What are the ten comics works you consider your favorites, the best, or the most significant?

That’s the initial question Robert Stanley Martin presented for voters in our best comics poll. Voters could vote for the best comics, their favorite comics, or the most significant comics. Which made me wonder, what’s the difference?

From the poll answers, it’s clear that many people do see a definite difference between “favorite” and “best”. For instance, in commenting on his list, cartoonist Larry Feign noted that “Some comics I would consider “great,” but not my favorites, such as Peanuts. I have confined my list to my favorites and greatest influences.” Even more emphatically Melinda Beasi in comments said that “I will say for the record that I would have refused to participate if I’d been required to come up with a list of “best” comics. I only caved because Noah insisted they could just be favorites.”

A simple distinction between “favorite” and “best” would be, perhaps, subjective/objective. “Favorite” is what I like myself, for personal or idiosyncratic reasons. “Best” is what is objectively superior, by some sort of universally applicable criteria. So one could say, for example, “I don’t really like Crumb’s work very much personally, but I recognize that he is such an objectively great illustrator that he deserves a spot in the top 100 comics.” Or you could say, Dokebi Bride may be one of my favorite comics ever, but of course it isn’t the kind of work of genius that deserves a place in the top 100 comics.” Crumb is not a favorite, but perhaps a best; Dokebi Bride is not a best, but a favorite.

Obviously, these distinctions are useful and meaningful, or people wouldn’t use them with such frequency. Still, I think they have some limitations.

First, it’s worth pointing out that no one is actually in a position to determine whether a comic is “best”, because no one has read every comic ever created. No doubt there’s at least a few people out there who have read every comic on the list of 115 best. But is there anyone who has read every comic on every list submitted by all 211 participants? For that matter, there are whole traditions of comics that aren’t even hinted at on our 115 best comics list, most likely because none of the people who submitted a list are familiar with them. There’s a massive comics scene in Mexico; I believe there is a significant comics tradition in India; there is a comics tradition in China. Do we know for certain that nothing created in those places is better than Watchmen or Peanuts or Little Nemo? Or, for that matter, how do we know that some obscure mini-comic distributed to 12 people and seen by no one else isn’t the best comic ever? Even the most cosmopolitan and knowledgeable comics reader is going to have seen only a tiny fraction of all the comics ever created in the world, which means any “best” is only “the best that I’ve seen” — or, in other words, a favorite.

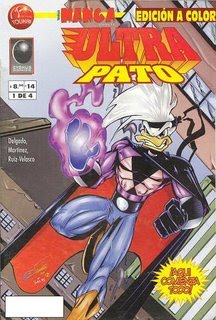

Ultrapato by Edgar Delgado. It could be one of the best comics of all time for all I know.

On the other hand…I wonder if it’s possible to see something as a favorite entirely divorced from objective, or at least communal, ideas about quality. “What I like” isn’t an arbitrary effusion of my individual romantic selfness; it’s a variegated hodgepodge of standards picked up from others, many of which (a dislike of clichés, for example, or an antipathy to slick advertising art) don’t even make sense outside of a social milieu. Even what one chooses to read tends to be influenced by ideas about “best” — I doubt I ever would have looked at Little Nemo if so many people (whether acquaintances or, through his comics, Chris Ware) hadn’t told me that I should. “Favorites” exist, not in isolation, but in social spaces where personal likes are disseminated and codified, where they bleed into collective determinations of quality. Would I be such a fan of Peanuts if one of my closest friends was not also a Schulz devotee?

In some ways, the best/favorite split mirrors the general human problem of objectivity/subjectivity or culture/self. Eric Berlatsky (that’s my brother!) got at some of these issues in a recent comment.

There’s a fairly large gap between “objectivity” and “subjectivity”–and there are alternatives to both approaches. That is, even if there is no concrete unassailable criteria for judging art, this does not automatically mean that you’re left with “different strokes for different folks”. Criteria for judging individual works tend to be defined by groups…or “the social”… not by the work itself or the individual onlooker. So, Jeet knows what “kinds” of things are appreciated by the social (or a particular interpretive community, a la Stanley Fish). So…even if he doesn’t particularly like something as an individual, he can say “it is good.”—This is based on a kind of broad social agreement (or a less broad agreement within an interpretive community) about “what kinds of things are good.” Thus, Jeet can disagree with himself (“I don’t really like it, but I know it’s good, anyway). None of this has much to do with objectivity…but it doesn’t have much to do with “what kind of art is good is purely subjective.” Even the belief that artistic judgments are subjective comes from the social (and the notion that there are objective criteria for judging art is probably social as well).

I’d agree with that…and maybe elaborate that the issue isn’t just that subjective/objective is simplistic, but rather that there’s not really any place from which one can determine whether it’s simplistic or not. The self is embedded in language and, indeed, in images. How can you separate you from the world that makes you? Or (more trivially) how can you tell whether Watchmen is your favorite because it’s the best, or the best because it’s a favorite? Are you shaping the list, or is the list shaping you?

This is why I think Robert was right to ask for best, or favorites, or most significant. Not because all of those are acceptable, but because it’s unclear that they are even systematically distinguishable. The appeal of best-of lists, I think, is not that they embody either absolute standards or individual enthusiasms, but rather that they tie both together into a single frustrating, fascinating knot.

I’d differentiate between favorite and significant (as in historically significant/influential), more than favorite/best. You can to a certain extent say what has been historically significant/influential to comics as a whole. I tried to make my list a bit of a compromise between the two, picking some that are both favorite/significant (Peanuts, Krazy Kat) and just favorite (How To Be Everywhere, Par Les Sillons). Had I just done significant I think it would have been a considerably different list (I would have had to include Tintin). Of course the ones I did pick that I think are both favorite and significant were the ones that made the end list… so maybe it’s a moot point.

Significant is a little fuzzy too, though, since you get into the question of significant to what…. Tintin is obviously hugely popular and very influential on many creators, but if you’re Domingos (I hope he doesn’t mind me mentioning him here!) it’s outside the genealogy of comics that are artistically meaningful. There are different communities in which you can talk about influence, I guess is the point, and choosing between them puts you back into considerations of best or favorite.

Yeah, I did a “best” list which was mostly recent hardcover collections/reprints of great works, in order to give a real idea of the scale of said great works. However, it is sad to nail 10 because a list of truly essential stuff should be maybe 20 or 30 or more. Then I said hell with it and sent instead a “rocked my world” list of single issues that had a major impact on me at one time or another, maybe not the “best” but definitely personal favorites.

“Best” sucks anyway, what is this, a county fair?

Dyspeptic ouroboros?

I disagree with a list of favorites for this poll. Here’s why (first of all I couldn’t agree more with Eric): that said:

I separate two judgment spheres, the individual and the collective. The former is the sphere of the favorites, the latter the sphere of the best/more significant. We can discuss the latter, but we can’t discuss the former. Since this blog is a public sphere all favorites become automatically “best/significant” (and I know that, in comics, best and significant is not the same thing, but passons). Hence: something that shouldn’t/can’t be discussed gets out there for public scrutiny (that’s one of the problems of our day and age: the two spheres are easily confused). But this is a status problem… On the other hand Noah, you’re perfectly right: all best comics are, in the end, favorites. That’s why I think that we should discuss criteria first, not individual artists as if we’re all judging by the same criteria. We do that once in a while when we discuss comics’ exceptionalism.

I’m very interested in what peoples’ favorite comics are, and NOT AT ALL interested in what they think the “objectively best” comics are. The latter reeks of undue self-importance, where someone is trying to appeal to vast audience and historical considerations, as if to say, “I’ve tried to give everyone a nod, and I think I’ve pretty much nailed it.” Comics fans don’t need den mothers who are going out of their way to try to appeal to everyone. No adult does. This is the same reason I’m bored with so much anime/manga/comics/movies blogging consisting of people reviewing titles that they’re not really interested or invested in. This dispassionate approach is a great way to make sure a steady stream of content is published on your site, but I’d argue it has little to no value.

Very much enjoying the idiosyncratic and very personal lists.

Oh, I definitely consider Tintin highly significant (without it there would be no clear line – not that Hergé invented the clear line, but he definitely helped to spread it). That’s where I separate “best” from “significant.” Since fannish criteria have been so flawed over the years we can’t think as if we were studying painting, for instance…

I chose a mix of things for my list, and I’m pretty sure I fretted at poor Robert, who likely heard the same thing 215 times.

I chose Junjo Romantica, which I was certain would not get any other votes, because it is both favorite and significant for being a favorite despite what many would consider huge flaws (the art is idiosyncratic in the extreme; it’s kind of like the Rod Stewart of manga. That guy’s singing is ridiculously scratchy/awful, but also SO GOOD. Well, not now, but back then, OK?).

I was certain some items on my list would not get any other votes, but dammit they’re awesome (Only the Ring Finger Knows). Uh. I also do feel they’re significant, but obscure. *sigh*

Rod Stewart’s early work is thoroughly awesome, and also very critically validated (there’s a book of 100 best albums by I think Jimmy Gutterman where Every Picture Tells a Story is number 1.)

I think “best” and “most historically significant” are, to one degree or another, tropes for “favorite,” anyway. Criteria of aesthetic value and/or historical importance are largely developed to validate personal preferences. Mind you, I’m not knocking them; I think both go a long way towards developing and exercising critical thinking skills. I just don’t believe there’s any Platonic ideal for art.

The range of material in these lists is just amazing. I enjoy seeing what people voted for a lot more than the consensus tally.

I agree with Domingos in principle that the conversation about criteria needs to come first (although I appreciate the list as fun and useful in a more idiosyncratic way.)

The problem I see is that conversations about criteria never really get very far, first because the elements of fandom that remain often cause critics to be too emotionally attached to things (including their own opinions), and secondly, I think, because comics only started giving a damn about aesthetic criteria after the rest of the arts started deconstructing their traditional aesthetic criteria. There’s a lot of emphasis on “history as criteria” — but it’s extremely materialist history (as you can see in Jeet’s comments about Krazy Kat), not the kind of “take historically significant works, analyze them formally, codify formal attributes of historically significant works into aesthetic criteria” process you saw in the other arts 75 years ago. You don’t get good formalism out of the historical crowd, like you did in the other arts before the postmodernists, and the less historically minded folks are allergic to consensus. It’s like comics got pre-deconstructed.

I don’t really agree, Robert, that historically, criteria of value were developed to validate individual preferences. I think that’s what happens now, but historically they were developed to validate the preferences of an elite class or of academics, but those preferences generally were considered and debated and political rather than primarily emotional and nostalgic. I suppose it’s an open question which is better!

I’m not sure I’d quite draw that line between political and emotional. Nostalgic subcultural preferences are very political…and I think they’re more considered and debated than you’re giving them credit for, though the terms of debate are maybe somewhat different than you’d like to see.

I’m also leery of crediting critics of other mediums with quite the systematic approach that you’re claiming. I mean, Pauline Kael is probably the best known film critic around, and she certainly falls much more into Robert’s description (i.e., using criteria to justify personal preferences) than into any kind of complicated historical/formal investigation. There’s certainly academic work which is more formally engaged (like Stanley Cavell)…but that’s academic work. There’s formally engaged comics academic work as well, but it’s usually these days not really about canon formation qua canon formation because the academy doesn’t do that anymore….

I was indulging my polemical side a bit when I said historically significant was a trope for preference, but I don’t think I’m entirely wrong, either. There are several examples of “historically important” work in the arts that most people–including scholars–don’t consider of much aesthetic interest. In comics, it’s not unusual to see the term bandied around by cultists for this or that work who are just trying to exalt their personal preferences.

Man, how much more boring would the list(s) have been if it had just been “best”? I know my list would have resembled the top ten, and so would plenty of others’, I’m sure, and then we’d have 50 things under it getting one vote each, and lots outraged comments that anybody could consider, say, X-Men to be the best anything.

Caro:

What you say certainly makes sense for bourgeois societies, but aristocrats never needed any criteria. They knew what was great because their education included the arts. They were surrounded by all the arts since they were very young (curiously enough they tended to fantasy and escapism pretty much like comics fans do; only the Bible prevented them from going even farther in that route, I guess). That’s why all criticism is pedantic and a bit snobbish: critics try to separate what’s good from what’s not that good using intelligence, but art appreciation is, in the end, the realm of the feeling (this paradox is what ultimately gives a bad rep to critics; that’s also why I think that it is very important to separate the private – what one feels – from the public – what one thinks – in these matters). The art critic is a product of the enlightenment and the art market. Since we’re heading more and more into an atomization of society and relativism the critics’ role became increasingly irrelevant. Enter the Internet, of course, in which everybody’s a critic in a Babel of voices…

Robert: no one mentioned any platonical ideals for art. What’s inevitable is that societies need (for various reasons, some of them very practical like the creation of syllabuses or the attribution of grants) to create a Kantian intersubjectivity. That’s what critics try to achieve, but it’s increasingly difficult to do so. i don’t follow the art market, but it seems to me that in there the political and the politically correct are the main criteria right now. It’s like in that Zapata film with Marlon Brando: the peasant fights the powerful to see himself in a powerful situation after beating him… All this is very Buzzellian :)

It doesn’t matter one bit if the choice is “favorite” or “best.” The moment the data entered the game it became “best.” It’s how it’s played…

Some of my favorites?

For starters:

Any comic book drawn by Wally Wood and inked by Steve Ditko, or any comic book drawn by Steve Ditko and inked by Wally Wood. Those two guys went together like peanut butter and jelly, in my opinion.

Almost any Silver Age pre-superhero Marvel Monster stories — especially the ones drawn by Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko.

Sad Sack

1960s-1980s fanzines/small press publications

Sugar and Spike

Steve Canyon — especially between 1947-1960

Anything by Orlando Busino

Anything by Bob Montana

Silver Age Marvel western comics

Any comics covers or non-sports trading cards painted by Norman Saunders

Anything by Russ Heath

Domingo’s comment about the aristocracy’s tastes being shaped by their immersion in the arts from birth is approaching the heart of this subjective/objective thing.

Art shaped by elitism is very different from art shaped by money. The subjectivity of the educated elite vs. the objectivity of cold hard cash. The former is nourished on our collective memory, the latter is terrified of it.

Odd, but in the end, capitalism looks just like marxism as far as the artist is considered. No memory, no class, no style, just the eternal hell of the mob.

Mahendra:

Yeah, that’s right… but it’s also true that in the Ancien Régime the arts were supposed to serve the happy few. The people could only have access to religious imagery and not exactly for aesthetic reasons.

Since you talked about Marxism and Capitalism isn’t it interesting that Film Studios in Russia stopped production after the fall of Communism? What I mean is: what’s worst?, State censorship or money censorship? I view Capitalism as worst than Fascism as far as culture is concerned. In the end we’re in aristocratic times again: only a happy few are well educated enough and have money enough to enjoy great art.

This may muddy the waters but…there’s a similar debate in metaethics about what makes moral judgements true. There, contemporary philosophers distinguish between two dimensions: (1) objective/subjective and (2) relative/non-relative.

(1) A proposition is subjective if its truth (or, possibly, its aptness) depends on one kind or another of our mental states–what we like, or think, or something similar. (e.g. “Noah likes ice cream”) Otherwise, it’s objective. (e.g. “Noah is a man”)

(2) A proposition is relative if its truth depends on the context of utterance. (e.g. “I’m a man”) Otherwise, it’s non-relative (e.g. “Jones, one of the Jones boys is a man”).

These dimensions are entirely orthogonal, so any combination is possible (although some are more plausible than others).

I think you can transfer these dimensions straight into (meta-)aesthetics, and they’re orthogonal there too. The impression I get from this thread is that most people here support a combination of (I) subjectivism — aesthetic judgements depend on our reactions/preferences/values etc. — and (II) relativism — these reactions/etc. can vary from one individual to another. Then, on top of this, they think that (III) reactions/preferences/values/etc. are to some extent shared between individuals, groups, subcultures etc.

It’s good that this is the consensus–because it’s the only remotely plausible view!

This detailed business of subjective & objective makes my head hurt, I have to confess.

But about the remark that we have re-entered the Age of Aristocracy, I would agree, except that this is a mostly anti-intellectual aristocracy … they make bad patrons and a worse audience.

capitalism vs. fascism vs. marxism … for artists & critics & intellectuals, capitalism at least allows us our lives. What we trade in is beneath money’s contempt.

I miss the Ancien Regime … at least they took the Enlightenment/les Lumieres seriously.

They should do that, it cut their heads off ;)

As for this new aristocracy being anti-intellectual… maybe, I’m not saying that it isn’t (the old one was anti-intellectual also), but they certainly have plenty of intellectuals working for them. I would argue that high art nowadays suffers from an excess not from a lack of intellectualism…

Capitalism pays what sells. In mass art, at least, what sells is the lower common denominator.

If I’d known it was “favorite” and not “best”, I might have submitted a list… :(

Something I tweeted a while ago to Noah is that ranking and canon-creation are activities that men get involved with a lot more than women. Part of the reason that popular female musicians fall out of the “music canon” is that women tend to not be on the front lines fighting for their inclusion. There’s something guyish about thinking that your personal preferences – even if they are informed/mediated by a set of publicly debated standards – should be universal.

This also explains the infantilization of mass art, of course…

…should be or can be universal.

” In mass art, at least, what sells is the lower common denominator.”

Domingos, this is where you and I disagree. Sometimes mass art is horrible, sometimes (Peanuts, the Beatles) it’s great. The things that make something popular and the things that make something good aren’t positively correlated, but they’re not negatively correlated either. They affect each other, but in unpredictable ways.

Of course, you don’t really like Peanuts or the Beatles (you can’t possibly like the Beatles. I will be very disappointed if you like the Beatles.)

Subdee, I hadn’t really thought of that. I wonder if it’s true? Hierarchies are certainly stereotypically male; I just wonder if that stereotype is true in this instance…. For women and the music canon, for example, it seems like there are maybe other reasons for an imbalance…

Of course I don’t like The Beatles.

But we don’t disagree that much. Some mass art (The Beatles is a good example) is at least acceptable as entertainment while some other… Anyway, that’s not Capitalism’s problem re. culture. The problem is that if something doesn’t sell (and great art selling through mass art market circuits doesn’t) it isn’t done. Or it is done, but no one or very few pay for it. That’s the problem of comics. Lists like this one don’t help either, by the way…

Noah — Domingos and I went back and forth about this on the OLD old “Comics Journal” message board about five years ago. I agreed with your point of view.

Unfortunately, there is no accessible archive left of our discourse, so all I remember is Domingos and I strongly disagreed with each other.

Wait, I do remember pointing out to him that folks like Rembrandt cranked out portraits and other paid commissioned paintings, and that some of those paintings were seen by what was essentially “mass audiences” of that era. In short, the work of many classical artists meets most of the criteria used by art experts today to dismissively describe the work of contemporary popular culture artists such as Frank Frazetta.

In short, I feel that if the Louvre is still standing in 500 years, there is absolutely no reason why a Frazetta painting shouldn’t be displayed right next to a Raphael.

I think my argument made Domingos’ head explode, but I was being very sincere.

I said it, Mahendra said it and I repeat it: when money is the only value to measure everything true values can’t exist. Money is like a virus, it proliferates and destroys everything else.

Frazetta is kitsch, Rembrandt isn’t, case closed.

I think I have more to say about all this that this but two quick points: I didn’t really stop to count the decades but I was thinking much earlier than Kael and Cavell, Noah. Like Matthew Arnold or Walter Pater or Ruskin. And not aristocrats, but elite bourgeoisie, in terms of education, as Domingos said. I do think they and critics like them established the foundation for “great works” that we used in the humanities right up to their deconstruction in the ’70s and ’80s. I don’t know whether they were immersed in the arts from childhood as the aristocracy would have been, though. Many of them seemed to come from relatively-meagre-for-the-middle-class backgrounds and turned to academia to earn a living.

But I definitely didn’t mean to imply, Noah, that their evaluatory criteria were not political — they were very political — but not really all that “emotional” in the contemporary sense of fannish nostalgia. Perhaps it’s too fine a distinction to be useful…

Oh, sure; I’ve had this discussion with Domingos as well. I’m happy to agree to disagree with him though (especially since I like Rembrandt a lot more than Frazetta myself.)

I’m wondering Caro whether fandom is a recent phenomena? It can’ be entirely…there’s been something like popular culture around for a fairly long time….

Fandom as such I guess is recent but pop culture surely not. But I’d say the idea that pop culture opinions, fannish or whatever, should influence or play a role in critical consensus is quite new. Critical consensus was the purview of educated elites/experts. Academia wasn’t always as removed from public critique as it is now — even as late as the ’70s there was more of an academic flavor to public critique.

Comics is probably the least important of the places where that particular kind of populism causes problems.

Organized science fiction fandom dates back to 1929/30.

I remember that discussion, Noah. I even quoted Jesus Christ.

Caro:

Where are those places that are more important than comics?

Domingos wrote: “Frazetta is kitsch, Rembrandt isn’t, case closed.”

Some Frazetta, of course. All Frazetta, no.

If one defines kitsch as work thrown together to appeal to “the masses,” then Rembrandt did his share. This moses painting, for example:

http://www.rembrandtpainting.net/rmbrndt_1655-1669/1655-69_images/mose.jpg

I’ve always felt that any artist should only be judged by the best examples of his/her work, for the simple reason that the road to any masterpiece is strewn with countless previous failures.

Domingos, the place I was thinking of is located at the intersection of East Capitol Street, NE and 1st Street, NE, Washington, DC.

Caro:

The supreme court? (I googled) Can you elaborate, please? I’m all against populism in the arts, but I don’t see why it would be harmful in law. I’m not saying that it isn’t, I’m just saying that I don’t see it.

Russ:

That’s no definition of kitsch at all.

Ha, google is leading you slightly astray: it’s actually the US Capitol. The Supreme Court is very close, but more at the intersection of Capital and 2nd. http://tinyurl.com/4yvuzeb

The phenomenon is very similar to what’s fueling the Tea Party: Time-Tested Know-how from analysis of the Things We Like, the inability to see things from the other guy’s outside point of view, rejecting the considered analysis of experts in favor of “Main Street” common-sense and knee-jerk criteria that bolster strongly emotional beliefs. It’s pretty much traditional American Jacksonianism turned into a fandom where it’s no longer one way to look at things but the Right Way to look at things — a cult of Fox News and the ghost of Ronald Reagan.

A teacher of mine called it a “Cold Civil War” which I thought was very apt.

Putting the tea party’s roots in fandom is fun, but I think it’s more a very traditional American distrust of government. The American Revolution coalesced around radical propaganda too….

And I don’t remember you quoting Jesus Christ, Domingos! That makes me sad that I don’t remember; that sounds really entertaining….

Oh, I see, populism in politics is indeed dangerous. Thanks, Caro!

“I agree with Jesus Christ here: “it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.” It’s easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a work for hire, pop pap kitschy artist to do great art.”

Oh, the political and ideological roots are squarely Jacksonian, Noah, no doubt. There’s a really good recent essay in Foreign Affairs: http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/67455/walter-russell-mead/the-tea-party-and-american-foreign-policy

But the social dynamics are pure fandom. And the danger comes…well, a friend put it thusly: “Yeah, right. No extremist political force ever succeeded in intentionally destabilizing a country enough that they were swept into power to fix the chaos they caused in the first place.” There’s democratic populism, and then there’s the manipulation of the masses…

I’m still not especially convinced that the dynamics are fandom specifically rather than that of any clique or faction. What makes the tea party more like the comic book subculture than like European right-wing parties? Or like the pro-life movement?

I don’t know much about the European right wing, but a big difference from pro-life here is the power of celebrity personalities and their opinions, even when they’re contradictory – the American right wing is very shaped by and dependent on media, and their relationship to that media is pretty much that of a fan.

Well…first of all, I’m not sure I entirely buy the idea that the Tea Party is a creature of Fox News first and foremost. Second…I think there’s a pretty important difference between aesthetic commitments (which usually involve chatting with friends) and political commitments which actually involve organizing.

I think the right has many characteristics of a subculture, and fandom has characteristics of a subculture, but I don’t think that makes the right a fandom.

I don’t think it’s just Fox News — but it’s definitely media-attached. And it’s an extremely aestheticized movement. I think you’re overstating the difference between aesthetic and political commitments — it’s easy for you to see how political aesthetic committments are; is it really hard for you to see how aesthetic political ones are as well?

Not all aesthetic commitments fall into the “chatting with friends” category. Think about the pre-counterculture hats and gloves and what forks to use and how to cross your legs. Those are “aesthetic” committments — but they were also highly aestheticized political commitments, as are things like opposition to miscegenation and a preference for American cars. Anything that has a strong “them/us” component to it tends to be aestheticized in some powerful way.

But the relationship of the right to, say, Rush Limbaugh (to pick a widely known one) is much more like fandom than was, say, the relationship of ’70s punk to safety pins, even though both serve as markers of the “ingroup”.

No, I’m certain it is aesthetic in part. I’m just not at all convinced that the organizational pattern isn’t continuous with earlier rightwing movements. I mean, are you telling me that the tea party isn’t very much church based? It’s a subcultural identity based around a bunch of markers, some of which are aesthetic, but which are also, I think, very much religious, probably regional, and certainly demographic and racial. There can be a mix of those things in fandoms too — that’s why it all looks like subcultures — but in fandoms the aesthetic is a lot more important and the other things less.

The US has several centuries of right wing movements in its past. They’re always shaped by the media stars of the time, be they Father Coughlin or Pat Robertson or Rush Limbaugh. I just don’t see the Tea Party as all that different. Certainly, it’s more like earlier right movements than it is like comics fandom.

The objective best comic of all time is X-Force, vol. 1, # 22.

It’s science, look it up.

————————-

Domingos Isabelinho says:

…aristocrats never needed any criteria. They knew what was great because their education included the arts. They were surrounded by all the arts since they were very young…That’s why all criticism is pedantic and a bit snobbish: critics try to separate what’s good from what’s not that good using intelligence, but art appreciation is, in the end, the realm of the feeling (this paradox is what ultimately gives a bad rep to critics; that’s also why I think that it is very important to separate the private – what one feels – from the public – what one thinks – in these matters). The art critic is a product of the enlightenment and the art market. Since we’re heading more and more into an atomization of society and relativism the critics’ role became increasingly irrelevant. Enter the Internet, of course, in which everybody’s a critic in a Babel of voices…

————————-

Excellent!

————————

mahendra singh says:

Domingos’ comment about the aristocracy’s tastes being shaped by their immersion in the arts from birth is approaching the heart of this subjective/objective thing.

Art shaped by elitism is very different from art shaped by money. The subjectivity of the educated elite vs. the objectivity of cold hard cash…

————————–

I was pondering yesterday over the seeming paradox of the mega-rich William Randolph Hearst not only greatly appreciating “Krazy Kat,” beloved by the intelligentsia and hip folks of the time, but keeping the strip alive by insisting his newspapers carry it! But then remembered how he loaded San Simeon, his palatial estate, with carefully-picked art treasures from Europe:

—————————-

[Hearst] was an eclectic and obsessive collector of art, amassing collections that were said to be outstandingly good in 20 categories and the best in the world among private collectors in five categories: Silver, Armor, English Furniture, Gothic Tapestries, and Hispano-Moresque Pottery…

—————————–

http://www.darrenwestlund.com/CambriaTreasures/Hearst3.html

Now, can you imagine a Rupert Murdoch, or any other modern-day billionaire, being sensitive to, much less a cognoscenti of art and culture? Garish displays of wealth is what they’d go for…

—————————–

Domingos Isabelinho says:

…In the end we’re in aristocratic times again: only a happy few are well educated enough and have money enough to enjoy great art.

——————————-

My formal “education” was utterly mediocre; it was only finding an art magazine lying in an art class, with an article about Dali, that turned me on to the Surrealists, and thence to art in general. (Science had been my passion beforehand.)

And by “enjoy,” do you mean own? Very few can afford “great art,” but through books (either purchased or in libraries) one can appreciate the world’s art treasures; have complete collections of quality repros of Vermeer, or Goya…

——————————

mahendra singh says:

… about the remark that we have re-entered the Age of Aristocracy, I would agree, except that this is a mostly anti-intellectual aristocracy … they make bad patrons and a worse audience.

capitalism vs. fascism vs. marxism … for artists & critics & intellectuals, capitalism at least allows us our lives. What we trade in is beneath money’s contempt.

——————————-

Yes, yes…

——————————

Domingos Isabelinho says:

…As for this new aristocracy being anti-intellectual…they certainly have plenty of intellectuals working for them…

———————————-

My collage on that reality: http://i1123.photobucket.com/albums/l542/Mike_59_Hunter/HistoryOfCivilization.jpg

———————————

“It’s easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a work for hire, pop pap kitschy artist to do great art.”

———————————

Talk about loading the argument! Might as well say, “”It’s easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a pathological liar, kleptomanic to be honest.”

More instructive than the Frazetta vs. Rembrandt comparison (I wouldn’t go as far as to dismiss FF as “kitsch,” but his work is certainly far closer to that area; consider the Frazetta images conscripted for airbrushing onto the sides of vans and motorcycle gas tanks) was a recent “New Yorker” piece about a Frans Hals show, which perfectly encapsulated what I have found so unmoving about his work. From the online abstract:

———————————-

His celebrated brushwork excites at a glance. In “Boy With a Lute” (circa 1625), a lad calling for a refill recalls the louche youths of Caravaggio’s light-in-darkness style, but with a blithe speediness that is remote from the Italian’s frozen radiance…

The lingering mystery about Hals’s art is its lack of deepening development. The tone seems stuck at a lazy bonhomie, amusement for a rising, self-satisfied commercial class. Hals figures into history as a stylist, but also a contractor to the bourgeoisie. His dishearteningly pedestrian world hardly bears comparison to the enchanted realms whose Prosperos are Rembrandt and Vermeer. Beyond his predecessors, Hals was the first virtuoso of the visible brushstroke, but no other Old Master seems to have made art so little for his own fulfillment.

———————————–

http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/artworld/2011/08/08/110808craw_artworld_schjeldahl

The first virtuoso of the visible brushstroke was Titian.

the father, son & holy ghost of the brush: titian, velasquez & rubens.

At that technical level, subject matter is unimportant. And note, all three artists subtracted from their technique once they matured. That’s the paradox of technique, you gain it in order to (hopefully) reach the level of throwing it away.

Not the other way around.

Oh, poppycock. Just because you like Art Tatum doesn’t mean you have to hate the Ramones.

There’s no formula for good art. Sometimes technique is great; sometimes it produces slick boring crap. Sometimes punk is great; sometimes it produces amateurish boring crap. You have to take it case by case.

But why eat hamburger when you can eat steak? With a good Bordeaux?

Because the analogy isn’t a very good one? Tatum isn’t steak and the Ramones aren’t hamburger; they’re different artists who do different things, and each have their own pleasures.

the subj/obj thing will torment us and our descendants forever, thank god

you say tatum

I say potato

you say ramone

I say hey-ho-lets-go

time for my nightly sedative ;)

The problem, Noah, is that pleasure can’t be discussed. If you put it that way the discussion is kaput. Not that I’m interested in discussing the Ramones and Art Tatum in the first place, by the way…

No, lots of people discuss pleasure. Emotions aren’t any more subjective than language; that is, somewhat so, but not entirely. Our identities and our pleasures are created by society as much as the other way around.

I was wondering if jazz is too lowbrow. I presume Mingus counts as actual art though, yes?

Jazz hasn’t been lowbrow for decades (I find Art Tatum a bit on the side of the virtuosos and I don’t like virtuosos much)…

But, anyway, what you say above about pleasure is not the point: anything can give pleasure and nothing can give pleasure. I may feel pleasure listening to a piece of music today and feel absolutely bored by it the next day… The piece didn’t change, my mood did. If that happens to the same person imagine the infinite variations to millions of people. I suppose that (put here the blockbuster of the day) gives pleasure to millions. That’s not why I think that it is good or bad (bad most likely).

I suppose that I’m not an utilitarian, after all, hooded or otherwise :)

Well, sure. That’s why interactions with art are a dialogue, not a science experiment. Pleasure is part of that dialogue, as it is in conversation or interaction. Just because it’s not reproducible from person to person, or even with one person over time, doesn’t mean that subjective assessments are worthless…or even absolutely subjective.

Tatum’s definitely a vituoso…though he has soul too, I think. I find Oscar Peterson more technique without much else…though he can be enjoyable in the right company too.

Domingos wrote: “That’s no definition of kitsch at all.”

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary. “kitsch” is defined as: “something that appeals to popular or lowbrow taste and is often of poor quality”

That pretty much matches my paraphrased definition of “work thrown together to appeal to ‘the masses,'” doesn’t it?

Noah and Russ:

Strangely enough I can answer to both of you at the same time. If A gives me pleasure (if A appeals to me) and I say “A is kitsch and appeals to me,” I’m saying something about me (I’m attracted to kitsch), but it says absolutely nothing about A and about what kitsch is, does it?

Noah: kitsch is a great example of something of poor artistic quality which is highly pleasurable.

———————-

R. Maheras says:

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary. “kitsch” is defined as: “something that appeals to popular or lowbrow taste and is often of poor quality”…

———————–

But aside from that “often of poor quality” caveat (which indicates, sometimes it’s not), reproductions of Van Gogh and Rembrandt paintings are highly popular among the masses!

Sometimes a fine original, such as Dürer’s sensitive praying hands drawing ( http://www.turnbacktogod.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/Albrecht-Durers-Praying-Hands.jpg ), becomes “tackyfied”:

http://ny-image3.etsy.com/il_fullxfull.253397591.jpg ,

http://www.christmas-treasures.com/SpinShades/Catalog/Images/762.jpg ,

http://www.acrylic-world.com/images/dbprayinghands.jpg ,

http://images.craigslist.org/3n73k93m95V65O55Z3b7k7981bb5f12621051.jpg ,

http://2tim215.com/images/handsonbible1d.gif ,

http://www.furnituredecoreasy.com/images/jobar-praying-hands-fountain.jpg

(Eesh! The last looks like “Praying Hands Have Risen From The Grave”! Actually, it’s a fountain, where “The water changes its color every time it flows into the hands.”)

There’s outstanding art which can appeal to the masses, and other — “Waiting for Godot,” Pollock, Giacommetti — which it takes more sensitive/educated tastes to appreciate.

———————–

Domingos Isabelinho says:

Noah: kitsch is a great example of something of poor artistic quality which is highly pleasurable.

————————-

Pleasurable in the way that junk food is pleasurable; strong, unsubtle “flavors”; appealing to the masses, rather than the cognoscenti…

The examples of the “tackyfication” of the Dürer drawing (which he called, simply, “Hands”) are instructive. What was austere has glitz and gloss slathered on top, details — a Cross, rising Dove, Bible — added, for those to whom the Christian meaning wasn’t blatant enough, I guess…

(One for the “Old Masters Swipe File”: http://hektoeninternational.org/Durers_praying_hands.html )

Domingos — Your answer is really no answer at all.

In my opinion, at least two of Frazetta’s paintings are masterpieces: “Death Dealer,” and “Egyptian Queen.”

Both, while they are not at the same level as Rembrandt’s best work, are still brilliant examples of 20th Century art. Not 20th Century popular culture art or kitsch, but ALL 20th Century art.

I’ve never taken kitsch to be necessarily linked to the uncouth masses but rather to the intent of art exceeding its ability to realize that intent. Terrence Malick = kitsch. John Waters doesn’t = kitsch. Frazetta didn’t particularly aim high, but his art is what it is. Most modern pop music both aims low and isn’t able to even accomplish that.

“Most modern pop music both aims low and isn’t able to even accomplish that.”

And yet, it is exponentially superior to mainstream comics.

There are various definitions of kitsch. my favorite is Milan Kundera’s in _The Unbearable Lightness of Being_ (it’s also a great story with a Christ that ate, but didn’t take a dump, and Stalin’s son’s death. Kundera aimed at political and religious kitsch. A more technical approach is Umberto Eco’s: kitsch is the prefabrication of the effect. Kitsch is an exaggeration of the effect (it knows its aim): it may be grandiose and operatic (Terrence Malick, yes) or, exceedingly sentimental… Kundera’s definition is about the content (kitsch is whatever hides the crude realities of life: it’s a great propaganda tool), Eco’s is formalistic.

Talking about design and architecture: kitsch is whatever wants to seem what it is not.

What’s maddening in Frazetta’s case is his amazing technical skills. In spite of that he, as Charles put it, aimed very low. You may also want to check out the Frazetta discussion on this very blog.

This has nothing to do with Frazetta, but cute and saccharine are kitsch: Lynn Johnston.

But Domingos, you could use the very same argument you make against Frazetta against artists like Rembrandt.

How many paintings by Rembrandt were simply commissioned portraits of wealthy upper class or aristocrats? Considering HIS great painting skills, that sure wasn’t shooting very high.

I’m not sure why you have such a low opinion of Frazetta’s work, but I suspect it has more to do with the fact that Frazetta was active in your lifetime than anything else.

I suspect that if “Death Dealer” had been painted 500 years ago, your view of it might be very different.

There’s also Adorno’s definition, which I’m fairly fond of (and which I imagine is basically the source of Eco’s…). It’s in Aesthetic Theory, sort of emergent throughout the book (see link below), but the famous quote is from page 312:

He then goes on to talk, appropriately, about aesthetic vulgarity and the relationship of art to privilege. Good stuff.

http://books.google.com/books?id=NGxSnig-u3wC&printsec=frontcover&dq=adorno+aesthetic+theory#v=onepage&q=kitsch&f=false

This conversation is really solidifying my sense that kitsch is not an especially useful aesthetic category. Adorno seems to want to use it as a barometer of authenticity, which I think is generally a really unhelpful way to talk about art. Domingos seems to be arguing for exaggeration of effect…though where does that leave Bosch or John Ford or Hopkins? It seems like it’s really just a way to denigrate popular entertainment, in which case I’d rather somebody just say they hate popular entertainment (which Domingos, to be fair, generally does).

Kundera is a pompous, thumb-fingered fool for the most part. The Unbearable Lightness of Being is snooty eastern european intellectual kitsch if anything is.

Russ, the thing about Frazetta is that he’s really really pulp, in a way Rembrandt is not. “Pulp” here means his work is very consciously hyperbolic and trashy. Hyperbolic and trashy isn’t a bad thing; I like lots of hyperbolic, trashy art, and Frazetta does that really well (though not with the originality or verve of, say, early Van Halen…but still). But it’s pretty different from what Rembrandt’s doing, whatever the latter’s compromises with capitalism. You’re not getting where Domingos is coming from if you really think he wouldn’t dislike Frazetta whenever the man happened to be painting.

Russ:

You’re talking to Charles, not to me. I don’t dislike Frazetta’s Death Dealer that much, to tell you the truth… I find his sexual politics a lot more troublesome.

Caro:

Great quote, yes (I need to reread Adorno; my limitations with him are related to my visual focus; Adorno talks mainly about music). I understand Adorno, but I also understand Noah’s comments. Kitsch is always cold and detached (ex.: Pompier painters).

Noah:

I never read The Unbearable (and I did exit the film house when I committed the mistake of trying to watch the film version). I just read the kitsch chapter which is absolutely great. Try it, Noah.

John Ford has a kitschy side (_The Informer_ is unbearable; it’s his catholic upbringing) masterfully balanced by James Fonda’s underacting and John Wayne’s no bullshit posturing (this was a huge influence on Carl Barks’ Uncle Scrooge). The mixture of catholicism’s unrestrainment and protestantism’s restraint is quite marvelous. As for Bosch: do you think that he didn’t show the darker side of life? I mentioned two definitions of kitsch because I think that they must go together. As for my dislike of mass art (I never call it popular art), I think that John Ford is mass art, no?

PS I wanted to avoid all this when I wrote “case closed!” How naive of me!

One more thing and I’m afc for a while: If I say that I like, I don’t know?, Iannis Xenakis?, people call me an elitist. I never understood this… is an elitist someone who doesn’t like trash and likes great art? Count me in!

On the other hand to say that kitsch is exclusively addressed to the low classes seems incredibly offensive to me. To say that is the real elitism.

Xenakis is awesome. And very apropos for talking about Frazetta!

I know you don’t hate all mass art. I didn’t know you liked Ford, though.

I’ve read a bunch of Kundera, including Unbearable Lightness of Being. It’s an informed aversion.

Noah — I guess where I differ from some critics of Frazetta is that while there is no denying much of his work was uninspired and created just to meet a deadline or fill some commissioned tasking, not all of his work falls into that category.

But there seems to be times when Frazetta dove deep into his id and pulled out paintings that were stand-alone works he did only to get some artistic vision out of his system — scratching an artistic itch, so to speak.

For example, Frazetta’s 1973 painting “Death Dealer” was not painted for any popular culture publisher or commission purpose that I know of. It seems to me like he only painted it because, from an artistic point of view, he felt he HAD to. Keep in mind that after Frazetta painted it in 1973, it sat in his studio for three years until he was profiled in an issue of the magazine “American Artist” and the editor apparently asked to use it for the issue’s cover. It was not until 1978 that the painting first appeared on a popular culture product: The cover of the record album “Molly Hatchet.”

In short, I would argue that “Death Dealer” was inspired art, and not at all kitsch.

And does it really matter if a 20th Century masterpiece adorned a paperback, album cover, or whatever? After all, if Rembrandt lived and worked during the 1930s, his paintings may very well have ended up as covers for “Colliers” or “The Saturday Evening Post,” rather than hanging in a church or on the wall of some businessman’s office.

It’s not fair for critics to punish Frazetta for living in the “wrong” era, and to judge him by a different standard than other artists.

Noah:

I love Ford and I’m delighted to find his influence in Barks.

It’s not _The Informer_ that’s unbearable though (I’ve seen it ages ago and I just remember the melodrama, ugh!), it’s _The Fugitive_, sorry!…

Don’t trust Noah too far on Kundera. Most of us have thumbs that comprise approximately 1/5 of our fingers

Oops, I just realized…when I mentioned John Ford as hyperbolic and trashy, I was referring to John Ford the english dramatist, not John Ford the American filmmaker. The later isn’t especially hyperbolic or trashy, I don’t think; the former definitely is.

At least Noah is consistent. It would have been a mild surprise to find out that he liked The Unbearable Lightness of Being. He would probably vomit if faced with Kundera’s Slowness.

Russ Maheras:

‘For example, Frazetta’s 1973 painting “Death Dealer” was not painted for any popular culture publisher or commission purpose that I know of. It seems to me like he only painted it because, from an artistic point of view, he felt he HAD to. Keep in mind that after Frazetta painted it in 1973, it sat in his studio for three years until he was profiled in an issue of the magazine “American Artist” and the editor apparently asked to use it for the issue’s cover. It was not until 1978 that the painting first appeared on a popular culture product: The cover of the record album “Molly Hatchet.” ‘

Well, no. ‘Death Dealer’ was used as the cover of the summer 1973 anthology of s&s fantasy short stories, “Flashing Swords!” #1– a damn fine anthology, BTW.

How would I know? Because I bought it the week it came out!

Frazetta…yes, kitsch is there, but you can’t reduce Frazetta to kitsch any more than you can reduce Charles Dickens or Victor Hugo to sentimentality. He’s too big.

Alex wrote: “Well, no. ‘Death Dealer’ was used as the cover of the summer 1973 anthology of s&s fantasy short stories, “Flashing Swords!” #1.”

Seriously? Never heard of it. Did the cover have anything to do with the anthology? That makes a difference regarding my argument for Frazetta’s possible motivations.

Speaking of that painting, the first time I ever saw it was in 1976, when I was working for the Chicago-area distributor, Charles Levy Circulating Company. A few of my co-workers were setting up the “Short Line” distribution for the newest issues of the monthly specialty/fringe periodicals with low demand (and thus, low distribution), and, as usual, I walked over to check them out.

When I saw that issue of “American Artist” with the “Death Dealer” cover, my eyes about popped out of my head. It was one of the most gorgeous covers I’d ever seen. And the article about Frazetta, which also featured a number of other full-color reproductions of his art, was pretty terrific as well.

As I recall, the entire Chicago area received only five 100-copy bundles of the issue, and after the retail dealer orders were run through the Short Line and filled, there were still several hundred copies of the magazine left undistributed. Since I knew that undistributed magazines were doomed to be shredded, and I knew, based on its low circulation, this particular magazine was going to obviously be a rare collector’s item, I used my employee 20 percent discount to buy 10 perfect, undistributed copies for $1.20 each.

Over the years, I sold or traded every copy but one, which I’ve kept to this very day.

That was one sweet, sweet magazine!

———————–

R. Maheras says:

But Domingos, you could use the very same argument you make against Frazetta against artists like Rembrandt.

How many paintings by Rembrandt were simply commissioned portraits of wealthy upper class or aristocrats? Considering HIS great painting skills, that sure wasn’t shooting very high.

I’m not sure why you have such a low opinion of Frazetta’s work, but I suspect it has more to do with the fact that Frazetta was active in your lifetime than anything else.

I suspect that if “Death Dealer” had been painted 500 years ago, your view of it might be very different.

———————–

I’m exceptionally fond of Frazetta (and have lots of treasured books to show it) but it hardly does him a favor to put him up against the Old Masters. As Norman Rockwell was aware, by rejecting those comparisons and calling himself an “illustrator” instead.

(And sure, the Old Masters routinely did “illustrations” of scenes from the Bible, history, and mythology, but the sense in which Rockwell surely meant it was to place himself in the mass-reproduction, mass-audience company of folks — pretty damn talented! — like N. C. Wyeth, Dulac, Rackham…)

Comparing those “commissioned portraits” that Rembrandt did with few Frazetta painted, the presumably personal-work self-portrait and paintings of Jesus are unfortunately telling. Frazetta shows splendid technical facility, but those touched by Rembrandt’s brush show the divine glowing within them; rich depths of emotion and inner complexity.

Frazetta’s a great illustrator; but painfully lacking in either the emotional/psychological/symbolic range, or innovativeness, or intellectual depth, which makes an artist truly great.

Frazetta’s “Death Dealer”: http://a1.l3-images.myspacecdn.com/images01/14/9ef0456d4e1074b75381d5f4e9c86449/l.jpg . Awesome, cool!

For a similarly equine-centered image, Rembrandt’s “The Polish Rider” (considered to be a depiction of the return of the “prodigal son”): http://www.wga.hu/art/r/rembran/painting/z_other/rider.jpg . What delicacy in the handling of paint, what emotional subtlety and mystery! A picture that, like the “Mona Lisa,” has inspired fascinated speculation for centuries.

(While with Frazetta, “what you see is what you get,” shoveled right into your face. Mysteriousness in his art is more akin to E.C. comics than Arnold “Isle of the Dead”* Bocklin.)

Raymond Chandler famously dismissed Alan Ladd (considered as a possible Philip Marlowe) as “a small boy’s idea of a tough guy.”

Alas, Frazetta would be (for all his splendid virtues; not to be dismissed as simply a purveyor of kitsch) a teenager’s, or motorcycle gang member’s, idea of a Great Artist: “That’s really badass!”

————————–

Alex B. says:

…yes, kitsch is there, but you can’t reduce Frazetta to kitsch any more than you can reduce Charles Dickens or Victor Hugo to sentimentality…

—————————

Indeed so!

* http://www.arnoldbocklin.com/images/The_Isle_of_the_Dead_1880.jpg