If you’re wondering why you’re reading a bible study during this blog’s weekly schedule, you can blame Chester Brown for creating a commentary-entertainment on the role of prostitution in the Hebrew and Christian Bible.

For those who have spent the last few years living under a rock, let me begin by stating that the provision of professional sexual services has, in recent years, become of paramount importance in the artistic and political life of Chester Brown.

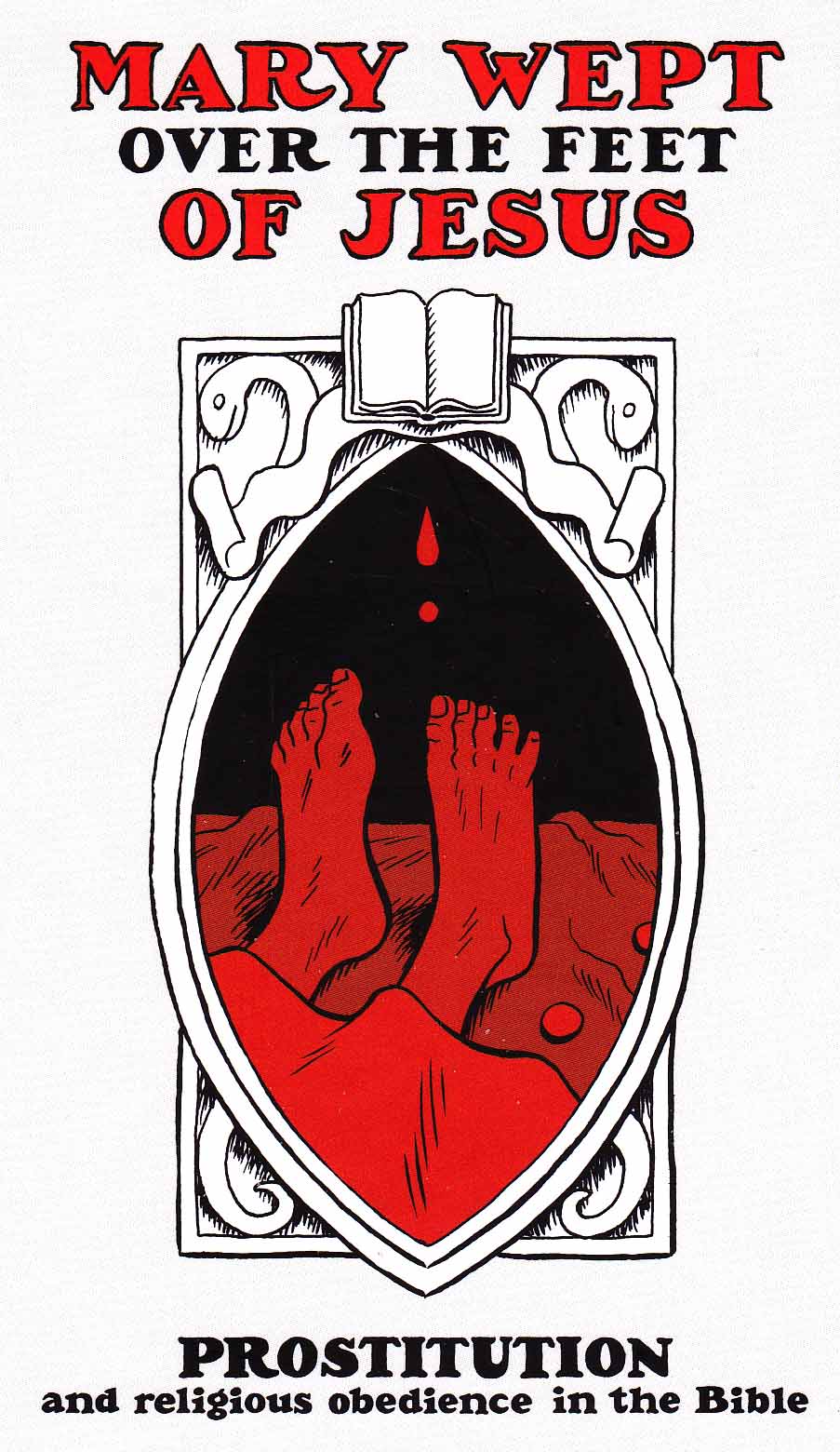

Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus is his hymn of praise and justification for a much maligned occupation. The Mary in question is Mary of Bethany from John Chapter 12, now conflated with the “sinful” woman of Luke Chapter 7:38 who wets Jesus’ feet with her tears. The cover to the new comic is as archly playful as Zaha Hadid’s vaginal design for the Al Wakrah stadium in Qatar. The image is a symbolic representation of female genitalia with Jesus’ feet acting as a symbolic penis and the Bible in the position of the clitoris.

It is an accurate representation of the comic itself—which is thoroughly unerotic and studious. Any ecstasies the reader might hope to derive from Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus will only be derived from a study of scripture.

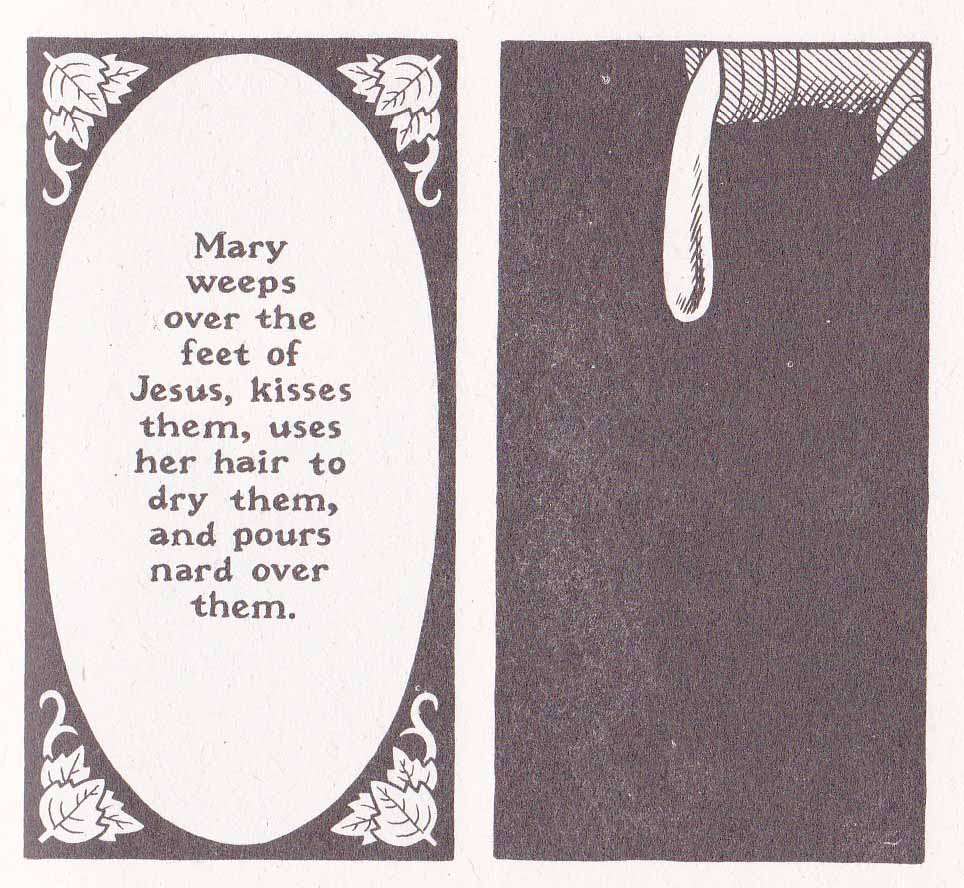

The art mirrors the earnestness of the endeavor and seems ground down into uniform shapes with all gnarly edges removed. Which is not to say that the work is devoid of imagination: there’s the God of Cain and Abel who is pictured as a naked giant with his back constantly turned to us, he holds Abel’s offering in the palms of both his immense hands; Mary of Bethany is only ever seen in silhouette and her actions disembodied into panels of darkness, her tear drops, and nard draining from an alabaster jar. We only see the angry reactions of the men surrounding Jesus. In so doing, Mary of Bethany becomes all the nameless women in the parallel stories found in the Synoptics but more than this, the entire anointment scene plays out as a metaphor for occult sexual intercourse.

Brown’s comic is concerned with the flexible and mercurial nature of the Hebrew and Christian God, the lack of fixity in his laws; and perhaps his occasional pleasure in those who flout them. If this seems at odds with what you’ve read about God in Sunday School, that would be because it is. Brown’s interpretation of the Bible has always been idiosyncratic, finding the nooks and crannies of hidden knowledge and, in the example which follows, not allowing facts to get in the way of a good idea (to him at least).

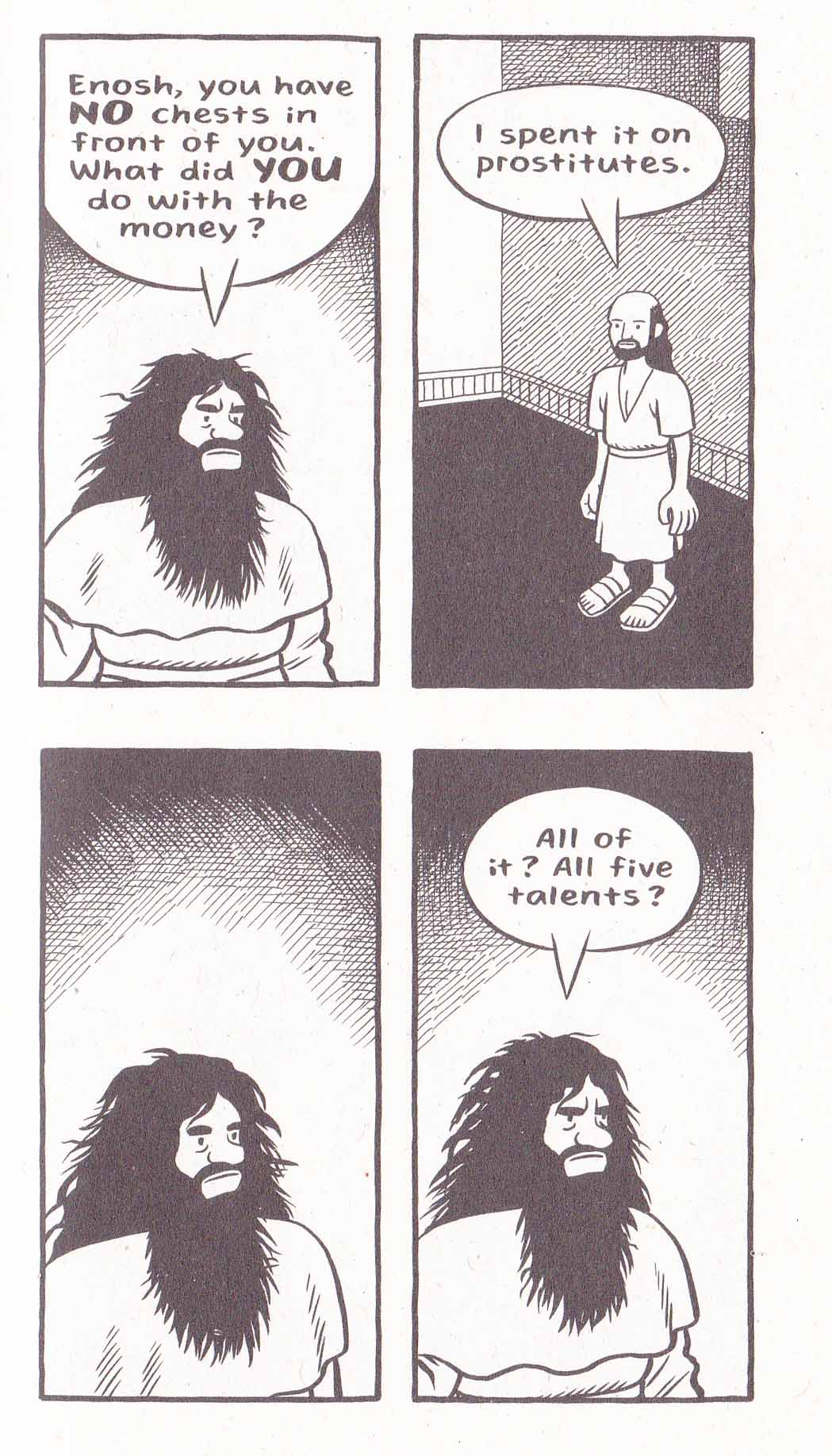

The central story of Mary Wept is “The Parable of the Talents.” This is one version which can be found online:

14 “Again, it will be like a man going on a journey, who called his servants and entrusted his wealth to them. […] 19 “After a long time the master of those servants returned and settled accounts with them. 20 The man who had received five bags of gold brought the other five. ‘Master,’ he said, ‘you entrusted me with five bags of gold. See, I have gained five more.’ 21 “His master replied, ‘Well done, good and faithful servant! You have been faithful with a few things; I will put you in charge of many things. Come and share your master’s happiness!’ […]

24 “Then the man who had received one bag of gold came. ‘Master,’ he said, ‘I knew that you are a hard man, harvesting where you have not sown and gathering where you have not scattered seed. 25 So I was afraid and went out and hid your gold in the ground. See, here is what belongs to you.’

26 “His master replied, ‘You wicked, lazy servant! … […] … 28 “‘So take the bag of gold from him and give it to the one who has ten bags. 29 For whoever has will be given more, and they will have an abundance. Whoever does not have, even what they have will be taken from them. 30 And throw that worthless servant outside, into the darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.’

(Matthew 25:14-30, NIV)

One problem with reading Brown’s copious notes is that they frequently communicate as facts that which is very much in dispute. To wit, in discussing “The Parable of the Talents”, Brown claims with a kind of divine certainty that “the work that we now call Matthew is a Greek translation of an earlier book that was written in Aramaic.” I suppose this represents the assurance of an artist who considers himself a kind of latter day Gnostic.

The idea that at least parts of the Gospel of Matthew was originally written in Hebrew is not a recent invention (see Papias by way of Eusebius) and is held by many Christians but hardly beyond dispute. There is as much reason to believe that this Gospel of the Nazareans (a names which appears only in the ninth century) is an Aramaic translation of Matthew (which is in Greek) or at least takes creative license and inspiration from that canonical book. This Gospel of the Nazareans has only survived in fragments brought down to us by various Church Fathers, and it is a summary of the Aramaic “Parable of the Talents” found in Eusebius’ Theophania (4.22) that provides Brown with his new reading.

From Bart Ehrman and Zlatko Plese’s translation of Eusebius’ paraphrase of “The Parable of the Talents” in Theophania:

“For the Gospel that has come down to us in Hebrew letters makes the threat not against the one who hid the (master’s) money but against the one who engaged in riotous living.

For (the master) had three slaves, one who used up his fortune with whores and flute players, one who invested the money and increased its value, and one who hid the money. The one was welcomed with open arms, the other blamed, and only the third locked up in prison.” [emphasis mine]

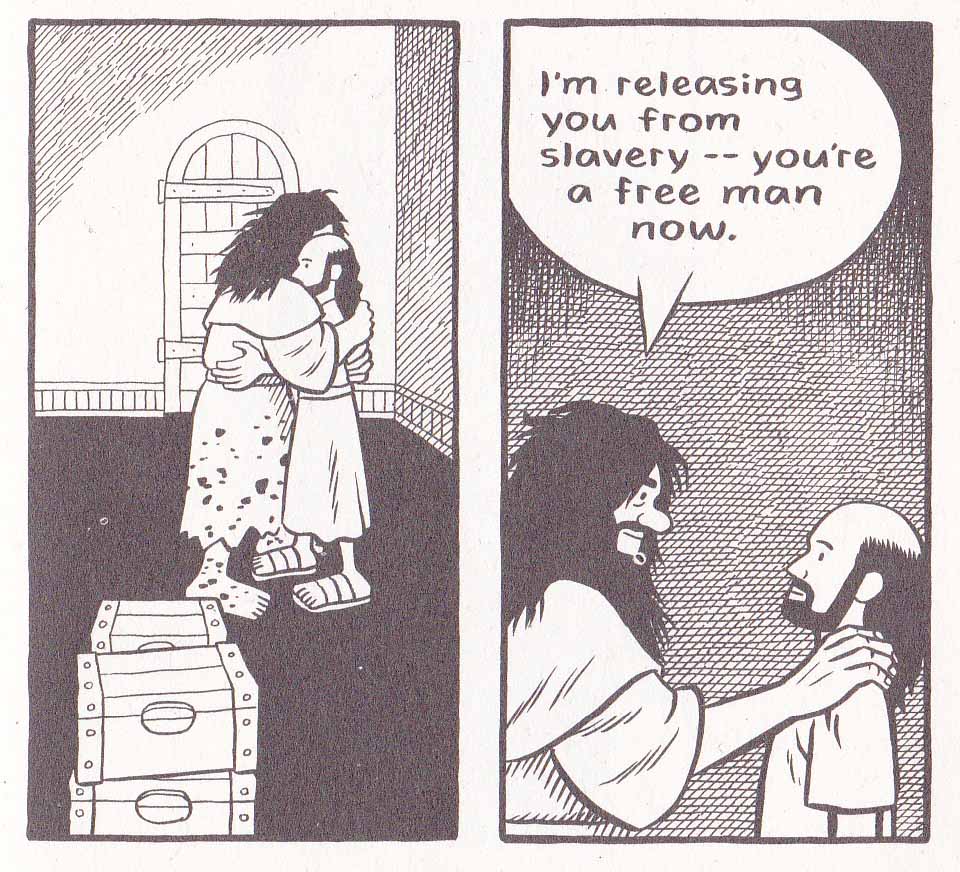

In his quotation of Ehrman in his notes, Brown deliberately leaves out the first section of Eusebius’ summary—that it was the servant who “engaged in riotous living” (i.e. the one who used up his fortune with whores and flute players) that was cast into the outer darkness with the concomitant weeping and gnashing of teeth. In so doing, he elevates the position of that servant in his retelling. In the original text, Eusebius quite clearly excuses the servant who hides the master’s money but in Brown’s rhetoric, it is the “whoring” servant who is rewarded

Brown cites John Dominic Crossan’s The Power of Parable as the primary source of his inspiration with regards his interpretation of “The Parable of the Talents” but while Crossan does provide the same reduced quotation from Eusebius, he obviously knows the whole and is clearly at odds with Brown’s reading:

“The version of the Master’s Money was presented in elegant reversed parallelism—a poetic device…But that structure means that that, of the three servants, the squanderer is “imprisoned’…The hider is, in other words the ideal servant.” (Crossan)

For Crossan, the parable is primarily about the conflict between the “Roman pro-interest tradition” and the “Jewish anti-interest tradition”; a challenge to live in accordance with the Jewish law in Roman society. Brown’s adaptation, on the other hand, seems to have been constructed out of whole cloth. If Brown’s adaptation of the “Parable of the Talents” has no historical or textural basis, then what are we to make of it? Perhaps Brown sees himself as a kind of mystic who has divined the true knowledge and the error in Eusebius’ (and presumably Crossan’s) prudishness.

More importantly, why would Brown even require a Christian justification for prostitution? Brown provides the answer to this in his notes—he considers himself a Christian though an atypical one. Moreover he considers secular society’s disapproval of prostitution (“whorephobia”) an unjustifiable legacy of poor Biblical interpretation, not least by a rather inconvenient person called Paul. Brown lives in Canada where it is illegal to purchase sexual services but technically legal to sell them. In this Canada has adopted the longstanding Swedish model, of which The Living Tribunal of this site (aka Noah) has grave misgivings, mostly because sex workers report that it puts them at risk.

Brown uses the story of Jesus’ anointment at Bethany to highlight the vulnerability of women in Jesus’ time. The title of Brown’s comic is a reference to the story told in Luke 7:36-50 where a (nameless) woman in the city “who was a sinner” bathes Jesus’ feet with her tears, drys them with her hair, and anoints them with ointment. The story has parallels with the story of Mary of Bethany’s anointing of Jesus’ feet in John 12:1-8, and Mark 14:3-11 where an unnamed woman pours expensive nard on Jesus’ head (“Truly I tell you, wherever the good news is proclaimed in the whole world, what she has done will be told in remembrance of her.”)

After a period of vacillation, Brown has come down firmly on the idea that the woman in question (Mary of Bethany included) was a prostitute. By his estimation, the various versions of this story are not redactions retold for different ends but the exact same story from which the individual elements of each can be combined to form a richer more instructive whole.

Feminist interpretations of Luke (among others) differ greatly on this subject. The evidence for the woman’s sexual sin tends to come down to her exposure of her hair in public, her intrusion into the house of Simon, and her description as a “woman in the city”— all of these points have met with equally forceful rebuttals in recent years. These feminist readings focus on the sexualization of the woman and the fixation on her sin. They question scholars “who choose predominantly to depict her as an intrusive prostitute who acts inappropriately and excessively” despite the gaps in Luke’s text which allow a variety of readings. It is these gaps which opens this famous episode to a variety of rhetorical uses.

One of the great feminist readings of the New Testament, Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza’s In Memory of Her, concerns itself with the historical erasure yet centrality of women in the Gospels. At one point, Martha (Mary’s sister) is seen as a candidate for “the beloved disciple” when John places the words:

“Yes, Lord, I believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one coming into the world.” (John 11:27)

…into the mouth of Martha as the climatic faith confession of a ‘beloved disciple’ in order to identify her with the writer of the book. To Fiorenza, Mary’s action of using her hair to wipe Jesus’ feet is “extravagant” and draws comparisons to Jesus’ own washing of his disciples’ feet in The Gospel of John. Also of note is the decidedly male (Simon, the disciples, Judas) objection to her actions in every instance which is rebuked by Jesus.

While most sex workers are in fact women, Brown seems less interested in recovering the central status of women in the Bible. He has a somewhat different feminist (?) mission. Is it possible to be a sex worker and still be a good Christian? Even Brown seems to admit that it is impossible to reconcile prostitution or any form of sexual immorality with Biblical laws and Jesus’ admonitions. His new comic simply charts the curious areas where the profession turns up in the Bible and where its position in that moral universe is played out most sympathetically. While Jesus commands the woman taken in adultery to go and sin no more, I know not one Christian who has not continued to sin in some shape or fashion. Shouldn’t we be exercised about our own sins before those of perfect strangers? One would have to posit that the sin of sexual immorality is greater than all other sins (including our own) for one to be primarily concerned about its deleterious effects.

Brown’s position as a Christian in Mary Wept is that God’s laws are not immutable. Instead of a life of submission to curses and obedience to laws, he has chosen the “life of the shepherd” as espoused in Yoram Hazony’s The Philosophy of Hebrew Scripture:

“…a life of dissent and initiative, whose aim is to find the good life for a man, which is presumed to be God’s true will.”

For Hazony, piety and obedience to the law are “worth nothing if they are not placed in the service of a life that is directed towards the active pursuit of man’s true good.” One presumes that Brown feels that he has found “man’s true good” in the sexual and personal freedoms afforded by prostitution. Whether he has found woman’s “true good” remains a far more controversial question.

In a highly original move, Chester Brown selectively interprets the bible to support existing political commitments.

Seriously, though, I’m glad Suat did the work necessary to evaluating the claims made in the book. I just hope that Brown’s arguments don’t take attention away from people with more nuanced accounts about the cultural and economic issues confronting sex workers.

Also, did anyone else catch the Craig Thompson pull quote:

“The Bible is Chester Brown’s holy harlot. He plumbs the mysteries of her depths while she schools him in the ways of love. Like all of Chester’s work, this book is confounding, yet addictive, instantly re-readable, and expands with revelations in his hundred pages of notes. A work of passion, research, and elegant clarity. My new favorite.”

Yikes.

Good lord; that quote could almost be satire.

The question is, Suat, forced to choose, do you pick this or Crumb’s Genesis?

I think the new comic stands less chance of adding to the conversation than the previous one. Is the Christian bloc that relevant in Canada on the issue of prostitution? It seems to me he’s working out more personal-religious issues. It’ll probably be seen in years to come as one of those funny-castigating books about the Bible (of which comics has a long tradition). I don’t think this was Brown’s intent but my guess is that’s probably how it will all work out.

As for Craig Thompson – everyone sounds gushy in blurbs right? Maybe he has a new favorite every month?

I can hardly remember Crumb’s Genesis. The Chester Brown comic seems much more vested in the issues it’s discussing. More carefully thought out if quite obviously wrong in a few parts. Crumb’s thing seems like just another illustration job – more populist and almost conservative. Brown’s comic is probably more clever and interesting to read. At least it makes you think (?)

I’d just stick with a prose commentary to be honest. Why choose?

This is an interesting article and i guess you cant blame Suat for arguing that way as Brown seems to try and justify his interpretation as earnest bible study and maybe even as a political instrument (does he? havent read his notes yet). But for me art really is above all that. Maybe Alan Moore’s take on Charlton superheroes was ‘obviously wrong in a few parts’ too but i really didnt mind. Or remember Osvaldo Oyola’s article on here about The Killing Joke? If Batman is this unintentional queer icon, why couldnt the bible be read as pro-sex work?

I also had to compare it to Crumb’s Genesis, and I agree with Suat (Crumb doesnt really have that much to say). I was already a big fan of Brown’s Jesus stories published in Underwater, as his dark, tall and angry Jesus was a character that made so much more sense than the version you grow up with in our culture.

“The question is, Suat, forced to choose, do you pick this or Crumb’s Genesis?”

How about this or Sim/Gerhard’s Latter Days?

I think this book is far more interesting than Crumb’s scripture adaptation—-and I like it much better than Chester’s Paying for It, which I slagged mercilessly on this site a while ago. Mary Wept Over the (Penis) Of Jesus is a gorgeous little package, with some very appealing, concise art that for some reason brings to my mind the more cartoony Plop-era Wally Wood. As I love Chet’s earlier, unfinished biblical visualizations of in the back of Yummy Fur, so I appreciate his revisionist approach in this case to a book that has been deliberately misread and distorted by unscrupulous (male) scumbags for many centuries, for far more devious aims than Chester’s stated goal of defending prostitution. Well, the book seems also to buttress libertarian views and some potential more feminist interpretations are left out of the author’s copious and fascinating notes, but those points are still there to be read into what he did and the book certainly doesn’t dehumanize the female characters the way Paying for It did, quite the opposite. Still, I don’t have the chops in terms of knowledge of the depicted sections of the bible to agree with, or to dispute, Suat’s comments here.

Hey, James, haven’t seen you in these parts in some time. So nice to hear from you. I don’t disagree with most of that. Better than Crumb, comparable to his earlier Biblical work, more sensitivity to female characters. At the very least, Brown has something to say and isn’t just an illustrating machine.

Suat,

You focus on my decision to omit a passage (which I will henceforth call The Omitted Passage) from Eusebius’s summary of the Nazarean version of The Parable Of The Talents. I want to address your interpretation of The Omitted Passage and your (probably unintentional) implication that I was being deliberately deceptive in omitting it.

Here’s The Omitted Passage again:

“For the Gospel that has come down to us in Hebrew letters makes the threat not against the one who hid the [master’s] money but against the [whoremonger].”

Your interpretation of The Omitted Passage is that it’s saying that the master punishes the whoremonger-slave and rewards the-slave-who-hid-the-money. But take another look at The Omitted Passage. It actually does not say that the master “makes the threat” against the whoremonger, it says that The Gospel Of The Nazareans makes the threat. The Gospel Of The Nazareans and the master are not the same thing. The Gospel Of The Nazareans was a book. The master is a character who appeared within that book. A character within a work can say and do things that are at odds with the message of the work. Despite the presence of Iago in Shakespeare’s Othello, that play’s message is not that one is supposed to encourage murderous jealousy in others. And it’s important to keep in mind that a work’s message can be misinterpreted.

In my opinion, things went something like this: Jesus told a parable in which a slave-master embraces a whoremonger slave and punishes a slave who hides money. That parable was accurately recorded in The Gospel Of The Nazareans. Eusebius saw that version of the parable and incorrectly interpreted the master and the whoremonger as characters Jesus disapproved of. Eusebius therefore saw those two characters as “threatened” (by damnation).

You mention that John Dominic Crossan also omitted The Omitted Passage in his discussion of the parable, even though you believe it bolsters his interpretation. I think you’re wrong. I think Crossan left out The Omitted Passage because he could see that it lent itself to multiple interpretations and that it was therefore irrelevant to the point he was trying to make. That’s also why I left it out. On top of that, explaining all of the foregoing would have made an already long notes section even longer. No deception was intended.

Suat, you don’t mention that after Eusebius’s summary of the Nazarean version of the parable, he added a further relevant sentence that I also did not include in Mary Wept. Eusebius wrote:

“As for the last condemnation of the servant who earned nothing, I wonder if Matthew repeated it not with him in mind but rather with reference to the slave who caroused with drunks.”

That seems pretty clear to me. Eusebius is saying that the slave (or servant) who hid the money (and earned nothing) is, in the Nazarean version, condemned and that Matthew repeated the condemnation in his gospel. Therefore, the whoremonger is rewarded, and my interpretation is correct. I’ll confess that I don’t know what Eusebius is talking about at the end of the sentence. I can’t recall a parable in which a slave hangs out with drunks. Is my memory faulty? Maybe Eusebius is referring to something other than a parable. Perhaps you have a theory. If so, I’d be curious to hear it. Nevertheless, I think you’ll have to agree that the sentence vindicates my interpretations of both the Nazarean version of The Talents and The Omitted Passage.

I don’t think you were being deceptive in neglecting to mention that further sentence. I think you didn’t know about it. I didn’t know about it until about two months ago, when I read James Edwards’ 2009 book, The Hebrew Gospel And The Development Of The Synoptic Tradition, which the above translation of The Further Sentence is from. (That translation can found on page 64 of Edwards’ book.) (The work that I call The Gospel Of The Nazareans is called The Hebrew Gospel by Edwards.) I wish I’d read Edwards’ book while I was working on Mary Wept since it provides more reasons for assigning an early date to The Gospel Of The Nazareans. Edwards also (on page 65) confirms the link I made between the The Talents and The Prodigal Son, calling the whoremonger-slave “a mirror image of the prodigal younger son”. It’s worth reading if you’re as interested in the subject as you seem to be, Suat.

There IS an error in Mary Wept regarding Eusebius. On page I76, I wrote that he “lived from about 240 to 340”. That was a transcription error. He was actually born around 260.

As for those of you who are saying that Mary Wept is better than Robert Crumb’s Genesis: I would be lying if I said that there isn’t a part of me that’s pleased to hear that, but I’m not proud of that part of myself. The original biblical Genesis is one of the great works of literature. It was adapted with intelligence and care by Crumb, a master of the comics form. His drawings for it are among the best of his impressive career. Crumb’s Genesis is an amazing book. Perhaps Mary Wept is more entertaining on a superficial level, but I think it’s a mistake to compare the two works, although I understand why readers will.

Hey Chester. Thanks for commenting!

We had a long roundtable on Crumb’s Genesis. I don’t think anyone doubts the importance of Genesis as literature, or Crumb’s skill as a draftsman. But there were some questions about whether he brought much in the way of a fresh perspective, or a strong point of view, to the project.

Hi Chester, and thanks for the detailed reply.

I think I understand how you came about your interpretation of the Nazarean Parable of the Talents. But let me rephrase your points just In case I’ve got things wrong.

I gather that in your opinion, the first sentence in Eusebius’ paraphrase is largely (?purely) interpretation, while the latter part represents the summary proper. If you do visit these parts again, you can tell me if I’m wrong in this.

I think that’s one possible way of looking at things but my feeling is that the first sentence is part of the summary. At the very least we should be able to deduce the whole of the Nazarean Parable from Eusebius’ statement that:

“…the Gospel that has come down to us in Hebrew letters makes the threat not against the one who hid the (master’s) money but against the one who engaged in riotous living.”

Since Eusebius is our only source (at present) for the Nazarean Parable, the most obvious reading is that Eusebius did read the much longer whole and has provided its ultimate judgement. The assumption here is that the first sentence of the paraphrase reflects a more detailed exchange in the full text of the Nazarean Parable (where things are presumably much clearer) similar to that in the Greek Gospel of Matthew.

I will state here that I categorically *don’t* think you’re lying or being deliberately deceptive. It’s just that your reading of Eusebius requires latter day readers to jump through an extra hoop and assume faulty interpretation on his part. Which is problematic since he is our only source for the Nazarean Parable. And Eusebius doesn’t seem to have much reason for being clouded in his reasoning.

I say problematic but not impossibly so. Our source for certain Gnostic ideas/books can sometimes only be found in the rebuttals of those Church Fathers most antagonistic towards them. But the Gospel of the Nazareans doesn’t exactly fit the bill as far as Eusebius is concerned. He would not have summarized it unquestioningly if he considered it heretical.

As for John Dominic Crossan leaving out the first sentence of Eusebius’ summary, I do think he derives his interpretation of the Nazarean Parable from the entirety of Euesbius’ summary (as well as its correspondence with the Greek Matthew). Because your distinct reading of the Parable of the Talents is the most obvious one without recourse to Eusebius’ first sentence.

I was also quite unaware of the extended version of Theophania 4.22 since I’ve only read the fragment translated in the Ehrman/Plese book. But I serendipitously linked to the Google Books copy of James Edwards longer quotation in the above article without reading it through (see main article):

“As for the last condemnation of the servant who earned nothing, I wonder if Matthew repeated it not with him in mind but rather with reference to the slave who caroused with drunks”

In any case, thanks for bringing it to my attention. I do believe there’s another way of reading it though. Eusebius in that last sentence is referring to the more famous Greek Matthew – he is no longer referring to the “Gospel that has come to us in Hebrew characters” in that sentence.

What Eusebius is saying is that he believes that Greek Matthew’s condemnation of the servant who earned nothing was “repeated…not with him in mind but rather with reference to the slave who caroused with drunks.” (Matthew 25:25-26) Eusebius is trying to reconcile the two versions of The Parable of the Talents (the Nazarean Parable and the Greek Matthew versions; setting aside the Lukan one). I presume Eusebius does so because he believes that the Nazarean Parable antecedes the Greek version.

And doesn’t James Edwards’ state at the end of his own discussion of the Nazarean Parable that “both lexically and thematically, Eusebius’ quotation of the Hebrew Gospel in Theophania 4.22 bears an unmistakable relationship to the Gospel of Luke, and particularly to the parable of the Prodigal Son”? It seems like Edwards doesn’t find any thematic differences between the Nazarean Parable and Greek Matthew’s version.

I still don’t think your interpretation of the Nazarean Parable of the Talents is the most accurate one but I don’t think the best reading necessarily makes for the best art. But I also understand there’s a deeper motivation in the project and “Mary Wept” is a kind of personal commentary and journey of discovery. If so, our differences in opinion can be put down, as always, to the mystery of interpretation.

Finally, it is inevitable that we should compare your new comic and Crumb’s Genesis. I’m not suggesting that the latter is empty and devoid of value. What I’m suggesting is that you seem to have thought longer and harder about what you’ve adapted. There is very little doubt that you’re more passionate about the material. The comic is personal and it shows.

Chester,

Is there’s a chance your gospel adaptions from Yummy Fur/Underwater will ever be reprinted as a collection? Think it would be worth it, even as an unfinished fragment … I know I can’t be the only one waiting for this book :)

Suat,

Of course, you’re right — the slave who caroused with drunks is the whoremonger-slave. I’m kicking myself for missing the obvious. I was so focused on the whoremonger-slave as a whoremonger that I missed that Eusebius would have seen “riotous living” as involving alcohol along with prostitutes. That’s probably a revealing slip-up on my part.

Let me see if I’m understanding you — in that last sentence, Eusebius asserts that Matthew is repeating something. I think Eusebius believed that Matthew repeated the condemnation of the-slave-who-hid-the-money from the Nazarean version. Are you saying that Eusebius is referring instead to the repetition of the condemnation in Matthew? (I suppose one could say that Matthew repeats the condemnation. The slave is condemned in verse 25:26 and then again in 25:30.) Perhaps that’s possible, but I see my suggestion as more likely.

Incidentally, I’m guessing that, in order to understand what Eusebius wrote, you did what I did and went to the online English translation of the complete text of Theophania (at preteristarchive.com) in order to read section 4:22 in context. If you did, you found what I did — that the online version is Samuel Lee’s 19th century translation, that section 4:22 in that translation is considerably shorter than the surrounding sections, and that the summary of the Nazarean version is not in it. Someone, presumably Lee, censored the text. It would seem that Lee interpreted the summary of the parable the way I did. If he thought a more “innocent” reading was probable, then surely he would have fully translated 4:22 and explained the “innocent” interpretation in a footnote. That doesn’t prove that my interpretation is correct, but it does suggest that it’s not as odd as you seem to think it is.

Yes, Edwards sees a connection between The Prodigal Son and the Nazarean version of The Talents, but I would contend that that supports my point, not yours. If I’m right, then an authority-figure (symbolizing God) embraces a whoremonger in both parables. They both, then, have a similar structure and theme.

Tim,

I seem to recall that, many years ago, Suat wrote a negative review of the gospel adaptations I did in Yummy Fur and Underwater, and I agree with his general assessment of that material. (I can’t say that I agree with the specifics since I never read the whole piece.) I’d prefer it if that work wasn’t reprinted.

Chester, sorry to hear that. I kind of expected this answer I guess, and I would be curious to know why exactly you are now unhappy with the adaptions. Do you feel it was a disrespectful or incorrect way to handle the material? It’s just odd to me, as it was definetely one of the most impressing comics of my youth. Anyway thanks for your response, looking forward to whatever you’re going to work on next!

Actually, I found Suat’s old review in the archive and I guess it kind of answers my indiscreet questions. I think I haven’t seen much of the adaptions of Mark in Yummy Fur, but I was always very fond of Matthew, so I’m glad at least i still have my old copies of Underwater.

Chester,

Yes, I think Eusebius is “referring instead to the repetition of the condemnation in Matthew.”

In other words, (according to Eusebius) Greek Matthew lifted (repeated) the condemnation in the Nazarean Parable (of the one who engaged in riotous living) but applied it incorrectly to the one who hid the money. But I can see where you’re coming from obviously.

As for The Prodigal Son, I know you realize that the traditional version of The Prodigal Son doesn’t really support your case. I also know your comic adaptation has the father say, “You don’t understand…I love you BECAUSE of what you did, not DESPITE IT.”

But the more famous version has the father saying, “…for this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found!’ It’s not terribly supportive of the lifestyle of the son who “squandered his property in dissolute living.”

I’ve read your Afterword and know that you see a connection between The Parable of the Talents and The Prodigal Son; and that your impression is that Luke censored his version. But is there a historical/textural basis for this apart from your gut feeling? The Prodigal Son is from the hypothetical L-Source for Luke and there isn’t a corresponding Nazarean Gospel for it. Or at least I haven’t heard of one (not being a Biblical scholar and all that).

And, yes, I did look up all the online versions of the English translation of Theophania and all of them (including a downloadable PDF) are by Samuel Lee. It also seems like his “complete” translation is the primary one that exists on Amazon.com as well.

I really have no idea whether the Lee translation was censored, badly/selectively translated (which is all too common), whether he had an incomplete copy of Theophania from which to translate or that I’m just looking in the wrong part. And since I don’t understand Greek, I’m just as stuck as you are.

I will say that the translator, Samuel Lee, is decidedly of a particular bent and is not convinced of the worthiness of the Hebrew/Nazarean Gospel. You can see in his footnotes some telling remarks on an earlier citation by Eusebius of that Nazarean Gospel (footnote 33):

“It may be remarked, that Eusebius does here cite this passage as worthy of credit, although he does not ascribe any divine authority directly to it. Mr Jones has, in his very excellent work on the Canon of the New Testament, affirmed that Eusebius had never so cited this Gospel–which, indeed, had not appeared in the then known works of Eusebius. Still, this cannot be adduced, as in any way affecting the character of our acknowledged Gospels. I am very much disposed to think with Grotius, &c. that this was the original Gospel of St. Matthew, greatly interpolated by the heretical Jews who had received it.”

Judging by that last sentence, it’s not hard to believe that he did excise sections having to do with the Nazarean Gospel. I guess what we need here is a Greek scholar and not some biased translator.

Tim,

Creating those Yummy-Fur/Underwater adaptations was part of my process of learning about the gospels and coming to understand them on a deeper level. (Suat would probably disagree that my understanding is deeper.) While I had some knowledge of the gospels when I began adapting them, that knowledge was pretty shallow. I feel that I’d do a much better job now. Also, the artwork in most of my version of Mark is poor. I did a better job in drawing Matthew.

Suat,

No, I’m not basing my version of The Prodigal Son on a little-known, extra-biblical text — just, as you say, on “gut feeling” and for the reasons given in the Mary Wept notes. (Particularly the point that the father’s supposed love for the older son doesn’t match his actions when he neglects to invite that son to the feast.) We do know that the gospel writers changed other parables. (Compare, for example, the two versions of The Parable Of The Great Banquet in Matthew 22:1-14 and Luke 14:16-24. One or both of those gospel writers must have changed the story. A biblical literalist could argue that Jesus told the parable both ways, but most biblical scholars would agree with me on THIS matter, if not others.) So, it seems valid to speculate on how a parable might have originally been told if one has reason to think that it was changed by a gospel writer. And I think (as I say in Mary Wept) that a comparison of the Nazarean version of The Talents with The Prodigal Son gives us legitimate reasons for thinking that the latter was altered.

Well, tomorrow I’ve got to go to the next stop on my signing tour and won’t have time to engage in this exchange any further, so I’ll leave the last word to you (if you want it). I’ve enjoyed the discussion and actually learned something. (I’m embarrassed to think about how much time I spent puzzling over who the-slave-who-caroused-with-drunks was, while it was immediately obvious to you.) Thanks. And I’m sure you weren’t the only person who noticed the absence of The Omitted Passsage, so it’s good that your review gave me a reason to address the subject.

Chester, thanks again for taking the time to respond. I hope next time someone does a big interview with you (hello TCJ), you would have a chance to get into this, i.e. your better understanding of the gospels and how these old adaptions don’t do it justice. It’s just kind of weird being a fan of a work that’s now dismissed by the author … Well I’m glad Clowes never decided that Ghost World sucked or something :)

Chester,

Thanks for the clarifications on The Prodigal Son comics adaptation. The Parable of the Great/Wedding Banquet doesn’t seem like a particularly helpful comparison since the general thrust of the versions in Matthew and Luke appear to be the same though the specifics vary. But I get what you’re saying and how you feel it relates to the Cain and Abel story (?) where obedience seems to be taken for granted.

I know that you were probably joking in your remarks to Tim but there’s little doubt that there’s a significant difference in depth if you compare your adaptation of Mark and the current comic.

Good luck on your signing tour!

Pingback: 05/10/2016 – Comics Workbook

Since, over on The Beat, Heidi MacDonald misunderstood something I wrote in the above exchange, I’ll clarify that point here. In acknowledging that Suat’s identification of the slave mentioned in The Further Sentence was correct, I was not conceding the larger point. That is, I stand behind my assertion, as made in Mary Wept Over The Feet Of Jesus, that the master embraces a whoremonger in the original version of The Parable Of The Talents.

This was great, not least for Chester Brown’s gentlemanly intervention. And Suat is one of the few comics critics whom I could imagine taking on this book at this particular level. I’ve written some more general thoughts over at The Comics Journal.

Here, http://www.tcj.com/praying-for-it/

Pingback: Chester’s Christian Comics | The Smart Set