This is part seven of our look at comics, cartoons and language– today focussing on Britain

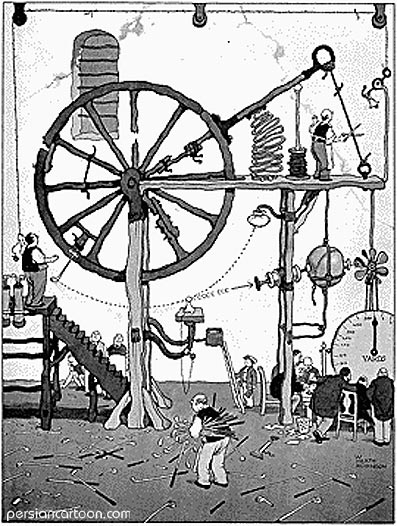

Art by Heath Robinson

Britain has a long, rich tradition of cartooning second to no other land’s. And, as we saw for American English, cartoons have contributed to the country’s popular language.

Some American cartoon coinages have crossed the Atlantic, such as ‘keeping up with the Jones’s’. But others are purely British. Where America has Buck Rogers and Rube Goldberg, Britain has their equivalents Dan Dare and Heath Robinson.

It’s appropriate to start with the cartoon symbol of Britain.

O what has made that sudden noise?

What on the threshold stands?

It never crossed the sea because

John Bull and the sea are friends;

But this is not the old sea

Nor this the old seashore.

What gave that roar of mockery,

That roar in the sea’s roar?

The ghost of Roger Casement

Is beating on the door.John Bull has stood for Parliament,

A dog must have his day,

The country thinks no end of him,

For he knows how to say,

At a beanfeast or a banquet,

That all must hang their trust

Upon the British Empire,

Upon the Church of Christ.The ghost of Roger Casement

Is beating on the door.John Bull has gone to India

And all must pay him heed,

For histories are there to prove

That none of another breed

Has had a like inheritance,

Or sucked such milk as he,

And there’s no luck about a house

If it lack honesty.The ghost of Roger Casement

Is beating on the door.

I poked about a village church

And found his family tomb

And copied out what I could read

In that religious gloom;

Found many a famous man there;

But fame and virtue rot.

Draw round, beloved and bitter men,

Draw round and raise a shout;The ghost of Roger Casement

Is beating on the door.

— William Butler Yeats, The Ghost of Roger Casement

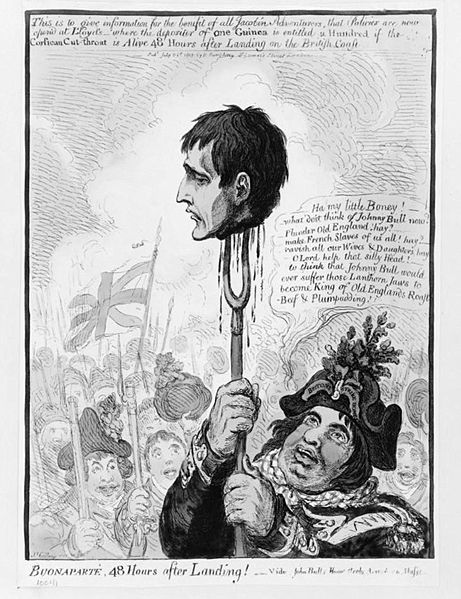

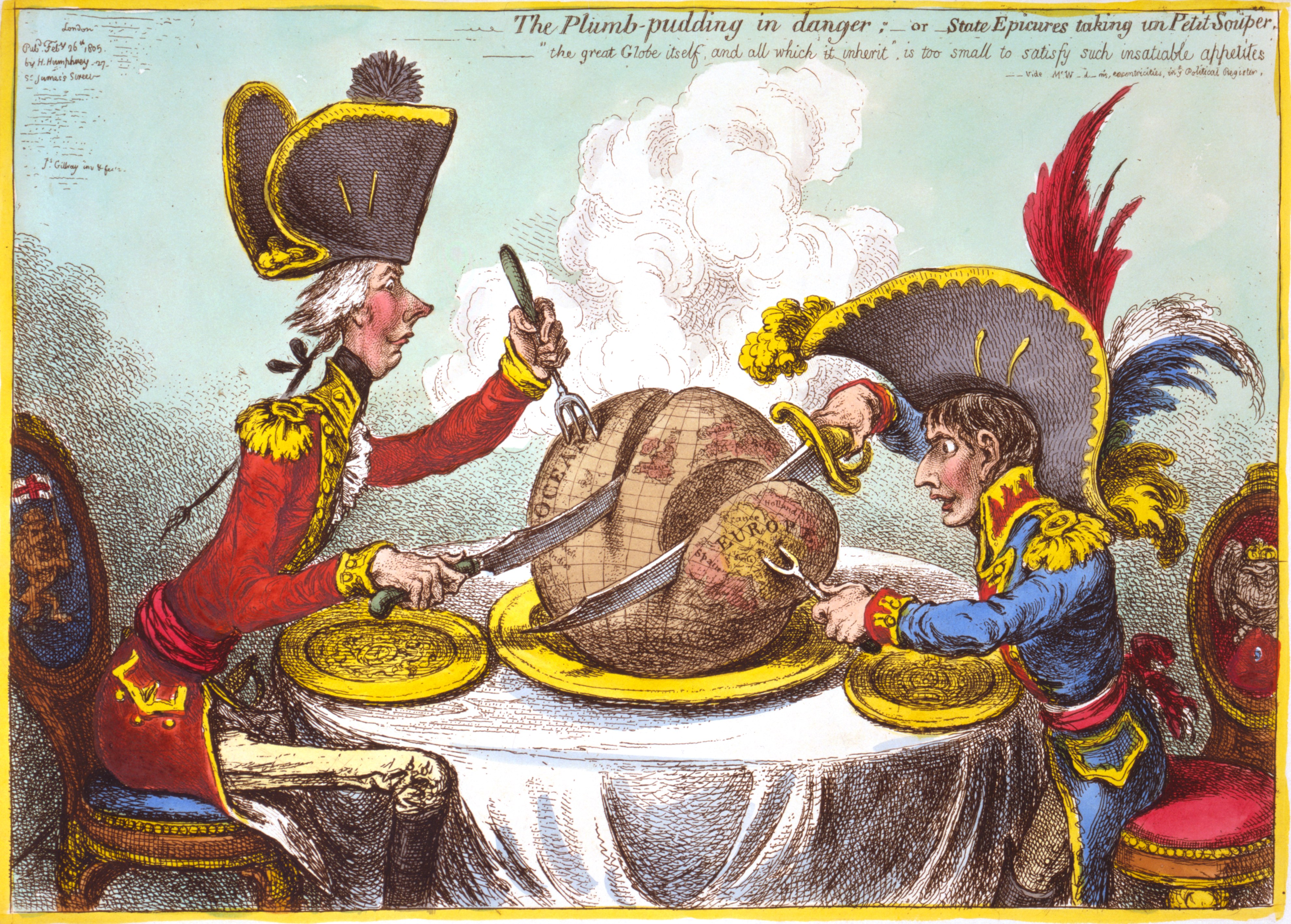

Art by Gillray: John Bull devours the french fleet

John Bull was created in 1712 by the satirist John Arbuthnot (1667 — 1735) in a pamphlet, as the personification of England. Cartoonists swiftly took to the character.

His appearance took a while to be fixed: at first, he was often depicted as an actual bull:

Soon, though, his familiar appearance as a stout, bluff squire came to be shaped.

(Above: John Bull making short work of Napoleon!)

By the 19th century, John Bull had been extended from personification of England to that of Britain and the British Empire: thus the Union Jack added to his waistcoat:

Of course, John Bull often interacts with other national symbols– notably Uncle Sam; whether in friendliness…

Art by John Fischetti

or suspicion…

Today John Bull is still used in speech to mean Britain; however, by no means always in a positive light, as the Yeats poem quoted above shows.

” Nigel’s been squandering his inheritance as fast as he can…that sort of rake’s progress cannot end well.”

William Hogarth (1697– 1764) was a painter and engraver of immense popularity– perhaps the first media superstar.

He has also contributed to the language. The series of paintings (later engravings) A Rake’s Progress detail the story of Tom Rakewell, a young heir who loses his fortune to drink, gambling, and whores, ending up in an insane asylum.

Since then, a rake’s progress has described a life of debauchery, sometimes with teasing irony.

+++

“So you’re tying the knot with Miss Moneybags, eh? Marriage à la mode, old chap– eh?”

Another series, Marriage à-la-Mode, satirises marriage for money, with a penniless aristocrat wedding the daughter of a rich miser:

A mercenary marriage came to be known as a marriage-à-la mode.

+++

“I wouldn’t go there after dark. It’s Gin Lane, mate.”

In the 18th century, the cheap spirit gin was a national scourge. ‘Drunk for a penny, dead drunk for tuppence, clean straw for nothing’.

In the pair of prints Beer Street and Gin Lane, Hogarth contrasts the happy inhabitants of a neighborhood where the tipple is good old-fashioned beer, with the alcohol-crazed denizens of a gin-ridden slum:

Today, Gin Lane is still used to describe a particularly squalid and dangerous slum.

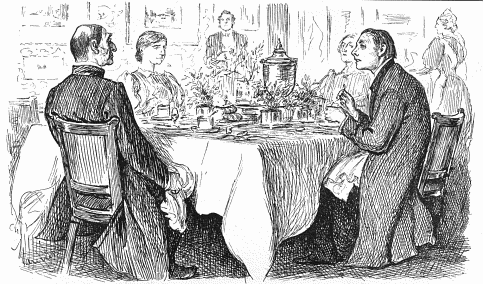

“All the same it is a curate’s egg of a book. While the whole may be somewhat stale and addled, it would be unfair not to acknowledge the merits of some of its parts.”

—Oxford Magazine (1962)

True Humility

Bishop: “I’m afraid you’ve got a bad egg, Mr Jones.” Curate: “Oh, no, my Lord, I assure you that parts of it are excellent!”

A curate’s egg— the expression deriving from the above 1895 Punch cartoon by George Du Maurier (1834-1896) — is what Americans call a “mixed bag”, something with good and bad aspects. The idiom is much beloved of film and book critics.

Du Maurier contributed to the language outside of cartoons. His smash hit novel and stage play, Trilby, gave us the trilby hat and the eponym for a person of hypnotic charisma, a Svengali.

“This bloody job is driving me off my nut–”

“Well, if you knows of a better ‘ole, go to it!”

Bruce Bairnsfeather (1888– 1959) was a soldier and cartoonist; he was something of a British, World War One equivalent to America’s Bill Mauldin. And just as Mauldin showed the common soldier in his Willy and Joe characters, so too did Bairnsfeather with his grumpy Tommy veteran ‘Old Bill’.

Bill’s words in the caption to the above cartoon have since been adopted as a humourous reproof to whiners.

Because many police constables used to have droopy moustaches like Bill’s, a popular nickname for the police is the Old Bill.

“The Home Guard is (…)an astonishing phenomenon, a sort of People’s Army officered by Blimps.” —George Orwell (1941)

David Low (1891-1963) created, for the Evening Standard in the 1930’s, the pompous, jingoistic reactionary Colonel Blimp.

The type was striking enough that to this day, arch-conservative, militaristic Britons are derided as ‘blimps’ for their ‘blimpish’ views.

“When I suggested firing the old staff, you could have heard a pin drop. I felt like ‘the Man Who’.”

H.M.Bateman (1887-1963) was a comic genius, best remembered today for his ‘The Man Who…‘ series of cartoons, in which the protagonist placidly commits a faux pas to the horror or hilarity of the surrounding crowd:

The Man who ordered a double scotch in the Royal Pump Room at Bath

By extension, anyone who ‘puts his foot in it’ in public is likened to ‘the Man Who (whatever the transgression)’.

“You should see the jury-rigged Heath Robinson contraption he set up to distill beer– couldn’t make head nor tail of it”.

W. Heath Robinson (1872–1944) was renowned for the crazy gadgets he designed, much as Rube Goldberg was in the U.S.A:

Any odd and complicated device is apt to be dubbed a ‘Heath Robinson contraption’.

During WW II, one of the automatic analysis machines built for Bletchley Park to assist in the decryption of German message traffic was named “Heath Robinson” in his honour.

“The Etonian Mr Cameron cannot avoid being Lord Snooty. The trick is to prove that he is the right one.” — Charles Moore, in The Daily Telegraph.

Lord Marmaduke of Bunkerton, a.k.a. Lord Snooty, was the star of a long-running strip in the children’s comic The Beano. He was a lord who happened to pal around with working-class kids.

Note his clothes– the school uniform of Eton, the traditional school for the elite.

Anyone suspected of overweening snobbery, or of belonging to the upper class, risks being called Lord Snooty— as has happened to current British Prime Minister David Cameron.

‘The Dan Dare sleekness of the new building makes a jarring contrast to its Victorian neighbours.’

Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future, was the hero of a luxuriantly illustrated science-fiction comic created in 1950 by Frank Hampson (1918– 1985).

The name Dan Dare is now a byword for futuristic design, often tinged with sarcasm.

“Cheer up, Fred Basset, it may never happen!”

When I first heard the above, my Yank mind was mystified…until I came across the eponymous strip:

Fred’s a basset hound, and like all dogs of his breed often has a mournful air. ‘Fred Basset’ is a jovial reproach to anyone pulling a long, sad face.

“A trillion-pound deficit? The mind boggles.”

Although the idiom “mind-boggling” already existed, the quirky variation “the mind boggles” was a catch-phrase from the charming Daily Mirror strip The Perishers, created by Maurice Dodd (1922- 2005).

Another usage from the strip, “go-faster stripes”, refers to racing stripes painted on a toy wagon. It has become a way of describing any useless or frivolous addition to a product.

Politicians are, of course, the traditional target of the cartoonist; if unlucky, they can be dogged by a nickname bestowed in ridicule.

Such was the case for Prime Minister Harold Macmillan (1894–1986), anointed Supermac by cartoonist Vicky (1913– 1966):

How to try to continue to stay top without actually having been there Note: Mac’s torso is, of course, padded

The press adopted the derisive sobriquet, which followed Macmillan all his life; however, with the years it took on an admiring sense.

Another Prime Minister, Edward Heath, was saddled for life with the nickname ‘Grocer Heath‘ by John Kent (1937-2003), deriving from the 1967 hit song ‘Grocer Jack’:

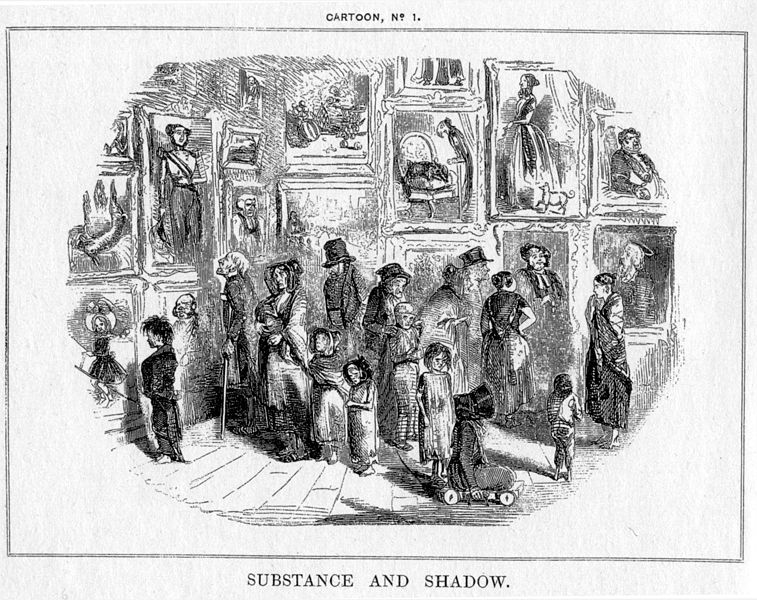

Originally, a cartoon was a painted or drawn preliminary study for a mural, mosaic, or tapestry, executed on stiff paper; the word comes from the Italian cartone, ‘big paper’, with the -oon suffix English often adopts when adapting a word from a Romance language ending in -on or -one (examples: from the French, dragoon, saloon; the Spanish: doubloon; the Portuguese: barracoon; the Italian: buffoon, pantaloon).

These cartoons were often beautiful works of art in their own right; witness the cartoons painted by Raphael , now in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, for the Sixtine Chapel’s tapestries. Below: The Miraculous draught of Fishes.

In 1843, an exhibit of cartoons for the tapestries of the newly-rebuilt Palace of Westminster (housing the Parliament) provoked John Leech (1817– 1864) to draw for the satirical magazine Punch a series of drawings called ‘Mr Punch’s Cartoons’. Here is the first one, titled “Substance and Shadow“, with the caption: “The poor ask for bread, and the philanthropy of the state accords– an exhibition.”

Thenceforth, cartoon designated a humourous or polemic illustration in the press.

The term coexisted for most of the 19th century with another, the comic cut.

Illustrators and cartoonists would draw on the cross-grain of a block of boxwood, which engravers would then cut into to make a printable woodblock engraving: hence, cut. (The practice died out in the early 1890s, with the advent of photolithographic printing.)

In 1890, publisher Alfred Harmsworth (1865- 1922) brought out a magazine consisting entirely of cartoons, called Comic Cuts (motto: ‘Amusing without being vulgar’.)

It was a roaring success, much imitated. It is therefore no surprise that comic cuts came to be a generic term for a child’s comic magazine; even though the original periodical folded in 1953, the term is still heard ( cf. Ralph Steadman‘s use of it in his 1990’s Comics Journal interview with Gary Groth.)

In the 1894 official Registry of Periodicals, for the first time listings for ‘comic magazines‘ were to be found.

Of course, most Britons speak of simply a comic or a comic paper.

The designation comic book is reserved for American periodicals. The first use of that term for a magazine of strip cartoons is found on the back cover of the 1897 collection, The Yellow Kid in McFadden’s Flats:

The word caricature is derived from the Italian caricatura ( from caricare, to load.). Although the practice of creating exaggerated, distorted images dates back thousands of years — see the comic masks of ancient Greek theatre — the caricature first really flourished in the Italian Renaissance. Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) was an early master of the genre:

The term entered English in the 18th century:

When Men’s faces are drawn with resemblance to some other Animals, the Italians call it, to be drawn in Caricatura.–Thomas Browne, Christian Morals, 1716.

And it was in the same 18th century that Britain produced masters of caricature unsurpassed today, such as James Gilray (1756 — 1815):

… or Thomas Rowlandson (1756- — 1827) :

Long may their heirs thrive.

Before we leave Britain, a recommendation for a pleasant London outing: visit the British Cartoon Museum:

…at 35 Little Russell Street, London WC1A, just a stone’s throw from the British Museum,

where you can lunch in the cafeteria within its stunning central court:

<

Then stroll to the marvellous store Gosh! Comics, 35 Great Russell Street, London WC1 B, one of the greatest comics shops in the world–if not the greatest.

Then take your latest comics purchases and laze away an hour or two reading them in Russell Square Gardens:

A top-hole summer afternoon is thus guaranteed the cartoon and art lover.

This concludes the series on comics, cartoons, and language; what have I learnt from my research?

First, although there are many contributions from comics and cartoons to colloquial English, their number pales beside those from other popular media, such as songs, plays, radio, films, television and advertising. This is understandable; cartoons are a far smaller slice of the pop pie.

Second, the far greatest number of contributions date from before 1930, tailing off until the present. This reflects, perhaps, the greater importance comics and cartoons had in public discourse… but perhaps also the lesser creativity today’s cartoonists display. The once verbally-lively funny pages are now a stagnant pool of bland, inoffensive dialogue.

It’s for the cartoonist of today to change that for the better.

This is part seven of a seven part series; part 1, part 2, part 3 looked at American newspaper comic strips; part 4 and part 5 treated comic books; and part 6 reviewed American panel gags and editorial cartoons; and there’s an index.

I would like to have a part 8, consisting of French, Italian, and other European colloquial languages enriched by their cartoons.

If you have any suggestions for cartoon-derived idioms along the above lines, please mention them in comments– or e-mail me at the yahoo dot com address alexbuchet

The British Cartoon Archive at the University of Kent is an indispensible treasure trove.

Toonhound is a very informative site on British cartoonists.

The British Cartoon Museum has plenty to show, as does

Punch, with a staggeringly massive gallery of cartoons.

The Political Cartoon Society hosts many images on its site.

The National Library of Australia concentrates here on cartonists from Down Under.

Yale’s Beinecke Library here has an informative exhibit with commentary on “British Comics at the Fin de Siècle”.

Great post!

I remember Fred Bassett from childhood. My local paper in NY ran it with Andy Capp (which I much preferred, though Fred was ok too).

Thanks, Tom. it’s interesting that only Britain (and its former colonies) developed a thriving syndicated strip market outside of the USA.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Strange Windows:Keeping Up with the Goonses (part 7) « The Hooded Utilitarian -- Topsy.com