I’d hoped to put this post later in the week and run more positive assessments first. But bumps occurred, and here we are. For Campbell fans, I’d urge you to read Suat’s preamble for a more loving assessment, or check out Robert Stanley Martin or Charles Hatfield for discussions of the Playwright. And of course the roundtable here runs all week.

__________________________

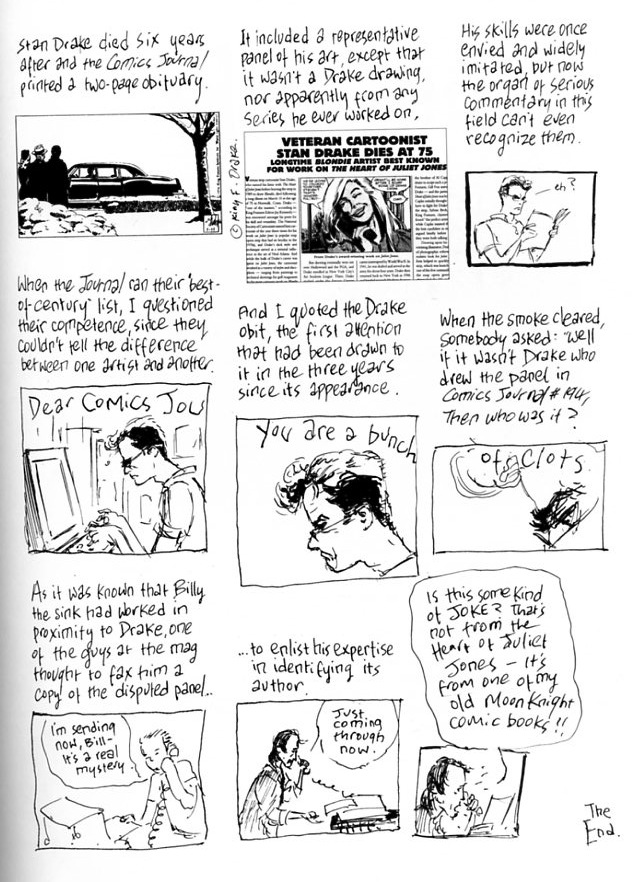

Eddie Campbell’s “How To Be An Artist” ends with Campbell writing an angry letter to the Comics Journal excoriating them for mistaking a Bill Sienkiewicz drawing for a Stan Drake drawing in the latter’s obituary.

As a former writer for the Comics Journal, I have to say that reading that page above filled me with something like despair at the milieu in which I’ve found myself. Not because the Comics Journal couldn’t tell Stan Drake from Bill Sienkiewicz; frankly, I like Sienkiewicz, know nothing about Stan Drake, and find the righteous rage for professionalized connoisseurship really uninteresting.

For many people this disqualifies me from having an opinion. Which is okay, because after reading that page, I don’t know that I want to have an opinion about comics ever again. Campbell’s one of the most lauded autobiographical graphic novelists of our day, “How To Be An Artist” is a well-respected work, and how does it end? With a tedious, penny-ante, in-group anecdote, hermetically spiraling into its own self-satisfied nerd knowledge. It’s like Campbell looked deep into the soul of the comics Internet and said, “here! juvenile comics knowledge score-settling — but it is art! Rejoice!”

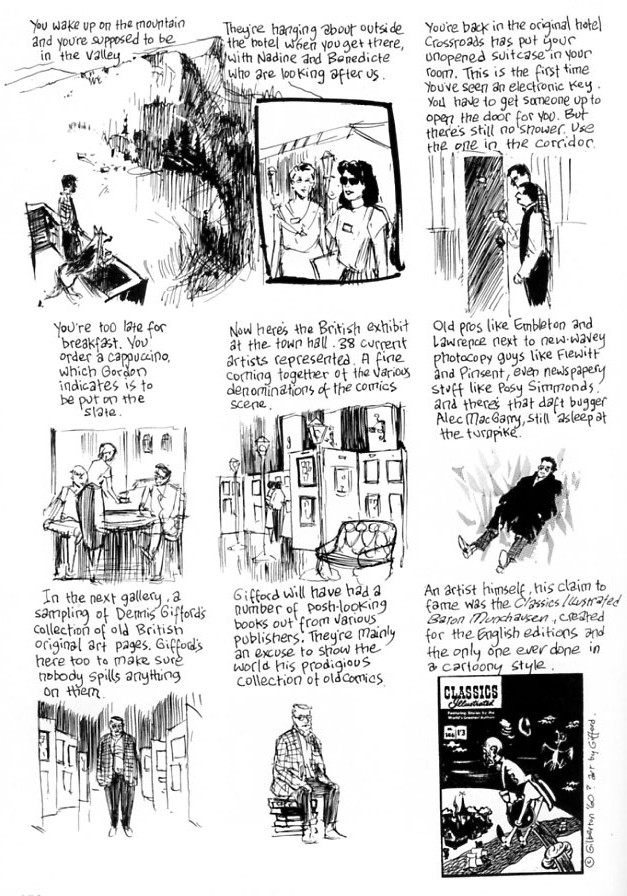

I wish I could say that this page was an aberration. But it isn’t. This is what much of “How to Be An Artist” is like; a brutal slog through endless name-dropping and industry gossip, an exercise in self-satisfied self-reference as Campbell casts a nostalgic glamour on himself for being in the room and on the room for having him.

Campbell does seem to have some sense that this is wretchedly boring and inconsequential. Or at least he does his best to tart it up, writing the entire book in the second person future tense, as if in hopes that grammatical shenanigans can turn bland and familiar careerist pseudo-revelations into a universal lyric.

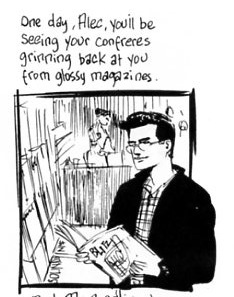

I guess you could argue that that image is supposed to be self-aware and self-mocking; Campbell puncturing his own ambitions. The thing is though…denigrating your own success isn’t exactly not boasting, just as turning down a Nobel Prize isn’t exactly an act of humility. Campbell’s deflations suggest pretty strongly there’s something to be deflated. Whether he’s undermining them or not, he’s talking and talking and talking about his own career path as if that career path is intrinsically interesting. And I would contend strongly that it is not.

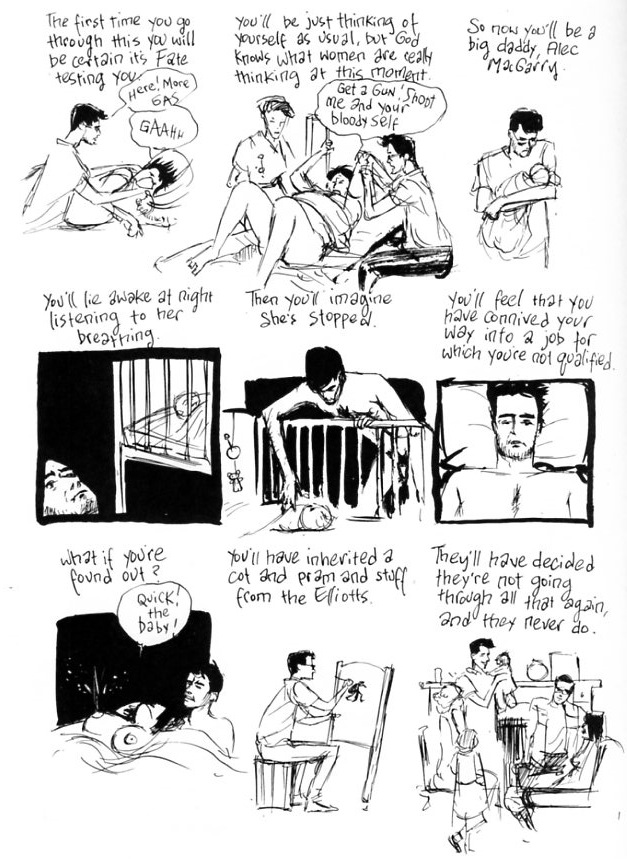

The universal elegaic also works particularly badly for the moments when Campbell switches from career to family.

I like the drawing here, especially in the first line; Campbell’s scratchy sketches, barely struggling out of the white space, seem almost to suggest that they were drawn during the birth — the sketch of his daughter’s little head points to the emergence of the little head itself. Life and art come together in the act of creation.

The problem is…the analogizing of art and birth seems too patly insistent. The second person narration castigates Alec for thinking only of himself…but self-flagellation is about the self too, and even moreso. Tellingly, we see the baby first in the arms of Alec, not of his wife, as if the sketch is more important than the person.

All of which might be okay if we didn’t immediately descend into the worst kind of sensitive new-age dad, parenting-magazine-ready clichés: listening to the child breathing, worrying that you’re not really a parent and you’ll be found out…the banality. It burns.

But the banality is the point, I think. As Campbell says, the page is not about his wife or child, but about himself…and specifically, it’s about validating his creation of the image of the baby by deploying his wife’s creation of the actual baby. The clichéd SNAG tropes are referents; they demonstrate that this is a serious artistic endeavor, linking Campbell’s comic to the familiar cultural sussurant mutter of emotional depth. I think it’s significant that the question, “what if you’re found out?” comes just before an illustration of Campbell drawing a picture on his child’s crib. The juxtaposition crystalizes the anxieties, both spoken and un-. In response to the worry that he’s not cut out for the child care (for which his wife, with her spurting breasts, is more naturally equipped), Alec moves to his own process of creation; his art is a sign of his competence as a father. But by the same token, the fatherhood — the mundanity of feeling all the things everybody else has told you that sensitive fathers feel — is the sign of competence as an artist. Comics are art because they’re about the real stuff that real art is about.

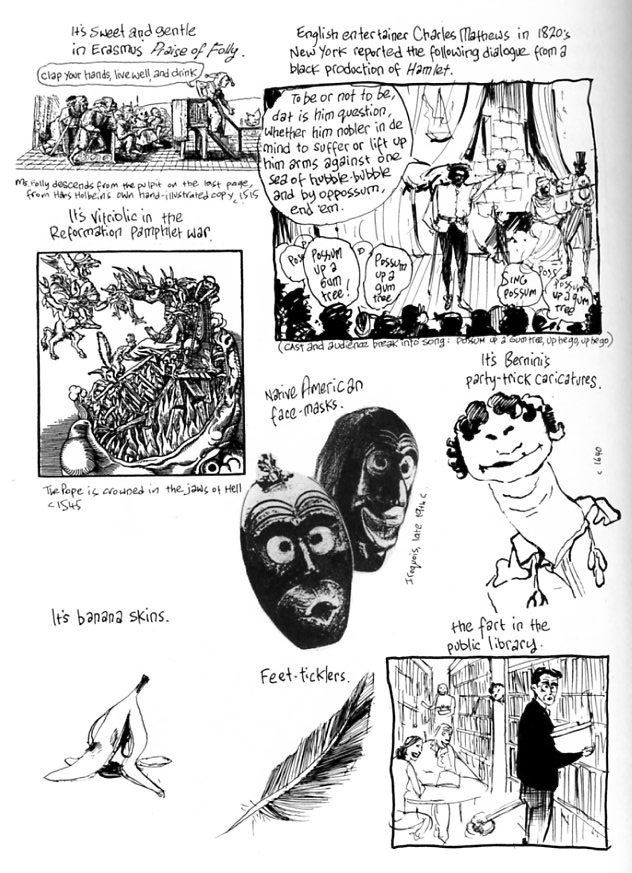

Campbell also makes the case for comics as art (or at least, for his work as art) more directly. For example, he reproduces many panels from his heroes and predecessors, situating himself in a history and tradition. He also spends some ink musing on the arbitrariness of artistic reputation — an arbitrariness which has obvious implications for the oft-but-perhaps-not-forever-denigrated medium in which he works. Perhaps the most enjoyable part of the discussion is his brief history of humor. “The true history of humour may never be written,” he says. “It defies that kind of organisation.” So instead of organization, he supplies an impressionistic view — a marginal history of marginalia, culminating in a one panel fart gag.

All of this is relatively engaging; kind of like a brief version of “Understanding Comics” who actually understands comics. Campbell’s insights never really rise above smart-guy-bullshitting-at-the-bar — but he is a smart guy, and his bullshit is often entertaining, if not revelatory.

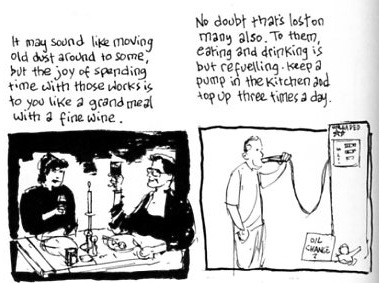

Still, as with the career and family, so with the arts commentary — beneath the quick economy of the sketches and the confident declamations (“No, the fine things speak across physical and temporal distances. A song, a tale, a cartoon, a chair,”) there lurks a ponderous anxiety and an anxious ponderousness. Whether it’s positioning himself as a connoisseur and belittling those who aren’t:

or imagining Alan Moore as the wolf of art among the philistine lambs or comparing his wait for career success to the trials of Odysseus, it all reeks of a strained, half-disavowed-but-always-reclaimed pomposity. If you’ve really got such a firm grasp on the torch of culture, surely you don’t need to keep beating us about the head with it?

In comments on this blog a little while back, critic Bert Stabler argued that:

autobio comics and art photography try to imbue a popular medium with gravitas and end up only escaping their navel by referencing the rather non-magnificent history of the medium.

That seems a painfully apt one sentence takedown of “How to Be An Artist”. The story trods back and forth from navel to history of the medium to career where navel and history of the medium meet, trying to embody gravitas through the very laboriousness of the trod. The central question of How to Be an Artist does not so much recur as curdle. To be an artist, follow these steps: say what other people have said about the quotidian vicissitudes of everyday life; hang out with other artists; look at enough other art that you can sneer at those who aren’t in the club. Repeat, I guess, until comics shuffles off enough of its status panic that ritual mimetic self/medium-trumpeting is no longer necessary to keep the entire endeavor from imploding under its own aggressive irrelevance. In other words, forever.

___________________________

I wrote this after I’d finished the “How to Be an Artist” section of Alec, figuring it was best to quit before everybody became further irritated. I subsequently did read the rest of the book…and while I think I could probably find something to say about the way that fetishization of working class heroes slides inevitably into suburban sit-com, I don’t really have the heart for it. Eddie Campbell has appeared a few times in comments on this blog, and has always been extremely gracious. I wish I liked his book more. I look forward to hearing other folks in the roundtable tell me why I should.

Yeah, I figured this is where we’d end up once I heard you were taking on Eddie Campbell’s Pants.

(Yes, I’m leaving the end of the sentence like that.)

I’m sure there’s going to be a heck of a back and forth on this one, which I’ll try to make the time to wade into, because I can’t think of any comics I like more than Eddie Campbell’s Alec stuff.

I am a little bothered that you zeroed in on the part of the book that is explicitly about comics, and while I don’t wish to malign your intentions, I can’t help but notice that it fits most comfortably into your practiced rhetoric on your pointed disinterest in comics qua comics. “How to Be an Artist” is one of five books collected in the omnibus volume, and yes, it deals directly with the author becoming a successful comics artist and is also a history of the brief “graphic novel movement” that he was a part of in the ’80s. It seems that since Campbell’s task at hand is the recording of his own life, it wouldn’t really do to not address his personal history of comics, and I don’t see it at all being out of proportion to the other material that makes up the vast majority of the book (youth, travels, family, etc.)

I also happen to think that all that stuff is pretty entertaining to read about, and also fits into Campbell’s larger, growing theme of himself as a solipsistic, short-tempered fool slowly acquiescing to the absurdity of life and growing more gently accustomed to it.

There’s quite a lot going on in that Comics Journal page you cite — there’s the heart-sinking neglect that a publication seeing fit to run an obituary of an artist doesn’t actually know enough to run the right art with the obit; there’s the inevitability of all artists eventually sliding out of view, some faster than others, but none of it lasts; there’s Campbell the author realizing that inevitability but Alec the character (and a representation of Campbell in the moment) being too much of the short-tempered fool who is too solipsistically close to the subject matter to see that it’s absurd to get as fired and angry as he gets; there’s a duality in that Campbell doubtless still feels upset (as I do) that better care isn’t taken with the memory of artists who we personally find important, and while we may recognize that it may only be nostalgia that motivates us it’s sad nonetheless; there’s also the neat tying together of the previously mentioned “history of the graphic novel movement” with the inevitable transience of art that’s achieved by ending on Billy the Sink.

Your reading feels woefully rushed and fit to your pre-ground axe rather than a result of a careful or critical look at “How to be an Artist” either on its own or as part of “The Years Have Pants,” an even more expansive and multifaceted work that the roundtable is nominally supposed to be about, yes?

Oh, my, I wrote an awful lot more than I really intended to. Just went back and added some semi-arbitrary paragraph breaks to make it more readable and less like the rant of a complete frothing nut on the internet. I’m sure you can find plenty to argue back against in that.

Looking forward to the rest of the roundtable…and I’ll come back and play some more when I’m able to carve the time out to read what I’m sure will be about ten dozen comments that get written before now and the next time I get a chance to look at the site.

Hey Jason. Damn it, I wish I’d known you were such a fan. Would have gotten you to write something. Maybe still possible?

I wrote about this one because it was the one that really pushed my buttons. If there’s been something else I really liked I would have written about that too or instead…but there wasn’t. Most of the rest I just found boring or garden-variety mediocre. If I have to write about something I don’t like, I’d rather it be something that makes me mad rather than just tired.

So, yeah, it’s because I’ve an ax and this fit it. Like I said, I wish it didn’t, or that there were something else that piqued my interest more fully.

“It seems that since Campbell’s task at hand is the recording of his own life, it wouldn’t really do to not address his personal history of comics,”

This is a cop out, I think. You don’t have to write about anything you don’t want to; your task as an artist is whatever you make it. He doesn’t record every time he goes to the bathroom.

I think it would have been possible for him to write about his art or his life in a way that interested me…or that didn’t seem like preening. The second person future tense is just absolutely egregious in this regard. It’s a horrible choice.

I like your reading of the last page; it’s generous and thoughtful. I kind of wish I could get that out of it. I just don’t, though. The sadness about the lost art just seems so wrapped up in demonstrating comics’ worthiness; the final ironies reversal so wrapped up in triumphant nerd knowledge…. It just depresses me. The hint of Campbell the creator looking down and knowing it’s all futile and kind of ruefully nodding over it actually makes it worse for me in some ways. It makes it literary…like all those novels where the guys come to terms with their youth through super-hero metaphors. If you’re going to deploy bitter nerd-knowledge, I’d rather you just deployed it; if you’re going to be that guy, be that guy. Partly because I don’t think you stop being that guy by looking down on him in wisdom.

Anyway…thanks for your thoughts as always.

Admit it, Noah, you wrote this just to pick a fight with me.

First, last, and always, “How To Be an Artist” is about the anxieties of career. And there’s no way Campbell could tackle that subject in an autobiographical context without engaging in name-dropping—the names he drops, almost without exception, are his peers and professional associates! Is name-dropping such a heinous aesthetic sin that if an artistic project essentially demands that you do it, you shouldn’t pursue the project?

Beyond that, Campbell’s references to others in the comics field go far beyond simple name-dropping. As I note in my review of The Years Have Pants in the forthcoming TCJ #301, his discussions of others in the comics field are invariably metaphors for his worries about himself. The closing section about Stan Drake’s obituary is extraordinarily poignant in this regard. The notion that an ambitious artist sees his or her work as a bid for immortality is a storied one—it dates back at least to Dante, and Dante attributes it to one of his mentors—and Campbell clearly shows himself to be in its grip. The panel you deride of Campbell imagining “seeing [his] confreres grinning back at [him] from glossy magazines” is an illustration of this attitude. What the screw-up with the Drake obituary highlights is how tenuous that grasp on immortality can be. Drake was a successful artist, a fairly notable one within the comics field, and someone whose work Campbell admires. Yet in his first moment of life and glory beyond death—his obituary—he’s effectively mistaken for someone else. So much for immortality, you know? So much for the whole point of an artistic career. It’s a darkly ironic and anticlimactic ending for the overall story, and the irony is only heightened by that someone else turning out to be Sienkiewicz, who is portrayed quite negatively throughout the piece, and is the closest thing it has to a villain. He is, in the context of his and Campbell’s relationships with Alan Moore, Campbell’s prodigal brother and opposite number—the flashy bad boy to Campbell’s more modest good one. Moore gave them both a ship to voyage to immortality with—and Billy the Sink (Campbell’s nickname for him) sank his.

This view of the Moore collaboration on From Hell as a voyage to glory—which it certainly was—is also what’s behind the analogy Campbell draws between himself and Odysseus, which is also a metaphor for anxiety, in particular the anxiety over whether From Hell would ever see completion. Campbell had several insecurities with regard to that: the Billy the Sink Big Numbers debacle certainly didn’t help with his view of his own abilities, and the threat of the rug being pulled out from under him wasn’t a boon, either. Two of the project’s publishers went toes-up before it was finished, and the third collapsed shortly thereafter. The fear of being (figurative speaking) lost at sea before claiming his crown and throne is quite justified by the events. And if you feel the Odysseus analogy is pompous, well, I think the pomposity is justified, too, as both a commentary on Campbell’s ambitions and in terms of From Hell’s stature in the field.

As for the Campbell’s treatment of becoming a father, that also ties in with the anxieties over career—the vignettes from Campbell’s personal life take “How To Be an Artist” from the anxieties of career to the anxieties of being an adult. It’s all of a piece thematically with the larger story.

As for your complaint about his embracing his pretensions and belittling those who don’t share them, it’s the flip side of his mocking those pretensions that you say you enjoy. He’s highlighting his contradictions, and the juxtaposition makes both views more vivid and effective.

And, and, and… well, let’s give you an opportunity to respond.

I rather enjoyed this essay. You found the history of comics bits more engaging than me, I think. It’ll be interesting to see what others have to say.

I have some thoughts about the 2nd person, which I’ll talk about Thursday. Mostly, I found the whole work very stock/cliche/old metaphor drawn out. Comparing art to childbirth and parenting is so tired.

There’s a great interview with Sienkiewicz in this month’s ImagineFX, by the way. You might enjoy it.

I think VM is the only one who is going to have my back on this one. It’s kind of fun to have the battle lines reshuffled.

Robert, I have to say, I really didn’t want to be fighting with anyone. I fully expected to enjoy the book. Everybody likes it! Why shouldn’t I? And yet here we are….

I think we actually agree that it’s about anxieties, which is interesting because I thought that’s where I’d be taken to task.

Name-dropping…maybe it works better if you really care about the names being dropped? That’s kind of my point about the insideryness of it. I’m not really interested in these ins and outs in themselves; I don’t read industry news or politics at all, ever, and that’s because I don’t care. I could be interested if anyone was actually a person…but it feels like name-dropping because it all passes in a sort of distant rush. He’s trying to make it an epic journey, or a mock epic journey, and yeah, I feel like treating your career path as an epic is just really hard for me to not take as boasting. And as I said, undercutting the boasting doesn’t make it not boasting.

It might help to point out that I loathe the Beats.

The page with the birth of his child is really a low point for me. It’s just so something I’ve seen 100 times before, his wife and child reduced to these tropes in his own career drama…even more so by his whining about how he’s reduced them to tropes in his career drama. I just have no patience for it and no interest in it.

Sorry…I mean, I’ve actually enjoyed Suat’s post and your and Jason’s defense infinitely more than I enjoyed the book. It’s obvious that it really resonates with lots of people I respect. But I kind of hate it.

Well, I lived the period he chronicles as a reader. I believe Suat did as well. I gather your attentions were elsewhere at the time, so maybe that has something to do with the disconnect.

But that doesn’t explain why I find the “Graffiti Kitchen” section as strong as I do. And it doesn’t really strike me as a Beat-style piece, so I’m a little hard-pressed to understand your antipathy for it.

I don’t know that I had a great antipathy to Graffiti Kitchen. Like I said, a lot of the stuff just left me indifferent.

It just sort of blurred together into a bunch of sexual trysts or who is he sleeping with or want to sleep with or whatever. It’s just so solipsistic to me; maybe that’s why I feel like there’s a connection to the Beats. I feel like he’s the only character who’s given a personality or interiority…I feel like that throughout the book. And his interiority isn’t especially involving; it’s young guy partying and shooting the shit early on and then suburban dad later on; I know those stories already.

I like the drawing well enough, and he’s got a nice sense of language. The stories he tells with those tools are just not anything I have any interest in reading, is the problem.

Reading the reviews of the playwright suggests I”d have a similar reaction to that. I would almost rather gouge my eyes out than read that comic after reading what you and Charles had to say about it.

I have big issues with the story on that one. I just downplayed it in the review because I was so impressed by Campbell’s realization of it. Believe me, I’ve had more than more than enough of portrait-of-a-sexually-uptight-nerd stories.

Yeah; I think that came through. And I like the look of the art there too; Charles’ explication of it is really nice. But I don’t think I can hack the story.

Noah: You will absolutely hate The Playwright. No question about it. It’s just chock full of your pet peeves, not to mention mediocre.

You already know that I find your objections to Alec perfectly valid.

On the other hand, you’re not totally opposed to name dropping: you thoroughly enjoyed Goodbye to All That remember? I don’t consider most of “How to be an Artist” to be a classic case of name dropping like that memoir. Campbell was a much more prominent figure than most of the people he cites by that time. Those were his colleagues, most of whom were unknowns or “giants” who never got adequate recognition (e.g. Don Lawrence).

I did want there to be more parts in the entire Alec saga which were closer to the section where he quotes Edward Lear though.

I read Goodbye to All That when I was, like 18! I really have no idea what I would think of it now.

fourteen months is a long time

Badum bump.

If only if only. I’m 39, alas.

Noah,

First let me just be super clear, because I was writing fast and sloppy earlier (though I’m not in a position to do much better now) that it was truly not my intention to suggest that you actually zeroed in on How to Be an Artist BECAUSE it fit into your established axe-grinding wheelhouse (what an astonishing accoutrement to the critical farm!) but rather I was disappointed that what you zeroed in on did hew so close to previous arguments you’ve made because I’d be much more interested in you engaging the other portions of the book. I could have guessed your reaction to the comics history in How to Be an Artist, and though I find the material absolutely fascinating and entertaining, there’s no accounting for taste and it’s no surprise to me that you didn’t.

That said, you seemed to be objecting to the very existence of the discussion of the world/industry of comics, and hence my statement about it being such a large part of Campbell’s life that, once he set himself to the task of recording his life on paper, it could hardly be avoided. How well he pulls it off is another matter — I think well, you think not. But the fact of its existence I think should and could not be a knock against the book as a whole.

I think a great deal of our disagreement on the early Campbell work can probably be found in your dislike of the Beats — not that I’m particularly a fan of the Beats per se, but I think that what I react to in Campbell is what a lot of people react to in the Beats — that perfectly chosen snatch of overly romantic memory, the way of reconstructing a perfectly ordinary life into an epic romance by sheer force of artistic will.

In terms of the later content — and actually, After the Snooter is my favorite of Campbell’s books — well, the Beats don’t enter into it all that much. I think part of what I like about the later books so much is experiencing Campbell’s artistic strategies mellow and wizen with age. His early stuff is Trying So Hard, and I really love it for that, I love how much he strains to find the piercing romantic moment. But his later work is so much more mature, so much more accepting of life’s absurdities and so much more aware of his own absurdities. Related to something you said in the Spiegelman comments section, that making oneself a flawed character engenders audience sympathy — I think that the early Campbell, of the King Canute crowd, does just this, and I think that the later Campbell recognizes it for what silliness it is, and also suspects he’s being just as silly himself in ways he can’t yet perceive. Thus the panel in which Current Campbell punches Young Campbell in the back of the head while Old Future Campbell urges him to reconsider his rash actions. That panel kills me.

Anyway, I’m sorry you didn’t end up enjoying the book. Going to go pass out into bed now…

“The story trods back and forth from…”

You mean ‘treads’.

The thing is, an artist doesn’t have to focus on their art when they’re reviewing their life. They can focus on whatever they want.

The most famous example I can think of is Aeschylus, who despite creating some of the most innovative artistic works in the world, had ‘fought at Marathon’ on his epitaph and nothing about his art.

When Campbell focuses on his own art in his autobio, it’s a choice, not an inevitability. I think we do his work a disservice critically by assuming it was some kind of externally driven necessity.

Yeah; I definitely agree with that.

I would say, too, that I’m not against artists writing about their art. I love the way Trollope discusses his art in his autoboiography, for example. It’s not not boasting exactly either, but it’s a really charming up-front boasting, where he basically talks about how proud he is of his work ethic (x numbers of pages a day; finish one novel before you get to the page count, start another) and how much money he makes from each book. It’s so thoroughly unromantic; I can’t help but be charmed. (Causing Domingos’ head to explode, if I remember correctly his opinion of Trollope.)

Ariel Schrag too talks about her art and her career with some frequency. It’s virtually always within the context of her relationships with others though; it’s never a hero’s journey. Instead it’s nervousness about how friends and lovers will take it, obsessive hopes and anxieties…it’s just not puffed up in the same way, or presented as if other characters are ciphers in her drama, though it often (especially in her last books) is integrated into narratives or intertwined thematically. (And this will definitely cause Suat’s head to explode…)

What about Fellini’s 8 1/2 (filming about his filming) or the many ‘studio of the artist’ paintings? It’s practically a tradition. So why shouldn’t a cartoonist cartoon about cartooning?

Yes, of course it’s a choice to discuss his art at all. He COULD focus his strips entirely on family, or he COULD focus his strips entirely on the growth of hair on one knuckle, or on the shapes of clouds that he sees every morning. But the initial choice of creation, at the beginning of the project (aka when he began drawing the King Canute Crowd) was to mine his daily diary for material to create short comics stories, many of them, adding up to a documenting of his life in barely disguised fiction (and of course, the disguise famously doesn’t last — as of After the Snooter, the character is no longer Alec but Eddie, which is appropriate as After the Snooter is very much about Campbell maturity defeating the old Garooga romance and replacing it with a different kind of organizing principle, one encapsulated in the anecdote about the Ignatz brick at the airport).

Anyway, post-digression: the project’s shape is well established by the time How to Be an Artist rolls around. I don’t find it at all surprising or really worth criticizing that Campbell chooses to discuss his life as an artist and in the comics industry. Criticizing HOW he does it makes sense to me — Noah thinks it’s preening, I think it’s a lot more complex and interesting than that. But criticizing the bare fact of its existence seems strange.

I also disagree wholesale with Noah’s summation of the book — I don’t think “How to Be an Artist” is ever actually a central question, but rather sort of a joke in that Campbell is narrating in the second person future tense events that fell together as a combination of unique effort and chance, and could in no way be seen as a prescription for success (aside from Campbell’s work ethic and dedication, I suppose), and I also disagree that Campbell’s goal in discussing the “graphic novel movement” is achieving gravitas. But these are all reasonable discussions to have, whereas criticizing the fact of Campbell’s discussion of comics seems…well, I mean, I guess you can do it, but I don’t really see the benefit.

I think he says it’s not a prescription for success, but more an explanation of a way of being. And it’s clear it’s meant as a joke as well. I don’t think that predicates against trying to achieve gravitas…again, undercutting kind of begs the question of why you think there’s anything to be undercut to begin with….

I find the puncturing of youthful romance as a theme really not something I want to read about either at this point, unfortunately….

I think it’s less of a puncturing than a mutating, because older Campbell is not without his romance, but it’s of a decidedly more perverse and bemused sort. But, y’know, if the theme don’t blow yer dress up, so it goes…

And I don’t think that it’s quite as binary as “reaching for gravitas” or “undercutting all importance”. I think Campbell sees the graphic novel movement as an important moment (as do I) but also, with his other eye, sees that its place in the larger world, that to most people it’s at best a footnote to their interests. Campbell’s achievement is not building something up in order to undercut it, but holding both thoughts to be true at the same time, a complex understanding of the relationship of important personal moments to the possibility or impossibility of actual “importance” in life. This is related to the bit about Schobert in Fate of the Artist, which I would guess you haven’t read as it isn’t collected in The Years Have Pants, and so I might be strung up for bringing it into the discussion, except Robert already talked about the Playwright which doesn’t even feature Campbell as a character, and so there.

No, no! Bring other texts in! Fear not!

It should be noted for posterity:

The original ending of “How to Be an Artist,” rather than the recently-added Stan Drake anecdote, was Campbell’s (or Alec’s) younger self, as a child with a sketchpad, looking up at the unseen narrator (hence all of the second-person future tense) and saying, essentially, “Bugger all that, I just wanted to know what pen to use.”

Hey Noah, have you tried clicking on the images? (to make the panels load bigger?) Its causing the images to load up sideways. Some sort of technical glitch at work.

Patchworkearth; that’s interesting. I might well have liked that better.

Pallas. Crap!. I know what happened, but fixing it is going to be a pain. I’ll work on it this evening.

Okay, Pallas, it’s fixed.

I haven’t read every comment here, so forgive me if this issue has been raised already.

“All of which might be okay if we didn’t immediately descend into the worst kind of sensitive new-age dad, parenting-magazine-ready clichés: listening to the child breathing, worrying that you’re not really a parent and you’ll be found out…the banality. It burns.”

—The problem is, Noah, all of that stuff is true. I’m sure you experienced something like it, and I know I did. Isn’t there something to be said for art reminding us of these perennial experiences? And that he would contextualize the birth of his first child within a story about becoming a professional artist, by rendering it in those terms seems pretty okay to me.

I agree it might be boring if one is after novelty, but doesn’t truthfulness trump novelty sometimes— in a work of non-fiction to boot?

—It is more interesting to people who’ve read the work of those he mentions. How many film-insider books do the same? Or memoirs from the world of literature? Maybe you should read the works he mentions.

—He does mythologize everything, of course. He’s done so in every work of his that I can think of. The self-mythologizing in How To Be an Artist is supposed to be somewhat ironic, or at least undercut by various admissions.

Bart Stabler’s comment is just too easy. The vast majority of autobio in comics has been presented in pretty casual ( as in not going for respectability) terms*. I honestly can’t think of many autobio comics but the one in question that reference Comics-History in explicit terms. Joe Matt has cartooned about his Gasoline Alley collections, but does that really count?

If you mean that within the text of the comic —the cartooning— you can see elements of those that came before, well, what comic doesn’t do that?

*Harvey Pekar was pretty clearly going for a kind of literary respectability

I don’t think I actually experienced my son’s infancy in that way, I have to say — as self-mythologizing of my own depth, or as a parallel between my wife’s having the child and my own creativity. I don’t remember lying down to listen to him breathing either. He spent most of the first months there screaming; he was pretty colicky. When he slept I wasn’t lyrically listening to him doing so; I was unconscious. There are obviously feelings of “holy shit, I’m not ready for this” — but I really remember those as being conversations with my wife. “Holy shit *we’re* not ready for this,” whereas Campbell juxtaposes his wife’s biological fitness with his own sense of inadequacy. I think that’s a pretty significant difference.

Having Campbell put his experiences in the second person to tell me I did in fact experience things the way he did was pretty annoying, honestly.

You should read Jason and Robert’s comments though; they both mount nice defenses of the book (as do you.)

Bert’s name is Bert, by the by.

I don’t see such a direct parallel between his fitness as an artist and his wife’s biological fitness. Maybe I’m misreading it.

I don’t think he’s presenting an abnormal amount of depth, either. The kind of self-mythologizing that goes on throughout the whole book ( and a bunch of his others) seems like it’s used ironically pretty often. I don’t think that occurrence is given more or less significance in the myth-narrative than much else, though it reads as significant in that basic shared-experience kind of way —the chaotic and dirty stuff of his *real* life that makes his mythic sense of inner-self seem pretty silly and incompetent.

I think that kind of romantic deal — the young, passionate artist on a quest for immortality— is pretty well represented by that myth. It works because throughout we’re reminded that it’s all folly. I sort of suspect that you don’t really respect that sort of young artist guy. I think your vision of creativity is much more academic ( or based in a kind of free-form curiosity) . That’s fine, of course, but I think the key to understanding fandom ( which is the story of American comics, really) is in understanding that kind of irrational passion, like Campbell’s for Stan Drake.

It’s hard to read comics without that in mind, is what I’m getting at. You can hope that comics will move beyond that— that it’ll become more like film or something— but comics wouldn’t be made today without that element.

Hey Uland. That’s an interesting point. As you say, that’s actually something about comics that I dislike. In a lot of ways, you’re confirming what I say in the essay, except for you most of what I see as negatives are positives.

It’s helped me understand better where you’re coming from, though, and maybe where Campbell is coming from too. So thanks.

I don’t follow your reasoning about the obituary thing. I haven’t read the book, but doesn’t he say on the page you reproduce that it was three years after the obituary appeared he used it as an example of something else. And he doesn’t even say he’s such a big fan of Drake anyway. Isn’t it more about respect, getting the facts in the obituary right. My dad edits a small town paper and he says if any of his monkeys screwed up an obituary of a notable citizen by not bothering to check the facts, he’d sack them on the spot. My dad Stan Drake still appearing in the daily newspapers at the time he died. Wasn’t he the artist on Blondie?It wasn’t like he was some old forgotten person. Couldn’t they just have cut the strip out of that day’s paper?

“Having Campbell put his experiences in the second person to tell me I did in fact experience things the way he did”

Noah, the second person “you” is not you the reader. Believe it or not Campbell is not insisting that you will grow up to marry his wife.

It’s “How to Be an Artist.” A particular artist: Eddie Campbell. “How to Be Eddie Campbell.”

It’s a prophecy, or series of instructions, to himself.

“Believe it or not Campbell is not insisting that you will grow up to marry his wife.”

That’s a good one, Leigh!

He’s turning his experiences into a universal. The you is to himself, but it also suggests that it’s more than himself; that it’s a lyrical universal.

He doesn’t expect me to marry his wife. He expects me to feel like his description of his marriage to his wife describes my experience as well. It doesn’t. I resent the implication.

My wife hates this book too, incidentally. More than me I think.

“He expects me to feel like his description of his marriage to his wife describes my experience as well. It doesn’t. I resent the implication.”

I don’t think he does expect that. I think Campbell suspects you’ll find SOME parallels, but just as important are the divergences, because he is describing the very specific circumstances of his life. Since those circumstances arise largely out of idiosyncratic choice and complete chance, there’s an ironic effect achieved by narrating it in the second person future tense — the narration is phrased as if this is the inevitable means by which the universal you will become an artist, but it’s so obviously (a) not inevitable and (b) not universal, that it’s supposed to be funny.

“My wife hates this book too, incidentally. More than me I think”

she hates the book even more than she hates you? that’s bad. get out of there!

You need to come with your own rimshot.

Jason, I can see that for some aspects. The fatherhood thing and his reactions to it are really cliched though. It’s not specific enough to undercut the second person. It emphasizes it instead. It’s just standard-issue lyrical parenthood piffle.