In their essays on the recent appreciation of Jaime Hernandez at the TCJ website, both Noah and Caro ask, What makes JH’s work a masterpiece, and if you can’t tell me that, then why should I, as a potential reader, care? These are good questions. And I’m going to provide an answer that, in the spirit of HU, should piss-off just about everybody. Ready?

In their essays on the recent appreciation of Jaime Hernandez at the TCJ website, both Noah and Caro ask, What makes JH’s work a masterpiece, and if you can’t tell me that, then why should I, as a potential reader, care? These are good questions. And I’m going to provide an answer that, in the spirit of HU, should piss-off just about everybody. Ready?

The TCJ appreciation is not about Love and Rockets but its readership. This is necessary and also unfortunate.

Before I go on, let me clarify two things. First, I’m using the term masterpiece in its colloquial sense, as in a superlative work. I’m not going to worry over canon formation here, nor am I going to suggest the need for criteria for determining worth relative other works. Second, by arguing that that TCJ roundtable is about the readership and not the comic, I don’t mean we should disregard it. As will become clear, I think Love & Rockets is, and always has been, part of a conversation about what comics can be. To read Love & Rockets without reading the conversations about it would be to read only part of Love & Rockets. Basically, I’m arguing that the quality of the comic book Love & Rockets is less important than its role in creating a reading public of a certain character, bound together by their shared attention to the comic.

This argument derives from the work of Michael Warner, whose book Publics and Counterpublics argues that publics are the outcome of texts that address them as such. So, I’m going to offer a quick and dirty account of Warner’s theory of publics, explain why it is important to understand contemporary North American comics not simply as works of art, but as loci for the formation of publics, and finally, why assessing the quality of Love & Rockets is, in many ways, beside the point of the TCJ Roundtable. I’ll also argue that this is OK.

Warner makes the case that a public is created by shared attention to text. Texts, he argues, “clamor at us” for attention, and our willingness to pay attention to certain text and not others determines the publics we belong to” (89). By giving our attention to a text we recognize ourselves as part of a virtual community bound by that shared attention, and as part of an ongoing conversation unfolding in time. The classic example would be the local newspaper, which in addressing its readership constitutes each reader as a member of a locality. The daily paper does this because it encourages readers to imagine themselves as part of a virtual community, defined by a common civic-mindedness and a commitment to that text as a way to make sense of the multiple texts affecting their lives. They do this not only through reading but also through letter writing, impromptu conversation, and so forth. The daily newspaper metaphor points to another aspect of the relationship between texts and publics; namely, the publics constituted by texts “act according to the temporality of their circulation” (96). The daily rhythm of the paper is a daily reminder of one’s status as part of a public, a status that is part-and-parcel of one’s identity.

The flipside of this is that if the text ceases to receive a level of attention necessary to sustaining it, not only does it go away, but so too does its public, and with that public, a part of each member’s identity. Understood as such, it is easy to see why the cancellation of a TV show, magazine, or comic book creates a level of anxiety seemingly disproportionate to its quality as an artifact. Publics exist by virtue of attention, something that in today’s world, has been stretched incredibly thin. We’ve got many, many texts vying for our attention. Moreover, traditional rhythms of circulation have been thrown out of whack by innovations in comic book publishing, and, as Warner himself notes, the Internet. But I’ll get back to these points in my discussion of the TCJ roundtable. Now, I’m going to explain why this theory of publics is crucial to understanding North American comics.

Here’s a bold statement that is likely as false as it is true: North American comic books have, until very recently, been a means to public formation first, and a art form second (if at all). And this includes Love & Rockets. I’m not an authority on comics history, but my understanding is that superhero comics took off in part because they were created and edited by members of the science fiction community—a public constituted by fanzines—who understood itself as defined by its devotion to a textual form that many in society treated with contempt. This sense of community was fostered in letter columns, fanzines, and eventually conventions. It’s even easier to see public formation in Marvel superhero comics… Stan Lee addresses the readers as friends, in on the joke, but also serious about what the text they’re reading means to them relative other publics (true believers vs. everybody else). He directs their attention to the history of his comics’ circulation, he answers letters, and he asks readers to find mistakes in continuity. In exchange for their attention to the minutiae of circulation the careful reader receives a “No Prize,” as if to say that attention is a reward in itself. After all, its what makes you part of a public, which is what makes you who you are.

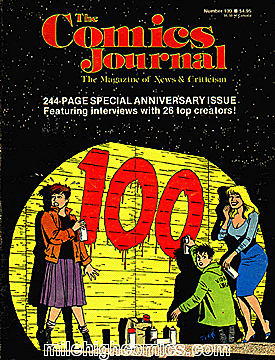

Love & Rockets emerged at a decidedly different moment in comics’ history. This is important because, as you will recall, publics act according to the temporality of their circulation. The public L&R addressed was the public bound together by the ruminations of The Comics Journal, and of other comics aspiring to a level of artistic sophistication that had yet to be realized in a significant way. It was, in short, a text that in its initial incarnation constituted an audience in a manner consistent with its aspirations for the medium. It was part of the medium, inasmuch as it came out regularly, ran letters, and so on. But unlike the superhero comics that surrounded it on the racks, Love & Rockets did not assume a new readership every five years. Nor did it require a status quo be maintained in order to insure the brisk sales of toothpaste and hastily cobbled together cartoons. In short, it promised comics readers a text that would reward sustained attention, and honor their identity as part of a community of readers over the long term. (This suggests that Dave Sim’s commitment to 300 issues was crucial to constituting the incredibly robust public constituted by Cerebus. But that’s a whole different post.)

What is remarkable about Love & Rockets is that it has made good on this promise for many years. Moreover, its publisher’s commitment to keeping the books in print has made it possible for the public to grow. And aside from the occasional detour, Jaime’s central storylines continue, which allow for the renewal of a reading community… a public that understands itself as defined by its ongoing attention to the text. This is no small thing in an age when publics from and dissolve according to the logic of direct-market orders and cross-media synergy.

That said, the rhythms of its circulation and appreciation have been disrupted by changes in the comics market, and in the forums for discussing it. When Love & Rockets began, it’s public entered into a relationship with the text fostered by the weekly trip to the comics shop, the letter column, and fan magazines like TCJ. As Frank Santoro pointed out in his “The Bridge is Over Essays,” Love & Rockets is no longer part of a larger community of comic readers. It comes out as a book now, and not in a monthly pamphlet. This isolates its public from the institutional frameworks that incubated it. Similarly, with the end of TCJ’s regular publication in print, and the balkanized world of online criticism, consensus about what comics are worth reading, what comics criticism should look like, etc. The public constituted by Love & Rockets is understandably nervous.

This talk of publics, and the disruptions to Love & Rockets rhythm of circulation leads me to why I think the appreciation is necessary, but also unfortunate. The roundtable in necessary because it does what public must periodically do to maintain itself in the face of threats to its existence. Hernandez just produced a work that by his own admission he will have trouble following up. Absent the imperative to monthly publication, and of a regular, print forum for praise and blame, the burden to compel the effort falls to the public that exists because of it. What we are seeing here is epideictic rhetoric, an effort to affirm a public’s taken for granted ideas in order to argue for why Love & Rockets should continue.

The appreciation is also unfortunate. It is unfortunate because is relies on shared and implicit assumptions to bring the community together, which in turn implies a certain “you had to be there” exclusionism. In this respect, I agree with others that more attention to the “why” of Love & Rocket’s value would have been salutary to the goals of the appreciation. In this respect, the appreciation was a missed opportunity to expand the public.

Ultimately, I think we have here a really interesting example of the intersection between artistic form and ritual performance. That it inspired the HU to go off on taken for granted values (Love & Rockets as soap-opera in particular) also suggests that whatever threat the Internet poses to this public, it also puts it into a larger conversation. So, while the bridge between publics is gone, its been replaced by a confusing, and to my mind much more interesting, network of bridges.

_____________

This is part of an impromptu roundtable on Jaime and his critics.

Could someone here explain why it is that comics are held up to the standards of an undefined “canon” here?

No one writing here seems to hold the things they like up to this undefined canon, only the things they don’t like.

Everyone here with the exception of Domingos likes all sorts of popular material which Domingos would no doubt dismiss as detritus.

And would Domingos place Hugo Pratt along side the hidden canon which as I understand it might include work by Rembrandt, who some people think doesn’t understand foreshortened perspective. Proust, whose work is seen by some critics as mostly a bore. Picasso, who is pretty commonly dismissed as a fraud, and Shakespeare who may be two or three people according to some critics.

Well, if this “canon” is going to be invoked on a regular basis, then maybe all here should compose a personal canon, publish it, and judge everything against it.

Is there anything in any medium being done today which holds up judged against Cervantes?

I don’t think most folks here are especially interested in canonicity? Or I guess it probably varies; Domingos and Robert Stanley Martin are; Suat maybe is, I’m not so much. And, in any case, different people on the site have really different ideas about what is good and what isn’t (as you may have noticed if you read the looong tussle over Tarantino in the recent comments threads.) That seems healthy to me…I’d hate to publish some sort of canon that everyone who wrote for the site was supposed to sign on to. Different people are coming from different places; that makes for more interesting conversations than if everyone agreed on Domingos’ canon, or on the greatness of Love and Rockets, or whatever.

For what it’s worth, I like Picasso fairly well; Rembrandt a lot; Shakespeare a ton…and the idea that Shakespeare isn’t Shakespeare is in general considered laughable (outside of the couple of plays that Shakespeare avowedly collaborated on, of course.) And Cervantes is great.

There are some comics I think hold up well against just about anything; Peanuts especially. The issue for me, though, is less creating a canon than it is insisting that comics should be thought about in terms of a wider artistic community and practice. So I think it’s helpful to think about Jaime in comparison to soap operas and Quentin Tarantino and, sure, Shakespeare or Charles Schulz too. The point isn’t necessarily to use those comparisons to denigrate Jaime’s achievement (though it can be, sure) but to think about what that achievement is and how it functions not just for the comics community, but for others interested in culture and art and possibly even in the wide range of things that aren’t necessarily culture or art.

Nate’s point, I think, is that sometimes you need to consolidate a subculture, or a fan base, before you can have a wider conversation, in part so that there’s a market/audience for the art in question. I guess I’m a little skeptical…it just seems like comics has gone the consolidation/subculture route for so long (as Nate admits) that further progress along that road threatens to become sclerotic. Your own resistance to the very idea that comics might be compared to other arts seems like a case in point; why shouldn’t they? What’s so outrageous about the idea that comics should be discussed in the same breath as Picasso or Shakespeare? I just think at some point when you circle the wagons like that you end up not being able to get out of the circle.

But anyway…Nate’s more or less on your side, I think, which is hopefully some consolation…

Noah, But it wasn’t comics but the whole of modern culture which I’m pointing at.

And it isn’t one canon to be signed off on, but individual canons I’d be interested in seeing.

Who is todays Picasso? Where is the modern Bard?

The thing is I only see this canon broadside fired at things people don’t like, never even aimed at stuff like The Watchmen, television, or pop music.

There is nothing wrong with firing the canon. By all means if it’s going to be used then it should be used everything in modern culture should be a fair target.

The last time the HU “hive mind” was evoked Jeet Heer had a very thoughtful observation that suggested the commonality with many/most of the writers on this site was not necessarily their opinions, but a kind of ahistorical, multi-media approach that encouraged or required a kind of cross-arts comparison. At the time I thought it was an interesting observation but mainly off base. But, seeing how many things you and I disagree about aesthetically, Noah, and seeing how heartily I agree with your comments above, a very clear distillation of your personal mission statement, I take it, I suppose he really could be right. Maybe that is the commonality between many of the diverse opinions here.

holly:

I put Hugo Pratt in my canon, but not _Corto Maltese_. I put Hugo Pratt in the canon because he drew _Ernie Pike_, written by the great Héctor Germán Oesterheld.

What you say is very interesting: it’s my original story.

Once upon a time little Domingos compared his fanboy taste in comics with his taste in literature and painting, etc… That’s when he understood one simple thing: he mostly liked great art, but in comics he liked junk. That’s when everything changed for him. The rest is history…

Sean, Is it a cross arts comparison or a cross time comparison, because the best contemporary comics are certainly comparable to the best of today’s film aren’t they? What about today’s pop music?

The canon when described at all doesn’t ever seem to include anything from a creator who is alive.

“everything in modern culture should be a fair target.”

But lots of people sneer at Watchmen on this site. Marguerite, James, and Jeet all have done so in comments I’m pretty sure….Domingos doesn’t like Peanuts all that much…like I said, Tarantino just got whaled on by a bunch of folks — those are three of my favorite pop culture creations/creators. Our Wire roundtable was mostly positive, but we had several pieces that were skeptical of one aspect of the show or another.. We don’t do a ton of writing on pop music, but when I write about it, I piss people off just as much as when I write about comics. I’m not sure what modern culture items you think are sacrosanct here? Like I said, different folks have different opinions. I don’t dictate what people can say, and in general if there’s someone who disagrees with me vociferously and eloquently in comments, my reaction is to try to get them to write for the site.

Maybe part of the problem is that you’re assuming that any comparison must work against modern culture? I don’t think that’s so…I like Peanuts more than Picasso or Cervantes, for example, and probably Tarantino more than those two as well. I don’t see the canon as a way to say, everything now is worse than everything then.

Sean, I’m interested in cross-arts approaches, and in theory critiques — but I’m not against historical approaches, and I’m not against people advocating for a comics centric focus either. That’s what Nate’s doing, basically. And, for that matter, Robert’s 10 best comics project was very comics focused (though of course comments went in various directions.)

I’m happy to have historical approaches and comics-centered approaches be part of the discussion. I don’t want them to be the whole discussion, though.

Well, in using “ahistorical” I thought I was using Jeet’s word, at least from memory. But what I meant wasn’t that there is no attention payed to placing a work in a historical context, but that rather the historical context is used to understand rather than to shield and insulate the work from criticism. It seems to me that this pretty characteristic of a lot of us–a willingness to compare works created in different contexts and cultures and times and analyze them for what they are or what they appear to be now rather than exclusively from the viewpoint of how they might have appeared in their original context.

Holly, people have different opinions about whether the best comics today are comparable to the best films or the best pop music. I in general think pop music is a lot healthier than contemporary comics…but that’s me. Different people have different takes. But those arguments do get aired here with some frequency. (Caro thinks contemporary comics are not anywhere near as accomplished as contemporary film, for example….or at least, I’m pretty sure that’s where she’s coming from.)

Noah, You said: “I like Peanuts more than Picasso or Cervantes, for example, and probably Tarantino more than those two as well.”

Thank you. That’s just what I was curious about. If you like Tarantino more than Picasso or Cervantes at least are clear as to where you are coming from.

Well, but I like Shakespeare more than any of those folks (Tarantino included.) I like Peanuts more than Tarantino too. Wallace Stevens more than Tarantino? Yes…but more than classic Metallica? Tricky.

It’s really a case by case thing for me…and will depend on the time of day and direction of the wind too….but like I said, canon formation isn’t something I’m super interested in for it’s own sake, even though it can be fun.

Noah:

You say that you don’t like Picasso much, but did you ever read him?

I’m referring to Picasso’s paintings…and I haven’t seen all of those either, of course!

I don’t hate him or anything, but he doesn’t really send me.

I meant his paintings too.

Ah, you’re arguing that his paintings should be read?

What piece(s) are you referring to in particular?

I agree with Noah when he says this “it just seems like comics has gone the consolidation/subculture route for so long (as Nate admits) that further progress along that road threatens to become sclerotic.”

I think the problem is exactly that: the public (I like the lit theory word “discourse community”) is SO well defined and SO specific that it actually determines not only the conversation about the art but the art itself, rather than the other way around. The comics-reading public is a thing independent from the comics it engages with, that most comics self-consciously and intentionally appeal to, rather than an epiphenomenon of neutral people’s discussion about those comics. Perhaps that epiphenomenon was what the OLD TCJ did, creating that community. But that community’s been stable, with a clear discourse and assumptions, for a pretty long time.

Noah also accurately states my position on the accomplishments of contemporary film. I think at least some of the reasons for that, though, have to do with the phenomenon Nate describes and how that worked in the early days of cinema. I think the emergence of a discourse community about film was much less about subcultural identity and much more about legitimating film in a multi-media, multi-form artistic context. Cocteau is the archetype of this, his friendships with Picasso and Gide and Proust and Diaghilev and Radiguet (et al., et al., et al.) created a sense of what art was and was for that informed his films, and his films informed our sense of what film is. As such (and he’s only one example), films’ original genetic diversity is much more diverse than comics. So even when film gets more self-referential in the mid-century, it’s referencing something more inherently diverse.

And you can argue that comics draws heavily from fine visual art, which in some instances is true, but the thing about film is that it was all arts, including writing, including music. (Cocteau wrote for Stravinsky…) Even today’s screenwriting takes writing and literature seriously in a way that comics does not, although it’s certainly never been as important for film as for theater, where dramatists and directors are still pretty separate functions. Still, I’ve never heard film people or theater people make the kinds of claims you hear all the time in comics, that the expectation of competent, nuanced writing as a baseline expectation for any professional work makes someone “anti-visual.” Maybe it’s because even though there are filmmakers and dramatists who only make films and plays, there are greats in those fields who considered themselves primarily writers: e.g., Beckett produced both drama and fiction, Cocteau wrote novels and poems. Auster writes screenplays and novels. And in all cases their literary work is exceptional and standard-setting. It seems like the only great in comics I’ve ever heard say anything really valuing writing is Saul Steinberg, and you never hear modern day critics acknowledge Steinberg’s own preferences in that area – his visual acumen is always what gets praised.

So I think it’s not just that comics is less genetically diverse, but that the discourse community likes it that way. Warren Craghead and Austin English, for example, don’t get all that much attention from the TCJ-defined community (although there was a recent interview!), so the “public” isn’t getting defined in ways that include their perspectives in our sense of what comics are.

Which is to say that I agree with Nate that comics have been about the formation of a public first and an art form second, if at all. But this is why I like the term “discourse community” so much — I think that it’s never a seamless, painless transition from the kind of discourse that supports a subculture to the kind of discourse necessary to support an artform. TCJ is in a unique position to encourage and support that transition, but they don’t appear to really deeply want to. Being at the top of the heap in the subculture is a hard position to do it from — it’s asking a big fish in a little pond to swim into the waters where they’ll be a small fish again. I get why they don’t risk their position and their influence within the existing industry for that goal. But comics has so much extraordinary potential as an art form, it makes me sad that the most influential critical voice in comics doesn’t see it as a primary part of their mission.

Picasso used visual metaphors a lot (_Guernica_ is a huge allegory. I remember being delighted in the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid reading them. Dalí did the same thing, by the way (maybe it’s a Spanish thing that began with Goya). Here’s a reading of his comic _Dream and Lie of Franco_ (_Songe et mensonge de Franco_): http://tinyurl.com/6z26vhf

“It seems like the only great in comics I’ve ever heard say anything really valuing writing”

Well, there’s Alan Moore. I think he’s great, anyway, and he certainly sees writing as important, and sees himself in relation to a broader artistic community than just comics, I think (he’s a performance artist, among other things.) But I get your general point.

I think Gary certainly saw part of tcj’s mission as connecting comics with other communities and making it part of the arts broadly defined, didn’t he? TCJ has always had a certain amount of writing on film…and of course, there was always Ken Smith writing about philosophy. It didn’t always quite work out (as Ken Smith shows) but it was certainly one of the things he was doing.

There’s a bit of that in the new tcj.com too; they had that long series on music by Kim Deitch, I know (which I have to admit I didn’t read.) And, to be fair, tcj.com under new auspices hasn’t been around that long; it’s been less than a year. Given how much of a mess the website was before, I can see trying to re-consolidate it’s position as an important critical voice before doing anything too odd.

I think Nate’s point that consolidation is important because of the huge shifts in the industry is interesting. That is, with the end of pamphlets and the threat to print in general, there’s a need for the audience to affirm it’s existence just so Jaime will continue making comics. It’s a pretty interesting argument…I’m sort of curious what Charles Hatfield would think of it, since his book talks a lot about the relationship between audience and production….

True on Moore – I should have said “historical” greats though. I wasn’t thinking about people who’re still really able to do work, but about the context in which the discourse community got formed (i.e., people comparable in influence over our ideas of the form to Cocteau in film). But it doesn’t make a meaningful difference. We could include Eddie Campbell and Austin, though, if the list includes people currently working.

I think the problem, though, that comics will ALWAYS face, or at least for a very long time, is that this type of thing is seen as “odd” rather than obvious and inevitable. The point about film is that it was never odd to see film as inextricably tied up with the other arts — that was the original position. I think it’s much, much harder to go from an intense, devoted medium-specifity to a multifacted one than it is to go the other way around, specifically because of the definitional limits of the medium-specific discourse community.

It’s also worth noting that if the audience wasn’t biased against other art forms, if they didn’t define themselves in relation to the medium itself (as opposed to, say, genres within the medium, as many fans of other media including film often do), then the relationship between the audience and production would be much different.

I recently read an article that I’ll try to find about a writing class Lynda Barry is teaching, and — at least from the presentation of the class in the article, which is perhaps not a trustworthy source — it sounded a lot more like a class in creativity or storytelling, than a class in “writing.” I think that’s part of it — there’s really not a deep sense in comics, even among the best writers, of what “writing” really means to writers. But filmmakers and dramatists really do tend to get it. I don’t know why that is — probably related to education.

What art forms are comparable to comics in this regard?

The thing that came to mind initially is video games.

A very strong case could be made that a large segment of comics readers who like things such as Feininger, Love and Rockets, Linda Barry, Frank King, Gary Panter, and so on, are far better informed about the great art of the past than are the general public. I wonder if contemporary taste doesn’t lag well behind what Domingos sees as the low standards of contemporary art.

Well…the general public is people who don’t really pay self-conscious attention to art at all, so that’s a really low bar.

Caro’s not talking about the great art of the past, though. The point is do comics see themselves as part of the great art of the present? That is, are they part of the arts broadly defined (including but not limited to the history of the arts?)

Here’s the Lynda Barry article: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/30/magazine/cartoonist-lynda-barry-will-make-you-believe-in-yourself.html

Compare it to this passage from Don Greiner’s wonderful book on the pedagogy of James Dickey:

Or, consider this essay by John Barth (in a rather spotty OCR from the original 1985 article: http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/06/21/specials/barth-writing.html

Barry’s course — which sounds wonderful in many ways — seems to correspond to the first item: the material. The article even says “Barry isn’t particularly interested in the writer’s craft.”

But if you look at Barth’s breakdown, the craft is what makes stories into writing. Craft includes “the rudiments of fiction.” And a good solid understanding of the rudiments of fiction is what seems to be missing from an awful lot of beautifully drawn comics I’ve seen (not to mention an even greater number of pedestrianly drawn comics I’ve seen.)

Screenwriters study the writer’s craft; screenplays are fiction. But art comics writers tend not to — and they’re especially dismissive of that last one, submitting apprentice work for critique. I heard someone on a panel at SPX say that one of the problems with working with a big press is that the editors tried to edit the comic but you can’t edit a comic the way you edit a book, telling the cartoonist that the joke fails here or whatever. That attitude isn’t a property of comics — it’s a property of an immature writer, because EVERY writer can learn from readers.

I guess all this rambling is to set up two questions – isn’t there something comparable to the “workshop” in studio art, where your peers critique the ideas and execution of your work? It seems like there would be, so I can’t imagine that person was getting that notion from visual art, but maybe I’m wrong.

And, if anybody reading this studied comics in a formal curriculum somewhere, what did your program teach you about writing? Was your experience more like what Barry goes for in her course, or what Dickey describes in his?

holly:

Huh? I really don’t have an opinion about contemporary art. I’ve been so detached of it for so long, I mean… However… from my limited point of view I can’t say that I like any contemporary artist. I can laugh with Maurizio Cattelan as much as the next guy or see the genius of Damian Hirst selling the golden calf to golden calf worshippers, but… that’s pretty much all… I like Liu Xiadong a lot though… Maybe you’re referring to my frequent allusion to a so-called dumbing down… It exists, I suppose, but there are other interesting things as well…

Noah:

Being part of the system Gary Groth is part of the problem, not part of the solution.

Caro:

I think that you gave too much credit to Jean Cocteau. Dada did a lot of films and so did German Expressionism. Even Cubo-Futurism produced Leger’s _Ballet Mécanique_ (let alone the Russians, of course). Film and modernism was a marriage made in heaven, it had to produce interesting things.

Domingos, I was trying to get at that with the parenthetical “(and he’s only one example)”… Not trying to say it’s Cocteau and nobody else, just that Cocteau fits the pattern I’m talking about. I do think he fits the pattern pretty archetypally though. Film was fortunate enough to be coming of age in a time when medium-specificity was less important than aesthetic philosophy for defining artistic communities, discursive or subcultural.

Noah/Holly – I agree with “including but not limited to the history of the arts”. But emphasis on “the arts” — music, painting, drama, literature, dance, etc. — not just the visual ones. I do think North American comics is pretty good at seeing itself as part of the bigger visual arts.

Lots of comics writers double as Hollywood screenwriters (at least aspirationally)…Grant Morrison and Mark Millar are 2 more….and Neil Gaiman, of course, is a novelist, short story writer, screenwriter, and comics scriptwriter. Maybe Hollywood movies (or TV shows) don’t count as “film”? I’m not sure this is really that valuable a criteria (multi-media/art) —though Morrison and Gaiman are, of course, more accomplished as comics writers than many of their mainstream brethren.

I do think Caro misleadingly configures the argument against being so “writer-centric”– The idea is more that the “story” can be told through the art solely in comics, so a command of “prose” is not really the important issue. (Manipulation of narrative and presentation of that narrative is still at issue, of course…but you don’t need ‘words’ to do it). I am a kind of word-centric guy myself, but it is obviously true that you can have a compelling and worthwhile comic with images alone. The fact that it is possible doesn’t mean it happens all that often though.

“I do think North American comics is pretty good at seeing itself as part of the bigger visual arts.”

Maybe…but there’s an awful lot of antipathy/resentment of contemporary visual art in comics, it seems to me.

Oh…and I don’t really think that the praise of Jaime’s work should rest on the interpretive community it initially found. I see that they may be proprietary about it…but I do think it stands up as “really good comics” regardless of those circumstances. Do I want to compare it Shakespeare—not really, but there’s not that much to compare to Shakespeare. It’s a different kind of pleasure and a different kind of reading experience. If it doesn’t float Domingos’ boat, that’s fine… but it does have its own value and pleasures, which are not completely detached from the “literary”–I’ve enumerated some of them in previous comments…

Domingos, Sorry, I took it as a given that you didn’t see contemporary art as near close to the equal of the past.

It’s kind of interesting that for quite a long time the “art scene” has been absent from public consciousness. Who was the last artist widely known by the public? Probably Warhol.

Eric, I think when I said “the craft is what makes stories into writing,” I really should have said “the craft is what makes raw ideas into stories.”

The story can be told through the art, but — as I’m sure you know — the story is still “written.” It isn’t just drawn. That’s the point of the distinction between medium and craft that Barth draws, and it’s a point that people in comics often try to elide. The craft of fiction is separate from the craft of prose-smithing. If the comic makes semiotic sense, if it’s a narrative, it does not matter at all whether that narrative is told through pictures or in words — Barth’s notion of “craft” still applies.

Also, just because you don’t need words to do it doesn’t mean that people who have done it with words have nothing to teach you. There is an understandable paucity of really powerful examples of “manipulation of narrative and presentation of that narrative” in purely visual arts, especially sustained narrative. Like Dickey, I think that studying examples are important (and I’m sure you do too, or you wouldn’t teach literature…) But there are lots of examples of great sustained narratives in prose. People who have done it with words, therefore, are probably the best teachers available to cartoonists, because you have a huge diversity of approaches and techniques for manipulating narrative available to serve for inspiration and ideas. (And honestly, even film almost always does it with words too.)

But it’s not just pedagogical — being in conversation with the ways writers and screenwriters “manipulate narrative” is one of the ways you make the artform about “the larger field of the arts.”

The fact that comics CAN participate in those conversations is that potential I mentioned earlier. The fact that comics often DOES NOT I think is much more closely connected to the attitude within comics toward words than you’re allowing for.

No I agree with you about virtually everything here…It’s just the way you set up the counterargument seemed a bit of the “straw person” to me. I’m a bit more forgiving of contemporary comics than you are, I guess…but in general I wouldn’t disagree.

Isn’t Banksy pretty widely known, Holly? Maybe he’s not really part of the contemporary art scene…

Yeah, you just workshopped my comment, Eric. ;).

It’s not really that I’m not forgiving of them — I enjoy a lot of contemporary comics and I think there’s some really interesting stuff happening visually. I would just really like to ALSO have more comics where it was really obvious that the people making them were avid and voracious prose readers.

Also, it’s just kind of a pet peeve. I’m still reeling a little from that panel and the notion that comics can’t be edited (in the sense that they are not subject to workshop-style critiques.)

WTF?

Having sat in on Lynda Barry’s writing class and lectures, I’ll simply say that 1)Barry is by far the single most talented teacher I’ve ever seen in my life (and I’m someone who has attended all sorts of classes at all sorts of schools) and 2) it is false (or rather simplistic and misleading) to say that Barry isn’t interested in craft.

In sum, this discussion seems alarmingly divorced in the actual history of comics or knowledge of the production process behind comics.

Barry’s primary interest, as I see it, is the psychology of creativity, in getting people to tap into the the playful roots the nourish our ability to make things. But once Barry helps students open themselves up to their creativity, she does also advise them on editing and refining their work.

Of course, Barry’s pedagogy is unorthodox, but that’s what makes it valuable (and it’s of great value, I would add, not just for cartoonists but for creative writers of all sorts, including writers of non-fiction).

I’m not so sure, either, that comics can’t be edited or are resistant to the more traditional workshop approach. I’ll simply note that the Center for Cartoon Studies in Vermont is modeled fairly explicitly on the classic creative writing program of the type found at University of Iowa and elsewhere.

Mainstream comics have always been heavily edited, so much so that Jim Shooter once argued that the editors were the real creators. In the alternative comics world there is some resistant (partially because of the heavy-handed editing in mainstream comics) to editing, but even here Spiegelman and Mouly have been very important hands-on editors.

Caro sez: I’ve never heard film people or theater people make the kinds of claims you hear all the time in comics, that the expectation of competent, nuanced writing as a baseline expectation for any professional work makes someone “anti-visual.”

Maybe not among practitioners, but that attitude is quite prevalent in auteurist film criticism. That species of criticism is virtually defined by it. Truffaut and Godard certainly broadsided work they felt was too literary in style. Andrew Sarris was known for upbraiding peers that he felt were overly literary-minded and not sufficiently visual-minded in their criticism. Richard Brody dumps on Pauline Kael’s work on that basis almost every other week in his blog at The New Yorker‘s website.

That attitude is, I think, really typical of fanboyism in both comics and movies. They focus on the visuals because it doesn’t really demand them having to know about anything outside of comics or movies. They aren’t generally interested in work from other fields unless they can somehow relate it back to their medium of interest, and that’s usually by trying to claim the outside work for their preferred medium in some manner.

One more thing re. Picasso:

He didn’t use visual metaphors much in _Dream and Lie…_, but this is a good example: the eyes/boats link salty tears to salty water; the tree/hand is the tree of Guernica (the Gernikako Arbola is an oak tree under which the main ruler of the land made the oath of respecting Basque’s liberties).

I agree with Jeet (what a first!), but I continue to think that he could avoid unnecessary remarks like this one: ” this discussion seems alarmingly divorced in the actual history of comics or knowledge of the production process behind comics.”): Lynda Barry is one of the best writers in comics and I don’t believe (but I really don’t know) that she doesn’t pay attention to the craft of writing. (In case you don’t know she wrote and drew _What It Is_, but I never read it, so, I don’t have an opinion.)

“Barry’s primary interest, as I see it, is the psychology of creativity, in getting people to tap into the the playful roots the nourish our ability to make things.”

I have to say, as an approach to creativity, this makes me gag. But that doesn’t mean Barry’s a bad teacher, of course.

Oh, and I’d never seen that Picasso, Domingos. It is pretty great.

Picasso did dozens of preparatory drawings for _Guernica_. He was in creative turmoil at the time. A giant like that in creative turmoil is something to reckon with. I must confess that I just read one book about Picasso in all my life, but searching the www I didn’t find much about Picasso and visual metaphors which is quite surprising. This should be a primary focus for Picasso scholars out there. If someone knows of a book on the subject I would be glad to know about it.

Comparing Lynda Barry to Julia Cameron? How very boorish of you. In Barry’s defence it must be said that her approach has nothing to do with self-help (at least on the evidence of What It Is).

“How very boorish of you.”

I’m reading this massive biography of Khruschev at the moment. It may have rubbed off.

Well then a “shoe banging-smiley” would have been in order…

I’m not sure what the point of bringing up Julia Cameron is — if you disagree with Barry’s pedagogy, then the thing to do is criticize things Barry actually says or talks about either in her lectures or in her books (What It Is and Picture This both grow out of her teaching). As Suat rightly notes, Barry isn’t talking about self-help. I understand that words like “creativity” have a new-agey feel and that’s unfortunate. But Barry isn’t at all new age-y; she’s talking about the actually psychology that goes into making things.

Well, “the playful roots that nourish our ability to make things” is a phrase that Julia Cameron could have written, and the bits and pieces of press I’ve seen about Barry’s teaching also sounded more like Cameron than I was altogether comfortable with. But I’m happy to take your word for it that that’s not what Barry’s doing.

Jeet, the comment about Barry not being interested in craft was on the first page of the NYT article on her class; it’s not an assertion I’m making about her work.

Perhaps the NYT writer misunderstood her, but I think it should be pretty easy to see how the description of the techniques and approach she uses appear significantly different from the kind of teaching one got from Professor Dickey (whose workshop _I_ took, as well as Dr Greiner’s — Greiner was the one, Noah, who made me read “The Sound and the Fury,” darn him!).

My criticism of teaching the psychology of creativity is this — that psychology, more than any other kind, isn’t the same for everybody. And an awful lot of literary creativity has tended to emerge out of the mindset of an advanced critical reader, not some playful wellspring of creative openness. There’s nothing wrong with that kind of “readerly” creativity. You see that in Dickey; you see it in Barth.

I don’t, however, see that in Barry’s pedagogy, which is why I said her teaching was about something different. And so I think you’re missing the point of the comment, which is not whether she is a good teacher, but whether there is a difference in discourse community there, and whether it can and should be bridged. Are you suggesting that Barry’s pedagogy is, in fact, within the discourse community of traditional creative writing? From the quotes in the article, it seems like Barry herself is resistant to that.

I don’t DISAGREE with Barry’s pedagogy, and certainly not for her goals, which it seems to fit well. I do think Barry’s pedagogy isn’t a substitute for Dickey’s pedagogy, and that a great writer probably needs some of both kinds.

Do you think Barry’s is a substitute, or do you think there’s value in both? Because the only thing that I DO disagree with is what sounds like her contempt for the more traditional pedagogy that writers like Dickey practiced. It works just like her comment on Franzen.

One of the wonderful things about Mr Dickey was that he could take a student from the backwater of South Carolina who’d never read anything but the Bible and the newspaper and make him understand why TS Eliot was poetry. And he didn’t do it through “inspiring their creativity;” he did it, as the excerpt I quoted says, through sharing his love of reading and through the idea that reading is a source of inspiration for creativity. Sometimes he turned those people into teachers and writers themselves — but he always turned them into readers.

Disrespecting that isn’t cool at all. Pedagogy doesn’t have to be “about” psychology to be effective psychologically.

Robert, I’m not a big fan of Truffaut…I wouldn’t take Godard so seriously on that, though. Maybe literary tenses lol, but Breathless is littered with actual quotations from literature, including Faulkner. The influence on his films (and his own affection for in his writing) of Baudelaire and Appollinaire and Brecht I think is indisputable. He was a supporter of Marguerite Duras, and she was an influence on him. If Baudelaire and Brecht and Duras aren’t literary, what is?

But that the attitude exists in film fanboys too doesn’t surprise me a bit. It’s an easy cop out for any medium. I’ve been lucky not to encounter it there, I suppose.

That comment was sloppily written. It misrepresents my view of Truffaut and Godard. I’m pretty astonished by some of what they raved about, but the stuff they were knocking often had it coming to a good degree, such as René Clément films and the stuff Marcel Carné did outside of his work with Jacques Prévert. They were both pretty erudite and curious about things outside of film–Godard especially. The “fanboy” label belongs more to Sarris and the critics who followed in his wake. Brody is a prime example.

Yeah, I agree — not that your comment was sloppy! But yes, it seems like what auteurism was intended to be in the beginning and what it became in the hands of the fans and acolytes were really at odds. It wasn’t meant to be a cult of film at the expense of everything else (although I agree it’s much more that in Truffaut’s hands than Godard’s.)

The New York Times article was very good but it missed a few nuances of Barry’s teaching — it’s kind of hard to describe everything that goes on in her classroom. I think Barry’s emphasis on psychology is salutary because the act of creation is, ultimately, an intimately personal one. The more traditional emphasis on technique in creative writing programs also has value but it runs the risk, in my experience, of encouraging a kind of facile skillfulness at the expense of passion and engagement.

In any case, there is room for lots of different teaching styles. And I’d add that when it comes to comics, the major tradition has been skills and crafts oriented teaching — think of the mail-order cartoon schools (like the ones that Schulz studied at) or Hogarth at SVA or the Kubert school.

I don’t know much about Dickey as a teacher, but I always thought he was pretty cool. He was primarily a poet, but he wrote fiction, too. Deliverance was one of my favorite novels growing up, and despite it being “masculinist” to the core, it still seems to be held in very high regard. He was also heavily involved with the movie adaptation. He wrote the screenplay and also gave a really good performance as the sheriff in the closing scenes. (The movie is pretty good all around.) To successfully spread yourself around like that is something I really admire.

“And an awful lot of literary creativity has tended to emerge out of the mindset of an advanced critical reader, not some playful wellspring of creative openness.”

This is a nice explanation of why Cameron is kind of the devil. Thinking and intelligence and knowing a ton about the art form you’re working in are not barriers to creating good art.

I also feel like maybe the people saying Barry isn’t like Cameron haven’t read Cameron? Not that anyone should read Cameron; nobody should read Cameron. She’s hideous. But, on the other hand, it’s good to recognize the face of the enemy, I guess.

Be that as it may…that New York Times article could be about Cameron. Stuff like this:

Or this:

That’s totally Cameron territory. Lack of creativity as something that needs to be healed; getting back to natural writing of children.

Or the fear of criticism:

Or art as therapy:

I actually think a lot of writing by kids is amazing…but writing by kids doesn’t sound anything like the stuff the NYT talks about the writers doing in that class. Writing by kids is bizarre and filled with random pop culture references and repetitions and leaps of logic. It’s not great because it’s natural; it’s great because they haven’t figured out how the genres and memes are supposed to fit together, and as a result you get this all over the place mess that can be really fun (or sometimes really tedious, too, is the truth.) But…the best way to write like a child is to listen to lots of kids’ stories. It’s to read (or listen) a lot, not to forget what you know and feel backward or some such rot.

I dunno…academic creative writing classes can be problematic too in a lot of ways, and god knows contemporary academic fiction has crawled into a hole and died, and contemporary poetry is even worse. But does it have to be the Iowa Writers’ Workshop or Julia Cameron? Better no one should write anything ever again at that point.

Jeet, I agree with you about the Program; I can’t remember if you were in on it but we had a thread here awhile back that made similar points, about Elif Batuman’s critique of the Program in the London Review of Books. I think she’s consistently spot on.

But there need to be other alternatives to the Program besides, to borrow the words of Truman Capote, “sensitive, intensely felt, promising prose,” and especially sensitive, intensely felt, autobiographical prose. There’s a very necessary article in The Atlantic’s fiction issue called “Don’t Write What You Know.” But listen to our treasure-teachers — Dickey, Barth, but the best example is Kermode — and it’s clear that great literary writing is about literary reading. And literary reading isn’t always really that intimate. It’s very interlocutory.

So I think it’s important that people who write comics, ambitious ones, at least, think about writing and reading in terms beyond just Barry’s or the Program — because writing has a history too, and one that isn’t coterminus with comics texts. I think Dickey’s very readerly approach is a wonderful and fecund approach. It’s very social, very interactive, and not in the least self-important or even particularly self-interested, which is why I think it was so easy for him, as Robert points out, to move between fiction writing and screenwriting. I think anybody who wants to write fiction stories — in any medium — should read that book I linked to above.

But I don’t want to whitewash him — I absolutely don’t think he would have bought into Barry’s notion that anybody can be a writer. I think he thought it was an incredibly difficult thing to be and that it took an immense amount of dedication and study and work. Even in master classes he was more challenging than encouraging. But that challenge — oh, how he made it shine!

It was something I found inspirational as a teacher — I always made sure there were at least a few texts on my students’ reading lists that were much too hard for them, and consistently my students listed those lessons on evaluations as their favorites. I just don’t think raising the bar ever does lasting harm.

“the act of creation is, ultimately, an intimately personal one”

No it’s not. You make art, you’re communicating. You’re using language or images that take on their meaning in a cultural context. It’s personal in part, but it’s always personal in a relationship with others.

There is no creativity outside of craft, either. Creativity only exists in the context of specific forms, just like meaning only exists in the context of specific forms. Art’s the human bit, and what’s human is social. If you want natural creativity, piss in the grass and grunt like an ape. If you want to make art, you have to think about it.

For what it’s worth, Noah, Drawn and Quarterly makes the comparison with Cameron in the press for Barry’s book:

http://www.drawnandquarterly.com/newsList.php?item=a492daaf1032b4

That’s what they call a smoking gun.

Although actually, D&Q included it in their press section, but the comparison was actually penned by The Globe and Mail.

Still, not a random comparison. Google their names together and you get a lot of hits for people putting them on booklists and citing them as similar authors. I think it’s mostly that people who like Cameron also pretty consistently like Barry’s book. Probably doesn’t work the other way around.

The horror! The horror! We should never have doubted you, Noah…I hate self-help books.

Also, I’m not terribly convinced by that Atlantic article (“Don’t Write What You Know”). For one, he’s still writing from experience according to the details of his piece. And isn’t the disease he’s describing quite specifically American (or maybe attributable to best selling English literature)? I don’t see it much in a lot of the top continental Europeans. Further, haven’t SF writers been doing this kind of thing for decades? You mean lit fic took this long to catch up? If I were to give a more down to earth analogy, it sounds a bit like the articles about amateur photography which pop up now and then all over the web. Things like “You should only use Manual mode” or “Professionals use Aperture mode”. The answer to these kinds of articles is a simple “you should do whatever works”.

Link to the Globe and Mail Lynda Barry article (where she is compared to Julia Cameron).

The European v. American point is in Batuman’s essay, isn’t it? It’s DEFINITELY an American problem; the Program hasn’t infected the Continent or the Commonwealth, as far as I know.

But “write what you know” is very much a trite catchphrase used to excuse all kinds of horrific drivel; I think it’s from Rilke, which every self-important wannabe writer inhales like crack cocaine, and although it’s definitely not a problem with top writers anywhere, America or otherwise, it’s absolutely a problem with amateur writers (like the ones who tend to read the Atlantic fiction issue, and probably the ones who take Lynda Barry’s classes…although Lynda Barry is surely better than Rilke.)

I think it’s also a problem among the current generation of Program-trained writers who are steeped in indie culture with its cult of authenticity. The Program isn’t free of it (as you can see in the continued use of experience that you point out) and the Atlantic article I think is a necessary reminder with those audiences in mind not to let it get out of hand. But it’s absolutely insufficient — the approach of Kermode et al. moves out of experience altogether and I think is much preferred.

“The European v. American point is in Batuman’s essay, isn’t it?”

Oops. Is it? Must have missed it when I skimmed the article.

“I think it’s from Rilke, which every self-important wannabe writer inhales like crack cocaine”

Ok, this made me LOL.

You all have inspired me; I’m going to reprint an essay about my childhood tomorrow, I think.

Here’s a blog by a schoolteacher who uses Cameron, Rilke and Barry in her teaching, among others: http://finneyfrock.wordpress.com/2011/04/05/creativity-as-a-bold-and-sometimes-scary-act-in-the-classroom/

A class or two from that type of approach is never a bad thing. But that is the ONLY kind of writing instruction the vast majority of my students had received by the time they got to college. A little bit of it mixed in with other things would have been fine, but I had students who had been in writing classes exactly like that year after year from 5th grade on, and they wrote grammatically incorrect and disorganized prose, and after all that instruction they still weren’t capable of being creative in the sense that academic work requires, that readerly, interlocutory sense. What they were was expressive, which is not the same thing as creative.

I can’t tell you how destructive that “there is no way to do this wrong” attitude is for students in college. It hurts them terribly on the SAT. It hurts their grades. It diminishes the tools at their disposal to solve problems in their understanding of things they’ve read. There IS a wrong way to write a collegiate-level essay, and the only way they know to write is this nebulous, “creative” one, and they get marked down, and then they lose all faith in that teacher who taught them this inspirational way of writing and they doubt their creativity and abilities even MORE. And what are you supposed to do when your choice is to let them graduate from college without being able to write a properly punctuated complex sentence or an argumentative essay or even a professional cover letter for their resume, or destroy their confidence because it’s built on such shifting sands?

It’s a horrible, horrible way to teach writing, UNLESS it is paired with study of the medium and craft as well, as Barth points out. Barry’s teaching adults, it looks like, so whatever. But schoolchildren need grammar and essay skills too. This stuff is too seductive by half, especially since it’s a hell of a lot easier to teach than diagramming sentences and parsing Shakespeare.

I think Lynda Barry’s reputation can stand my disparaging her on this issue a little bit, really. And she really does appear to be teaching primarily adults who are often completely blocked and do not write at all, and in that context this pedagogy is very appropriate. But for training real, serious, professional writers (like cartoonists who do their own writing should be)? It’s really only just a starting place.

“There IS a wrong way to write a collegiate-level essay”

Having marked undergraduate philosophy papers, I’d say there’s more than one wrong way…

“Love & Rockets is no longer part of a larger community of comic readers. It comes out as a book now, and not in a monthly pamphlet. This isolates its public from the institutional frameworks that incubated it. Similarly, with the end of TCJ’s regular publication in print, and the balkanized world of online criticism, consensus about what comics are worth reading, what comics criticism should look like, etc. The public constituted by Love & Rockets is understandably nervous.”

This is highly dubious. Considering how far one has to drive to find a comic book shop that has anything but the usual junk…. Depends how one defines “public” and “community,” I guess.

“Caro – The point about film is that it was never odd to see film as inextricably tied up with the other arts — that was the original position.”

It depends. Yes, it was tied up with other arts, but it wasn’t held to the same esteem as them. And for a very long time.

“I think it’s much, much harder to go from an intense, devoted medium-specifity to a multifacted one than it is to go the other way around, specifically because of the definitional limits of the medium-specific discourse community.”

Part of that specificity may be due to the nature of the medium. Film needs composers, actors, screenwriters, etc. Comics is just one person in his room. Let’s not forget the economics factors. Historically film has been a way for writers, artists and musicians to make a quick buck.

“eric b- I do think Caro misleadingly configures the argument against being so “writer-centric”– The idea is more that the “story” can be told through the art solely in comics, so a command of “prose” is not really the important issue. (Manipulation of narrative and presentation of that narrative is still at issue, of course…but you don’t need ‘words’ to do it). I am a kind of word-centric guy myself, but it is obviously true that you can have a compelling and worthwhile comic with images alone. The fact that it is possible doesn’t mean it happens all that often though.”

Right. The issue isn’t necessarily a lack of sensitivity to prose, although that can be part of the problem. It’s a lack of rigor. The thing with comics, though, is like with film- it’s very hard to find someone who is equally adept with words and images. And with comics, I think that problem will always be naturally compounded. One could argue that it’s harder to create a comics masterpiece than a masterpiece in any other art form.

“Jeet Heer – I’m not so sure, either, that comics can’t be edited or are resistant to the more traditional workshop approach.”

Once again, the New Yorker and manga models come to mind. Both as you all know have strong editorial infrastructures.

“Noah B- Maybe…but there’s an awful lot of antipathy/resentment of contemporary visual art in comics, it seems to me.”

I’m reminded of a Kenneth Smith quote from an old issue of TCJ. To paraphrase, “Abstraction is the enemy.” But I don’t think this is at all an unusual position anywhere outside the high art world.

Steven, everybody loves abstraction; I’m pretty sure comics people aren’t upset with Jackson Pollock. The thing people hate is conceptual art.

Caro, I’ve only read his Rilke’s poetry and the novel, which are both amazing, and extremely well-crafted. But I can believe his Letter to a Young Poet is problematic. You can’t trust the romantics.

I actually wrote a comp and grammar book for high school students. I tried to do more or less what Caro suggests, I think — that is, provide a lot of models, talk about what the models were doing and how, and then encourage students to use that in their own writing. You also want to create writing prompts that are interesting and enjoyable, too, obviously…but I think it’s easier to create meaningful writing prompts if you’re also having students read and read critically (“reading critically” here meaning for high school freshman something as simple as, “this is descriptive writing” “this is a complex sentence”…)

Steven,

I’m not sure what you’re getting at, given that your comment about the lack of shops seems to support what I was saying. My point, and I’m sorry it wasn’t clearer, was simply that the infrastructures that brought together different publics or communities of readers (by which I mean fans pledging allegiance to a certain idea of good comics books or another)are disappearing, and new networks are springing up in their place. Better comics shops were one of those infrastructures, but they’re going the way of the dodo.

Noah…having read “What It Is”–I can guarantee you would hate it (In fact, I was thinking that while I was reading it). It does, in fact, come off as new-agey, and self-helpey. Anyone with a moderate degree of cynicism should stay away. I hadn’t read much of Barry’s work previously—and it pretty much turned me off to her….which isn’t to say some of her other stuff might not be far superior—just that I, perhaps, chose the wrong thing to start with.

Steven – there’s no reason art comics has to be a single creator, anymore than film does. If you can’t write, collaborate. If you won’t collaborate, study writing. The “let the writing go to shit in the interest of having complete control over every piece of your work” is selfish narcissistic wankery that also happens to be shockingly unprofessional.

And that, Eric, is what bothers me about “self-help”, especially for writing. Writing is a profession. Good writers study it, they work at it, they treat it as a job and they are ambitious and disciplined. Workshop is about learning how to get your head out of your ass and how to leave your ego in your locker. It’s about growing up and moving past the apprentice stage.

There can be and will always be a ton of DIY cartooning, just like there’s DIY art and DIY fiction. And it’s great that comics has so many amateur creators who love the form and love creating comics.

But if comics is to be taken seriously as an art form, the form also needs to produce some professionals. And being a professional artist is not sufficient to be a professional comic book creator – you either need to be BOTH a professional artist AND a professional writer, or you need to collaborate. Otherwise you’re letting the superhero factories define what professional work in cartooning looks like, and that hurts everybody.

That said, I think Lynda Barry herself is relatively professional, although she does not appear to be interested in participating in the formal discourse community of creative writing. As Suat said, she’s a very talented writer — she’s sort of comics’ equivalent of Woody Allen, without the creepy. That is, really funny personal essays with a psychological self-examination bent. She’s a little more personal than Allen and a little less conventionally “witty”, but equally funny. (She’s no Nabokov, but she’s not trying to be…)

“What It Is” is absolutely, categorically the wrong place to start with Lynda Barry. In fact, it’s nothing like her prior work which is about childhood insecurities among other things. The Woody Allen without the creepiness comparison is pretty good. Noah will still hate her earlier work but for different reasons I imagine.

The reason I took issue with the Cameron comparison is because here (as so often before) Noah is commenting on a cartoonist whose work he’s only marginally familiar with. If you want to critique Barry’s teaching, then the best thing to do is to read her books or attend her lectures. What you shouldn’t do is bring up a book written by someone else that you don’t like. Since you haven’t read Barry or attended her lectures, you’re not in a position to say whether she’s like Cameron or not, or to what degree her thinking overlaps with Cameron. It’s a very simple point. The nice thing about criticism is that it is very democratic. Any idiot can be a critic: all you have to do is read a book or watch a movie. But having said that, it is very bad form in a critic to constantly make comments on books and artworks that he or she hasn’t actually spent time with (or has spent a minimal time with).

Eric: I really didn’t like What It Is, but I’d highly recommend One Hundred Demons.

Caro sez:there’s no reason art comics has to be a single creator, anymore than film does. If you can’t write, collaborate. If you won’t collaborate, study writing. The “let the writing go to shit in the interest of having complete control over every piece of your work” is selfish narcissistic wankery that also happens to be shockingly unprofessional.

Well, there’s a mystical difference between collaborative and single-creator comics that’s perceptible only to those in the know. It’s why single-creator comics are inherently superior to collaborative comics. So says Gary Groth and all respectable art-comics creators and the current tcj.com regime and their fellow travelers and basically anybody who deserves to be taken seriously.

Sorry, Caro, but you can’t say things like that and be allowed into the club.

Hey Jeet. So…you were saying it wasn’t like Julia Cameron not because it wasn’t like Julia Cameron, but because it’s wrong for me to mention Julia Cameron because I haven’t read Lynda Barry? I get it; it isn’t whether something is true or not, it’s whether the person speaking is properly credentialed. That’s an interesting approach to criticism I guess.

So when the Globe and Mail and D&Q say it’s like Julia Cameron, is that okay then?

In any case, I was making a fairly minimal claim, I thought. Which was that the bits about Lynda Barry’s pedagogy I had read (including now her discussion of her work in the NYT article) sounds an awful lot like Julia Cameron. Whose work I am actually quite familiar with; I’ve read the Artist’s Way multiple times, and I believe I’ve read her second book as well (it was a while ago; they tend to blend into one nightmarish bolus). I presume you have studied Cameron closely also since you categorically denied (in the face of D&Q’s blurb) that Barry is anything like Julia Cameron.

This seems to be a constant source of confusion for you, so perhaps I should state it more clearly. On my blog, I intend to comment on whatever strikes my fancy. I’m happy to say what I have read and what I haven’t, but just because I’ve read a small amount of someone’s work is not going to stop me from saying, “I have read a small amount of this person’s work, and what I have read strikes me in this fashion.” The insistence that only experts (those who have read her book? who have attended her sessions? who have read all of her work and attended her sessions and written for the Globe and Mail?) may speak is the opposite of democratic. I have less than no interest in your definition of what is and is not good form in criticism. I don’t want to be in your club. I don’t want to get a little certificate making me a bona fide comics critic who can gush about the canon in the prescribed fashion.

Having said that, your perspective is always, of course, as welcome as anyone else’s here. I’m even happy to have you opine on Julia Cameron, whether you have read her work as closely as I have or not.

Jeet, do you find yourself at every Jennifer Aniston movie wishing that you hadn’t waste your money once again?

Caro, what about someone like John Porcellino, would you say that he let his art go to shit for narcissistic wankery?

Charles – I didn’t say anything about anybody’s art going to shit. I said writing. Is that a telling Freudian slip on your part? It sort of proves my point if it is…

Robert – I’m ok with being out of that club. Those folks aren’t in my club either, the one where Feuchtenberger and deVries get pride of place at the top of the canon.

But then there’s Domingos’ often-gone-to reference of Oesterheld, who should pass muster with that crowd, and who consistently collaborated. Obsessive auteurism has the same problems in comics that it has in film.

No, I’m wondering if you only care about the writing going to shit, but not the art. It seems to me that you could take the same position about the art as you do about the writing, but perhaps people such as yourself are more reluctant to make that claim.

In case that’s still not clear: would you say to someone like Porcellino, “If you can’t draw, collaborate. If you won’t collaborate, study drawing”?

Oh ok. No, I’m not a big fan of punk DIY stuff in any aspect (writing, art, music) if that’s what you’re asking, and yes, someone could take that position.

But it’s not a battle I’m interested in fighting. I’ll just buy things with art I like.

I don’t think the problem is entirely with the DIY aesthetic, because there are people who clearly aren’t into the DIY aesthetic with regards to their drawing. The problem I face pretty consistently is that art/alt comics with extremely professional, often extraordinary art that I like a lot quite often have journeyman/pedestrian-to-bad writing. It’s really, really hard to find comics with extremely professional, extraordinary writing regardless of the art. Problems with writing seem to me much bigger and more pervasive overall than just an epiphenomon of a generalized taste for DIY.

A lot of those really talented and dedicated and skilled and professional artists don’t really seem to understand that writing is every bit as much work as drawing or that you need to have read a whole hell of a lot to do it well. Those artists are the ones I’m concerned about — the ones who obviously value quality and professionalism but miss what that means for writing.

I heard this statistic once — a good fiction writer has probably read something on the order of 5,000 fiction books by the time she is able to produce apprentice-level prose, and a great fiction writer will have read upwards of 10,000 (it’s related to that “to be good at something you have to have done it for 25,000 hours” stat).

Those stats are probably garbage in any empirical sense, but there’s a kernel there that has to do with discourse community, with knowing what it is that voracious readers are used to seeing and will look for. What cartoonists do you think have read 10,000 works of prose fiction?

Do single issues of The Avengers count?

I’m not so sure that I’d characterize art comics as being more concerned with the art over the writing (that was Image’s basic founding motto). Whatever one might say of the writing, I’d say it’s probably of a higher caliber than the art. This was the “wish it into the cornfield, Jimmy” Kochalka debate back in TCJ’s letter column. There are plenty of art comics enthusiasts who eschew craft. I’m doubtful the writing suffers more than the art for that reason.

Caro–

I’m with you. I just wish someone would publish W the Whore in English so I could sit down with it. Neaud’s Journal, too.

Oh, and Oesterheld. In fairness to the hipster-fanboy crowd, I don’t think anything by him has been published in English yet, either. They might change their tune about collaboration then. I doubt it, though. They’ve gone to so much trouble to create their litmus tests and secret passwords. I doubt they’ll give up on those any time soon.

Anyway, 10,000 works of prose fiction? At a book a day, that would take you 27.39 years! Who reads that fast?

W the Whore is still available in English from Bries. 11.50 Euros.

Charles – When I was in high school I read an average of 10 books a week and significantly more during the summers (on the order of 3 a day). About half of them were SF or romance and about half of which were “classics.” I read my first full-length non-children’s book in the 4th grade and kept up that pace pretty consistently from then until I went to college. My husband read about 12 (he didn’t have piano lessons and dance to cut into his reading time), but I don’t know what the breakdown was. I’m a very fast reader – I read Midnight’s Children on one pretty long Saturday. I don’t like to put a book down once I pick it up and most books take me between 2-3 hours to read. I don’t think that’s particularly unusual among people who turn out to be writers, actually. I had colleagues in graduate school who read faster than me and kept up an average of 3-4 books a day.

I offer the stat, though, not so much as a real numeric measure as to point out that literature has a kind of “litmus test” too. You can kind of tell when other people have that experience, that much intuition about what happens in prose. That’s what I mean by a discourse community.

And it’s not that I think EVERY comic ought to reference that discourse community. It’s that I think comics still need to figure out what it means to reference that discourse community.

You brought up DIY and music is a good comparison. There is plenty of simple, intensely felt and authentic/sincere punk and blues. But there’s are also genres where simplicity and intense feeling aren’t all that important — from complex electronica or anything with impressive instrumentals to classical and jazz. Music doesn’t pander to the tastes of a single subculture; there is music for every subculture. That’s where comics needs to get before it can be a “medium” instead of a genre.

And there’s been headway in the visual space, but less headway in the narrative.

Domingos, maybe you should write some translations of Oesterheld to help English speakers who want to just buy the originals already.

Charles, to your first comment — technically, Ginsberg eschewed craft too. But you can still tell he’d read a hell of a lot of books…

That’s why I think training or education or “the rules” or whatever isn’t really the point – the point is the discourse community. I think Nate’s article gets at that; I just think he isn’t attentive enough to the ways in which discourse communities precede specific works rather than forming in response to them.

I’m amazed by that, Caro: the average American adult reads at about 300 wpm. The average minimum amount of words in an SF novel is about 80,000 words. That means the average reading time for an SF novel is about 4 1/2 hours.

Sorry for disrupting the discussion, but a champion-level speed reader (minimum of 1,000 wpm) can read that SF novel in about 1 1/2 hours.

It cheered me up when I read Sartre’s complaint that he was a slow reader.

Huh, I never thought to try and figure out how fast I read. Let’s see — I just re-read Northanger Abbey in a little under 2 hours. Google says it has 77000 words in it. That’s about 700 wpm.

That’s not too anomalous for that average, considering that there are surely far more slow readers than fast readers.

Reading fast just makes it easier to get a lot of books under your belt, though; it doesn’t have anything to do with being a good writer. I know there are some famous writers who were very slow readers, maybe Melville? They say Yeats and Fitzgerald were dyslexic, so nothing is a formula. (Yeats’ father read aloud to him extensively throughout his youth because Yeats couldn’t, which is obviously slower, but nonetheless effective, and probably gave him a better ear than reading voraciously but silently would have…)

Robert: As I understand it Ego Comme X are doing some kind of English version of Neaud’s journals. (I can no longer find my source for that.)

Caro–