180-ing on people.

I don’t disagree with any of that. Moore has a tendency to identify people as “with him or against him.” Even if DC resolved the button thing, I think Moore started to get the sense that this wasn’t some kind of chummy artistic commune like the Northampton Arts Lab back in the day. Rather, of course, it was a business, where everyone was willing to do anything for a buck…even if that meant lying, massaging the truth, or doing stuff behind Moore’s back. His disillusionment, as you say, tends to be very rapid. He went into Warrior with a similar kind of sunny optimism, before quickly coming to believe that Dez Skinn was screwing everybody. His excitement about working for 2000 AD also flagged quickly. Basically, all the same stuff that was done with/to Moore has been done with/to innumerable other creators. The difference is that he is unwilling to just shrug stuff off as “business as usual.” He’d rather walk away. Some see this as him being a crank…others as him being unusually principled. My tendency was to see it as more of the latter. After reading his paranoic rant about internet persecutors and Grant Morrison (in his “final interview”), I’d start to move the balance toward 50/50.

All that said, Before Watchmen was an atrocity, both from an ethical and from an aesthetic point-of-view.

DC was contemplating doing Watchmen prequals without Moore’s involvement in the 80s, and it got back to him, which could also have been a factor in his disillusionment:

http://www.bleedingcool.com/2012/05/04/before-watchmen-nineteen-eighties-style/

There are conflicting accounts about whether DC intended to do spin-offs back then. Barbara Kesel says these proposals were taken seriously; Mike Gold says it never was, and wouldn’t be for as long as Jenette Kahn (and later Paul Levitz) were running DC.

Rich Johnston tries to give credence to Kesel’s account by hauling in an unnamed source at DC, but I don’t buy it coming from him. He has a history of publishing bogus reporting, and refusing to make corrections after it’s been pointed out. He prints what he wants to see out there, the truth be damned. The site is a rag even by the benighted standards of the comics press.

Moore gave a lengthy interview to Gary Groth in TCJ 138 in which he discussed his reasons for leaving DC. The ratings and button situations were mentioned. The closest he came to saying anything about spin-offs was this:

We were talking about the future of the Watchmen characters. We had been assured that we would be the only people writing them, that they wouldn’t be handed to other creators just to make a fast buck out of a spin-off series. There was a point where a highly placed person at DC did make a not terribly subtle – I think it was intended to be subtle but it wasn’t – insinuation that they would not give our characters to other writers to exploit as long as we had a working relationship with DC. It’s perhaps just me, Gary, but that was a threat and I really, really, really don’t respond well to being threatened. […] That was the emotional breaking point. At that point there was no longer any possibility of me working for DC in any way, shape, or form.

Moore doesn’t say anything about prequel projects being brought to his attention and yelling at Jenette Kahn to ixnay them. He just says “a highly placed person at DC” made an “insinuation” that spin-off projects were a possibility if he ended his working relationship with the company. That’s it.

If the most that happened was that Alan Moore perceived an “insinuation,” I’m inclined to given Jenette Kahn, Paul Levitz, and Dick Giordano the benefit of the doubt that this was never a possibility while they were running DC. Moore has a long history of paranoia. He wasn’t nearly as wacky back then as he is now, but as the ratings silliness demonstrated, he could get pretty loopy at times.

Finally, Moore makes no mention whatsoever in that interview of the reversion clause and Watchmen remaining in print being a problem for him.

“There are conflicting accounts about whether DC intended to do spin-offs back then. ”

My point wasn’t whether DC at the time seriously considered doing spinoff projects (I don’t care.) but only that Moore was concerned about it.

Moore’s contract was with DC Comics, not Jenette Kahn, Paul Levitz, and Dick Giordano.

Call Moore paranoid about other things, but he wasn’t unreasonably paranoid about the possibility of DC doing Watchmen spinoffs. He’s was right on the mark.