Jaime Hernandez’s “Browntown” has been lauded by everyone from Tom Spurgeon to Jeet Heer, the later of whom states that it is “arguably one of the best comics stories ever”.

It’s a bit of a let-down, then, to actually read the thing and discover a decent but by no means revelatory, piece of program fiction. All the hallmarks are there: the precocious child narrator as guarantor of authenticity; the ethnic milieu as guarantor of authenticity; the sordidness as guarantor of authenticity and the trauma as guarantor of authenticity. Poignant ironies fall upon the narrative with a sodden regularity, till the only landscape that can be seen is the wet, heavy drifts of meaning.

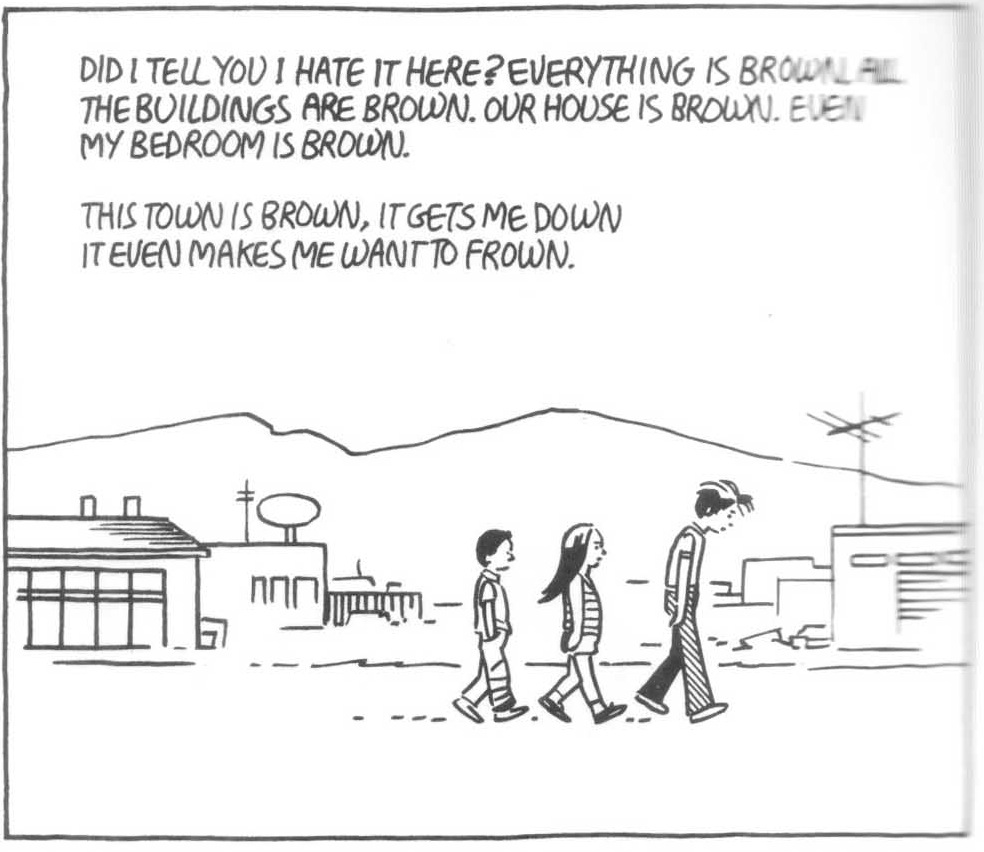

For what it is, “Browntown” isn’t terrible. Jaime’s precocious child narrator is endearing

his ethnic milieu is surprisingly uninsistent and unforced; his traumas are doled out with a disarming lightness — as when Calvin’s years of abuse are limned in the space between panels:

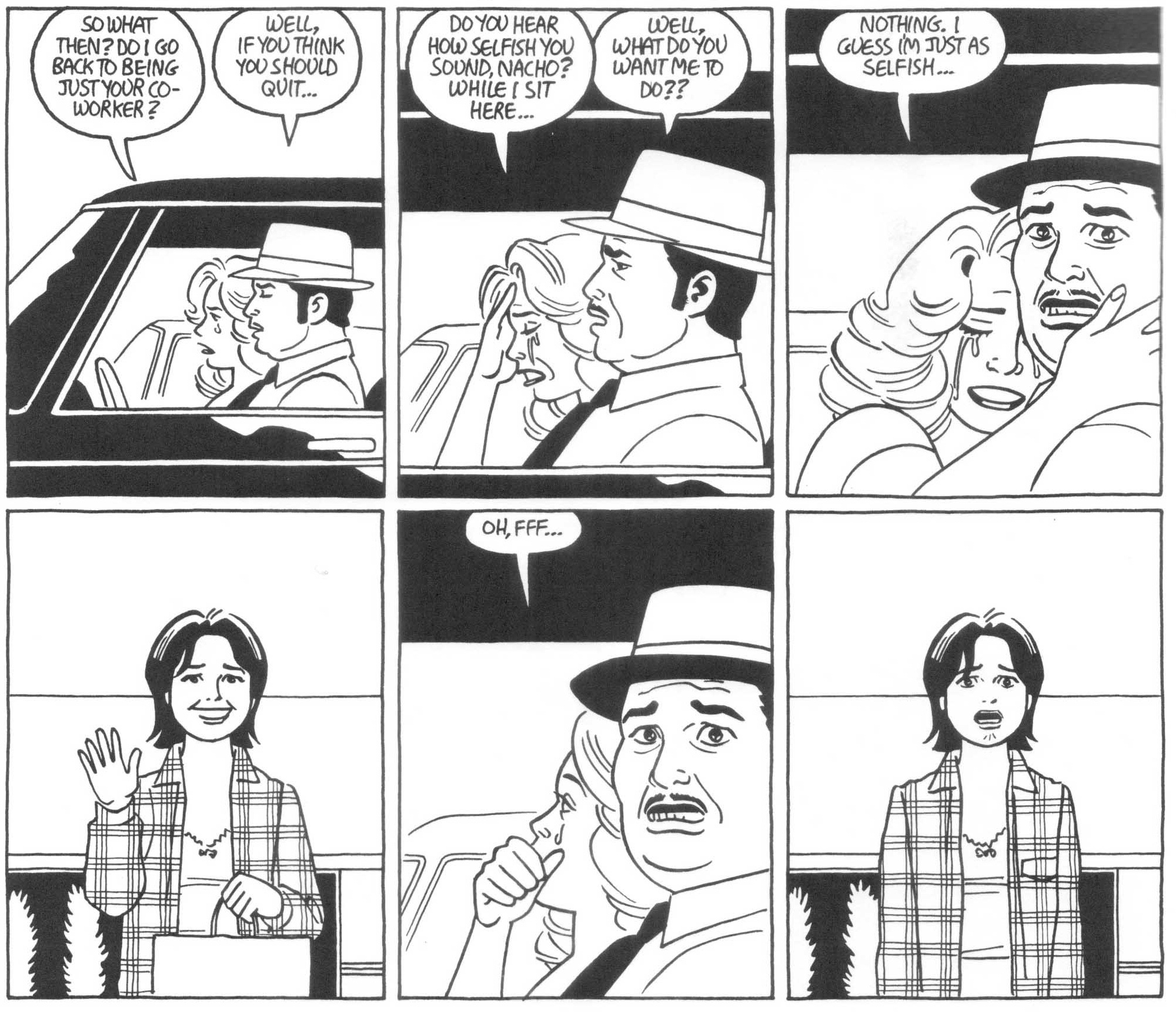

But still; there’s nothing particularly brilliant here, either in the use of language, or in the drawing, or in the use of the comics medium. In this sequence, for example, Jaime uses a series of verbal and visual clichés to present the end of an affair.

“Nothing, I guess I’m just selfish,” she says, as the stylized tears pour down. The camera moves closer, and then we’ve got a shot/reverse/shot. Entirely competent story-telling, sure. Masterpiece by one of the genre’s greatest creators? For goodness’ sake, why?

_________________________________________________

I read a fair bit of the Locas stories for this post — Death of Speedy, The Education of Hopey Glass, The Love Bunglers, bits and pieces of other stories, including Wig Wam Bam. I haven’t exactly grown more fond of Jaime’s work, but I think I have a better sense of what I’m supposed to like about it.

Which would be nostalgia. The difference between “Browntown” and an anonymous short story in a lit magazine isn’t Jaime’s skill, or his handling of plot or theme or character — none of which, as far as I can tell, rise above the pedestrian. Rather, “Browntown” is different not because of what’s in it, but because of what’s outside it: the years and years of investment in the characters, by both the author and his readers. Here, for example:

You see Maggie from a distance, and then in close up. It’s not an especially interesting or involving visual sequence…except that this is the first time in the story that Maggie appears as an adolescent, thirteen years old and post-puberty. For those who have followed Jaime’s work (or even just read the first installment of the Love Bunglers that precedes this piece in Love and Rockets 3), that face is finally, recognizably, the Maggie we know (or one of the Maggies we know). As a result, there’s a charge there of recognition and delight. It’s analogous, perhaps, to Lacan’s description of the mirror stage:

This event can take place… from the age of six months, and its repetition has often made me reflect upon the startling spectacle of the infant in front of the mirror. Unable as yet to walk, or even to stand up, and held tightly as he is by some support, human or artificial…he nevertheless overcomes, in a flutter of jubilant activity, the obstructions of his support and, fixing his attitude in a slightly leaning-forward position, in order to hold it in his gaze, brings back an instantaneous aspect of the image….

We have only to understand the mirror stage as an identification , in the full sense that analysis gives to the term: namely, the transformation that takes place in the subject when he assumes an image – whose predestination to this phase-effect is sufficiently indicated by the use, in analytic theory, of the ancient term imago.

This jubilant assumption of his specular image by the child at the infans stage, still sunk in his motor incapacity and nursling dependence, would seem to exhibit in an exemplary situation the symbolic matrix in which the I is precipitated in a primordial form, before it is objectified in the dialectic of identification with the other, and before language restores to it, in the universal, its function as subject.

As always, Lacan is a fair piece from being comprehensible here…but in general outline, the point is that the child sees its image in the mirror — an image which is whole and coherent. The child identifies itself with this image, and so jubilantly experiences, or sees itself, as coherent and whole.

In her book Reading Lacan, Jane Gallop points out that the jubilation and excitement of the mirror stage is based upon temporal dislocation:

…in the mirror stage, the infant who has not yet mastered the upright posture and who is supported by either another person or some prosthetic device will, upon seeing herself in the mirror, “jubilantly assume” the upright position. She thus finds in the mirror image “already there,” a mastery that she will actually learn only later. The jubilation, the enthusiasm, is tied to the temporal dialectic by which she appears already to be what she will only later become.

Thus, there is a rush of pleasure in seeing the woman Maggie in the adolescent Maggie; the future image charges the past.

But the mirror stage is not just about recognizing the future in the present. It’s also about creating the past. Gallop explains that before the mirror stage, the self is incoherent; an unintegrated blob of body parts and non-specific polymorphous pleasures. But, Gallop continues, this is an illusion; the self cannot be an unintegrated blob before the mirror stage, because it is the mirror stage that creates the self. Thus:

The mirror stage would seem to come after “the body in bits and pieces” and organize them into unified image. But actually, that violently unorganized image only comes after the mirror stage so as to represent what came before.

The mirror stage, then, provides an image not just of the future, but of the past. The subject “assumes an image” not just of what she will be, but of what she was; the coherent image of the self is not just an aspiration, but a history. When Lacan says:

This jubilant assumption of his specular image by the child at the infans stage, still sunk in his motor incapacity and nursling dependence, would seem to exhibit in an exemplary situation the symbolic matrix in which the I is precipitated in a primordial form…

the specular image that is assumed is precisely the infans stage, and the I that is precipitated is precisely the primordial form. The jubilation is not just in seeing a future coherent self, but in seeing a past self that is coherent with both the present and future.

Or to put it another way, the attraction of nostalgia is not the idealization of the past, but simply the idea of the past — and of the future. It’s the romance of self-identity. Hence, nostalgia in the Locas stories isn’t a function of actual time (a reader who has in truth read for decades) so much as it is a projection of imagined history. How many times has Jaime drawn Maggie (or Perla, or Margaret, or…)? All of those images are a part of a self, snapshots of a connected chain of bodies linked from infancy to middle-age to (presumably) death. As Frank Santoro says in his piece about the Love Bunglers:

Something extraordinary happened when I read his stories in the new issue of Love and Rockets: New Stories no. 4. What happened was that I recalled the memory of reading “Death of Speedy” – when it was first published in 1988 – when I read the new issue now in 2011. Jaime directly references the story (with only two panels) in a beautiful two page spread in the new issue. So what happened was twenty three years of my own life folded together into one moment. Twenty three years in the life of Maggie and Ray folded together. The memory loop short circuited me. I put the book down and wept.

The power of the Locas stories, what makes them special, is not any one story, or instant, or image, but the knowledge of the whole — not in the sense that each part contributes to a greater thematic unity, but in the sense that simply knowing there’s a whole is itself a delight. You can read the Locas stories and know Maggie, not as you know a friend but as an infant knows that image in the mirror — as aspiration, as self, as miracle.

_______________________

And, of course, as illusion. The reflection in the mirror, the coherent past and present I, is a misrecognition — it’s not a true self. Jaime’s use of Maggie as nostalgic trope, then, functions as a deceptive, perpetuated childishness; a naïve acceptance of the image as the real. Consider Tom Spurgeon’s take on “The Death of Speedy”:

Hernandez’s evocation of that fragile period between school and adulthood, that extended moment where every single lustful entanglement, unwise friendship, afternoon spent drinking outside, nighttime spent cruising are acts of life-affirming rebellion, is as lovely and generous and kind as anything ever depicted in the comics form.

That could almost be a description of “American Graffitti”, another much-lauded right-of-passage cultural artifact noted for its compelling, yearning encapsulation of time. I would agree that this is a major characteristic of Jaime’s work…but whereas for Tom that’s the reason Jaime’s a favorite creator, for me it’s the reason that he isn’t. Hopey’s nightmare hippie girl schtick; the shapeless but coincidence-laden narratives; the sex, the violence, the rock and roll — it all seems at times to blur into that single repeated punk rock mantra, “That was so real, man. That was so real, man. That was….”

But while I don’t necessarily need to read any more of Jaime’s work ever, I do think that there are times when the nostalgia in his stories becomes not just a symptom but a theme. For example, looking again at that image of the suddenly post-pubescent Maggie from “Browntown”.

As I said, this is a moment of recognition. But whose recognition? The panel is from the perspective of Calvin, who is both Maggie’s little brother and the sexual victim of the boy Maggie is talking up. While readers see suddenly the grown-up Maggie they know and love, Calvin is seeing, perhaps for the first time, a grown-up Maggie who he does not know, and who he fears and resents as a potential sexual rival. The reader’s image of Maggie — the shock of her newfound adulthood — lets us see her, to some extent, as Calvin sees her (and, indeed, allows Jaime to subtly tell us how Calvin sees her). At the same time, looking through Calvin’s eyes inflects and darkens Maggie’s new adulthood; the overlapping perspectives capture not just the excitement of growing up, but its dangers and sadness as well. The mirror image is also a primal scene, the discovery of self also a loss of innocence. What Gallop says of Lacan might also be said of Jaime:

When Adam and Eve eat from the tree of knowledge, they anticipate mastery. But what they actually gain is a horrified recognition of their nakeness. This resembles the movement by which the infant, having assumed by anticipation a totalized, mastered body, then retroactively perceives his inadequacy (his “nakedness”). Lacan [or Jaime?] has written another version of the tragedy of Adam and Eve.

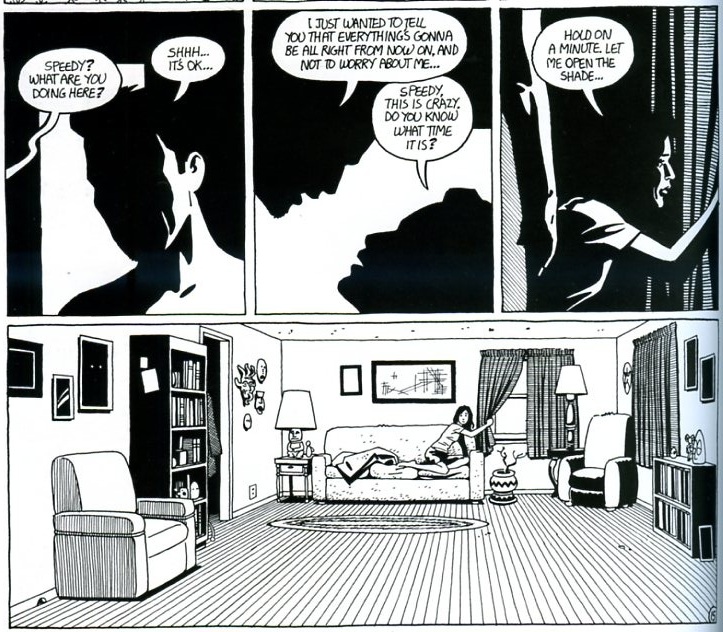

Another example of the way nostalgia is thematized is in the ghost scenes in “The Death of Speedy.”

On the one hand, this, like the entirety of the derivative “West-Side Story” plot, is fairly standard issue melodrama. But in the context of Jaime’s oeuvre, there’s something (eerily?) fitting about Speedy’s disappearance into a darkened silhouette, a kind of icon of himself. Speedy’s a projection, a specter given meaning only by his past. But that’s not just true for Speedy — it’s true for everyone in the Locas stories, who appear and then disappear and then reappear further up or down the timeline. A ghost is a kind of distillation of nostalgia, a memory that walks. At moments like this in Jaime’s work, the compulsive authenticity claims become almost transparent, as everyone and everything turns into its own after-image. We cannot see the present without seeing the past and the future, which means that we don’t ever see anything but an illusion, an image of coherence.

This is perhaps one way to read the conclusion of The Love Bunglers. Many people have read it as a happy ending for Maggie and Ray; the final triumph of romance after many trials. Thus, Dan Nadel:

In the end we flash forward some unspecified amount of years: Ray survives and he and Maggie are in love and Jaime signs the last panel with a heart.

And maybe Dan’s right. But it’s also certainly the case that that ending is only reflection; it’s what we want to see in the mirror.

Two Maggies side-by-side look in two mirrors at two Maggies. We see doubles doubled, the Maggies we love seeing the Maggies we love. This is the way cartooning works; one image calls forth another and another, the characters become themselves through sequence and repetition. As Dan Nadel says, “It just works. They’re real.”

But at the same time as it solidifies Maggie, the doubling of the mirror stage also disincorporates her. The second Maggie in the mirror…doesn’t she look younger than the first? Is time passing, or is the mirror image just an image — the future Maggie that present Maggie needs to see in order to make the past Maggie cohere? If the happy-ending Maggie looking in the mirror is just a dream to retroactively solidify the grieving Maggie, perhaps the grieving Maggie looking in the mirror is herself a dream, an image to confirm the tragedy. And so it goes; Calvin’s unlikely assault is an image there to give weight and shape to his childhood trauma; Maggie kisses Viv and is rejected by her to give weight and shape to their past — or and simultaneously the past gives weight to the future, and on and on, image on image, through the never-ending jubilant shocks of misrecognition.

__________________

Jaime’s oeuvre, I think, can be seen as a mirrored engine; turn the crank and nostalgia is infinitely reflected. It’s an impressive delivery system. As with the Siegel/Shuster Superman, or the Twilight books, I can see the appeal, even if, for me, there’s something more than a little off-putting about the efficiency of the mechanism.

__________

The index to the Locas Roundtable is here.

Nostalgia… this will fit well with what I’m working on.

“Supposed to” like? Who says? Is there a rule? No one is supposed to like anything.

I seem to recall that you hadn’t read Jaime’s work before this, and so the way it sounds like you went about it is a bit like reading the last chapter of a book and then going back to read a few pages here and there in the earlier body…judging it by the ending as it were. Kind of a perfunctory reading.

Apart from that I got the first issue of L&R when it came out, I really came in with the NY Times strips which was intended as an entry point I think…but I can’t imagine what someone would think if they only read Love Bunglers and Browntown. Or, you are that person and you show how that isn’t happening. It’s a much larger tapestry that gains in power in its cumulative effect.

My whole essay is devoted to the idea that Wigwam Bam, esp., but also many of the later Locas stories are dedicated to the rejection of the notion of authenticity, or the “that’s so real man” syndrome….using Freud more so than Lacan… So, while there is nostalgia in these stories, there is also a frank acknowledgment of how that nostalgia is empty…how there is nothing, really, to be nostalgic for, no “1 real thing” to anchor memories or subjectivities, etc. Certainly, all of the ghosts and mirror-images you cite suggest that to be the case. You want to read Jaime’s use of these things as formulaic, while your reading of them is a deconstructive of such formulas of authenticity….but why? Might it just as easily be said that his use of such things is doing precisely what you believe yourself to be doing?

Anyway, I didn’t really want to talk about ghosts and mirrors and suchlike… I had other fish to fry…though I’m not sure I’ll actually get to it.

I have to admit I haven’t read the new stories, but I have to wonder in this context, when Calvin sees Maggie chatting up that boy he’s viewing her in a new light certainly. But in that moment is it that of “potential sexual rival” or “potential–possibly unwitting–co-conspirator?” The sister he looked up to is suddenly fraternizing with the person who’s harmed him.

The affair-ending sequence with the cliched tropes, the Lichtenstein-esque crying woman, I feel Jaime’s work has always had a touch of that camp element to it, that very old comic book/telenovella feel from the earliest days (which I’m re-reading for this) of spaceships, dinosaurs, and ridiculously chisel-jawed Rand Race. I guess it could be taken as a post-modern riffing on those elements , or perhaps it was a sincere, direct absorption of those kinds of things into his narrative/visual style. Maybe a bit of both.

James, I think even in your comment there’s a pretty strong suggestion that I’m supposed to like it.

I’ve read four or five of Jaime’s books now, and bits and pieces of a bunch more. As I’ve asked in other contexts, I wonder at what point I’m allowed to have an opinion? I really don’t think reading more is going to make me like it better (not that I hate it — I’m just not wildly enthusiastic.)

Eric, I don’t think your characterization of what I’m doing is exactly right. I say that Jaime is thematizing these issues. I don’t think he’s unaware of what’s happening with the mirror or the ghosts. The point isn’t that it’s too authentic solely, but rather that I find the obsession with nostalgia and authenticity (whether to embrace them or disavow them (and I think Jaime does both)) both wearisome and familiar. It’s certainly skillfully done, and I can appreciate that about it…but it still feels like program fiction, and like one of the main engines of pleasure is supposed to be the identification (again, whether embraced (mostly) or occasionally disavowed.) And that just doesn’t move me that much.

Jenny, I think it’s both with Calvin; there’s definitely a complicated sense of betrayal/jealousy.

I think that’s a good point about the campiness. I think one way nostalgia is strongly inflected in Jaime’s work is precisely through those visual cues. I didn’t really talk about it here, but I probably should have.

Oh…James, just in case people are curious. I read Ghost of Hoppers a while ago. Then I read Death of Speedy. Then I read Miseducation of Hopey Glass and read around in some other books (Wig Wam Bam and others.) Then I read Browntown and Love Bunglers. There may have been something else in there, but I think that was the basic sequence.

Wow, wha..? I don’t see Calvin as jealous in any way. He’s being raped on the long term and he doesn’t like it. Ding dong, people of either sex do not like being raped! He can’t seem to extricate himself, his assailant is threatening his family. No one is protecting the child Calvin. When the (unnamed) scumbag goes near his sister, it is the catalyst that makes Calvin act to protect his sister from said scumbag.

No…I think he’s jealous as well as/as part of being traumatized. And I think when he kills the older boy, it’s in part out of jealousy (as well as vengeance.)

Calvin is definitely abused, and it’s statutory rape, which is rape. But it’s not exactly non-consensual, and I think Calvin’s feelings about it are complicated and conflicted. Which seems believable to me.

So…in your reading Maggie is a sexual rival for the older boy’s affection? Maybe to some degree, but I would also say the the reverse. The older boy is a rival for Maggie’s (sexual) affection. Calvin’s a confused and f’ed up youngster by this point, of course…and later he’s an even more confused and f’ed up adult…but he’s actually fairly obsessed with his older sister and anyone that goes near her sexually (like Ray later). It’s more competition FOR her than competition WITH her (and Calvin knows firsthand what the older boy really wants out of all of these interactions). Calvin is protective of Maggie, but it’s certainly arguable that it goes beyond that (esp. to the degree that everyone in Locas–readers and characters alike–falls in love with Maggie. Hopey, Ray, Speedy, Frogmouth, basically everybody).

To call Calvin’s relationship with the older boy “not nonconsensual” isn’t exactly the same thing as calling it consensual, I guess, but it still makes me squeamish. The whole reason statutory rape IS rape is because people of Calvin’s age (when this whole cycle of abuse starts) aren’t really capable of making rational, mature decisions about sexuality. He’s forced into it by the older boy’s power, assuredness, relative social position, etc…none of which Calvin really understands. So…it is nonconsensual, because Calvin doesn’t really have the wherewithal and understanding to give consent. The fact that he kind of becomes attached to the boy and goes back to him even when, certainly, he could avoid it once he knows what’s coming, isn’t really relevant. It’s the trauma of the repetitive rape that leads him to keep coming back, not some kind of informed consent. To call it “not nonconsensual” plays with something of the “blame the victim” logic which makes me uncomfortable. I’m sure that’s not exactly what you mean…but the double negative obscures the indirect claim that this is somehow “consensual”–which I would resist (at least insofar as I recall…since I haven’t read it since it first came out).

I would say, though, that I don’t really think Browntown or The Love Bunglers are the best of the Jaime stories. I know everyone gushed at Browntown, but the “story of child abuse” thing does strike me as somewhat overplayed…and the conclusion of “The Love Bunglers” struck me not as overreaching for emotion and nostalgia.

Wigwam Bam and Chester Square work better for me as Jaime’s best work and as emotionally rich. I like Death of Speedy, but it doesn’t have the same depth or complexity… So, WWB/Chester Square is the sweet spot for me. What comes before seems not as assured, complex, etc., and what comes after feels like a grasping for “what comes next” and how to keep the characters going “after the end” (of the original Love and Rockets serial). I like alot of the stories, both before and after, but they all seem flawed to some degree. Browntown/Love Bunglers are not exceptions to that.

Should say “struck me AS overreaching” Re: conclusion of Love Bunglers

“esp. to the degree that everyone in Locas–readers and characters alike–falls in love with Maggie”

See — not me. I kind of resent the extent to which I’m supposed to fall in love with her, reiterated by the way everyone else throws themselves at her. I don’t dislike her or anything, but she’s not a character I have special affection for or interest in. Like I said, it’s like Bella or Superman in that way; the weight of the emotional response depends on identifying with/desiring a character who I don’t (or not to the extent I’m supposed to, anyway.)

I agree with what you about Calvin for the most part. I wasn’t saying that it wasn’t rape, or that he was to blame. He’s absolutely not to blame; he’s a kid.

While I get where you’re coming from w/the Bella/Superman parallel I’m not sure that in Locas the weight of the emotional response depends on identification or desire. In the case of Locas the weight of the emotional response has a lot to do with the various parts coming together in ways upsetting, amusing, or otherwise affecting. You allude to this throughout the essay. I realize that Maggie is almost always at the center of the narrative, but as a tapestry I don’t think that narrative reducible to her in the way that a Superman comic always comes down to Superman (I can’t comment on Bella as I’ve had zero exposure to Twilight).

Oh, and I want to echo that your point about nostalgia being a driving force L&R makes a lot of sense to me. The characters do often seem to be striving for a past that was never really theirs. Anyway, it’s something I’ll be thinking about for a while.

Holy moley. Consensual, statutory!!?? Jealousy??!!! Calvin “goes back”?? I think not. Look at the panels of Calvin being fucked by that kid.I see nothing in his face that indicates anything other than misery and a horrible resignment to what he must endure. The bigger kid threatens Calvin’s family so Calvin will do what he wants. When the kid takes it further than threats, it is his undoing. Anyone who has been bullied knows that it can seem relentless and unending, when there is no way to avoid the bully and no one will help. Why do you think this issue is being legislated on??

These rape discussions do make me despair.

Calvin’s being abused. But when he confronts the older boy, he says something like, you promised me I’d be the only one.

If Calvin were able to see himself as being victimized, or able to see what was happening to him as entirely wrong and against his own will, he could tell somebody about it and it would stop. The reason that statutory rape exists is because it’s often impossible for children to make those kinds of distinctions. Calvin hates his rapist, but he has other feelings for him as well. That doesn’t make what happens to him not rape. It does show how the rape is accomplished, and why it was so complicatedly traumatic.

Noah…obviously not all readers will “fall for” Maggie (and predictably, you’re one that doesn’t)….but it is true that nearly all characters do fall for her…and that’s part of the thematics of the stories. I don’t think it’s necessarily (or completely) an effort to draw readers into loving her. Rather, the fact that everyone in the storyworld loves her serves particular functions in the story (as does her incapacity to end up in a longterm fulfilling/loving relationship that lasts despite all the love she receives).

I agree with James that it’s somewhat problematic to psychoanalyze a kid and to project motives for why he allows himself to be raped, etc. But…a key point here… Calvin is not a real person. All we’re analyzing is what a story means (what the story itself implies about his psychology, etc.) We may be “wrong” about what Jaime Hernandez intends to convey (though nobody’s really talking fully about author intent), or we might disagree about a character’s evident motivations, but we’ll never be wrong about why a real kid named Calvin does what he does…That kid doesn’t exist. If there are kids who have undergone similar traumas (and undoubtedly there are), reading into Calvin’s motivations or lack thereof doesn’t tell us anything (or very little) about them. The story is, if anything, already an interpretation of the way statutory rape works in the “real world”–not a mimetic depiction of such a thing. When we interpret Browntown about these things, we’re interpreting what someone else’s interpretation is. As such,we might learn about how some people view statutory rape…but we won’t learn about statutory rape itself.

Of course, James can say that how we interpret these scenes is psychologically revealing about us… so, he might want to interpret our interpretation of Hernandez’s interpretation… and, I guess, more power to him…but the outrage seems to stem from mistaking what people are doing when they interpret/criticize art.

Hmmm, yes, I am discouraged by what I see others reading into this, very much as I was with the Watchmen business. Jaime is very deliberate in what he shows and says. I don’t see Calvin saying “you promised me I’d be the only one” in any way as a declaration of jealousy. Rather, I take it to mean that Calvin made a pact of sorts with his rapist that he would endure the bully’s attentions alone, in order to spare others what is happening to him.

I think it can be both. Calvin’s motives are somewhat opaque, probably even to himself.

I don’t see much opacity. Calvin seems pretty believably motivated and I think his actions play out with a traumatized logic throughout the story. I’ll tell you what though, if and when I deal with issues like this in my own work, I’d better make efforts to avoid potential misreadings—so much for subtlety.

I can’t imagine “loving” a cartoon character. In comics, the characters comprise the visual and textual “voice” and sensibilities of their author. Maggie is Jaime. So is Ray and Doyle and Frogmouth etc. If you all are falling for someone, it’s the author. Jaime is very good as a man at writing female characters and he is able to create an empthetic response in the reader to the roles he puts his characters through; it is literally acting, what he has the characters saying and doing and how he times and reneders their expressions and gestures. All love goes to the power of his writing via the interaction of text and art.

I’m tempted to jump into this discussion on various points, but will for now only make the significant one (I hope) that the form of nostalgia being evoked here is the contemporary, commercialized notion, which has become warm and fuzzy. But to my mind, Jaime is closer to the Greek original, which was eloquently summarized by the experimental filmmaker Hollis Frampton: Was reading for work and encountered this Hollis Frampton quote: “In Greek the word means ‘the wounds of returning.’ Nostalgia is not an emotion that is entertained; it is sustained. When Ulysses comes home, nostalgia is the lumps he takes, not the tremulous pleasures he derives from being home again.” (As many of you may know, Frampton titled perhaps his most famous film after this concept, which he wished to distinguish from the notion of the “good old days” it has come to mean in recent American usage. I think the pain of returning, to a home that can never be the home one left, is a notion central to Jaime’s work as his main characters have moved away from Hoppers.

Oops, I did a poor cut and paste on that quote — just remove “Was reading for work and encountered this Hollis Frampton quote” and my comment should make a bit more sense…

I mean, obviously he isn’t the characters, but he generates them. It’s why I don’t see the characters as being as important as the people who make them, why, for instance, the contructs that Kirby initiated mean nothing to me in someone else’s hands.

Corey, I was trying to use nostalgia in a not entirely derisory way….

James, I think desire and identification are central to lots of art. There certainly are characters I love or identify with in various ways (Elizabeth Bennett for example — how can you not love her?) And creators aren’t exactly their creations, just as dreams aren’t exactly the dreamer.

Let me be the first to tell you your grad school days will eventually fade. Whatever you like won’t have to be screened through the most fashionable theorists around (you might even find unfashionable ones to frame your complaints).

My grad school days were a long time ago, and Lacan is a more recent interest, really (I was more into Foucault back then.) That Jane Gallop book is great, incidentally; very understandable and smart and fun.

Anyway, you’re hardly the first to tell me that the comics subculture is very leery of theory.

“Leery of theory” is a nice turn of phrase.

The resistance to theory within comics criticism (see decades of The Comics Journal, for instance) is nothing anyone should be proud of … that fact that comics criticism is still seeking to establish its brand of formalism puts in on par with literary and film criticism of the 1950s. So I have no trouble with the invocation of theory in this regard …

I didn’t see the use of the term “nostalgia” as derisive, but I didn’t see it getting at what the original term conveys, which is the pain of return, not the pleasure, and Jaime is increasingly a poet of pain …

Quick note: the phrase “right-of-passage” should be “rite of passage.” Observation: I think the appeal of this particular issue hinges on the reader’s history of experiences with the characters. Reading “a fair bit of the Locas stories” won’t really cut it, since individual L&R episodes need to be seen in their relation to longer arcs of development. These stories resonate powerfully with earlier material, and potentially shift the reader’s relation to it. People like what they like, but the richness of “Browntown” and “The Love Bunglers” is hard to perceive without such a history of reading.

Hey Edgar. Well, I sort of argue in the piece that the appeal is nostalgia and a history with the characters. I’m skeptical that I’d necessarily be more enthusiastic if I read more…though obviously it’s hard to say how I’d feel if I grew up with them.

Both Noah and Domingos have read lots of Love and Rockets and almost all of the important bits as well. They just don’t like Love and Rockets that much. I keep trying to warn them off it (Noah more than Domingos) but they just won’t listen to me. Such is their masochism.

Hey all. There’s some kind of glitch with the server apparently and the site is running slow. I talked to our host and supposedly they’re working on it. My apologies for the inconvenience.

But I’m not convinced that “nostalgia” is the best term to describe what’s happening in L&R. Nor am I persuaded by this: “The power of the Locas stories, what makes them special, is not any one story, or instant, or image, but the knowledge of the whole — not in the sense that each part contributes to a greater thematic unity, but in the sense that simply *knowing* there’s a whole is itself a delight. You can read the Locas stories and know Maggie, not as you know a friend but as an infant knows that image in the mirror — as aspiration, as self, as miracle.” If simply *knowing* there’s a whole results in delight, why weren’t you delighted? No. I don’t see how you can believe your own argument. The simple fact is that a comic would be discontinued if individual stories didn’t satisfy readers, and any serialized comic is one in a sequence of narratives in which every panel extends, contributes to and alters the (imagined, forgotten, poorly remembered) whole-as-it’s-developed-so-far. What you’re saying (or what you’re saying Santoro is saying) is that Locas is special because Locas, well, encourages the same recursive experience any comic encourages (but Santoro isn’t really saying that). There might be a special recursive pleasure Locas readers get out of Hernandez’s insistent reimagining of the comic’s own past, and by the duration of the title across time, but this doesn’t get at the appeal of L&R for its readers. What you’re telling us is that you don’t understand why people like “Browntown” as much as they do. Okay. That’s fine. But telling us it’s because readers are nostalgic for a misremembered past sounds a bit snotty (“Maybe Lacan and I can let them in on their particular conundrum”).

I’d also say what you’re really describing is your own Proustian sense of disappointment.

I reread the story and have to correct my memory on one point: actually, Calvin doesn’t kill his rapist to protect Maggie—Calvin’s earlier retaliation was for that reason, but the bully would not have access to do them harm in future, since the family is moving away. Instead, in the end Calvin takes revenge for the years of abuse inflicted on himself.

I cannot believe you actually quoted Lacan, and used the old hoary “mirror phase” as well. Lacan has been utterly defrocked years ago – he is an old fraud; I thought most people in academia were pretty aware of that. I think even the Lit Crit folks left him for dead. Not the best authority to rest your case on. L. Ron Hubbard probably has more cache.

Sorry you’re taking an interest in Lacan now. I would recommend Lyotard and Deleuze any day – they don’t seem as dated and silly.

Edgar, Santoro is saying that the greatness of the story lies in the way it folds together past and present. I think that sounds like nostalgia, though a sophisticated use of it. And again, lots of people argue that the power of the story is in their identification with the characters…which again, sounds like Lacan to me.

Tim, I wouldn’t want to undergo Lacanian analysis, but his theories are still central for a lot of film theory, especially feminist film theory. Gallop’s wonderful book is pretty recent; other theorists who use him in one way or another include Kaja Silverman (whose book Masculinity at the Margins I’ve been reading) and Carol Clover (who’s awesome.)

I haven’t read Lyotard, but just read (maybe reread?) Deleuze’s essay on masochism, which is interesting though I’ve got problems with it.

Allow me to elaborate for readers who don’t know Proust. In scene after scene of In Search of Lost Time, the narrator’s idea of things (the shape that a famous stage actress, or Venice, or a particular bit of architecture has taken in his mind) is continually confronted with the reality of those things, which leads to sometimes crushing moments of disappointment. Where are the pleasures others have described? How can a world that arises in so many convincing, vivid accounts match up with this small, dour, lackluster production? It’s an experience all of us have, most painfully when the idea of the person we love clashes with the reality of that other whose actions, attitudes and words break with what we thought we knew. What this essay mostly does is play out the consequences of that disappointment, in a kind of eloquent tantrum. Proust’s answer to this same set of circumstances is different, since what’s taken place takes place in an atmosphere of highly ironic comedy. The idea that we can’t see a raving beauty in the photograph shown to us by a jealous lover is seen, wisely, as funny. The narrator has no need to disparage the thing the lover loves (“Browntown” is like Twilight? Really?). He acknowledges the (often painful) comedy of granting value to anything, since time liquidates all values in the end.

Santoro is describing a moment of recursion, not nostalgia (notice the phrase “memory loop”). Nostalgia is explicitly a desire to return to the past. If Santoro said he wanted to be 25 years younger, or wanted to be living with his mother, etc, I’d believe you. But I think you’re having your own moment of speculative misrecognition.

Edgar: I’m a University Professor and I teach film production and studies. So yeah, I know there’s still a lot of Lacan kicking around in film studies. But trust me, he’s associated with a waning, esoteric and deliberately occult part of the discipline that’s losing popularity as we speak.

It’s still there, but only because people who need tenure need to use something incomprehensible to write about. The newest and best stuff does not rely on the old faker.

I think Lacan’s fashionability or lack thereof is irrelevant. If quoting Lacan helps Noah or his readers see something new/interesting/relevant/revelatory in Jaime’s work, it hardly seems important that someone has “defrocked” him. If it doesn’t help with that kind of insight, it’s not Lacan’s fault…

Tim, it’s me who’s interested in Lacan, not Edgar. And as Eric says, if you want to engage with the ideas, do so; if not, it’s not clear what you’re bringing to the conversation. Whatever axes you have to grind with academic politics really aren’t especially relevant to this discussion.

Edgar, I think Santoro is talking about both recursion and nostalgia. Nostalgia isn’t just a desire to return to the past (is sort of the point of the piece); it’s also a desire to create the past; to reaffirm its existence.

The reading of Proust is interesting, but I’m not exactly sure why you think I’m throwing a tantrum precisely? I don’t like Jaime as much as others have, but it’s not a world-crushing disappointment or anything. I’m interested in figuring out what in his work doesn’t work for me and what does. It’s not a case of existential ennui, where nothing can be as good as I expect; there are plenty of comics and works of art I love and that don’t disappoint me. I mean, if I reviewed Twilight negatively, would you assume that it was because I had failed to understand the existential irony of existence? Or would you just assume that I didn’t like it?

Comparing Jaime’s work to Twilight or early Superman is obviously something of a sneer, but it’s not an effort to say that Browntown is worthless. I like Twilight and Siegel/Shuster both.

Lacan hasn’t helped the insight. Ironically, it’s left him blind (here DeMan shakes hands with the old psychoanalysts), when the entire essay hinges on the issues of seeing and not seeing. Berlatsky claims to see, but doesn’t; he quotes, but doesn’t read closely enough. He sees what he *wants* to see, and makes impossible claims about the sight of others (the performative contradiction that “[t]he power of the Locas stories, what makes them special, is not any one story, or instant, or image, but the knowledge of the whole”). All in all a comedy of blindness.

You’re welcome to call me “Noah.” It’s a blog after all. Also, I’m not the only Berlatsky in the conversation; Eric’s my brother.

So when I look in my wallet for the change I remember getting last night, that’s nostalgia? No, I’m sorry. It isn’t. Nostalgia has a more specific meaning you’re attempting to dilute. Santoro’s description might be melodramatic, it might contain elements of bathos, but nowhere in it is a desire “to create the past” at work. As he explains (“Something extraordinary happened”) Santoro steps into the time machine *by accident*. You’d be better off using Dr Who as your main theorist here (you’d be on safer ground with ideas about repetition and difference).

Well, surely there’s an emotional component; looking in your wallet isn’t a desire to create the past, I wouldn’t think (though it does depend on the assumption that there is a past, of course.) But the emotional charge in Santoro’s description, I think, comes from the reification of the past; the sense that the past is being recreated and validated in the present. He doesn’t have to return to the past because the past is being folded into now.

I don’t really know what work you expect the “by accident” to do for your reading? The whole point of the analysis I’m doing is that sequence is vitiated; that pretty much makes mincemeat of intentionality too.

In terms of blindness…it’s maybe worth noting that using Lacan as I’m doing is a helpful way to call into question whether the ending events of Love Bunglers happen or are a dream, or whether that distinction even can be said to matter. Many positive assessments of the story (including Frank’s) rely on an assumption that the happy ending is happy and an ending.

Where’d you come here from, by the way, Edgar? We’re getting a ton of traffic to this post and I’m curious where folks are finding it linked….

I include the phrase “by accident” because what happens to Santoro takes him by surprise; since your notion of nostalgia is explicitly formulated as a “desire to recreate the past; to reaffirm its existence,” this implies agency. If he desired such an accident of recursion, he doesn’t say. (On a different note, looking into my wallet for change is surely a way to affirm what happened the night before. I’m *believing* your argument, not doubting it.)

My point is that your Lacanian analysis prompts you to see things that really might not be there, and to not see things that are. I also think you expand the idea of nostalgia past its breaking point.

A friend of mine posted this to my Facebook. Could it be circulating?

Desires aren’t always clear before they’re realized, and intentionality is always hard to parse (especially in a Freudian context.)

The wallet issue is an interesting question. It’s possible that it’s most useful to think about Lacan in terms of past and future identity; that is, the continuity of past and future selves. There’s obviously not the emotional content in randomly looking in your wallet as in Frank’s reaction to the book — though it’s interesting that the reality of the past is in your narrative instantly connected to money and economics, perhaps? That’s a different kind of authenticity claim, but it’s still an authenticity claim, I’d argue — so maybe not so far removed from Frank’s reaction after all.

I think the definition/discussion of nostalgia I’ve offered is pretty specific. It’s obviously a bit idiosyncratic, but I found it useful in thinking about Jaime’s work in any case. As for Lacan prompting me to see things that aren’t there…you’re just saying you don’t like Freudian analysis, basically. The question of what is and isn’t there is pretty central to Lacan and to my discussion — you seem to be claiming that you have some sort of privileged access to what’s really there that allows you to make these determinations without some sort of theoretical reference point. Which seems dicey to me, especially in that the points of contention are pretty abstract (how do you define nostalgia; what constitutes a motivation.)

Yeah, I guess it’s circulating in facebook. You just never know what’s going to catch people’s attention….

I’m glad to see some conversation about the happiness of the ending. I thought the conclusion was so powerful because of its emphasis on the costs exacted for this “happy ending.” Yes, Ray and Maggie are together, Maggie has helped nurse him back to health, and Maggie is a mechanic again. But we don’t know anything about the nature of their home life or relationship now, and I’m not sure I read that tear Maggie cries in the final panel as a tear of joy unalloyed; it seems that she’s as much Ray’s caregiver as his wife or lover, maybe more. It’s not clear what Ray does all day — not housework, we know, and if it’s art, well, as it turns out the art that Ray was making pre-injury is pretty lame. He says he remembered something new, but it turns out he didn’t, really.

It’s here that the opening one-page vignette about Yax and his family pays off. I think people tended to read it as a sort of quiet affirmation of the power of real love, of the complicated emotions that tangle people together in a long relationship. And that’s part of it. But Yax’s situation here on the first page of issue 4 is strikingly parallel to Maggie’s on the last page: he comes home from work and spends the evening taking care of people who don’t/can’t/won’t communicate with him, or whose ability to communicate with him is severely diminished. Surely this is as much the reason for Maggie’s tear as her deep and abiding love for Ray, or his happiness that he is still alive?

I want to be clear that I’m not saying that people who end up as caregivers for their partners love them any less or anything like that — most people in a long-term relationship will end up giving or needing care or both. But I think it’s significant that Maggie’s relationship with Ray is only finally possible once he needs her to take care of him every day — and it’s also significant that Maggie is only able to be Maggie the Mechanic again once she’s given up on her dreams of romance, or at least a dream of a certain version of what romance should be like.

I guess this is all fairly obvious, but it does seem to be missing from most discussions of the book’s conclusion, such as the one you cited above from Dan Nadel — maybe just from not wanting to spoil it for people, though.

(In passing and along these lines, it’s interesting that Lettie’s last thoughts before she dies in the car accident are about how much she wants to help Maggie if only she would let her — so self-sacrifice seems to be a theme running through the book.)

Those are interesting points. I think there’s also a question of whether Maggie and Ray are “really” together, though. That is, they’re future life may well be a fantasy happening in Maggie’s head, rather than something which actually occurs in the world of the book.

Noah, I can do without the ad hominem; let’s not guess at my motivations for slagging on Lacan. Fact is, plain and simple, that his are old, outdated, silly ideas about how people think and see. They have little to no relevance to the functioning of the human brain. Name one real developmental psychologist who believes there is such a thing as a “mirror phase.” That’s a very lonely camp.

Science, on the other hand, has a lot to say on the subject – a lot that could be useful to the conversation.

Eric B says that bringing Lacan in to the mix can allow readers to see something new. How useful is this new thing when it’s based on ideas that do not properly describe how people function? I could compare Jaime’s work to the label on a can of tomato sauce, too. Something “new” would result. I’m not sure it would do much to understand Jaime’s comics, how they work, or even why one person would call them “good” and another could disagree.

It’s disheartening to think that comics criticism would pick up on film’s leftovers, especially when film is struggling to legitimize itself by leaving this kind of imprecision behind. That’s my only professional take on the subject.

Lest y’all think this is more of me axe-grinding about Lacan, I’ll spell it out explicitly. Noah, I’m not sure how much of this we should be taking seriously, considering the fundamentals it is based on are 50-year old quack ideas. You’re a smart guy, but your foundation is questionable at best. The rest of your article does seem to boil down to your disappointment that Jaime is “conservative” and does not expand the form. I’m not sure it’s his (or any creator’s) responsibility to do so. At the very end you’re a bit miffed that he’s accomplished at what he does. Still not sure what we should be taking away from that.

Yeah…Lacan’s not that easy to dismiss, I don’t think. His gestures at being science are fairly ridiculous, as are Freud’s…but art isn’t science, you know? Lacan has ideas that I find poetic and thought-provoking in the way I find lots of art thought-provoking.

As an example, maybe — you’re saying that Lacan’s arguments don’t fit with developmental psychology. But if you look at what Gallop says, Lacan’s arguments are explicitly disavowing development even as they flirt with it. It’s a developmental theory that eschews, and even undermines, chronology. Don’t you see how that might be a useful way of thinking about Jaime’s Locas stories, which are both about chronological growth and change and which at the same time are deliberately achronological in many ways?

I love William Marston too, who also kind of believed he was a scientist, and whose ideas are obviously completely unscientific — but which are nonetheless, to me, beautiful and weird and stimulating and often profound. That’s what I look for in art; if it doesn’t fit with the latest theories of developmental psychologists, I really can’t see why I should care.

Jaime doesn’t have a responsibility to expand the form or to write narratives that rise above program fiction; the fact that he doesn’t just means that I can’t really rate him as highly as many seem to want to.

Like I said, Twilight is very accomplished at what it does too; providing an audience with what it wants in a consistent and skilled way is certainly an accomplishment. I tend to like a bit more mystery in my art, though — more surprise, even more confusion. When I feel like I can see how the gears work, I find it less compelling.

Noah, I’d have no issue bringing interesting ideas about art to bear on other arts. Philosophy is full of engaging, beautiful ideas that are fun to think about and can really add to the enjoyment of a work. With Lacan the problem is that he pretends to write science; he is telling you how people think and operate, and it just isn’t true.

At least Freud died thinking he was wrong about everything; that’s what redeems him.

Maybe I’m sensitive here – I live in a country where people actually think creationism is worth discussing. You would not think anti-science would have so many adherents in 2012, and I may be jumping on your invocation of a fraud out of habit.

As to your interest in form-expanding work, it’s one I share. And I’m always glad to read this kind of work. Equally I like the work of people supporting those who engage in pushing boundaries, because it’s hard work and often misunderstood.

But criticizing Jaime for not being that kind of writer is a little unfair and off the point. It’s like criticizing him for not drawing a comic about elves. That’s not what he does, nor has he ever laid claim to it. I understand its not your cup of tea to work within an established idiom. That’s not his fault, though, nor is it a fault of the work NOT to be avant-garde.

One gets the feeling there’s an editor or friend behind you constantly thrusting the newest L&R volume in your hands and shouting “Here! This one is GREAT! You HAVE to like this!” Is there a way you can avoid those assignments? You do not seem to be enjoying them.

Also not sure how much your comparisons to “Twilight” are in earnest. It sounds like the sort of thing one says to really get the opposition wound up. I smell your disingenuousness here; please correct me if I’m wrong.

Nope, grinding into reverse, I read it yet again, it isn’t revenge. I’ll hold it for my piece of the roundtable though.

Freud thought he was a scientist too. And like I said, Marston, who I love, thought he was a scientist. I’m pretty skeptical of scientists anyway in many cases…but the point is, sneering at Lacan or any Freudians on the basis of their intentions seems kind of silly. They’re all about the intentions not being the place to watch, you know?

I think there’s probably a little confusion about where I’m coming from, too. I don’t need work to be avant garde. I like lots of pulp, from Carpenter’s The Thing to Watchmen to Twilight. When I said Jaime seems pedestrian to me, that’s what I meant; it just doesn’t distinguish itself appreciably from a lot of program fiction for me — except perhaps in terms of its serial nature and the long running characters, which I do talk about.

Twilight’s something I’ve thought a lot about over the last couple of years (I’ve written a lot about it if you want to poke about the site.) Certainly it’s a jab to say that Jaime is comparable — but, on the other hand, I really don’t hate Twilight. I just feel like it’s another work that is very smart in terms of catering to its audience.

I don’t have any reason to be disingenuous. I’m not out to get Jaime; I don’t have a stake in disliking him. I’d much prefer to enjoy it, especially since I’ve read several hundred pages of his work at this point. But on the other hand I could like it less. Be that as it may, I have no particular plans to read more in the future — like I say in the piece, I feel like I’ve figured out what I’m supposed to get out of it, which is what I was trying to parse.

My beef is not with Lacan’s intentions. It’s that he’s dead wrong. There’s no sneer here. A Freudian analysis of L&R would be equally problematic, because that stuff is simply dead wrong as well.

Likewise, I’m not so worried about your tastes and whether or not you are consistent with only liking avant-garde works. It’s that you’re criticizing Jaime’s work for NOT being avant-garde when there was no expectation that it would be. It’s also NOT about funny animals, but there’s not much of a legitimate complaint about that.

Your point about not being “out to get” Jaime is well taken, and a fitting admonishment. It’s sloppy of me to suggest it, even obliquely.

Lacan can be objectively wrong about human development (I guess; my faith in developmental psychologists is pretty limited, but anyway….) But he can’t be objectively wrong about how human beings interact with their pasts or with their self-images, I don’t think. Neither can Freud. They both provide stories or theories about the way reality and thought interact — they’re philosophers. I have to admit I can get exasperated with people getting into the weeds of Freudian theory too, and with Freud and Lacan themselves when they make claims to science. Still, lots of smart people have found things in Freud’s and Lacan’s work which are poetic or revelatory or profound. If you think they’re clumsy or dumb or ridiculous, that’s cool, but you need to make those arguments on the basis of what Freud and Lacan say, or what others say about them, not by referencing Western science as some kind of giant normative steam shovel which can whisk abstract philosophical questions out of the way with one puff of its mechanistic hydrocarbons.

I really wasn’t accusing Jaime of not being avant garde. I was accusing him of being pedestrian; specifically of fitting the tropes of program fiction and (to a lesser extent) punk in a way that I find predictable and tedious (though not unendurably so or anything.) There’s plenty of pedestrian avant garde art out there.

OK, I was willing to let this one die down, but you’re still pushing here. Yes, Lacan CAN be wrong about how people interact with their pasts and their self-images. I’ve read plenty of him, and he does not describe my experience whatsoever. Nor that of many people. But this, in fact, what he is claiming to do, much like Freud claimed we all went through an Oedipal Complex or an Anal Stage. Were Lacan, like Proust, to describe his own feelings and experiences and leave the rest of us out of it, I would think he’d be in safe territory. As with a philosopher, we could agree or disagree with him and talk about how fascinating he is.

And yes, I have made an argument about Lacan based on what Lacan writes. The “mirror phase,” specifically, a Lacanian construct you invoked in your article, is hogwash. No developmental psychologist today considers it a valid description of how human beings think, nor do they consider it a stage of any kind of development. Lacan’s argument was that it was an unavoidable and undeniable recognition of self that occurs at a point of each individual’s life. I’m not dismissing him because I don’t like the way he dresses – this is directly related to his work.

I don’t have any “normative steam shovel,” I’ve only read up on the subject. There’s so much interesting stuff going on in proper science, why would you need out of date trifles like Lacan? Perhaps flat-earthers can weigh in on the matter.

So you’re rejecting Lacan on the empirical basis of your own experience? How can you do that exactly? Lacan questions specifically the existence of you, and for that matter of “your” experience. Freud and Lacan also specifically question whether people have full access to what’s going on in their heads. So your arguments end up just being circular, basically — you don’t think Freud and Lacan have anything to offer, therefore you don’t think Freud and Lacan have anything to offer.

Besides…lots of people may not think Lacan and Freud are accurate representations of experience; on the other hand, lots of people think they have something to offer. The Oedipal complex is an extremely apt lens through which to view a lot of superhero stories, for example (Spider-Man, Batman, Superman — it’s a genre replete with daddy issues.)

Again, if you disagree with Freud and Lacan, that’s cool, but you should probably do it in some way more theoretically sophisticated than waving around Western science or evoking some sort of naive empiricism. At least, you should probably do that if you expect me to take your claims seriously.

By the by, I don’t have any trouble with using religion or theology to try to understand experience. Creation myths can provide us with lots of insights into ourselves and the world, even if they’re not scientifically accurate. The idea that we should only use scientifically validated theories to discuss art seems fairly bizarre to me, honestly. We’re not talking about building a better widget.

Sorry; just one more thought. The fact that Freud and Lacan and psychoanalysis in general is not congruent with science or with empiricism is precisely why Freud and Lacan and psychoanalysis have been picked up by feminists. Science and empiricism have a long history of being used as normative levers to solidify as “true” female inferiority. Lacan calls into questions those norms, which is one reason he’s useful in feminist criticism — even though, of course, psychoanalysis was quite sexist itself.

Tim Maloney prematurely wrote, “Your point about not being “out to get” Jaime is well taken, and a fitting admonishment. It’s sloppy of me to suggest it, even obliquely.”

When Noah speaks about Crumb, Clowes, the Hernandez brothers, or any alt-comics luminary, in sharp distinction from the way he deals with fantasy genre and pop culture work, there’s an ostentatious display of his casual acquaintance with those artists, an obsessive obstinacy about his half-assed opinions, and a definite sense that he is actually “out to get them”. That’s an accusation that we should mistrust and second-guess when we feel prompted to make it, because it’s not often true, but in Noah’s case it’s perfectly accurate and just as simplistic as it sounds.

His lightning bolts of insight that Crumb is sexist and racist, Clowes writes about annoying hipsters, Gilbert draws voluptuous women, and Jaime’s work is sentimental soap opera all sit like a bulldog on the surface of those works and inadvertently reveal what separates them from genre pulp, because those works all have depth and are unpredictable beyond their first impression. You really can critique Twilight & most manga at a glance because they are exactly what they appear to be, and any kind of grad-school analysis has to focus on the desires they manipulate rather than any considered statement made by those works themselves which requires thoughtful reading to extract.

I don’t think it’s so much anything Berlatsky has against the artists, although I wonder if the writing which has appeared here on Crumb is about punishing him for embarrassing the Bible, but is against the alt-comics culture which lionizes these artists. Noah is a pseudo-intellectual and entrepreneurial version of the cranks who used to appear on the TCJ message board venting their feelings about “hipsters”.

Oh brother.

OK, no fun anymore. You’re missing the point entirely, perhaps deliberately. You’ve made 54 more assumptions about my argument and are baiting me like crazy. Not interested. We’re never going to come to any agreement here. It was your choice to use an ersatz scientist’s work to discuss art.

And now we probably both have better things to do.

Freud and Lacan are used to discuss art all the time. Shelf-fulls of books using them — some of it good, some not so much. But to dismiss it all because it’s not scientifically rigorous makes as much sense to me as trying to navigate a plane to Mt. Fuji by looking at Hokusai.

I don’t think I made any particular assumptions about you…but of course you should cease the conversation if it’s no longer interesting. Thanks for stopping by to comment.

Russell, you’re correct. My goal in life is to annoy you. Thanks for stopping by to let me know I’ve succeeded.

I’m not sure what Russell is getting at in his incoherent post. Is he saying that Crumb hasn’t exhibited racist proclivities in his more, uh, problematic stories? And is this a subject that has been thoroughly examined? I seriously doubt that.

“The power of the Locas stories, what makes them special, is not any one story, or instant, or image, but the knowledge of the whole……..”

Not completely on board with this. I’d say this is sometimes the case. Or as the overheated reaction to last year’s volume attests, it’s becoming increasingly the case both with the fan reaction and with the stories themselves. Jaime’s best work (hint: his pre-1990 stuff) certainly requires no knowledge of the back story. Yes, nostalgia has always been a recurring theme, even earlier on, but I think distinctions can be made between the more exuberant earlier years and the latter flaccid ones.

I do completely agree with your assessment of “Browntown.” I’d say most of the comics press has done a lousy job of evaluating these last few L&R volumes. Most of the so-called critics who reviewed them had their rose-tinted glasses on, to put it politely.

“I didn’t see the use of the term “nostalgia” as derisive, but I didn’t see it getting at what the original term conveys, which is the pain of return, not the pleasure, and Jaime is increasingly a poet of pain …”

Which needless to say is a problem when you’re talking about what are essentially soap opera characters who are inevitably intended to go on and on and on and on……

Hey Steven. As I tried to say in the rest of that sentence you quoted, it’s not exactly knowledge of the backstory I’m talking about, but the sense that the characters have a beginning, middle and end — that they have a past and future rather than necessarily knowing what that past and future is.

Still, I take your point. A friend on email pointed out that early on Jaime was lauded more for the art than the story? I was reacting to the the more recent critical consensus, which has tended to emphasize the importance of the whole….

I like Russell’s phrase about sitting like a bulldog on the surface of the work. That made me chuckle.

————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

For what it is, “Browntown” isn’t terrible. Jaime’s precocious child narrator is endearing

His ethnic milieu is surprisingly uninsistent and unforced; his traumas are doled out with a disarming lightness — as when Calvin’s years of abuse are limned in the space between panels…

But still; there’s nothing particularly brilliant here, either in the use of language, or in the drawing, or in the use of the comics medium. In this sequence, for example, Jaime uses a series of verbal and visual clichés to present the end of an affair.

“Nothing, I guess I’m just selfish,” she says, as the stylized tears pour down. The camera moves closer, and then we’ve got a shot/reverse/shot. Entirely competent story-telling, sure. Masterpiece by one of the genre’s greatest creators? For goodness’ sake, why?

————————-

A fair appraisal of the story’s merits, and why (as always) exaggerated praise does its creator no favors; virtually challenging part of the, um, Criticsverse to speak out to restore the cosmic balance.

I can certainly see why, in contrast, you find the Marston Wonder Woman stories far more deliciously, even nourishingly wild fare… (Understandably; you’re quite the eloquent speaker for that comic’s virtues.)

Alas, though, there’s always gotta be some wrong-headed perceptions and conclusions:

————————-

But at the same time as it solidifies Maggie, the doubling of the mirror stage also disincorporates her. The second Maggie in the mirror…doesn’t she look younger than the first?

————————-

No, she looks older; just thinner, with calm wisdom in her eyes.

————————–

Jaime’s oeuvre, I think, can be seen as a mirrored engine; turn the crank and nostalgia is infinitely reflected.

—————————

There certainly are ways in which those “flashbacks” show things as being better than in later years; but, is there a relentlessly idealized, warm n’ fuzzy attitude by Jaime and the characters about those times? (Good grief, look at the years of abuse suffered by Calvin in this “nostalgic” past.)

Reading on, I see Corey Creekmur commented superbly — and informatively — on the two aspects of “nostalgia”; though the more common variety is certainly the widely-understood one:

—————————

nos·tal·gia

1. a wistful desire to return in thought or in fact to a former time in one’s life, to one’s home or homeland, or to one’s family and friends; a sentimental yearning for the happiness of a former place or time: a nostalgia for his college days.

2. something that elicits or displays nostalgia.

—————————

(From dictionary.com)

Noah, you see “nostalgia” as an important theme in the Locas stories, but I see Jaime as using the interplay between various presents and parts of the past to create a more complex effect. As you wrote:

—————————

…in the context of Jaime’s oeuvre, there’s something (eerily?) fitting about Speedy’s disappearance into a darkened silhouette, a kind of icon of himself. Speedy’s a projection, a specter given meaning only by his past. But that’s not just true for Speedy — it’s true for everyone in the Locas stories, who appear and then disappear and then reappear further up or down the timeline. A ghost is a kind of distillation of nostalgia, a memory that walks. At moments like this in Jaime’s work, the compulsive authenticity claims become almost transparent, as everyone and everything turns into its own after-image. We cannot see the present without seeing the past and the future, which means that we don’t ever see anything but an illusion, an image of coherence.

—————————

A fascinatingly more nuanced and interesting perception!

(Though I don’t see that interplay as being an illusion. In a Taoist philosophy class I first heard “There is no past, there is no future. There is only the eternal Now.” Took me a while to get my head around the concept, but afterward — like figuring out “what is the sound of one hand clapping” — it became an obvious perception, which forever altered my view of reality.)

—————————

James, I think even in your comment there’s a pretty strong suggestion that I’m supposed to like it.

—————————

Certainly, when a work gets such overwhelming acclaim, there is — even if not explicitly stated — pressure on folks to feel like they should like it.

—————————

“esp. to the degree that everyone in Locas–readers and characters alike–falls in love with Maggie”

See — not me. I kind of resent the extent to which I’m supposed to fall in love with her, reiterated by the way everyone else throws themselves at her. I don’t dislike her or anything, but she’s not a character I have special affection for or interest in. Like I said, it’s like Bella or Superman in that way; the weight of the emotional response depends on identifying with/desiring a character who I don’t (or not to the extent I’m supposed to, anyway.)

—————————–

Yeah, Maggie’s pretty boring. And as for Hopey’s long-time anarchic zaniness: yawn! (T’was smart, tragic Izzy I really liked; would’ve appreciated as a friend.)

—————————–

I agree with [James] about Calvin for the most part. I wasn’t saying that it wasn’t rape, or that he was to blame. He’s absolutely not to blame; he’s a kid.

Calvin’s being abused. But when he confronts the older boy, he says something like, you promised me I’d be the only one.

…Calvin hates his rapist, but he has other feelings for him as well. That doesn’t make what happens to him not rape. It does show how the rape is accomplished, and why it was so complicatedly traumatic.

—————————–

Unfortunately, if anyone depicts rape or abuse in anything but the most simplistic, clear-cut fashion, includes utterly unacceptable situations such as mixed emotions on the part of the victim, even some pitiful, sick affection for the abuser, that means…you’re “pro rape”! That you’re minimizing the loathsomeness of the victimizer’s actions, saying the victim “was asking for it.”

And, those Stockholm syndrome cases ( http://health.howstuffworks.com/mental-health/mental-disorders/stockholm-syndrome.htm ), all those battered wives who make excuses for, insist they love their victimizers, therefore must not exist.

—————————–

Corey Creekmur says:

The resistance to theory within comics criticism (see decades of The Comics Journal, for instance) is nothing anyone should be proud of …

——————————

(Sarcasm alert) Yes; why anyone shouldn’t bow in reverence before the brilliance of Lacan’s…

——————————

This jubilant assumption of his specular image by the child at the infans stage, still sunk in his motor incapacity and nursling dependence, would seem to exhibit in an exemplary situation the symbolic matrix in which the I is precipitated in a primordial form, before it is objectified in the dialectic of identification with the other, and before language restores to it, in the universal, its function as subject.

——————————

…is incomprehensible! (An observation which Noah’s tidy synopsis shows as a hardly world-shaking perception; inflated, made to appear massively important and “deep” via the deployment of Academese-style gibberish.)

—————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

So you’re rejecting Lacan on the empirical basis of your own experience? How can you do that exactly? Lacan questions specifically the existence of you, and for that matter of “your” experience.

—————————–

Heavens, and this is supposed to be a defense of Lacan? “Lacan says you may not even exist! So, there!”

Which reminds of one section of Tim Kreider’s April 11, 2001 “What Kind of Intelligence Do You Have?” cartoon (in the archives at http://www.thepaincomics.com/), Stoned Intelligence:

Stoner #1: “…But wait a minute, man — if that were true, then it would also mean that you had no existence outside of my mind.”

Stoner #2: [*Phhht*] “Maybe I don’t.”

Heavy, man!

—————————–

Corey Creekmur says:

I didn’t see the use of the term “nostalgia” as derisive, but I didn’t see it getting at what the original term conveys, which is the pain of return, not the pleasure, and Jaime is increasingly a poet of pain…

—————————–

Beautifully put! Even the ending of “The Love Bunglers” is hardly unalloyed cheeriness. Gad, is Ray brain-damaged to a degree? He’s still nice but dwindled, somehow; something pitiable about him…

—————————–

Edgar T says:

Quick note: the phrase “right-of-passage” should be “rite of passage.”

——————————

I’d noticed that; and wondered whether it was a simple typo, or if use of the phrase was accompanied by misunderstanding. Certainly there’s a significant difference between a “right” and a “rite.” As when people say, “given free reign” (when it should be rein), unknowingly altering the original “let your horse run free (while still being able to yank and resume control) to mean “let a king or ruler Do As Thou Wilt”…

—————————–

Allow me to elaborate for readers who don’t know Proust. In scene after scene of In Search of Lost Time, the narrator’s idea of things (the shape that a famous stage actress, or Venice, or a particular bit of architecture has taken in his mind) is continually confronted with the reality of those things, which leads to sometimes crushing moments of disappointment. Where are the pleasures others have described? How can a world that arises in so many convincing, vivid accounts match up with this small, dour, lackluster production?

——————————

Hah! Which actually ties in to the recent “discovery” that the famous madeleine (the cookie whose taste brings back the narrator’s onrush of memories) described by Proust hardly matched actual madeleines:

—————————–

My first batch of the Kamman madeleines came out of the oven smelling great but looking terrible. I picked up one of the misshapen blobs. Not much resemblance to Proust’s “little scallop shell pastry, so richly sensual under its severe, religious fold.”

…Would another recipe yield more Proustian results? Patricia Wells’ fared no better. [Nor did Wells’, or Julia Child’s.]

Things were looking bad for M. Proust…my mind was afflicted with a blasphemous thought: Could Proust’s madeleine ever have existed? Could it be he … made it all up?

——————————

http://www.slate.com/articles/life/food/2005/05/the_way_the_cookie_crumbles.2.html