This is the second in a blog crossover event with Tucker Stone of the Factual Opinion focusing on Darko Macan and Igor Kordey’s run on Soldier X. Tucker’s first post on the last issues of Cable is here. After some preamble below, I talk about the first four issues of Soldier X.

___________________________

A little while back, Alyssa Rosenberg posted a piece in which she argued that neither Harry Potter nor Katniss Everdeen (of the Hunger Games) are particularly special in themselves. Instead, Alyssa argues, Harry and Katniss are important because they are used as mascots for a larger cause; they inspire others.

The reason Harry Potter is the main character in the series isn’t that he’s awesome — to the contrary, he’s a fairly average kid, and Snape’s assessment of his overall abilities as a wizard is probably correct. The idea that he’s extraordinary — and really, that extraordinary things can happen in the cause of righteousness — inspires other people to rise to and above their potential. The most interesting moment in the entire series is when he’s presented as dead to the people who have been fighting for him — and they keep fighting, in particular Neville Longbottom, who exists as an illustration of the arbitrariness of Harry’s prestige, and who rises to the occasion, killing the hell out of Nagini even when he’s been set on fire. Ron dashes down to the Chamber of Secrets and just pretends he knows Parseltongue, and it works: again, Harry’s not magically special, but the special things he does inspire people to try crazy and unusual things.

I think Alyssa is right diagetically. Harry isn’t a great wizard; he isn’t presented as being especially strong or smart. He’s a great Quidditch player, and he’s kind and brave, but he’s not a super-hero in the usual sense. He’s more important because of what he symbolizes than because of what he can do physically.

But that somewhat begs the question — why is Harry so important symbolically? Of course, the narrative answer to that question is that Voldemort tried to kill him as a baby and failed. But there’s an extra-diegetic answer as well. And that answer is — Harry Potter is the inspiring symbol because his name is on the cover of the books. He’s the hero not because Rowling’s world has chosen him as a hero, but because Rowling has. Harry’s real super-power, the reason he is special, is that he’s got a direct line to God. It’s more than mere fame; it’s the fact that the universe is about him. It’s like that scene in the Hitchhiker’s Guide where Zaphod Beeblebrox sits down in that machine and discovers that, yep, just as he always thought, the universe was in fact constructed expressly for him. In book after book, it’s Harry who runs across Voldemort, Harry who just happens to be in a place where courage and luck can hand him victory, Harry who, despite not really being all that, gains more and more status through more and more convoluted plotting as he triumphs again and again not because he’s especially smart or powerful or clever, but simply because he’s the star.

The point here is that, contrary to Alyssa, Harry’s specialness has little to do with the workings of political movements, and a lot to do with the workings of serial fiction. In The Hunger Games, for example, which Alyssa also discusses, Katniss Everdeen is skillful and brave and resourceful — but her real importance is that she’s the narrator and star, and so Suzanne Collins keeps putting her in situations where her decisions have world-historical implications, because that’s what you do with your narrator and star.

Now, in light-hearted fare like Tintin or the How to Train Your Dragon books, the fact that the unassuming main character keeps stumbling into Very Important Situations is part of the lark. Harry Potter and the Hunger Games, though, both have pretensions — and thus, inevitably, both series struggle more and more under the weight of their own preposterousness as they go along. Voldemort’s elaborate plan to enmesh Harry in the tri-wizard tournament, or President Snow’s elaborate plan to enmesh Katniss in the Hunger Games again…they both make little sense from the perspective of an actual villain who wants the protagonist dead. You want to kill someone, you kill them; you don’t construct an elaborate game which takes a whole novel to elucidate.

But elaborate games make a lot of sense from the perspective of the watching demiurge who wants the protagonist to have a chance to demonstrate his or her glorious bravery and wit and angsting. Along those lines, when Ron gets all pissed at Harry because Harry is always in the thick of everything and it’s not fair, you can’t help but feel that the kid has a legitimate grievance. It really isn’t fair — and the fact that it’s such flagrant special pleading incidentally makes it a lot less fun to read. Harry doesn’t need superpowers because he’s got the greatest power of all — that of a rolling Mary Sue ex machina.

___________________

And, in case you were wondering, that finally brings me to what I’m in theory supposed to be talking about.

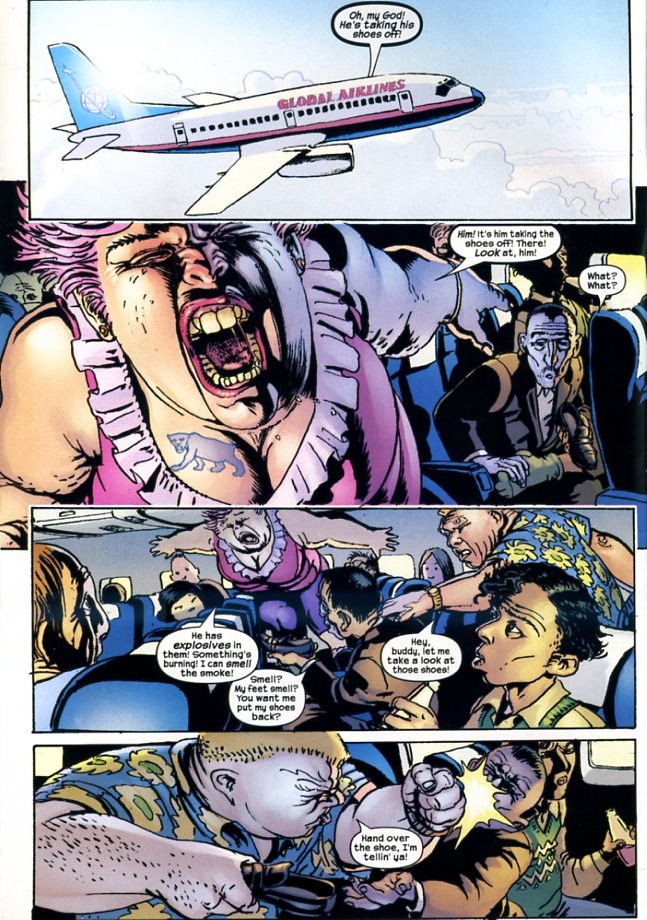

Soldier X opens with a slapstick post-9/11 panic moment as artist Igor Kordey draws a gaggle of cartoonishly bulbish American bodies straining against the narrow panels of an in-flight airline. The bovine panic has been inspired by what the copilot exasperatedly refers to as “Another false shoe alarm.” As the sea of human idiocy flexes and dilates, one young woman types intensely away on her computer, undeterred by ricocheting flight attendants. Said young woman is, it turns out, writing a story at the last minute for the Daily Bugle about a copyright conference…a story she failed to write earlier because she was pursuing leads on Nathan Summers, aka Cable, aka our protagonist.

Thus, writer Darko Macan starts off, first page, first issue, by presenting his hero as a distraction from a distraction from the main action. The result is that you feel strongly that Macan and Korday would rather be focusing on ugly Americans and their cowardice, or even about a copyright conference, but instead are stuck writing about some idiotic super-hero with an incomprehensible backstory in order to pay their bills.

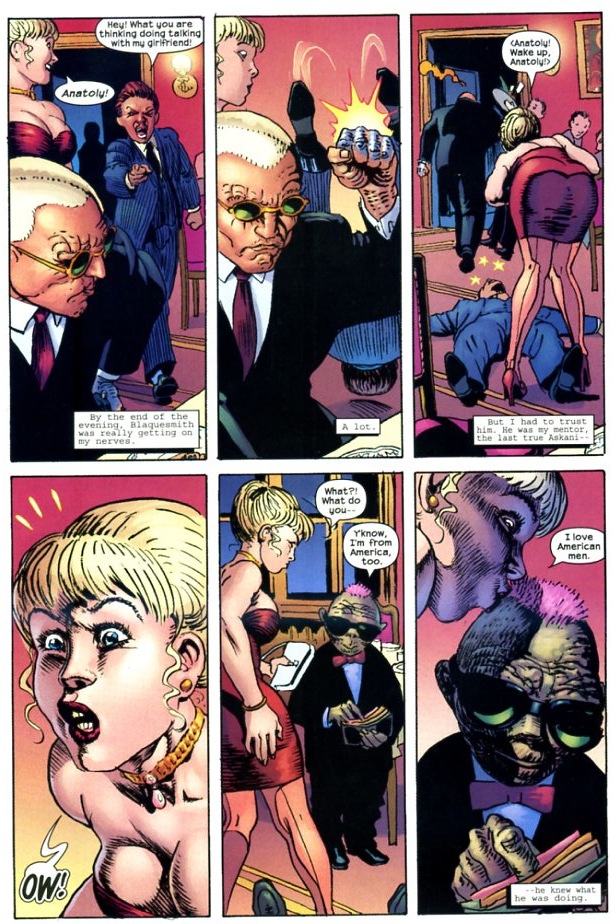

And so it goes throughout the first four issues, more or less. Incompetent agents of SHIELD show up tossing out lame puns and incompetently impersonating ninjas, only to be dispatched by a sumo wrestler in a Sailor Moon suit — and then it’s all spoiled when you have to go back to the superhero title and hear Nathan nattering on and on about how he hasn’t killed a man in two years and blah blah blah, here, let me drop trou so I can dump a giant pile of who-gives-a-shit on your doorstep, hokay? Or, alternately, we get gratuitous dwarf porn and ass-shots of bodacious Eastern European prostitutes, and you say, okay, this is clearly what Mr. Kordey wants to be drawing — but then it’s over and we’re back to some dumb noir patter and watching Cable throw people around with one of those powers and endangering the fabric of our shirts from the repetitive shrugging of compulsive indifference.

At its best, the effect here is one of conscious parody. Nobody but nobody actually cares about Cable the way millions of people care about Harry Potter, and the only one not in on his own utter insignificance is the big dumb ox himself. Cable acts as if he’s the star of the book and even of the universe; he assumes that his main power isn’t telekinesis or big bad guns, but rather the reader’s, and especially the author’s, attention. He thinks he’s Harry Potter, or Katniss, or Superman — that People in Charge care deeply about his angst and his running internal monologue. And, again and again, the People in Charge laugh at him for being a boring dimwitted narcissist, so involved in the endlessly fascinating genre conventions of his own omnipotent navel that he’s unable to notice that the groundlings just want him to fuck off so they can get on with their own crappy lives.

The problem, though, is that the book can’t ever actually tip over into parody; Macan can write insouciant recap pages upon which Kordey can draw gratuitous T&A, but the rest of the book has to at least pretend to be a mainstream Marvel title. And what that means is that Cable’s attention-whoring has to be validated. He not only thinks he’s the most important person in the universe — he actually is that person. That reporter at the beginning of the series is obsessed with him; the SHIELD agents are obsessed with him; various bad guys follow him around as if there’s no other superhero in the world for them to pledge their undying animosity to.

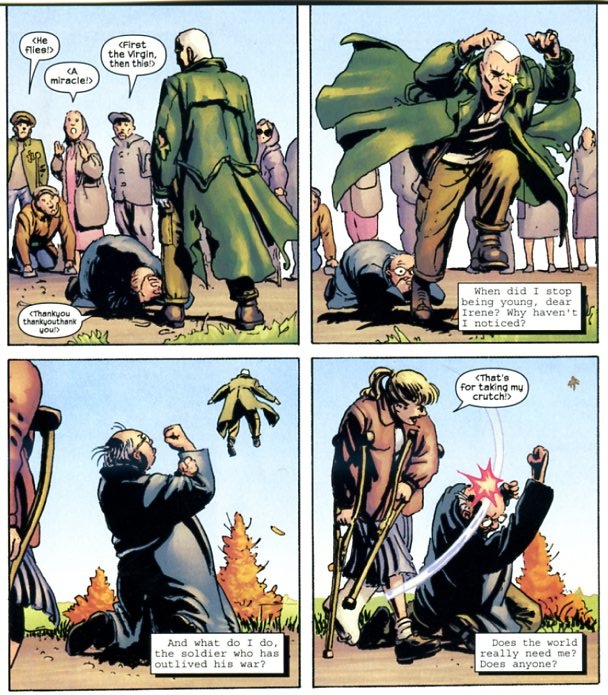

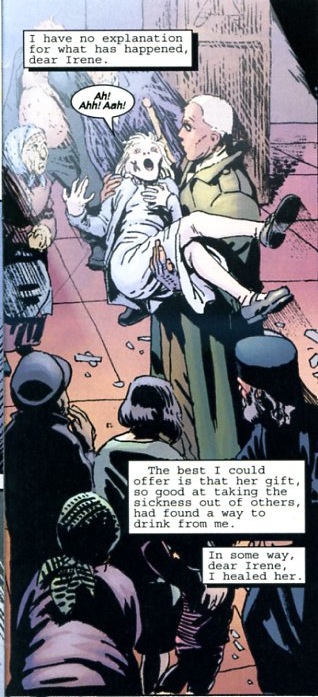

By the fourth issue, the tension between the impulse to cut the star down to size and the genre demands to puff him up seem to give the series something like a creative breakdown. Cable turns into a Christ figure, actually healing the dead, as his internal text blocks achieve an apotheosis of banality (“And this exhilarated me. Scared me. Made me think….This makes you really, really think.”) Macan’s leaping up and down in his underwear screeching, “Pay no attention to that Yahweh in the corner!” while Kordey draws the Resurrection as conducted by a deity whose jockey-shorts have risen up abruptly and uncomfortably high. Both of them seem more than a little desperate, like zombies staggering about in the post-apocalypse searching clumsily but earnestly for their own spilled brains.

Alas, grey matter in comicdom is apportioned out only in precise amounts. The name on the cover is not just a title; it’s a command. Those letters are as big as your world can be, and while Soldier X may not be able to turn your appendix to butterscotch, he can, like Harry Potter on a much smaller scale, do what is worse — whine and make you read it.

________

Update: Alyssa has a fun response to this post here.

Update the second: you can now read the complete blog back and forth. Here’s my part. Here’s Tucker’s part.

The story has a happy ending, though, because Cable was eventually relaunched (with Deadpool) as a buddy comedy. XD.

Was it any good? I don’t hate the Soldier X ones; it just seems like they could be better if Cable weren’t in them.

My comic book liking friends love Cable & Deadpool. The joke of the series is that Cable has one of the most convoluted and srs-bizness backstories in all comicsdom, while Deadpool is kinda ADD and just wants to go out and cause mayhem.

You can get a sense for the love (including the slash love) here:

http://scans-daily.dreamwidth.org/tag/title:+cable+%26+deadpool

Hmm. I was sort of hoping it was something where Cable would have a maudlin textblock and somebody would hit him really hard. Over and over. That would be sort of satisfying….

Those pages are, um, strangely well-drawn.

The Kordey pages you mean? He’s really quite good; nice aptitude for imaginative caricature. And yeah, it’s weird to see that in a 2000s mainstream title.

Especially this post!

http://scans-daily.dreamwidth.org/2746926.html

I think it’s making fun of the backstory more than the character, but I’d have to ask my comic book liking friends to be sure. As half of a comedy duo, Cable is the “straight” man.

——————

James says:

Those pages are, um, strangely well-drawn.

——————-

Yeah; there’s a nice Richard Corben influence in places: https://hoodedutilitarian.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/soldierx172.jpg

(The slightly squat figures, unfussy linework, touch of caricature…)

“The joke of the series is that Cable has one of the most convoluted and srs-bizness backstories in all comicsdom”

SRS? You mean sexual reassignment surgery?

If only it were so. But for all Cable’s convoluted backstory, I don’t think there’s anything that interesting in it.

More like this:

http://cheezburger.com/View/1934388480

I think the official spelling is ‘srs bsns’.

For a good idea of what the Cable & Deadpool books are like, check out the AMazon review of the Ultimate Collections that begins with the line, “A 50 issue ‘buddy-movie’ starring the Marvel U’s equivalents of Jesus Christ & Bugs Bunny.”

Pingback: Living Safely in a Fantastical Universe