![]()

Dominique Goblet depicts her father as a late medieval Madonna, nurturing his child, right hand in blessing. Drawn on disparate, pasted-together pieces of paper accompanied by shakily calligraphed Gothic handwriting, it is simultaneously a mockery and an illumination.

The image is from Goblet’s Faire semblant c’est mentir (‘To Pretend Is to Lie,’ 2007), a work that the author spent more than a decade creating. In it, she recounts episodes in her life to explicate, or at least represent, truthfully parts of its relational structure and emotional involvement. In this scene, Dominique visits her estranged father for the first time in five years. He is a drunken retired fireman and divorcé, now living with a rickety woman, Cécile—prone to hysteria bordering on the paranoid and drawn like Munch’s Screamer—a precarious stack-up of damaged goods. Dominique brings along her young daughter, Nikita, whom she leaves reluctantly in the hands of Cécile to walk the obliviously chipper dog.

The conversation turns serious, and the father starts blaming the daughter and her mother for the family’s misfortune. The icon mock-up marks a crescendo of his self-righteous diatribe: “And when she left, who took care of you? Wasn’t it me, perhaps? Didn’t you have your little packed lunch every day for school?” It is largely a comic image, but crafted as a question rather than a condemnation, because how can she deny the factual accuracy of that statement?

A collage of clips, rips and palimpsests, rendered in nervous, uneven line, the image emphasizes its limitations and shortcomings. While certainly pathetic, the father crucially is basically sympathetic; his soft facial features and mismatched almond eyes reveal an inner vitality, if also a lack of awareness. The child, in contrast, appears shrewd and present. This is her interpretation, ironic and reverent.

On several occasions in the book Goblet risks hyperbole in this way, employing dramatic juxtapositions and symbolic imagery to accentuate expression and enrich observation. It’s a risky strategy, but one she clearly feels is merited by the material, mundane as it might seem. The book is an attempt to engage a set of issues less by narrative and more by perspective. Goblet finds truth in reiteration, approaching her relationships from different angles and extending the focus beyond herself to the people around her, attempting to make sense of their experience: her father, her mother, and her boyfriend, Guy Marc Hinant, who co-wrote two of the chapters. She interweaves fact and fiction to expose the experiential, emotional truths behind the pretense of autobiography, attempting as well as she can to sidestep solipsism and mythologizing—the ophthalmic migraines and temporary blindness she suffers at a point of severe stress unassumingly accrue metafictional connotations.

Her portrait of her father is essentially a loving one. Despite their estrangement, she cracks convulsively when she learns from a friend of the family—after everyone else—that he was hospitalized days ago and is apparently dead. He isn’t, and he ends up comforting her in the hospital waiting room instead of the other way round. She is suffering from crippling anxiety that her budding relationship with Guy Marc is failing before it has even fully started, and given the juxtaposition, it is hard not to interpret this in the light of her familial disjunction.

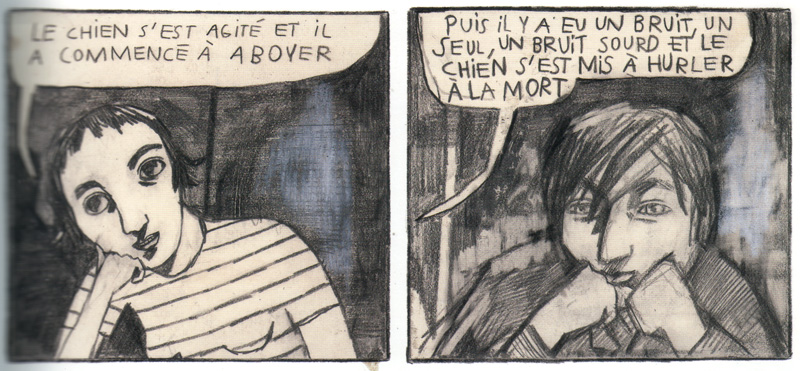

As we’ve seen concurrently, Guy Marc has left his previous relationship unsolved. He wavers and relapses, wearing thin Dominique’s need to trust. Goblet draws the specter of his ex haunting them as they go about their daily business, lending a sense of sad menace to her portrayal of the beginnings of a relationship. She captures attentively the ambulatory conversations by which we get to know each other and the sense of promise they hold. In this case—perhaps a little too appropriately—it starts with a ghost story told in exacting, captivating detail, and continues with a no less carefully delineated recipe for pasta with tuna. And situations like Dominique tucking in Nikita in the graffiti-covered room of Guy Marc’s teenaged son (he’s with his mother) have an acute sense of reality to it. The book breathes lived experience.

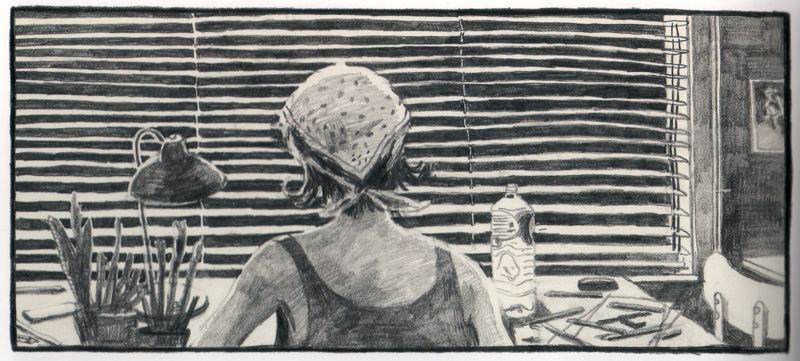

Though basically expressive, relying on externalizing emotion and broadening character to great effect, Goblet’s painterly pencil-and-chalk drawing at times captures more subtly revelatory moments of insight. This is especially true of the chapters involving her relationship with Guy Marc, in which her endeavor to step outside herself is most fully realized. The distracted, slightly troubled gaze with which he looks at her as she is telling him the ghost story beautifully illustrates the sense of displacement from the present tense that unaddressed problems may visit upon us, yet also suggests his dawning infatuation with the remarkable new person in front of him. And later Goblet depicts herself at her drawing table, against the light of the blinds, as seen from Guy Marc’s point of view, his desire and affection for her almost palpably immanent. An extraordinary instance of empathetic projection through drawing.

Goblet generally excels at displacing emotion, by metaphor as seen in the symbolic portrayal of her father, but also, and perhaps more notably, through transposition. Some of her most intense instances of emotional disclosure about both her father and her boyfriend are expressed not in this book, but in Souvenir d’une journée parfaite (‘Recollection of a Perfect Day,’ 2001), which she wrote and drew while work on Faire semblant was ongoing. Her father eventually did die, and Souvenir is in part a way for Goblet to express her feelings and reflect upon his significance to her shortly after it happened.

Instead of addressing her relationship with him directly, as she does in Faire semblant, however, she uses the conceit of looking for his gravestone at a mausoleum in the cemetery of the Brussels suburb of Uccle. Scanning the many names, she happens upon one of them, Mathias Kahn, and creates a fiction of this anonymous person’s life, which she interweaves with places, instances, and emotions from her own—“fiction as an extension of autobiography,” as she calls it in the brief afterword. The book concentrates primarily on thus charting her relationship with her father, but the “perfect day” she imagines for Kahn also contains a particularly moving, indirect declaration of love that simultaneously becomes redemptive of the old fireman’s flawed life and indicative of hers with Guy Marc.

Souvenir is a compelling work even when read without full cognizance of this metalepsis, but it is still a rather distancing conceit with which to engage personal matters. One understands why Goblet moved on to the more risky, and ultimately more difficult, direct form of representation in Faire semblant. Yet, as the title indicates and as the symbology already discussed should make clear, displacement is also central to this book.

The most emotionally fraught scene describes a traumatic instance of abuse inflicted upon the young Dominique by her mother, against which her father failed to intervene. Characteristically, Goblet seeks not to condemn but understand, describing the exasperating childish antics of her young self mostly from the point of view of the mother, making the latter’s momentary loss of control all the more understandable. Only when their full ramifications become apparent do we switch unequivocally to the child herself in a shocking full-page exclamation.

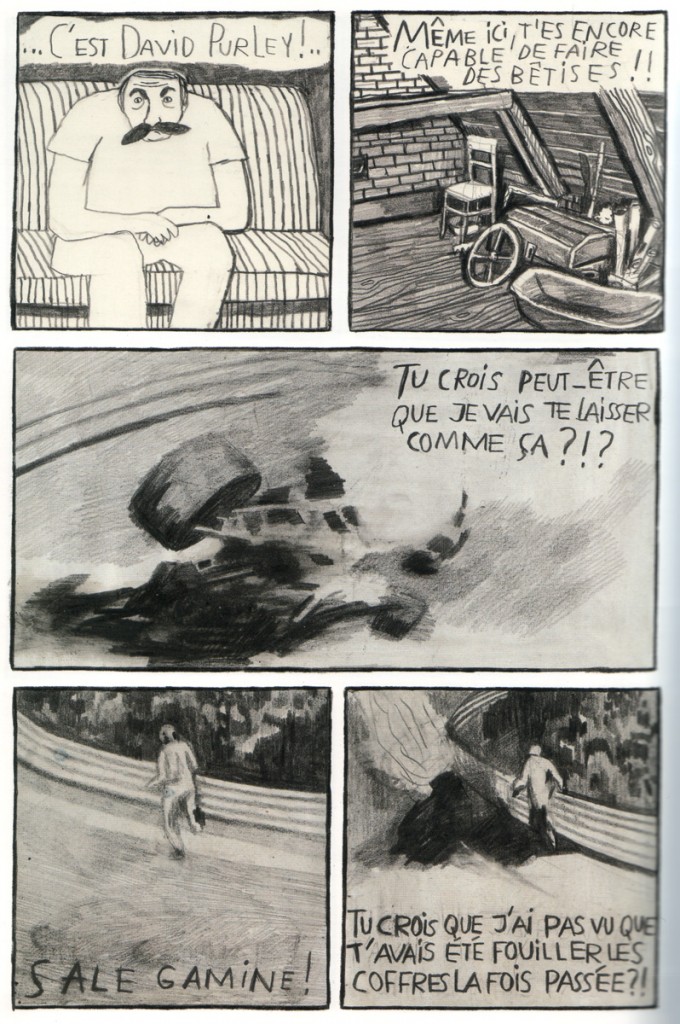

Concurrently with, and extenuatingly of this, we’ve been watching the father watching Formula 1 on TV, drinking beer. It’s the fateful 1973 Dutch Grand Prix, in which the gifted young English driver Roger Williamson perished in a violent crash. This juxtaposition is a fiction, devised by Goblet symbolically to represent her father’s crucial moment of neglect—a moment of which he had no recollection, as we learn from the conversation between Dominique and himself in the book’s diegetic present.

The heartbreaking spectacle of watching Williamson’s colleague David Purley attempt to extract him from the flames, drawn from video stills, becomes a potent placeholder for the author’s inability to address exhaustively this key episode of her childhood. Unfortunately she almost (but only almost) ruins it by ironically having the inebriated father loudly proclaim how he—the professional fireman—would have been able to save Williamson’s life had he been present, oblivious to the familial conflagration that mother and child are still reeling from. It is a didactic explication of an otherwise perfectly pitched, powerfully moving sequence of empathetic exegesis.

But then, Goblet’s strategy of pretense in the service of truth is a fraught one, and whether the individuals implicated—especially the father and the relatively vaguely defined mother—would recognize fully the events as depicted is of course questionable. But it is a noble, involved, and beautifully realized attempt at illuminating the vagaries and ultimately inexplicable realities of the relationships that shape and define our lives.

Dominique Goblet’s website. Souvenir d’une journée parfaite at her publisher FRMK’s site. Domingos Isabelinho on her and her daughter Nikita’s latest book Chronographie here at HU.

“One understands why Goblet moved on to the more risky, and ultimately more difficult, direct form of representation in Faire semblant.”

I was curious about this…do you think that autobiography is innately more risky than fiction? And if so, in what way, or why?

I guess that the argument is that it’s more personally painful, or more fraught or charged…. I just wonder if that’s always the case, and/or if there aren’t considerations that sometimes balance that out. I think autobiography can often be easier to market, for example. And in terms of aesthetic ambition, your description makes it sound like Recollection of a Perfect Day is more original/weirder than the later work…which could be seen as riskier in some sense….

No, that statement specifically has to do with Goblet’s work as I see it. I don’t think autobiography is harder or more risky than fiction, and you’re certainly right that the former has become a crutch for many aspiring cartoonists.

What I meant to say is that “Souvenir”, though in some ways the more successful and even original work of the two, is ultimately also safer than “Faire semblant.” The issues and emotions Goblet hints at, and at times sublimely evokes, in “Souvenir” are engaged more directly and profoundly in “Faire semblant.”

Ah, that makes sense.

Pingback: Links: blandede bolcher