For certain of us, the thrill of opening a comic book cannot be overstated. Particularly if the page is crammed with dynamic lines, swirls of motion, color and a plethora of panels. Instantly, our pulses race. Immediately, synapses begin to fire. We are overwhelmed by the scope and variety of the material before us and we savor the moment before our rational, superior divided-self checks the terror of confusion and steps over the direct and unarticulated response to the material to communicate the simultaneously terrifying and exciting instant of speechlessness. We perhaps articulate that moment with “Cool” as we hover between pain and pleasure. We experience the sublime.

Edmund Burke, a clever man, thought at length about the sublime[1] and developed certain theories about how humans take in visual stimuli:

VISION is performed by having a picture, formed by the rays of light which are reflected from the object, painted in one piece, instantaneously, on the retina, or last nervous part of the eye. Or, according to others, there is but one point of any object painted on the eye in such a manner as to be perceived at once; but by moving the eye, we gather up, with great celerity, the several parts of the object, so as to form one uniform piece.

The unknown writer of Bernard Krigstein’s final comics work 87th Precinct thought about this too and produced the following intersecting and bizarrely Saussurean commentary :

But to return to Edmund Burke for the moment, he wants to think about a painting, and more importantly for us, a single object and how its representation would be taken into the eye:

If the former opinion be allowed, it will be considered, that though all the light reflected from a large body should strike the eye in one instant; yet we must suppose that the body itself is formed of a vast number of distinct points, every one of which, or the ray from every one, makes an impression on the retina. So that, though the image of one point should cause but a small tension of this membrane, another and another, and another stroke, must in their progress cause a very great one, until it arrives at last to the highest degree; and the whole capacity of the eye, vibrating in all its parts, must approach near to the nature of what causes pain, and consequently must produce an idea of the sublime.

Today Burke’s ideas on the function of the eye in apprehension seem amusing, but he raises interesting points that touch the optic nerves of many comic book artists and readers.

There is some theoretical talk out “there,” in the sublimity of discourse concerning how the comic page is perceived, but I find that like our eighteenth century predecessors who made admirable attempts to codify or to supply language to visual experiences, there remains a dearth of language available with which to tackle certain experiences. I remain unable to find any language that addresses the moment before we begin the instinctive work of decoding what we see. That it is a form of the sublime I am sure, but this does not give language to the effect. After the first consumption of the page in its entirety comes a focus to determine the form of the page, a first step in the decoding. Yet, it seems there is not diction for these interstitial movements and this will become a greater problem, because it will affect how we understand comics and the relationship of the image to text into the far-foreseeable future. It will limit how we are able to articulate the seminal first moment.

Our inability to express how we see text and image in relation to each other still requires work. I am not suggesting that this necessitates an infinitude of new expressions; we do not need to find a thousand ways to say white, although perhaps the Alaskan Inuit were onto something. (In previous posts, I have shown white panels, and there are many examples from which to choose, whether empty or filled with white.)

In considering this issue, I recalled the use of Flash cards, which became an annoying part of my life when my son was in Pre K, inasmuch as other parents felt free to flash them at random during any conversation. Here, the act of offering an image to symbolize text is described by flash, but the action of the child upon whom this ocular violence was enacted was given no particular name for their reception of the image. So that from early childhood we are left without words to accommodate that primary moment, before assimilation. The next step of what was meant to happen, “learning,” found linguistic form, but again the first step in the process has no particular vocabulary to describe it. One does not hear: “when I thrust my flash card into the range of sight for my child he or she immediately perceived the textual, spatial, object relations to supply language.” It would be silly since it would be out of place, but where it would be helpful in the discourse of comics, when we avail ourselves of the pleasure of the first flash, our response remains unnamed.

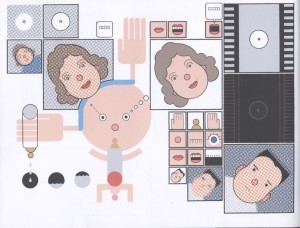

Chris Ware’s Lint: a diagnostic of the acquisition of language: in the startled / blank eyes of the infant can we register prelinguistic sublimity?

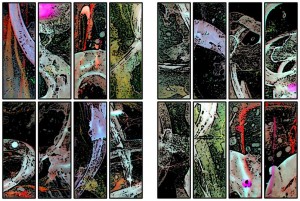

“Apprehend” might be close to what is required, but still it seems too much tied to the first stage of interpretation of the material. Andrei Molotiu produces some interesting abstract comics that extend that moment of apprehension, since the mind is unable to rest, or find comfort in the ciphers that it makes. There is a suspended moment that recalls the sublime in certain respects. The work at the very least challenges the limits of reception and formal responses to comics. Douglas Wolk [2]writes of the anthology of Abstract Comics compiled by Molotiu that “it’s a fascinating book to stare at, and as with other kinds of abstract art, half the fun is observing your own reactions: anyone who’s used to reading more conventional sorts of comics is likely to reflexively impose narrative on these abstractions, to figure out just what each panel has to do with the next.” Wolk’s observation is helpful as he grapples with the first response and the challenge that abstract comics present. His use of the word “stare” both signals a stalled but receptive state, yet it allows one to return to the way that we experience a page before we enter into its complexities. The moment that presages the “stare,” whether in abstraction or narrative comics does not yet differentiate between the two. We have not had time to seek faces, identify text, or to participate in the experience of the page on any level than that of its visual inter-kinetic.

Andrei Molotiu provides a space in which we can linger on the verge of another mental state of apprehension.

Part 2. Focus on the Eye.

Edmund Burke’s insistence upon the physical response to visual stimuli in the outside world has remained more entrenched than one might suppose, particularly within the realm of cartoonists and artists. Artists whose work relates singularly to representation of objects seen or imagined, frequently draw upon, or just draw images of the eye to connect their characters with their constructed outside world. Perhaps for artists there is a deep-rooted fear in any trauma to the eye, which informs their identity as their livelihood requires that they “look” and “see,” which I understand as separate actions. This is not solely my distinction, it is a Miltonic reference, in that man must look and see his world, the second part, see, meaning comprehend, or internalize the meaning of what man is shown by higher powers. We expose ourselves to the pleasure of the page in anticipation of that experience of catharsis. And here I will diverge from any more highly aesthetic or spiritual understandings of what is happening, to suggest instead that we are animalistic in this pursuit. We act primarily to satisfy the limbic brain; to fulfill the impulse of the deep primitive brain. This brain causes us to pre-cognitively, visually graze for stimulus so that we can trigger the pleasure response. Comics are part of our system of desire. Animators apparently made this link and described the anatomy of the active “graze” that prefigures the “gaze” to hilarious effect. In Tex Avery’s brilliant depiction of the wolf looking at the songstress there is a pause before the wolf gathers the import of what he is seeing. There is a pause before his eyeballs pop out of his head. Sex and comics…well, both are sometimes both painful and pleasurable.

Avery’s wolf scans the female form as some of us do the page; hungrily before we can calm down to think rationally about what we are seeing.

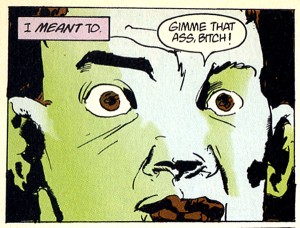

Doselle Young/ Tony Salmons/ Sherilyn Van Valkenburgh, Jericho, HeartThrobs :

Out of control: Already consumed in the pleasure of reception.

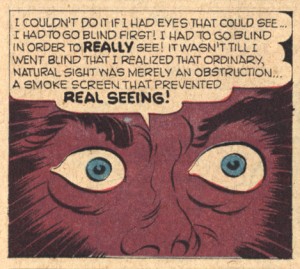

Elsewhere, the tension of sight and meta-engagements in depictions of eyes as signals of human responses litter the pages of comics with a startling degree of anxiety. Recall my earlier quotation of Burke’s:

So that, though the image of one point should cause but a small tension of this membrane, another and another, and another stroke, must in their progress cause a very great one, until it arrives at last to the highest degree; and the whole capacity of the eye, vibrating in all its parts, must approach near to the nature of what causes pain…

Archie Goodwin/Steve Ditko, Collectors Edition, Creepy #10 famously demonstrates anxiety about the eye’s pain sensitivity .

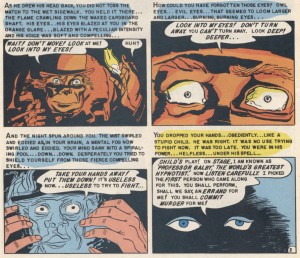

Al Feldstien/B Krigstein/Marie Severin, You, Murderer, Shock Suspenstories #14 offers a representation of the ineluctable power of the eye and its ability to penetrate the human body and mind and to override our deeper impulses and will.

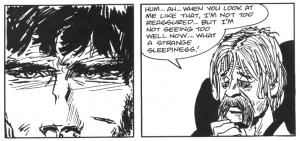

Hugo Pratt’s Banana Conga allows us to perceive how much of own volition and active consciousness is accessible to us in respect to the gaze.

Perhaps, finally, one must consider the agreement of the reader to the contract between himself and the comic artist; a relationship much desired by the artist who craves the interchange. The many demonstrations of ocular distress in comics perhaps reveal how deeply the artist is aware of the commitment of this particular form of intimacy, or the risk of abandonment. Conversely, for readers there is an agreement to relinquish part of our civilized nature when we agree to look at a comic. The anticipation of pleasure that precedes the viewer’s acquiescence to employ his powerful sensory aperture, the eye, is a self-revelatory act. Every time we open a comic, we stand before it in our savage nakedness. As readers, we too risk disappointment; that the pages might fail to deliver. Let us not forget that in comics we want the words as well as the pictures; we want it all. We want the whole package.

[1] Burke, Edmund. A Philosophical Enquiry. Part IV. section 9. UK : Oxford University Press, 1990.

[2] Douglas Wolk, New York Times Book Review, Holiday Books edition, December 6, 2009

Not so long ago, visual psychologists used to think there were two visual pathways: the ventral, which processed “what” things are, and the dorsal which processed “where” they are…but according to wikipedia, that theory is *so* last season.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Two-streams_hypothesis

Actually, it sounds kind of like you’re looking for a term like “sense-data” as it was used in 20C analytic philosophy, or Hume’s “impressions”. These are, in at least some variants, supposed to be pre-interpreted stimuli; in some sense, what is “directly given” to us in perception. Some sense-data theorists thought/think that the pre-interpreted content of experience is something like “red patch at so-and-so position of my visual field”…which might be the sort of content you’re talking about.

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/sense-data/

Not that cognitive psychology or analytic philosophy are too popular around here…

“Not that cognitive psychology or analytic philosophy are too popular around here.”

Dear Jones,

This is why I think a “language” of comics needs to be fostered. In much the way the structuralists, with all their flaws provided a framework from which to build. The aesthetic diction for the study of comics should relate to the medium specifically, not borrow from other media genres, film for example has a wonderfully rich vocabulary. Nor should we have to beg from psychology, cognitive or otherwise because comics are unique. They are not like films, videos, novels or paintings. Current arguments about writer and artist tensions and collaborations will continue to circle the particular elements that make comics unique if the language does not frame the issues.

This is fairly polemic for some I’m sure, but the fact remains we seem to come up short. James Romberger wrote about James J.Gibson, who has some interesting things to say in his essay on visual “affordances” but it still is insufficient to meet my demands.

http://www.thearteriesgroup.com/ParametricImages.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_J._Gibson

In film Cristian Metz carved a path that has been extremely useful, like it or not. I am suggesting that parallel work needs to be done in comics, but perhaps finds a better way to talk about the visual in proximity to the verbal. In a sense there is a moment of freedom here to formulate, create, design, what ever you want to call it, the basic element of how we cope with the alignment of images and text on the page.

To split terminological hairs, I don’t think the visual in comics is any more proximate to the verbal than it is in film. If I understand you correctly, what is proximate is the visual to the orthographic. And visual is a bit broad as well, since as you point out, the drawings can resemble their referent (or at least signify it by way of established viewing codes), or it can be wholly abstract.

As to the event of initial seeing, and the question of what happens before the work of interpretation begins, this is a question that transcends medium. As such, a turn to cog sci/psych, phenomenology, or whatever, seems perfectly appropriate.

Or, maybe I’m misunderstanding your objection to Jones.

Nate: “I don’t think the visual in comics is any more proximate to the verbal than it is in film.”

In film the aural is a factor, in comics text and image are on a page, both, to be assimilated visually. I would suggest that reading and viewing a comic is more visually and linguistically complex in certain respects,(only some, let me qualify this). In film, sound and image do not require that the subject make decisions about whether to listen or to look, but we must make that determination in comics. Additionally, we have to determine the geometric narrative. There is a constant movement between these fields of re/cognition, a back and forth between numerous factors.

Nate: “As such, a turn to cog sci/psych, phenomenology, or whatever, seems perfectly appropriate.Or, maybe I’m misunderstanding your objection to Jones.”

While I can largely agree with Jones, his point about the comic scholar’s anxiety with respect to cog sci/psych is well taken and this indicates to me that (simple) acts in response to a comic are unnecessarily challenging to communicate. Even if we agree to go cognitive areas for the physical or phenomenological explanation of the process,I think that we miss some rich elements and are steered away from the continuity of responses specific to comics.

Seen from the other side there is no language that I’m aware of with which to talk about the whole page as a single unit: architecture, narrative images, text and sound effects.

This is something that Jim Steranko thought about and discussed during a series of conversations with James. I’m including the quote:

Steranko: The limitations of printing MED1ASCENE (2 color, size, etc) dictated the elements used in the creation of FROGS. My intent was to produce what I frivolously called a “poster story” or story in a single unit and designed specifically as a double-page in MEDIASCENE, every panel could be seen SIMULTANEOUSLY when the page is held in reading position. The mind instantly assimilates all the information and begins processing the data–subconsciously. And, as the eyes track through the panels, focusing on the details of each image, the mind makes a conscious pass AT THE SAME INFORMATION already covered–but now, attempting to PROCESS it into a classic narrative structure. This creates an INSTANT COLLABORATION between the author and the reader, one that puts a much greater demand on than film, for example. The result is ultimately more satisfying (in most cases). I could go on, but you get the idea.

It is pretty hard to define the moment Marguerite is talking about, the split second as someone is looking at an image, before they actually process the image. Visual perception is most often discussed under the umbrella of psychology; Gibson is cited because his studies revolved around his involvement with military test pilots, who must make decisions quickly based on limited visual information. This is why color is so important in comics, it forms the bulk of the immediate impression the viewer has. What one sees as they open a comic is an arrangement of interlocking color forms, similar to looking at a painting in a museum. The text is not read yet, one performs a skimming, a pre-mapping of the image. Jim’s “Frogs” is on a single double page spread so it is designed to be taken in at once in its entirely. Still, the subsequent actual mapping proceeds immediately. So I think Marguerite’s “precognitive graze” fits that initial moment quite well.

I’m going to go over this more carefully but man, James and Margerite. Very few people are aware of these ideas and presentment in narrative. These underlie and enforce story on a mostly unconscious level.

In the ’70s there was a study (which I can’t reference now) that noted a reader looks at each image a matter of 2 1/2 seconds before reading the balloons and going to the next 2 1/2 second image. Daunting for such as we who labor hours over each image in series. Still the astute mind of the storyteller is very aware of these fundamentals. They’re powerful beyond words because they are pre-verbal and non-verbal. The ideas go directly to vital mind of the viewer, bypassing logic and argument and qualification. It’s a wizard’s role we play.

Wonderful discussion.

And you’re right, Marguerite. Comics are distinct from all other media. They may be informed by other ideas and disciplines but comics is clearly unique. Despite “workhouse” conditions and company dominance that produced much of them in the past, comics remains the province of auteurs, like very few efforts in media. A comic “book” may be made at your kitchen table (and most are) or in any soiled public restroom where the real meal is prepared ’til the next one. From the (perceived) highest to the (perceived) lowest the voice of the individual is nowhere more represented. And fantastically arrayed. She calls from rocky shores.