A lot has been written about Matt Fraction et alia’s run on Hawkeye. For example, see here for a HU discussion of the early issues, and here for a discussion of its depiction of disability in comics. I want to focus on issue #19, which is often discussed for its depiction of disability. The depiction of disability (or lack thereof) is an extremely important issue in comics studies, and I highly recommend Jose Alaniz’s excellent Death, Disability, and the Superhero (2014) for the reader interested in this topic. But I want to use issue #19 to examine a different issue – one that won’t surprise those of you who have read my other posts on this site. What I want to suggest is that Hawkeye #19 challenges our conception of what a comic book is.

A lot has been written about Matt Fraction et alia’s run on Hawkeye. For example, see here for a HU discussion of the early issues, and here for a discussion of its depiction of disability in comics. I want to focus on issue #19, which is often discussed for its depiction of disability. The depiction of disability (or lack thereof) is an extremely important issue in comics studies, and I highly recommend Jose Alaniz’s excellent Death, Disability, and the Superhero (2014) for the reader interested in this topic. But I want to use issue #19 to examine a different issue – one that won’t surprise those of you who have read my other posts on this site. What I want to suggest is that Hawkeye #19 challenges our conception of what a comic book is.

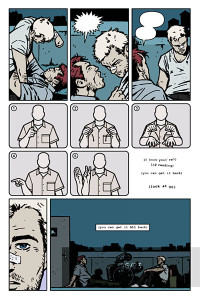

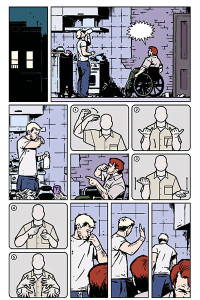

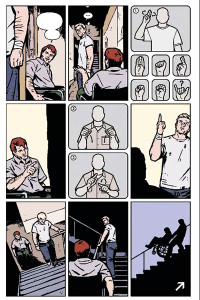

Hawkeye #19 is notable in that much of the communication in the comic occurs via pictorial representation of American Sign Language (ASL) rather than traditional speech balloons. Clint Barton is (once again) deaf due to an injury that occurred in the previous issue, and this is powerfully linked to his hearing impairment as a child – hearing impairment due to his father’s physical abuse. As a result, most of the communication in the comic (even in flashback scenes) is carried on via ASL, and language spoken by characters other than Clint is often depicted as empty speech balloons, with the shape or texture of the balloon itself roughly indicating emotion or emphasis, thus depicting this verbal communication (or lack thereof) from Clint’s perspective.

Now, in the academic and critical literature on comics, we are often told that one of the distinguishing features of comics is its unique combination of text and image. Of course, we know that there exist comics without any text – so called silent or mute comics. Marvel even had a special one-month ‘Nuff Said event in 2002 where many of their top titles published issues that contained no text. Nevertheless, textual information (in the form of dialogue, narration, SFX) is clearly a standard feature of comics. Furthermore, the special way that images and text interact, when both are present, is clearly an important feature of comics, since these two communicative modes interact differently in comics than they do elsewhere. Thus, explaining the way text and images interact within comics is (rightly, I think) taken to be one of the important outstanding problems in the academic study of comics.

Now, in the academic and critical literature on comics, we are often told that one of the distinguishing features of comics is its unique combination of text and image. Of course, we know that there exist comics without any text – so called silent or mute comics. Marvel even had a special one-month ‘Nuff Said event in 2002 where many of their top titles published issues that contained no text. Nevertheless, textual information (in the form of dialogue, narration, SFX) is clearly a standard feature of comics. Furthermore, the special way that images and text interact, when both are present, is clearly an important feature of comics, since these two communicative modes interact differently in comics than they do elsewhere. Thus, explaining the way text and images interact within comics is (rightly, I think) taken to be one of the important outstanding problems in the academic study of comics.

Nevertheless, even if all of this is right, and understanding the image/text combination in comics is important for understanding traditional comics that limit themselves to images and text, Hawkeye #19 demonstrates that this way of understanding the nature of comics is artificially limited. Now, Hawkeye #19 does contain a bit of textual dialogue, but let’s ignore that – Fraction et alia were clearly attempting to make an interesting and challenging experimental comic within the confines of mainstream superhero media, but were not interested, we can assume, in satisfying some absolute “no dialogue whatsoever”, Dogme-style constraint. But we can easily imagine a very similar comic that only communicated via (1) representational pictorial images and (2) inset depictions of communication via ASL. The question then becomes: what would such a comic teach us about how stories are constructed in comics? Before attempting to answer this question, two observations are worth making.

First, the depictions of communication via ASL within the comic (and within our similar, imagined entirely text-free comic) are not presented as straightforward depictions of the characters as they appear to each other when actually communicating in this manner within the narrative. Sometimes these scenes are depicted in this manner, but in many other cases the ASL is presented within inset panels that much more resemble pictorial instructions regarding how to sign than they resemble depictions of superheroes and other characters actually signing. In other words, these depictions of ASL are as much, or even more so, conventionalized and stylized depictions of the relevant communicative mode as are speech balloons within less experimental comics.

First, the depictions of communication via ASL within the comic (and within our similar, imagined entirely text-free comic) are not presented as straightforward depictions of the characters as they appear to each other when actually communicating in this manner within the narrative. Sometimes these scenes are depicted in this manner, but in many other cases the ASL is presented within inset panels that much more resemble pictorial instructions regarding how to sign than they resemble depictions of superheroes and other characters actually signing. In other words, these depictions of ASL are as much, or even more so, conventionalized and stylized depictions of the relevant communicative mode as are speech balloons within less experimental comics.

Second, these depictions of ASL are not text. Both text and ASL are conventional, primarily word-based modes of communication. But static images of a character signing are not, nor do they contain, the relevant ASL signs in the sense that an image of words contain those very words. The reason is simple: signing is dynamic and temporal, and text is static and atemporal. Further, text is compositional, while images are not. Hence static atemporal images of ASL signs are neither ASL signs themselves nor are they some sort of text encoding ASL signs.

Now, what does all of this suggest about traditional ideas regarding the centrality of image and text, and the interaction between the two, in comics? Well, the most obvious thing to point to is that the traditional text+image account of the nature of comics is far too narrow, since it won’t address the equally interesting and fruitful role that (pictorial depictions of) ASL can play in a comic, as evidenced by Hawkeye #19. More generally, what it suggests to me is that comics are not characterized by the interaction between image and text, but rather by the interaction of any number of static (unless we want to complicate things by bringing motion comics and the like into the discussion) visual modes of communication, whether these be representational images, text, conventionalized and stylized instruction-book like images of American ASL, or any of a host of other visual modes of communication.

Now, what does all of this suggest about traditional ideas regarding the centrality of image and text, and the interaction between the two, in comics? Well, the most obvious thing to point to is that the traditional text+image account of the nature of comics is far too narrow, since it won’t address the equally interesting and fruitful role that (pictorial depictions of) ASL can play in a comic, as evidenced by Hawkeye #19. More generally, what it suggests to me is that comics are not characterized by the interaction between image and text, but rather by the interaction of any number of static (unless we want to complicate things by bringing motion comics and the like into the discussion) visual modes of communication, whether these be representational images, text, conventionalized and stylized instruction-book like images of American ASL, or any of a host of other visual modes of communication.

Of course, this should have already been obvious, if one pays close enough attention to comics. After all, there is another static visual mode of communication, distinct from both text and image, that occurs frequently in comics: musical notation. Note that musical notation is usually used in comics, not as an actual notation to indicate a particular work of music, but instead as an indication of the presence of music without indicating which work or sometimes even which style (counter-instances in Schulz’s Peanuts notwithstanding). And of course Mort Walker long ago published his compendium of similarly-functioning emanata titled The Lexicon of Comicana (2000). So the idea that comics involve other modes of visual communication beyond representational images and text (in narration, dialogue, or SFX form) is far from new.

Nevertheless, Fraction et alia do give us something new in Hawkeye #19: an experimental comic that demonstrates the wide range of visual communication strategies open to comics creators by utilizing a novel such strategy: visual depictions of ASL. Thus, although the theoretical point is not new, this comic does represent a new way of making it, and a new way of making comics.

I’ll conclude in the time-honored PencilPanelPage fashion, with a question. If Hawkeye #19 shows that pictorial depiction of ASL can be used as one of the multitude of visual depictive modes in comics storytelling, then does that mean that visual depictions of ASL are always comics? Note first that a similar inference doesn’t go through for text (on any but the most generous accounts of what, exactly makes something a comic): text is a much more familiar mode of visual communication in comics, but not all strings of text are comics (even if it seems to be at least theoretically possible to construct a comic that does consist solely of text – see my own “Do Comics Require Pictures? Or Why Batman #663 is a Comic” in the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism). But a work that consisted solely of visual depictions of characters communicating with one another via ASL would, at the very least, look much more like a comic than a typical prose-only novel or short story would. So, if we were to take a short novel – Paul Auster’s City of Glass, say – and translate it into ASL, and then make an individual drawing of an anoymous narrator signing each word in turn, and then print the results – say, six such images per page, in the proper order – is the result a comic?

I always think the answer to these definitional questions is, “it depends.” Representations of ASL in a Hawkeye comic are definitely part of a comic. If the ASL signs were in an instruction manual, probably most people wouldn’t think of them as a comic.

It’s not just a formal question, in other words. It’s an issue of social contexts, which would include things like mode of distribution, expected audience, etc.

Fair enough. I agree that the issue is not completely formal (although I think it is at least partially formal: no pattern of production, distribution, and audience consumption can make my car a comic!)

But what if we consider multiple cases where we fix production, distribution, and consumption in different ways: Take the City of Glass example, and imagine two versions: one produced and distributed by Marvel comics, and sold in comic shops, and the other produced and distributed by the National Association of the Deaf, and sold at their events. Is the first clearly a comic? Is the latter clearly not? I am just not sure.

I don’t think either is “clearly” a comic, but yes, I think the one sold by Marvel is much more likely to be perceived of and treated as a comic.

How your car can be a comic:

https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2013/10/can-a-coke-bottle-be-an-indie-comic/

Roy, I would differentiate here between “a comic” that is participating in the artistic-literary tradition of comics (which is a definition of “genre” that emphasizes works as responses to other works) and “a comic” that is a work that uses the comics or the image-text method. A street sign (or several street signs) that combines abstract images (of, say, children walking) with words (such as “School”) is not a comic in the genre/tradition sense, but the signs do express meanings by combining words and pictures in a way that comics theory is best situated to analyze.

Personally, I think the ASL-translation of Auster would be a comic regardless.

As Noah says, “more likely to be perceived of and treated as a comic,” that’s a “comic” in the genre/tradition sense.

A “comic” that is not perceived and treated as a comic is an object that combines images (including possibly words) in a way different from or for different artistic purposes than works that are perceived and treated as comics.

And so the ASL-Auster is probably in the second category.

I think that the passage:

“More generally, what it suggests to me is that comics are not characterized by the interaction between image and text, but rather by the interaction of any number of static […] visual modes of communication”

Highlights one fairly under-appreciated aspect of comics.

I must ask, though: I am convinced that Walt Simonson once said that comics are “illustrations with a time arrow”.

I am half-tempted to say that the temporal dimension in comics is still static (several distinct moments co-exist in a page, etc.), but I was wondering what your intuitions would be, on this matter.

Thanks in advance,

F

Noah: Well, I know what you mean, but you got all wishy-washy in your phrasing: The original question wasn’t whether something will or won’t be perceived or treated as a comic (things get perceived or treated wrong all the time) but whether it is a comic. Of course, I suspect you think that there often isn’t any genuine fact of the matter about the former (at least, none over and above how we perceive things to be), but I disagree (even though I do think that such facts, objective though they are, are at least partially constituted in terms of patterns of production and consumption, rather than being grounded solely in formal characteristics of the work itself).

Chris: With regard to your first comment, and the distinction between “a comic that is participating in the artistic-literary tradition of comics” and “a comic comic that is a work that uses the comics or the image-text method” but presumably doesn’t fall into the first category, I would prefer just calling these “comic” versus “work that isn’t a comic, although it borrows techniques from the comics art form”.

With regard to your second comment, my intuitions run the other way. As long as the illustrations were generic and had no connection to the story being told other than the gestures indicated in the depiction of the ASL signs themselves, I feel pretty confident that it’s not a comic. But I have nothing insightful to say about why it isn’t (hence part of the reason for writing this post!) – it’s just a raw intuition.

Chris: Again, as in my comment to Noah. I just am not all that worried about what is or is not perceived as a comic – I am worried about what is, and is not a comic. Of course, this kind of response hides a deeper disagreement about what the nature of art forms, genres, etc., between Noah and yourself versus me, I suspect (and Noah and I have hashed out similar disagreements in the comments sections to past posts). I just don’t think what makes something a comic boils down to whether people take it to be one – I am instead open to at least the possibility of massive error: that everyone could think something is a comic, and treat it as a comic, yet it still not be a comic.

In short, although I think patterns of production and reception are part of the matrix of factors that contribute to determining whether something is an art work or not, and whether something is an artwork of a particular kind or not (e.g. comic), I also think that Noah and others like him vastly overestimate the contributions such social factors make, and underestimate the contribution of other factors (including formal ones). In short, I don’ think a Coke bottle could ever be an indie comic, regardless of how it was shown and how we reacted to it, and no matter how strongly we all (for whatever reason) believed it was one.

Francesco: One thing I would say about temporality it this: The images themselves are static (they are, after all, just patterns of ink on the page, and don’t change other than the slow deterioration that comes with time). The way that the images are arranged on the page imposes a temporal order on the (imaginary) events that are depicted in the images. So the time arrow that Simonson has in mind (if we are to interpret him charitably) is not an arrow ordering images in real time, but an arrow ordering (imaginary) events depicted by images within the (imaginary) time of the narrative.

Roy, I’m intrigued by your intuitions, as well as their underlying assumptions. If we asked if Pluto is a planet, the (current) answer is no. We could also argue that Pluto was never a planet, everyone just erroneously thought it was, but that seems to imply that definitions are constants/absolutes and not human constructions and therefore moving targets. Pluto didn’t change, but did the definition of “planet” did.

So every traditional “comic” “borrows techniques from the comics art form” whether it is labeled a “comic” or not. I’m not sure it’s possible to formulate a set of necessary and sufficient formal qualities that limits “comics” to the tradition of comic book publishing. Every attempt (mine included) I’ve seen ends up describing many non-“comics” too. Worse, attempting to do so is akin to fiddling with the definition of “planet” in order to make Pluto one while making sure Ceres is not. The behavior is tradition rather than form motivated. When a work borrows some critical mass of comics art techniques it becomes a comic. Defining that formal cut-off point is pretty damn hard. Defining that point while really trying to cordon off traditional comics is likely impossible.

So, Roy, there’s some Platonic comic somewhere—a pure transcendental form invented sometime in the last couple of hundred years when comics came into being?

I just don’t find that idea credible. Art forms are agreed upon, not formally handed down. What’s perceived as a comic is the only comic you’ve got. If a tree falls in the forest and everyone mistakes it for a comic, you’ve got yourself a comic.

Noah and Chris: like you, I lean much (much) more towards a deflationary/social construction account of the concept COMIC. But I can think of at least one way to make sense of the idea that some things we take to be comics aren’t really comics — we might take COMIC to pick out a natural psychological kind.

Suppose, for instance, that something like (my vague picture of) Neil Cohn’s view turns out to be true. Suppose that there are specific psychological processes associated with our reading of paradigm comics. So, when I read (say) Fantastic Four #1, or a Peanuts strip, there’s a specific set of cognitive processes that go on, perhaps a unique combination of visual processing, linguistic processing, and action-parsing. It might also be that specific corresponding parts of my brain (visual cortex, language centre, etc.) “light up” when I read these things, so there are distinctive neural structures involved.

Now further suppose that this doesn’t happen when I read a laundry list (to use one of your favourite examples), or watch a superhero movie (to use another of your favourite examples), or think about cats wearing bowties (to use — no, wait). Then we might be justified in saying “aha, that’s what comics are — things that call on these specific psychological mechanisms and processes”. And it then might turn out to be that certain things people sometimes take to be comics don’t trigger these mechanisms (single panel cartoons without text being the obvious candidate). In that case it wouldn’t seem obviously crazy to say “oh, it turns out we were mistaken, and those things weren’t comics this whole time” and/or “oh, this thing we thought wasn’t a comic actually is one”.

This view doesn’t get you Roy’s formalism per se, but I could further conceive that there might be specific formal features associated with these psychological responses. Indeed, if there were distinctive psychological processes deployed for all and only a set of things we call “comics”, that set probably is definable formally. So ultimately the view would be “comics are all and only the things that have formal properties ABC, which typically trigger psychological processes XYZ”.

Like I said, I lean much more to a deflationary account of COMICS, and I doubt whether the view I just sketched is Roy’s (it might be too psychologistic, and it certainly doesn’t leave much room for massive error in people’s categorization). But that view doesn’t seem obviously crazy.

(Incidentally, nothing that Roy has said so far, AFAIK, entails a “Platonic” theory of COMICS — there’s other theories of concepts/universals/properties. But the Platonic theory would be crazier than you think; it would turn out that the Platonic form of comics didn’t just come into existence in the last few hundred years. The Platonic form of comics has always existed)

Right, I know Platonic forms of comics are always around. I was making a joke (or trying to.)

The problem with the psychological process explanation is that (a) identifying brain activity like that can be difficult and subjective. (b) there isn’t any particular evidence that this is what is happening (right?)

Oh, sorry about the platosplaining then.

I don’t see an in principle reason why doing the psychology of comic-reading should be any harder than the psychology of vision, or language comprehension and production, and we know an awful lot about those. But this is moot, really, since I doubt the view I sketched is Roy’s, and it’s not mine either — my point was just, well, here’s one imaginary sequence in the future history and sociology of science that could underwrite some of what Roy was getting at. (Even there, though, I still can’t help describing it in deflationary/social-constructionist terms; I want to say that as a result of these psychological findings, we decide that COMICS picks out such-and-such a kind)

I am not particularly attracted to quite so psychologistic a theory as Jones suggests, but his sketch of such an account of comics does highlight some of the issues I am concerned about.

I certainly don’t hold a purely platonic, or purely formal, view of comics either. I do think formal features are partially constitutive of the concept comics, but only because of complicated historical stories (which I am not qualified to actually give) regarding how it is that we decided that certain formal properties are central to an artefact being a comic.

Compare the concept “nation”. Now, clearly this concept is at least partially the result of certain decisions we (as a culture, or species, or whatever) have implicitly made with regard to what is to count as a “nation”. Nations, obviously, don’t occur in nature, or as natural kinds. But as a result of the conventions we have adopted, implicitly and over time, with regard to how we are to use this concept, there are certain criteria that, as a matter of these conventions, that history, and whatever else, are necessary for an entity to be a nation. In short, if I suddenly hypnotize everyone into believing that a Coke can is a nation, then (given the fact regarding how we have used the concept “nation” up until that point) I have hoodwinked everyone, and fooled them into thinking that the Coke can is a nation. I haven’t made it the case that the Coke can is, in fact, a nation.

I think the concept comic works something like this.

The obvious question raised by your view, Roy, is whether, in fact, “we” have indeed “decided” “that certain formal properties are central to an artefact being a comic”. Dickish comment thread way of putting the point: who decided, and when? Was there a party? Was Scott McCloud invited and, if not, is Ziggy still a comic?

I’m being facetious, of course, but lurking nearby are non-dickish, non-facetious versions of the same concerns…broadly, I suppose, about how and when social conventions set the reference of “comic” (etc.), how we draw the boundaries of those conventions (who’s disagreeing about comics, and who’s just talking past each other), etc.

I don’t think straightforward comparisons of comics to nations works very well. It’s like saying, “well, we strictly define triangles in geometry, therefore…” There are definitions and conventions in international law about what a nation is. Specific cases may be somewhat arbitrary, but there are just much more definitive (albeit of course still arbitrary) rules. Art doesn’t work like that. That’s part of what makes it (the ambiguous, contested category) art.

“There are definitions and conventions in international law about what a nation is.”

Actually, there aren’t. You seem to be confusing nation and state.

Noah: I guess my point really comes down to this: You seem to be presenting a pretty sharp dichotomy between (1) a view where the status of an object as a comic (or not) depends solely on person- and society-independent facts (i.e. some version of the platonic view you sketched, in a broad sense of Platonic), and (ii) a view where the status of an object as a comic (or not) merely boils down to whether or not it is currently treated as a comic by the majority of people (or the majority of people who matter, however we might settle that).

My own view (which isn’t completely worked out, but I am working on it) is that the truth lies somewhere in the middle: There is an objective fact about whether an object is or is not a comic, but that fact is partly constituted by various actions performed, and beliefs held, by the relevant communities (and I’ll admit that I don’t know how to specify who counts as ‘relevant’ here either). But the way that this works is much more complicated than being merely a democratic, who-thinks-it-is-a-comic-right-now, process. Instead, it involves a complicated historical process by which the relevant community (or communities) implicitly adopted various conventions and rules regarding how we are going to use the concept Comic. Once these conventions are in place, however, there are facts of the matter regarding whether certain objects are comics – facts that depend on these conventions and rules, and are independent of our current opinions regarding the comic-status of the object.

Of course, this history could have been different. And, had it been different, different things might count as comics in virtue of our having settled on different conventions and rules. But admitting this doesn’t entail that what counts as a comic is just whatever we decide is a comic. Compare language: words have the meanings they do because of certain conventions and rules that we have implicitly (and sometimes, as in the case of mathematical and scientific vocabulary, explicitly) adopted over the course of the evolution of language. Now, the meaning of expressions can gradually change, as our behaviors and attitudes change, but that doesn’t mean that there isn’t a fact of the matter, at any point in time, regarding what a certain word means. And this fact is not reducible to facts about how people currently use the word. For example, if everyone in the world, right now, begins using the word “momentarily” to mean “in a moment” (rather than “for a moment”), that wouldn’t be enough to make that the actual meaning of “momentarily”. The implicitly accepted conventions and rules for, and prior usage of, “momentarily” would trump a momentary (couldn’t help it) lapse where we all used the word incorrectly. Of course, if we continued to use the word to mean “in a moment” long enough, this might be enough to alter the relevant conventions and rules. but, just as the implicit adoption of conventions and rules didn’t happen instantaneously (except in special cases in, e.g., math and science), but is instead a process that occurred over significant spans of time, altering these conventions and rules also requires significant amounts of time. Hence mere agreement in usage doesn’t automatically, at the very minute we all so agree, change the meaning of the word.

Along similar lines, mere agreement at a particular time that an object is a comic doesn’t override the history, conventions, and rules we have implicitly adopted over time to govern the concept Comic. As a result, if tomorrow everyone were brainwashed into suddenly thinking some Coke can was a comic, they would just be wrong (of course, if we all decided there were some good reason to treat Coke cans as comics, and uniformly categorized them as comics, and provided explanations of why they were comics, etc., for long enough, then we might succeed in altering the concept Comic so that the Coke cans would be comics).

[It is worth noting that I fall very strongly on the prescriptive side of various prescriptive/descriptive debates in linguistics, and am thus applying these commitments to the concept Comics. Part of the disagreement might stem from deeper disagreement about these issues.]

Oh, and in response to Jones: I totally agree. So do lots of philosophers and linguists, and there is a rich and growing literature (both philosophical and linguistic) on what conventions are, how they are settled, and how they work (i.e how they obtain their normative, rather than merely descriptive, status). A good place to start at the philosophical end is David Lewis’s excellent Convention: A Philosophical Study (Harvard UP: 1987).

“Hence mere agreement in usage doesn’t automatically, at the very minute we all so agree, change the meaning of the word.”

Actually, I think it might. Words have no meanings independent of their usages. Dictionaries don’t define; they describe. They’re snapshots of objects in motion.

It’s true that word usages tend to evolve slowly, but if a thought experiment posits that everyone can simultaneously apply a new meaning, then in the non-slow-evolution world of the thought experiment, hasn’t the word changed?

Roy, could you say a bit more about what else besides formal properties determine comichood? You generally strike me as a gungho formalist, but you’ve said a few times now that formal properties only partially determine comichood.

I can think of at least two other things you might have in mind – that an object needs to have the right kind of causal history to be either a work of art, or to have content. But I’m curious as to whether that’s what you have in mind

Yeah; I’m definitely a decriptivist. I think (?) you’re referring to history as separate from social agreement, but I don’t think that’s accurate. People in the past thought x was a comic; we follow their lead and agree x is a comic. It’s still social/cultural agreement, just over time.

The idea, I think, Noah, is that the history is sticky. Once the conventions are settled, they’re stable for a while, until theres enough change for the convention to have shifted (for some unavoidably vague value of ‘enough’.

Hence the analogy with language. ‘Water’ means water because of how people have used the word, thereby fixing its referent. And so it would be incorrect for me to point to a glass of milk and say ‘water’. But if enough people started doing that, themeaning would change and i might become right

Oh, sure. I agree with that. I just still think it’s about cultural and social constructs, rather than about anything innate to comics.

There are two ways one could think formal notions are central to what makes an object a comic. The first is what I think of as formalism (maybe we should call it pure formalism):

X is a comic if and only if X has formal features F1, F2,… Fn.

This would be Noah’s platonic conception, where the criteria for comic-hood are formal and do not change over time. I am NOT a formalist in this sense.

There is a looser kind of formalism, however, that I do accept. It goes something like this:

(i) X is a comic if and only if X satisfies the rules and conventions we have adopted for the use of the concept COMIC.

(ii) The rules and conventions we have adopted for the use of the concept COMIC entail that formal features F1, F2,… Fn are particularly important for determining whether an object is a comic.

[Note: Saying formal features are particularly salient or important doesn’t entail that they are the only features that are relevant, by the way.]

Now, on this sort of view, the fact that the formal features are central is contingent – we could have adopted different rules and conventions (if the history of our use of the concept COMIC had been different). But the fact of the matter is that the conventions and rules we have adopted make it the case that formal features are central components of the manifold of considerations relevant to determining whether a particular object is a comic.

Thus, we don’t just decide to call this object a comic, and that one not a comic, the way suggested by some of Noah’s claims above. Rather, we adopt rules and conventions regarding the kinds of objects to which we do, and do not, apply the concept COMIC (of course, part of what adopting rules and conventions amounts to is making particular judgements about particular objects, but that is not all that is involved). These rules and conventions could have been different (and they could have involved formal features far less than they actually do). But given the rules and conventions that we have adopted, a Coke can isn’t a comic even if we are all brainwashed into thinking it does, because we are all (brainwashed or not) beholden to the conventions and rules governing the concept COMIC that we have, in fact, adopted, and at least part of those rules and conventions involve the idea that comics have certain formal features that Coke cans don’t have.

The problem there is with the “we”. Who is this “we” who are adopting these conventions? There’s no rules committee, right? So what’s the authority? Many people refer to superhero movies as comics. Where is the official body to tell them they’re wrong?

Jason Mittell argues that genres are constituted not just by experts, but by the general public, including folks with little interest in the genre. Certain groups can certainly adopt definitions by which something is a comic, but those definitions may be locally important, but they’re not necessarily universal, or even the most accepted criteria.

If I understand Roy correctly, the “we” is everyone involved in the thing we call comics past to present. Over time, anything could become a comic, but at any moment in time we agree that some things are comics and others are not. Sure, there are liminal cases and contested objects, and that’s when we begin to notice that a form is conventional and not natural (or Platonic), but for the most part we just happily act as though we all share the same definition of comic (even if there’s a lot of variation among individuals).

Again, though, one quite common definition of comic in popular culture is “a movie with superheroes in it.” I’ve had multiple conversations with people where they literally refer to a superhero movie as a comic.

So if those people are included in the “we” (and why shouldn’t they be?) it’s hard to see what formal qualities of comics we (broadly) agree on.

@Noah,

The people you refer to are definitely part of the “we,” and I don’t think they’re misguided. U.S. comics have been identified with superheroes for a long time. As such, I’m not surprised that the form of comics is defined by something we’d usually consider content (costumed superheroes). And I don’t even think this is a mistake given that the presence of a costume is the primary, formal difference between what people call comic book movies and other movies with the same, basic formal characteristics.

As to whether these people you’ve been talking to are part of the “we,” then the answer is yes, of course they are. Moreover, if enough people decide this is a good enough determination, and enough people start using the term comics to describe these movies, then the the formal definition will expand. Basically, the presence of superheroes will be a necessary and sufficient condition to call something a comic.

All that having been said, I’ve yet to hear anyone describe a superhero movie as a comic, nor have I seen this description in print. But I’ll keep my ears and eyes open.

Nah, Roy, I understand that, counterfactually, we could have construed COMICS differently (would I be right in sensing a 2d semantics lurking in the background?) My question was about COMICS as construed in the actual world – do you think that, here , comichood is completely determined by formal properties, and if not, then what else contributes?

Jones: our current concept of comic isn’t totally formal – although it might depend on how broadly we construe ‘formal’ (I wrote a paper a number of years back defending the view that a publication without any images at all could be a comic in virtue of being a numbered installment in a mainstream comic series – Batman #663 was the real-life almost example I discussed). But I do think that our actual concept is heavily weighted to formal considerations (even if other considerations do play a role). My main evidence for this is that when we are explaining why some works are comics and others not (e.g. When dividing Gaiman’s work into the comics and the non-comics) the first criteria we typically refer to are formal ones (American God’s isn’t a comic cause it has no images and is formatted like a novel, while Sandman is cause it’s got panels and balloons). Of course, publisher, intended audience, etc. makes a contribution too, but I suspect it’s less.

“when we are explaining why some works are comics and others not”

Again, who’s the “we”? if you’re talking about comics academics, you’re probably right. Some superhero fans might well point to content though (i.e., superhero films are comics, Chris Ware books maybe not.)

By not defining the “we”, you get to have it both ways; you claim there’s a social consensus about using formal properties to define comics. And in some communities, in some cases, there is a social consensus, no doubt about that. But in others there isn’t, necessarily. Why is the we that cares about form more important than the we that doesn’t?

“Why is the we that cares about form more important than the we that doesn’t?”

Welcome to the downside of analytic philosophy, Noah

I think that the “we” in any of these cases is a the discourse community under examination. If fans of superhero movies generally call the films they watch comics, and they do this without eliciting further questions, then superhero movies are, for them, comics. That having been said, I’m not sure Roy’s “we” is any vaguer than Noah’s “we,” as I suspect both are coming at the question based on the people they talk with when they talk about comics

A more productive question might be one of how widely agreed upon the concept of comics actually is. Based on the various discourse communities I encounter on the regular (in real life and via the media), I’d venture that most people cite formal criteria and purpose to make the cut between comics and other media.

For example, in my visual communication courses I show students a set of illustrated safety instructions and ask them to name the genre. Invariably, they call them airplane instructions. Next, I ask them to explain how they knew this, at which point they start describing the form and content. Then I ask them why, given the form and content, they didn’t call it a comic. Their minds aren’t blown. They just point to purpose: Comics entertain, instructions instruct. Then I show them an old Civic Defense Initiative comic instructing kids to duck and cover. Their minds still aren’t blown, but they do get a sense for the various factors (form/content/purpose) at work in a definition, and the decision to foreground one factor and background the others is just that, a decision.

” I’d venture that most people cite formal criteria and purpose”

Purpose is content, though, right? I’d certainly agree that genre is defined often by form and content…but also by distribution and audience and other factors.

I wasn’t positing a particular “we”. I was saying there are various groups of wes, and definitions probably depend on which group you’re privileging.

I don’t think it’s always the case that purpose is the same as content. Rather, content tends to reflect purpose, (as well as intended audience, implied author, etc.). The obvious example of this would be when content is repurposed, as when old government comics become items for entertainment, or when movie posters or album covers become art pieces.

I understood what you meant by we, and I agree that definitions of genre depend, in part, on which group we privilege. Still, I think Roy has a point when he suggests that there’s often a dominant definition that dominates, in part, because we associate formal properties with recurring acts of communication.

I co-authored an article on this in grad school… I’ll see if I can condense it into a reasonable blog post that doesn’t run afoul of copyright.

“The obvious example of this would be when content is repurposed, as when old government comics become items for entertainment, or when movie posters or album covers become art pieces. ”

I presume this is supposed to be obvious on the grounds that content doesn’t change over time? I think that’s not true though; context does in fact cause content to change, I’d argue. Hamlet means something rather different after centuries of canonization than it meant when it was first staged.

I think we’re talking past each other… Of course content changes over time, often as part of an effort to fulfill a different purpose (Duchamp signed his urinal, after all). I’m confused by the Hamlet example inasmuch as you’re using a claim about meaning to support an argument about content and purpose when, at least to my mind, meaning isn’t reducible to content, form, purpose, discourse community, etc.

The obviously was meant to convey that we take it for granted that, (at least sometimes), the form can be the same even when the purpose is different. Another example is irony, or any trope where the form of a written phrase is the same as the literal phrase but serves a different purpose. I realize that one could argue that each utterance is unique to the situation, a la Derrida, and therefore so too is the form. That actually seems fine if we’re talking at a high level of abstraction. Day-to-day, however, it seems like we’re pretty happy using form as a means to group things.