“All one can say is that that, while civilization remains such that one needs distraction from time to time, “light” literature has its appointed place; also that there is such a thing as sheer skill, or native grace, which may have more survival value than erudition or intellectual power.”

“Good Bad Books” (1945), George Orwell

George Orwell could be pretty cynical as a reviewer but he wrote the lines above with little of that attitude in evidence. His point is somewhat muted by the fact that most of the books he cites (anyone read Max Carrados or Dr. Nikola recently?) have long since faded from memory but we can still see a germ of truth in his essay and this statement.

Some years ago, Kim Thompson approached the entire issue from a more commercial perspective in his essay titled, “More crap is what we need”. The pithy title just about says it all. The article concerns the need for a critical mass of airy but entertaining material to sustain more rarefied and elevated pieces.

Very few would suggest that Mike Carey and Peter Gross’ The Unwritten is possessed of “sheer skill” or “native grace” but one might describe it as a light work with its “appointed place”. Whatever my feelings about the comic, it should be said that it admirably fills the niche sanctioned by Thompson in all his papal authority. While I generally have little time for comics which read like pitches to Hollywood executives, I do recognize their place within that formula which is used to monetize comic franchises. I can easily picture The Unwritten as a Hallmark mini-series – the “high” concept and sly winks at popular culture and general literary knowledge being indispensable selling points in this regard. It is a work which doesn’t so much challenge as lull. Even less can be said of its emotional heft.

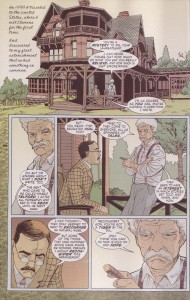

For the most part, Gross’ art on the series serves only to remind us how fortunate Alan Moore was to work with some of the most distinctive artists and craftsmen of his day. There can be little doubt though that the fifth issue of The Unwritten, with its lighter hand and greater attention to detail, represents a kind of high point for Gross. If this issue seems far brighter than the four which preceded it, the glory pertains largely to the artist.

The series as a whole concerns the travails of a certain Tommy Taylor who negotiates the literary landscape of Western civilization while dodging the machinations of a group of bookish conspirators. Taylor is a sort of fully grown, amnesiac Tim Hunter or Harry Potter, all of which has little bearing on the comic at hand which concerns quite specifically Rudyard Kipling’s own interactions with the aforementioned occult group. The story recalls Neil Gaiman and Charles Vess’ take on Shakespeare and the playwright’s bargain with Morpheus in The Sandman. Both series are concerned with the romance of writing and the spinning of stories.

Gaiman has been quoted as saying that stories “are good lies that say true things”. Others have suggested that stories are lies which begin with the truth. The latter statement at least serves quite well to describe this issue of The Unwritten. It is a tale which is best appreciated with a minimal knowledge of Kipling’s life (an easy task in this day and age I should add), for even a cursory acquaintance in this respect is likely to break the spell woven over the course of these 23 pages. This is not to say that the issue at hand is simply a collection of falsehoods. Kipling’s difficulties under his editor, Stephen Wheeler, at the Civil and Military Gazette, as well as his antagonism towards Oscar Wilde and the Aesthetic Movement (“the suburban Toilet-Club school favoured by the late Mr. Oscar Wilde”) are both well documented for example. In fact, a majority of pages are given over to the embellishment of short biographical notes and the illustration of some of Kipling’s most famous poems.

Yet much of the narrative has less to do with historical truth than a selective culling of facts to suit the needs of Carey’s story. To illustrate this, I’ll use an 8 page sequence which marks a turning point in Kipling’s fortunes in the comic.

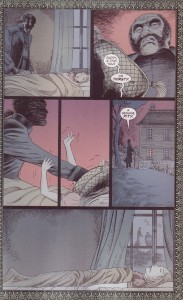

It is 1899 and Kipling is in the United States having a conversation with Samuel Clemens. Kipling is now coming to terms with the Faustian bargain he has made with a cabal of conspirators (a sort of literary Illuminati) who have “an interest in which stories get told, and when, and how.” On divining his complicity and the shallow betrayal of his muse, he tells one of them that he will no longer take instructions from them. Their answer is dread disease and the murder of his child, Josephine.

Kipling returns to England and doesn’t touch a pen for a year. When he does, it is to write one of his Just So Stories, “How the Whale got his throat“, a story which is interpreted as a rapier thrust at his antagonists.

Of course, most of this is just nonsense. In reality, Kipling contracted pneumonia a few days before his daughter’s illness and her death was kept from him by his family and friends. He would not have been by her bedside in her last hours. His reaction to Josephine’s death was not the renunciation of his odes to empire building but the publication of Kim – a book which even a sympathetic biographer like Charles Allen labels the product of his determination to “put out the message that Britain’s imperial mission was under threat – and nowhere more so than in India, cornerstone of the empire…All these fears Ruddy reflected in Kim by making the defence of British India its central political theme, romanticised into the ‘Great Game’..” A considerably less generous view can be found in Edward Said’s famous essay on Kim in Culture and Imperialism (alternative view here). And the response of the bibliomaniacal conglomerate to Kipling’s literary jibes in the Just So Stories? In real life, Kipling won the Nobel Prize in 1907. Not too shabby for someone being targeted by a worldwide conspiracy.

Naturally, it can all be quite easily explained away with some literary sleight of hand. It is, after all, a story set in an alternate universe. Gaiman was smarter when he took on Shakepeare (a little less so in relation to Caesar Augustus especially in the light of Robert Graves), grounding the work fully in fantasy and limiting himself to a few short moments in Shakespeare’s life. Carey set himself a considerably more difficult task by taking on a far better documented life. He also clings far too closely to half-truths and twisted timelines, adding little to the density and mysteries of Kipling’s career.

The real facts of Kipling’s life and work simply do not fit the grand scheme of Carey’s plot. His literary legacy is much more fascinating than anything suggested by this comic, as Orwell makes all too clear in the opening sentences of his essay on the author of The Jungle Book and other children’s classics:

“It is no use pretending that Kipling’s view of life, as a whole, can be accepted or even forgiven by any civilized person. It is no use claiming, for instance, that when Kipling describes a British soldier beating a “nigger” with a cleaning rod in order to get money out of him, he is acting merely as a reporter and does not necessarily approve what he describes. There is not the slightest sign anywhere in Kipling’s work that he disapproves of that kind of conduct – on the contrary, there is a definite strain of sadism in him, over and above the brutality which a writer of that type has to have. Kipling is a jingo imperialist, he is morally insensitive and aesthetically disgusting. It is better to start by admitting that, and then to try to find out why it is that he survives while the refined people who have sniggered at him seem to wear so badly.”

All this while “celebrating” Kipling’s longevity in the minds of the English populace.

What we have in The Unwritten #5 is a skimpy but generally competent abridgment of the author’s life, with little which suggests any heavy lifting on the side of the imagination. The operative word here is “competent” which is all that can be said when fantasy pales in relation to reality. That light literature of this sort should receive unqualified and near universal praise as well as an Eisner nomination is probably only to be expected in the current climate of degraded taste and critical standards.

Pingback: Review – Batman: Dark Knight, Dark City « Patchwork Earth

Wow. Pedantic much?

Think that it’s a little disingenuous to tackle a series that’s all about how “the power of stories” etc to task for not sticking exactly to the truth of things exactly how they occurred. Kipling wasn’t there when she died etc etc: no room for something called: “poetic license”?

Well done you for knowing so much about your history and all that. But your poo-pooing all seems a bit besides the point. Also your “I generally have little time for comics which read like pitches to Hollywood executives” would be way more applicable to lots and lots and lots of other books out there: but not really this one.

If you got off your high horse maybe you’d have a better view of things on the ground maybe?