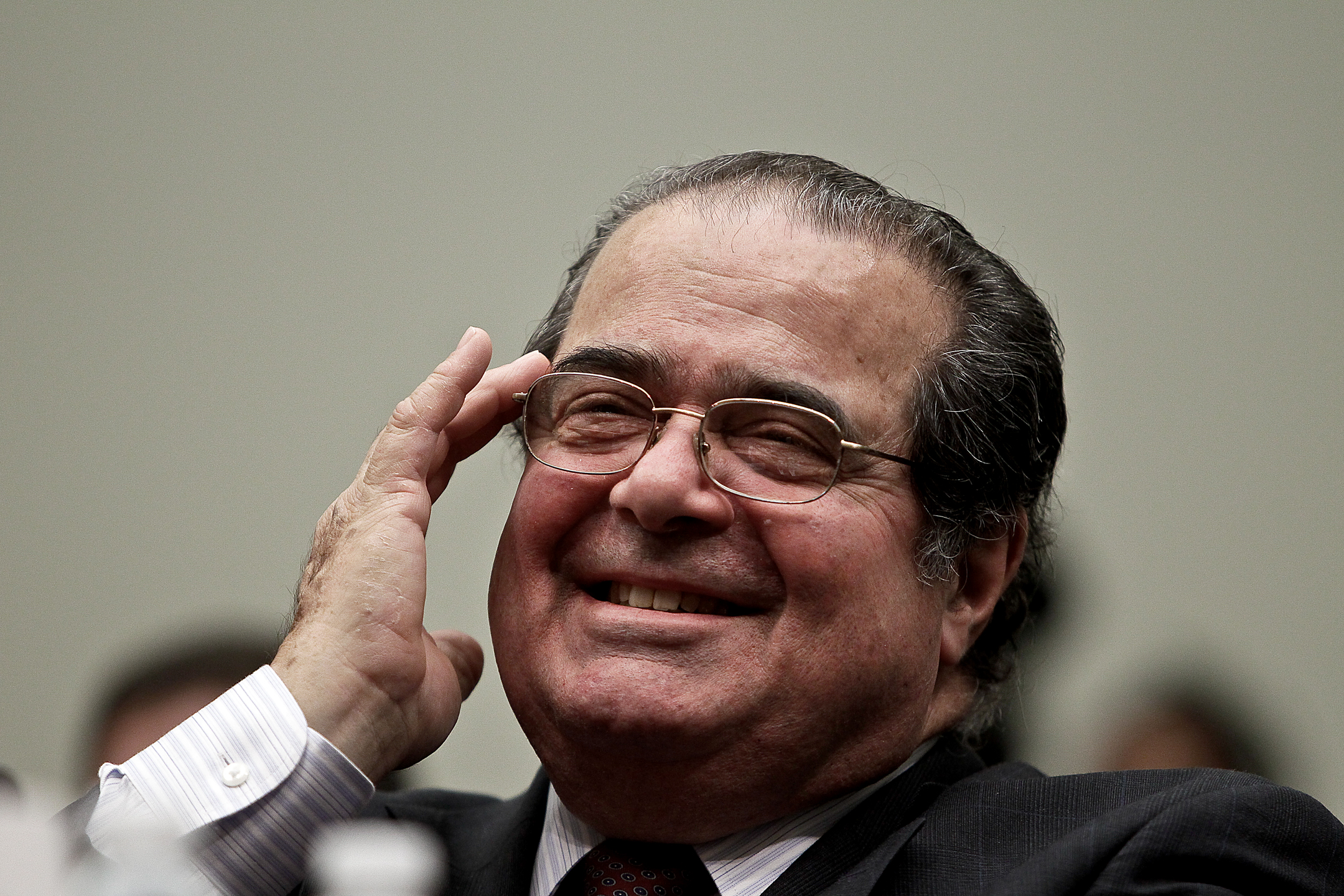

What can political science tell us about grief? Antonin Scalia’s death provoked a mixture of disgust and admiration that was covered extensively by American and international news media.

Some progressives were ready to list Scalia’s faults and argue that, even though dead, the man needed to be held accountable. Others, including some leftists, argued that condemning Scalia’s politics was disrespectful and tasteless. Death became a de-politicizing force that elevated Scalia above contestation, an ideological position that has historic support from philosophers like Hannah Arendt, who once argued that, “what makes a man a political being is his faculty of action.” The argument might go that Scalia, now deprived of his ability to enact politics in any space that could be called ‘the public sphere,’ had become a depoliticized object. But this position obscures how dead bodies are politically managed, with some dead bodies used to advance national identity and others being omitted from civic life. Death and grief aren’t apolitical.

Literary texts, at least, suggest that mourning can be a form of political expression. Texts like Antigone and the character of Ophelia from Hamlet illustrate how grief can either consolidate or subvert state power. When President Obama visited Scalia’s body “to pay his respects”, he also reinforced the idea that grief could be managed through public practice. But is publicizing grief necessarily wrong? I don’t think so, for reasons I’ll explain below, but there are certainly some articulations of grief that should make us wary.

Judith Butler, for example, warns her readers that highly ritualized styles of mourning, often supported by state and media, can produce moments where “critical modes of questioning are drowned out.” Butler, in particular, is interested in how grief for certain bodies can meet “social and cultural force of prohibition,” a conclusion she has reached by examining LGBTQ relationships and the institutional barriers that prevent couples from engaging in certain rituals of mourning. Think of hospital visitation rights, where a seemingly mundane waiting room becomes the space where grief is managed by bureaucratic processes. Certain persons become the recipients of national mourning, with all the material support this entails, and others have their grief consigned to the margins of society through legalistic manoeuvring.

We can extend these examples to world politics. Witness how grief is often used to advance nation-building projects and manage international conflict. Children, in particular, often figure as natural innocents and become strategic assets that are used to mobilize outrage. Take the death of Mohammed al-Durrah in 2000, a Palestinian child who was filmed hiding from Israeli gunfire with his father. His mother described his death as a sacrifice “for our homeland, for Palestine.” A PLO spokesperson told the BBC that the international community shouldn’t be surprised when children participate in spontaneous uprisings when “from womb to tomb, we are condemned to sub-human living conditions.” The Israeli Defence Force similarly condemned Mohammed’s death, but then blamed Palestinian militants, arguing that the “cynical use” of “innocent children” as human shields resulted in Mohammad’s death.

Certain deaths cultivate outrage, while others are met with shrugs. When Ben Norton asked last week, “[d]o French lives matter more?” he was contrasting Western rage at the ISIS attacks in Paris with the silence on attacks in Iraq, the deadliest the country has seen this year. Answering his own question, Norton writes: “The responses — or lack thereof — from Western media outlets, governments, and citizens makes their answer obvious.” In this moment, grief could have acted as a critical intervention to the way conflict in the Middle East is usually understood.

Alternatively, we see how the grief surrounding Alan Kurdi, whose death prompted international rage, pressured the EU into adopting a more favourable stance on refugee policy, indicating that public grief has the potential to, as David McIvor writes, cultivate “ethical dispositions towards human vulnerability that would make possible a less-violent politics.” Perhaps for this reason I’m hesitant to condemn public rituals of grief, since these rituals can produce grassroots movement. But the question of whose pain is validated has an answer rooted in the asymmetries of political power.

These are only a few examples that illustrate how grief is legitimized through political ritual. Mohammad al-Durrah’s body, for example, became a stage upon which two competing nation-building visions were articulated. Alan Kurdi underwent the same treatment, and the nearly universal outpouring of grief towards his death was then later subverted when Charlie Hebedo portrayed him as an Abuser-in-the-Making on its front cover. The message was clear: the humanitarian impulse towards refugee children was misplaced, since they’d grow up to be misogynists anyway. Scalia now faces similar treatment, with various factions competing to dominate the narrative that gives meaning to his death.

I’m not convinced that dead people can remain apolitical, or that being ‘apolitical,’ (translation: being silent) is even desirable. Attempts to dampen criticism about Scalia can reinforce an ‘official’ American identity, one that’s apparently dependent on conservatism in the judicial branch. Certainly, the Republican presidential nominees have used Scalia’s status as a “legal giant,” to quote Ted Cruz, to push forward their ideas about what America should be. At first, these words seem courteous and tasteful and so haven’t attracted scorn, but kind words aren’t automatically apolitical or non-strategic and commemoration can be a way of validating ideology. Scalia’s towering reputation, according to Jeb Bush, creates an onus on Obama to nominate someone with a “proven conservative record,” after all. And as any pacifist can attest, kindness and praise shouldn’t be conflated with an absence of politics.

Can criticizing Scalia create an alternative political vision for the United States? At the very least, Scalia’s critics counter the national vision offered by state officials and their supporters. Mourners should not be compelled to reproduce civic identity in a way that celebrates some lives, like Supreme Court Justices, and marginalizes others. Celebrate or condemn Scalia, but don’t pretend that one side has a monopoly on etiquette or exists outside of politics.

Great thoughts here… I hadn’t seen the Jeb Bush quote, which is just odious in its implications and assumptions.

It’s interesting, too, how second amendment fundamentalists invoke grief in the wake of mass shootings to stymie talk about gun control. “Don’t politicize tragedy.”

As to whether critique can function as an alternative political vision,there’s a good deal of scholarship in rhetorical theory, and specifically in the literature on civility, that speaks to that question.