Every day I plant my seeds on twitter and see what trees will grow. When discussing the ongoing struggle against Time Warner and their child company DC Entertainment, particularly with regards to their campaign of exploitation against Alan Moore, I was chastised for framing the discussion in terms of black and white morality. Specifically, my argument is that all of the participants in the Watchmen project are in fact immoral.

I don’t see why people who are quick to condemn companies as entities shy away from judgement when talking about the men and women who carry out the offending actions. What DC is doing is wrong and the men and women who are working on these projects are wrong for working on the projects. I’ve heard it all about “they have families/mortgages, it’s not their fault” and blah blah blah. Personally, I make thirty thousand dollars per year. Darwyn Cooke is said to have received nearly half a million dollars for his Watchmen miniseries. So we can stop weeping for these poor starving artists who had no choice. Put your violins away.

Most people who know me flinch when I say: Watchmen is the greatest graphic novel of all time. Everybody protests, but my feeling is that they are protesting not the sentiment but rather that “greatest graphic novel of all time” is an answerable quantity. People want it to be unanswerable. Not coldly, flatly answered with “yes, there is a greatest–you read it already, years ago.”

This isn’t to say that better graphic novels aren’t possible in our medium’s future. Just that this book hasn’t been surpassed. Not surpassed in scope, intelligence, craft or cultural effect. Hasn’t been done yet.

Thimble Theatre is a better comic. It isn’t a graphic novel. Maus is important but it isn’t a graphic novel. No novel in comics form–no graphic novel–is greater than Watchmen. You have to deal with that. It isn’t an argument I am interested in having with people. As the greatest graphic novel yet created, it stands shoulder to shoulder with the other great testaments to the power of comics. Thimble Theatre, King Cat and so on. So then, some executives look at their legal documents and say: “yes. Let us add onto this story. That is a legitimate thing to do with a work of art. We shall commission a group of artists and writers to write so many spin-offs that the original work shall be dwarfed. Furthermore, as legal rights-holders we will insist that these new works are a part of the overall text that comprises Watchmen because we can.”

For actual decades, the devotees of this artform have struggled to see this medium treated as a legitimate field. One of the greatest arguments for graphic novels and comics in general as a legitimate creative artform has now been retrofitted as a hot summer crossover event. If art is to have any meaning to human culture then there should be some basic deference to the undisturbed value of the few works that have moved us forward as a people.

I just realized that in our best of poll, Watchmen was in fact the highest rated graphic novel (the selections ahead of it are all strips.)

Good to see Darryl in HU; I hope he comes back soon.

So I’ve basically been avoiding news about Before Watchmen in general but am sort of curious where the information on the half a million dollars pay package came from.

Also, why isn’t Maus a “graphic novel”? Not that I want to read a Eddie Campbell-style dissertation on the subject but I’m interested in why you feel that way.

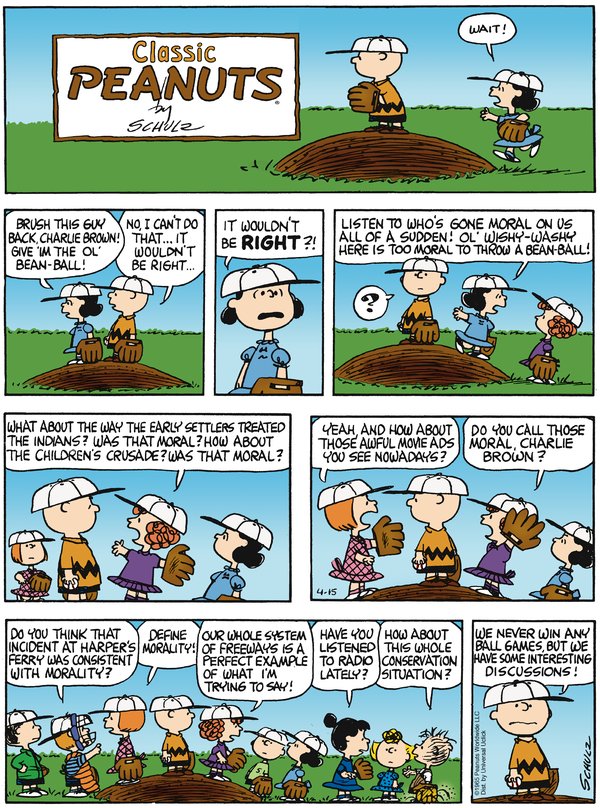

Love the Peanuts strip! Very appropriate to this topic.

These Watchmen prequels seem like a terrible idea. (I’m actually curious about just how bad they will be, even though I don’t want to support the effort financially.) But from a moral standpoint, I’m not quite clear on what a “basic deference to the undisturbed value of the few works that have moved us forward as a people” entails. Do you think, Darryl, that the value of Moore’s graphic novel will be lessened by these adaptations? What kind of deference is appropriate for Watchmen? And who should be the ones to determine this? Works that society has recognized as important or “great” are often adapted, remixed, parodied and picked apart, sometimes horribly or in surprisingly innovative ways that speak to the rich possibilities of the original text and affirm its importance. I think the ethics of DC/Time Warner’s business practices are upsetting to say the least. Still I’m not sure that powerful works like Watchman can/should ever be left alone or policed in a particular way. But again, maybe this is not what you mean by deference.

Just leave the garden alone. Don’t pick the flowers, keep off of the grass and for goodness sake, don’t bring your own seeds to plant.

Just let it be.

I’m also curious why MAUS isn’t a graphic novel!

Qiana, to me there’s a difference between a work that is passionately and to some degree (inevitably) oppositionally engaged with a work (like Moore’s Lost Girls) and a blatant cash grab which (as Darryl suggests) purports to be a continuation of the original work.

So it’s somewhat about motivation; somewhat about marketing; somewhat about aesthetic approach and attitude. The lines are somewhat blurry, but I think they matter.

I’m curious as to why Maus isn’t a graphic novel too, Darryl. Is it because it’s (sort of anyway) nonfiction?

I thought Eddie Campbell had taught us that using “graphic novel” to refer to format rather than subjective artistic worth and intention was yesterday’s game.

Novels are fiction. End of.

“Hey, he drew himself as a wee mousie. It’s fiction.”

– Eddie Campbell

Spiegelman also wrote a letter to the New York Times asking them to remove it from the “Fiction” side of their bestseller list and to the Nonfiction. They complied…

The idea that Watchmen, of all things, is the greatest graphic novel ever is so alien to my experience of art that I find it fascinating. I’ve actually read Watchmen a couple of times to figure out why some people love it so. And while I can recognize the craft and intelligence that went into it, I’m still left with a work that lacks any of the humanity, humor, and depth to be found in the works of Chris Ware, Dan Clowes, J. Hernandez, G. Hernandez, etc. etc.

I do agree that “Before Watchmen” is a gross idea — whatever merit the original had is intrinsic to it being a stand-alone project with a specific set of creators.

Yet and still, /Watchmen/ remains unharmed. At this stage in its young life as a classic (twenty-five years), it remains invincible.

Certainly it isn’t challenged by Ghost World which was a short group of vignettes before Clowes decided to tie it in together, or the sprawling non-novelistic works of both Hernandezes.

I refuse to dignify comics’ attempt to genre-snub important works. /Pulp Fiction/ is one of the defining motion pictures of recent history, but people don’t say “yeah but it is a crime movie.” Nobody says that because it would be silly. Watchmen is easily the definitive classic of graphic novels. Like or not, you basically have to deal with that. It’s the Citizen Kane, Godfather, Pulp Fiction and a bunch of other equivilents.

And it deserves a lot better than to have its legacy second-guessed by everybody from you to Wolverinexx666 on Comic Book Resources.

The best graphic novel yet and no competition on the horizon, really.

“Chris Ware, Dan Clowes, J. Hernandez, G. Hernandez”

Do any of these guys actually express in their art a philosophically, psychologically, politically and historically richer perspective of the world than the works of Alan Moore? I’d like to see that argument, because it seems so clearly wrong. What they do have is more realism, but that’s not much more than an aesthetic bias. (I like them all, though.)

“I refuse to dignify comics’ attempt to genre-snub important works.” I wasn’t snubbing it on genre grounds. I think there have been some really great super-hero comics — by Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Jack Cole, Will Eisner and others. I just don’t think Watchmen is on the level of those works — let alone on the level of Jimmy Corrigan, David Boring, Wilson, The Education of Hopey Glass, etc. Just because a work is sprawling, it doesn’t mean it’s “non-novelistic” — the roman fleuve is by definition a sprawling work — a loose, baggy monster to use Henry James’ phrase.

But… Pulp Fiction is just a crime movie.

I have a feeling that once Chris Ware finishes Rusty Brown, it’s going to win the title of Indisputably Greatest Graphic Novel Ever in the hearts of a lot of people. Even taken alone, the last couple of chapters have been way up there.

“Do any of these guys actually express in their art a philosophically, psychologically, politically and historically richer perspective of the world than the works of Alan Moore?” The short answer is yes. The long answer would require a very long essay or even a short book. But in brief, the political critique of modern America to be found in Lint or The Death Ray seems to me much sharper than the politics of Watchmen. Both Lint and Andy are recognizable and plausible personality types whose character traits reflect dark aspects of the national psyche. That’s one example of many.

I know he didn’t just say “Death Ray” was better than “Watchmen.”

We got nothing to talk about, nothing in common, no language or shared cultural value. Hell no, not in our name, and bring me the head of John the Baptist.

That’s silly and destructive to say. That’s like saying “Truth and Consequences, NM” was a better movie than “Rear Window.” What value is there in just saying outrageous nonsense. It’s like you aren’t even taking comics seriously.

We get it: you like Clowes. But he has yet to touch the hem of Alan Moore’s wizard robe.

Okay; so I’m enjoying the comment thread — Darryl’s last made me crack up. But what I really want here is for Jeet to write a post about why Watchmen is mediocre (ideally for HU, but I’ll settle for it just being written), and for Jack Baney to write me a post about why Rusty Brown is great.

I’m probably doomed to disappointment — Jeet and Jack have spurned my advances before. But I keep trying….

Yeah, I’d go with the Comedian over Lint, just because that’s only a part of the Watchmen, but to each his own. Realism is to narrative like melody to music. I don’t mind it, but don’t require it.

Thanks, Noah, but I’m not a critic. To me, it’s just kind of obvious that Rusty Brown is great.

As for Chris Ware vs Alan Moore, I’d say that while they’re both extremely smart and talented, I probably like Ware a little better because his work is more personal. Some of those Jimmy Corrigan and Rusty Brown/Chalky White strips could only have been created by someone who has experienced extreme degrees of loneliness and self-loathing, whereas Moore doesn’t seem to put much of himself into his stuff. That’s probably an idiotic criterion for art that would put Shakespeare and Nabokov below Charles Bukowski, but like I said, I’m not a critic.

You’re a critic, Jack. A very interesting and funny one too.

I think Moore puts a lot of himself in his work…he’s just a very different person than Ware, I’d say. Loneliness and self-loathing aren’t where he’s coming from, for sure.

You’re a critic, Jack! You’re a wizard, Harry! Alan Moore killed Dumbledore.

But yeah, Noah’s right: autobiographically themed work isn’t necessarily more personal than more convenientional fiction.

BUT: speak to me of Charles Bukowski.

What I’ve read of “Rusty Brown” so far is ok, but inevitably Ware’s thematic concerns are a dead end. What comics needs is a higher ambition of emotional landscapes, not narrow-sliced depictions of pathetic super-hero obsessed nerds. That’s been what Ware has depicted throughout most of his career, sad to say. Based on Ware’s output I’d say alt-comics is not as separated from its super-hero roots as some people like to think. There’s still a lot of growing up to do.

And as far as the idea of the “Greatest Graphic Novel Ever,” I’d say there’s no such animal. There isn’t a single comics long-form work at least in this country that qualifies.

And just to piss of Ayo more, let me say it again- Pulp Fiction is not a great movie, not even a good one. Tarantino might not be propagating fascism, but he is responsible for propogating stupidity and that’s bad enough.

I agree with Darryl on Watchmen’s merits as best graphic novel…even if we include nonfiction, like Maus. I admit to being confused by Jeet’s antagonism toward it. The notion that Eisner, Ditko, or Kirby have produced superhero comics as good strikes me as totally off base… but, y’know, different strokes for different folks, I gues..

I heartily concur; Ayo’s right, Watchmen is indeed a towering edifice in whose shadows others work. May produce admirable stuff, great in many ways, better in some facets, but hardly up to the extraordinary combination of factors that makes Moore and Gibbons’ masterpiece so grand.

I’ve never read anyone object to Watcmen’s status as best gn ever on the basis of genre (though I imagine it’s happened). And while I don’t think it’s mediocre, in fact 8 think it’s pretty great, the notion that it is unquestionably the best graphic novel (defined here as a fiction in words & pictures?) and that to even discuss it is silly betrays an intellectual stinginess I can’t get behind. It also doesn’t speak to the dubious morality of DC or the creators working for it. Would it be OK if the shafting of Moore and Gibbons had taken place but the work was only the fifth best graphic novel of all time?

No, Nate: you’re thinking exactly backwards.

The simple idea that I am trying to convey is that this work is a cultural treasure. DC’s terrible actions are an affront against the creators but also to the single most important work of art within the field.

What I am saying is that this constitutes ANOTHER LAYER OF OFFENSE, not to say it wouldn’t be offensive if Watchmen were less good.

And I’m really disappointed that I have to laboriously repeat myself/restate myself when this should have been right in the text?!

Doesn’t speak to the dubious morality???!!!!???? What article did you–

/resigns/

I understand, but you’re overstating the clarity of your piece. It begins with the question of why we aren’t condemning the creators doing the prequels but moves quickly into a series of statements about the singularity of the original. Sure, these are related ideas, but neither is well served by the lack of development, and I stand by the legitimacy of confusion.

Er, the legitimacy of my confusion… Though confusion is probably legitimate in general?

Man, I apologize for cluttering the comments, but I’m using an unfamiliar machine and my process is all out of whack.

So here’s the thing, I read the piece a little closer and I think I was a bit harsh there. I’m not saying I wouldn’t want to read more, or that I wouldn’t want some more justification for the greatness claims, but as a cry of outrage it’s plenty effective. Sorry to get on your case for not writing an article you never set out to write.

I wish Jeet would explain further…but if I were going to make a case against Watchmen, I’d probably start with the mediocrity of the art. I think Gibbons works really well for Watchmen, and the art doesn’t bother me…but it doesn’t send me, and I think that makes it lose some ground with a lot of people.

I think Jack hits something with the note about personal investment too…Moore’s very steeped in genre, and I think it’s sometimes hard for people to see the ways that that’s personal. Kirby and Ditko are sort of forming the genre Moore is using, so I think people sometimes give them more credit for their genre choices being personal or individual.

So I think that’s probably the brief…not-so-great art; using someone else’s genre conventions. Though there could be other things; I love Watchmen, so figuring out exactly why someone wouldn’t like it is a little tricky.

Even if you don’t like it though…it’s obviously a major, groundbreaking work, vitally important for historical reasons at the very least. Moore’s probably as important to DC’s current output as Jack Kirby is to Marvel’s. That DC is willing to shit on its creator just confirms everything awful you ever thought about the company, and that so many “top” creators are willing to sign on speaks for itself.

It could be counted a failure of HU and comics criticism in general that there has been so little negative criticism (detailed, long form) of Watchmen in recent years. There were attacks on its sanctity early on in its career in the pages of The Comics Journal (I think by Carter Scholz) but very little of worth since then. It’s quite possible that even Maus has sustained more quality negativity over the years.

The best graphic novel ever published is Fabrice Neaud’s

Journal (3). Not to mention something likr Frans Masereel’s Passionate Journal or Charlotte Salomon’s Life? Or Theater?…

The best graphic novel of all time is Kingdom Come: I have spoken, and it is so. The hem of Alan Moore’s wizard robe is not fit to shine the boots of Alex Ross’s portly, middle-aged models — and those boots are already really, really shiny.

Alternatively, the best graphic novel of all time is something published in an obscure dialect of Tagalog in the eighteenth century. Domingos is the only one who’s ever heard of it, and nobody else knows if he’s just made it up or what.

and, actually, I’d go From Hell over Watchmen. Yeah, I’m one of *those* readers. Happily, there’s not much chance of From Hell being adulterated with prequels and sequels. Before From Hell: everyone’s guts were still on the inside.

To be accurate, Watchmen isn’t a graphic novel at all. It’s a trade paperback. It was originally printed as individual comics and reprinted as a collective hole (TPB). A graphic novel is printed originally in a larger (typically complete) story and never as individual issues.

SO CHARLES DICKENS WASN’T A NOVELIST, JASON? SURE THAT MAKES SENSE.

Listen up, buttercup: Watchmen was CONCEIVED as a wholistic and self-contained, self-sufficient and insular longform story. Unlike say Jack Kirby’s Fantastic Four which was conceived as an adventure pulp serial.

What the hell, comic book nerds?! These are simple, obvious things that REAL novels never ever had to contend against. It’s like being in an argument trying to explain, “no really, the earth is round.”

Have you ever even been to a book store? Then you would know that “trade paper back” isn’t a “fat comic,” it’s a general publishing format between Hardcover new release and Mass Market books at the other end.

Ushfhhdskxkfndlkdndsnx!!!!!!!!!!!

————————-

Ng Suat Tong says:

It could be counted a failure of HU and comics criticism in general that there has been so little negative criticism (detailed, long form) of Watchmen in recent years. There were attacks on its sanctity early on in its career in the pages of The Comics Journal (I think by Carter Scholz) but very little of worth since then…

————————–

Couldn’t it be a case that as time went on, the quality of Watchmen became ever more evident, in the way that painters who were razzed by critics of their era for turning in “unfinished” work were eventually recognized across-the-board as brilliant masters?

The use of “sanctity” gives a hint that Watchmen is thought of in some quarters as a “sacred cow.” (Yes, I know that Hindus don’t actually worship cows, but rather revere them, not only for the beneficial products they give — especially milk, and their dung which when dried in as important fuel for fires — but as a symbolic embodiment of the life-giving nature of the Divine, and strive to protect them from any harm. Which actually amusingly ties in with Ayo’s DC, don’t mess with Watchmen, which has contributed so much to the comics art form; “Not surpassed in scope, intelligence, craft or cultural effect.”)

—————————-

Jeet Heer says:

…while I can recognize the craft and intelligence that went into it, I’m still left with a work that lacks any of the humanity, humor, and depth to be found in the works of Chris Ware, Dan Clowes, J. Hernandez, G. Hernandez, etc. etc.

—————————–

“Any of the humanity, humor, and depth…”? While Chris Ware, Dan Clowes, J. Hernandez, G. Hernandez (I’ll skip the etc.’s) indeed have those qualities, Watchmen matches and beats them in all quarters.

When the Hernandezes try to be ultra-serious, their limitations become all too evident. Dan Clowes is a remarkable case; that a Cracked humorist and artist/writer of Lloyd Llewellyn would metamorphose into the creator of The Death Ray and Ice Haven makes the transformation of Dr. Don Blake into Thor seem ho-hum. Ware is mighty fine, though the hermetically-sealed emotional quality of his work (as embodied in the visuals of his “serious” work) is to its detriment.

Alas, compared to the massive, wide-encompassing War and Peace-like scope of Watchmen, their works are miniaturist in comparison. For instance, in The Death Ray Clowes makes many brilliant observations about the dubious morality of superheroes/vigilantes, the mindset of comics fandom, yet the book’s scope is fairly limited.

And gee, in Chalky Brown, Ware (“Stop the presses!”) exposes comics fans as petty, immature, sexually-stunted types. Whatta revelation!

————————–

Jack says:

…As for Chris Ware vs Alan Moore, I’d say that while they’re both extremely smart and talented, I probably like Ware a little better because his work is more personal. Some of those Jimmy Corrigan and Rusty Brown/Chalky White strips could only have been created by someone who has experienced extreme degrees of loneliness and self-loathing…

—————————

“Personal” is good; yet taken to extremes (as Ware does) it becomes navel-gazing; allows one’s constricted, dysfunctionally-distorted view of reality to become the lens through which the world is viewed, thus negatively impacting the work.

Am reminded of how in the relatively-recent movie of “Troy,” the main generals were shown as motivated by cynical realpolitik; because to the modern-minded filmmakers, the idea that military leaders would be concerned with honor and its loss seemed absurd…

I’d be curious to read “anti-Watchmen” criticisms, though I’d expect much to be simply knee-jerk contrarianism, pseudo-elitism (“If it’s so popular, it can’t be any good”), or irritation that it deals with “nonserious, immature” stuff like superheroes.

—————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

…if I were going to make a case against Watchmen, I’d probably start with the mediocrity of the art. I think Gibbons works really well for Watchmen, and the art doesn’t bother me…but it doesn’t send me, and I think that makes it lose some ground with a lot of people.

—————————-

Gibbons is far from one of the greatest comics artists, yet was utterly perfect for Watchmen. Eddie Campbell and Frank Stack are infinitely finer, yet would’ve been completely wrong for the work. On the other extreme, Jack Kirby — though a better “fit” — would’ve been too powerful, broadly sweeping in his approach for the book’s many subtler moments.

Why Gibbons was perfect is shown in one of the book’s motifs: watches and watchmakers. With their status as Watchmen making the characters symbolically akin to the parts of such a timepiece. Gibbons’ precise, rock-solid style would as well suit for rendering an “exploded” drawing of the workings of a watch. (Come to think of it, in one scene Dr. Manhattan is shown having a conversation whilst contemplatively gazing at the workings of a devise he’s mentally disassembled in such a fashion.)

With Gibbons, “diagrammatic” comes to mind: “A plan, sketch, drawing, or outline designed to demonstrate or explain how something works or to clarify the relationship between the parts of a whole.”

Indeed, isn’t interconnectivity, how things are related, from the “thermodynamic miracle” that was Laurie’s very existence, to the possibility at the very end that a pimply doofus in a right-wing magazine might by sheer “chance” explode Ozymandias’ scheme, that a character in a pirate comic book would echo the moral situation of Ozymandias, the main underpinning of the work?

—————————-

Jones, one of the Jones boys says:

…Alternatively, the best graphic novel of all time is something published in an obscure dialect of Tagalog in the eighteenth century. Domingos is the only one who’s ever heard of it, and nobody else knows if he’s just made it up or what.

_________________

Hah! A hit, a very palpable hit!

Steven Samuels. “What comics needs is a higher ambition of emotional landscapes, not narrow-sliced depictions of pathetic super-hero obsessed nerds.” You’re describing one character in “Rusty Brown” — the chapters that have been published give us a much wider cast. Have you read the Lint section? In any case, narrowness in art isn’t a problem if it means going deeper into human experience. The late fiction of Samuel Beckett (from the great trilogy onwards) is very, very narrow — all the action takes place inside some quadrant of Beckett’s mind. But these are great novels and stories because they sound depths that have never been heard before.

@Ayo. “Watchmen was CONCEIVED as a wholistic and self-contained, self-sufficient and insular longform story. Unlike say Jack Kirby’s Fantastic Four which was conceived as an adventure pulp serial.” Your definition of what constitutes a novel. By your definition many of the great novels aren’t really novels — I’m thinking here of Don Quixote (like Ghost World it was originally just a series of short tales stitched together) and most of the fiction of the eighteenth and nineteenth century (often serialized and, as in the case of Thackeray and Trollope featuring recurring characters from fiction to fiction). For that matter John Updike’s Rabbit series weren’t originally conceived of as single work but that’s how they are presented now (in the modern library edition). For that matter Joyce’s stories and novels (including the Wake) feature recurring characters. Any definition of the novel that includes Watchmen but excludes Ulysses is, for me at least, suspect.

@Suat. “There were attacks on its sanctity early on in its career in the pages of The Comics Journal (I think by Carter Scholz) but very little of worth since then. It’s quite possible that even Maus has sustained more quality negativity over the years.”

Yes, Carter Scholz wrote an excellent early critique of Watchmen in TCJ. It’s brief but sums up most of my objections. Which is one reason I don’t feel the need to write my own essay on Watchmen (I might at some point but it’ll be a while before I have enough free time to give the book the attention it deserves for a full-dress critique).

I’ll add that I actually don’t have too much of a problem with Gibbons art. He’s no Kirby or Ditko but his clarity and ability to pack a lot of information into those panels is what the book requires (Moore is very good at choosing his collaborators and tailoring his script to their artistic strengths).

I agree with Jones that “From Hell” is superior to Watchmen — in fact I’d say far superior. Also Moore has done some very interesting short pieces. Moore definately has a place on the comics pantheon but I don’t think Watchmen is the best example of his talents.

Jones: I doubt that many Tagalog graphic novels were published in the 18th century, but you may try the English edition of Elmer by Gerry Alanguilan. I never read it myself, but one never knows. If I understand you correctly you are making fun of me because I have an open mind instead of being provincial like most Americans? How can that be a bad thing?…

Aaaany way, like you I much prefer From Hell to Watchmen.

I was curious, so I started searching to find where that Scholz Watchman review is (#119). I still don’t have my TCJ archive login to see the issue (it is there though), but I found a post where Jeet offers some quotes from it:

http://sanseverything.wordpress.com/2009/03/04/a-watchmen-dissent/

Derik, I just felt something pop in my brain.

It’s clear as day to me that Jeet or whoever he’s quoting simply isn’t willing to engage the work on its own terms. So what good is this analysis. It isn’t any good at all.

To all, especially Jeet: Watchmen is a comic about superheroes like Rear Window is a movie about breaking your leg.

It’s obvious that you’re going to cling to a set of imaginary criteria that exist only to shut out any work that you’re predisposed against. Therefore, there is no talking to you. It’s a novel about human beings. Politics, crime and war. Our foolishness, our attempts at greatness, our rationales for cruelty. Saying that it’s a silly Charlton knock off about sad people is so far afield, you’re not even in the correct stadium.

It is fairly clear to me, a person who really read Watchmen (rather than sort of looking at it) that this book isn’t even trying to be a “superhero comic” and that the theme is not even slightly “superheroes in real life.”

No, “superheroes in real life” is what Daniel Clowes’ ridiculous “The Death Ray” was supposedly about. Which is why THAT remains a minor work while Watchmen in its breadth, scope and mastery of the form remains a timeless classic.

UGH.

Uh oh, are you having an aneurysm?

This whole thing has me wanting to reread Watchmen to see how I feel about it.

Domingos –

“you may try the English edition of Elmer by Gerry Alanguilan. I never read it myself, but one never knows.”

It’s great. You’d hate it.

Unlike you I probably will never know that…

Daryl,

Sure, Watchmen is about a lot more than superheroes, but it’s also a lot about the genre of superhero comics and what it says about about the culture that consumes them (just re-read the newsstand sections and the comics-within-a-comic bits for example). This doesn’t make it a lesser work, but it does make it about superhero comics. Also, and I’m not being disingenuous here, but are you actually mad at us for disagreeing with you? Do you really think we’re dumb nerds? Is there something deeply wrong with me because I too prefer From Hell?

The Scholz quotes are interesting…. I’d say his criticism are ones that Moore intends…the smartest man in the world is meant to be as much a sneer at Adrien as a compliment, and the fact that Adrien is stuck with warmed over sci-fi plots for his masterwork of genius is definitely intentional.

I’d also say that superheroes, and pulp narratives, are a pretty important way in which we think about our geopolitics and our selves. Thinking about the relationship between force and goodness the way Moore does has a lot more breadth and resonance than I think Scholz is giving it credit for.

Still…part of Moore/Gibbon’s point is also that these pulp narratives have serious problems…while at the same time the book is attracted to them. It both rejects and embodies them. I think Scholz’s view is one-sided, but on the book’s own terms I don’t know that it’s unfair. There’s a sense I think in which Moore would have liked Watchmen to end the superhero genre and disappear itself. What’s actually happened — superheroes plodding on, with Watchmen in some ways held up as validating the genre for serious study — is perhaps a more painful outcome than Scholz’s review.

My issue with the reading Scholz and his fellow travelers bring to Watchmen is that they just can’t get past the superhero aspects of it. The deeper theme of Watchmen–and it defines both the form and content–is that one’s experience of life is a Rorschach blot. One doesn’t see things for what they are; one sees what one projects onto them. The book dramatizes how this relates to memory, how people deal with the everyday, the direction people’s lives’ take (including their hold on sanity), and even the course of history. The superhero elements actually enhance the theme because they allow the book to explore it in the more extreme and epic directions. The book is really quite profound, and the resourcefulness and sophistication with which the various story elements are presented and developed is unparalleled in comics.

In terms of reputation, no fiction graphic novel comes close to its stature. Arguing that Watchmen isn’t the preeminent fiction graphic novel in English is like arguing that Kind of Blue isn’t the preeminent jazz album, or that Beloved isn’t the preeminent work of American fiction of the last thirty or so years. One may prefer other efforts more, but these works are the biggest of their fields’ respective big deals.

“I’d go From Hell over Watchmen”

I agree with Jones, as well.

I also love The Death Ray, which is more a snotty dismissal of its genre than Watchmen. In the end, though, it demonstrates that serious themes can be dealt with using superheroes, thereby helping the genre to continue.

@Noah Berlatsky. “I’d also say that superheroes, and pulp narratives, are a pretty important way in which we think about our geopolitics and our selves.”

Yes, that is true and also probably the best argument that can be made on hehalf of the Watchmen. The problem is that politically the book accepts the geopolitical implications of superheroes on their own terms, so the only solution to nuclear Armageddon is the intervention of “the world’s smartest man” and the disappearance of the superhero god. For a professed anarchist, Moore has very little faith in grass-roots political activity. In the real world, the Cold War came to an end because of human agency: Gorbachev and other communists apparatchiks started to see that the regime was untenable, and were pushed for reform by dissidents while in the west Reagan had to start negotiating with the Soviets because of the peace movement. So the real heroes who saved humanity from nuclear war were figures like Solzhenitsyn, Sakharov, Lech Walesa, Gorbachev, E.P.Thompson, Helen Caldicott, etc and the millons of ordinary people on both sides of the Iron curtain who refused to accept the Cold War consensus. There are no counterparts to such figures in Watchmen: humanity’s fate is decided by superheroes (one of whom is willing to sacrifice millions of lives for his political agenda, another of whom is indifferent to humanity’s continued existence). There’s a despair for humanity at the heart of Watchmen which I reject both on political grounds but also because it seems callow and unearned. The darkness of Moore’s vision is ultimately closer to Lovecraft than to Kafka (think of the giant tentacled space monster Ozymandias concocts).

@Ayo. “It’s a novel about human beings.” That’s the core of our disagreement. Despite repeated attempts to enter into it sympathetically, I can’t accept the characters in Watchmen as human beings. Moore has them do all sorts of improbably things (like a woman falling in love with her rapist). They seem like puppets to me. There is also sorts of violence in Watchmen — rapes, murders, and even the killing of millions — but none of effects me as I read the book because none of the characters are able to stake out the emotional claims that are necessary in order for us to care about the fate of fictional creations. Its telling that many readers seem to fantasize about being Rorschach. If the violence Rorschach unleashes had any felt reality, those readers would be terrified of Rorschach and regard him as a psychopath. That’s why I brought up Clowes. He has the ability to create characters that you can both empathize with but also see their flaws and limitations — no one wants to be Andy in The Death Ray, although despite how horrible he is he remains recognizably human. I just don’t see the Moore of Watchmen as being anywhere near the writer Clowes is.

@Robert Stanley Martin. “The book is really quite profound, and the resourcefulness and sophistication with which the various story elements are presented and developed is unparalleled in comics.”

It seems to me that the critique you leveled against Jaime Hernandez applies much more to Watchmen. Watchmen really is a giant Easter egg hunt. Moore is quite clever at packing his narrative with lots of little clues that readers can spend endless hours matching up in order to solve the puzzle. But I find this type of cleverness to be an arid and gimmicky exercise because the story is so utterly devoid of humanity, so utterly contrived and constructed.

And to re-iterate — my objection isn’t that Watchmen is a superhero comic. I have a high regard for the superhero comics of Kirby, Ditko, Eisner, Cole and others. As I noted elsewhere Kirby offers a clue as to what bothers me about Watchemn. In all his comics Kirby created an open universe that could be imaginatively inhabited and colonized. Moore’s genre work, by contrast, seems not just closed by the airtight structures the author has created but even suffocating in the way they don’t allow the characters any freedom from the dictates of the plot and theme. A character like Maggie (in the Locas story) or Andy (in The Death Ray) has the ability to surprise you even as they remain true to their nature. By contrast, Moore’s characters are merely pawns in the service of his agenda.

@Robert Stanley Martin. “In terms of reputation, no fiction graphic novel comes close to its stature.” It really depends on which circles you travel in. I know lots of people that prefer other comics, including other Alan Moore comics.

No one wants to be Andy because he’s treated in a completely condescending manner by the author. I’m not sure anyone wants to be Rorschach, either, but that’s a hard sale to suggest he’s dealt with less humanistically than Andy. Actually, a common criticism of both Ware and Clowes is that they’re completely cold and have nothing but contempt for their characters. I’m not sure I agree, but Moore seems a good deal more sympathetic to the worst of his. Rorschach is a far more emotionally complex character than Andy, who’s not much more than a selfish asshole. And if women can fall in love with Lint, they can fall in love with the Comedian.

@ Charles Reece. “Rorschach is a far more emotionally complex character than Andy, who’s not much more than a selfish asshole.” That’s pretty crude reading of The Death Ray. The middle-aged Andy is pretty much an asshole, albeit one gifted (as many Clowes characters are) in self-justification. But the young Andy was more sympathetically presented — he’s someone in flux, with good traits and bad. The story is about the process where the young Andy starts on the road that turns him into the middle-aged Andy. And Clowes sense of how characters are shaped and formed by their environment seems much more plausible that Moore, who has a crude pop-Freudian understanding of personality formation (i.e. trauma leads to violence). The same applies to Lint — the process by which Lint becomes who he is, the way he’s shaped by his memories and decisions as well as his lifelong traits, is very finely handled. By contrast, Roscharch is just a high-brow version of The Punisher or Wolverine — a psychopath you can root for!

Jeet–

It has that stature with every circle apart from the comics-hipster one that’s centered around TCJ. And that circle’s view of it is so tied up with their Oedipal dramas with Marvel and DC that I don’t take them very seriously about it. Incidentally, I acknowledged that there are people with different preferences. Also, keep in mind that consensus isn’t the same thing as unanimity.

As for Watchmen being more of an Easter-egg experience than Locas, I think it is for you because it’s just more detailed. In general, you seem to have a very hard time distinguishing between the significant and the trivial. An example is your rebuttal of my “Flies on the Ceiling” criticism on the other thread. I think everyone can agree that the Hernandez story is regarded as one of the major highlights of the Locas material. The flies trope is crucial to understanding it. Apart from you, I can’t imagine anyone considers Joyce’s potato motif a major highlight of or crucial to the understanding of Ulysses. To view that detail as anywhere near as significant to Joyce as the flies trope is to Hernandez indicates a total lack of proportion in one’s readings of their works.

I’m not accusing Hugh Kenner of this problem, by the way. He’s making a point about the intricacy of Ulysses, and he deliberately picked a minor detail to make it. He’s not saying or implying that one’s reading of Ulysses is a wash if one doesn’t pick up on it. He calls it “one trivial instance among hundreds of motifs,” after all.

One can treat Watchmen as an Easter egg hunt, but the Easter eggs don’t constitute the armature of the story. They’re parsley, not the steak.

@Robert Stanley Martin. Consensus implies the existence of a coherent comics canon that is widely agreed to (like say the canon of American fiction). I don’t think such a canon exists yet, given the widespread disputes that exist about what is and isn’t a good comics. I don’t dispute that Watchmen is popular and highly regarded by many but I don’t see how that is a convincing argument for its quality. The Transformer movies and the Garfield comic strip are much more popular than Watchmen — are they better than Watchmen?

Since I like some DC and Marvel comics (the works of Ditko, Kirby, etc.) more than I like Watchmen I don’t see how my coldness to Watchmen is a result of an oedipal drama towards DC and Marvel. Where I come from, comics are created by cartoonists, not by corporations.

And to the extent that corporate policies are relevant, I take the side of Moore against DC. In fact, unlike many Watchmen fans, I tend to agree with almost every statement Moore has ever made criticizing corporate comic book companies and the way they mistreat creators.

“Apart from you, I can’t imagine anyone considers Joyce’s potato motif a major highlight of or crucial to the understanding of Ulysses”. This is off topic, but its a characteristic example of your habit of misstating other people’s arguments. I didn’t say the potato motif was important and in fact quoted Kenner as saying it’s a trivial example. My point was that Joyce made even greater demands on readerly attention than Jaime does, but that really isn’t an argument against Joyce (or, by extension, Jaime). For that matter Moore also makes strong demands on his readers attention. The question is, what rewards do you get for such strenuous reading? In the case of Joyce and Jaime, you get a much deeper understanding of human nature and the surface pleasures of life (language, visual forms). In the case of Watchmen, the reward is like the reward for filling out a difficult cross-word puzzle. You feel cleaver and accomplished but are left emotionally unchanged and aesthetically unrewarded. At least that’s my experience.

For the sake of clarity, I should add that I’m not even saying Watchmen is a bad comic. It’s okay — very smart in parts but also flawed. What I object to is the tendency to regard it as the greatest graphic novel of all time. There’s much better work out there and its sad to see people settle for a middle-range work when comics can be so much more.

Too bad because Watchmen still remains untarnished even by your halfhearted prosecution.

It’s interesting that 98% of the discussion pro and con is centered on Moore’s script, and so little on the visual side. Part of the reason I personally prefer From Hell is that I prefer Campbell’s work there to Gibbons’ work on Watchmen, by a considerable margin (although Gibbons is good, too).

But no one gives a shit about John Higgins’ colours, apparently. (Including me — I had to look it up)

Well, as I said before, I think Gibbons’ art is actually good for the story, so the work stands or falls by the writing. One of Moore’s strength is that he does (unlike most comic book scripters) try to match his writing to the art (and it’s hard in a Moore comic to separate story and art because he and the artists spend a lot of time talking together).

I thought the colours were fairly middling as well — not great but suitable to the story.

On the visuals, I should add that one reason I rate Kirby, Ditko etc. so high is that these were very imaginative artists and vivid picture makers. However absurd a superhero story might be, if it’s illustrated by Jack Kirby it at least will keep your eyes very happy.

Also, I should add that Eddie Campbell is, as Jones says, the Moore collaborator who brings the most to the table. So maybe, despite what I wrote above, the visuals are part of the story in my lukewarm response to Watchmen.

Jeet: “However absurd a superhero story might be, if it’s illustrated by Jack Kirby it at least will keep your eyes very happy.”

What a shallow reason to rate anything high.

Jeet–

Oh, we have a canon. The Comics Poll top ten is a pretty good reflection of it. Looking back on the various discussions of comics over the last several years, those comics are pretty much what one would come away with. They’re not fixed, but canons never are. Claiming there isn’t a canon just seems another way of avoiding acknowledgement of Watchmen’s stature, at least in part.

I was being snotty with that Oedipal drama crack, although I do think it’s applicable to a number of people in the TCJ circle. Wanting to kill Marvel in order to marry Jack Kirby is a fairly apt metaphor for some of the attitudes on display. But away from that, it’s pretty much an article of faith that the hegemony of the superhero genre must be destroyed in order for comics to realize itself as an artform. Any work that’s perceived as reinforcing that hegemony is going to be treated very harshly and even unfairly.

With regard to Joyce, if your point is that he makes greater demands on a reader’s attention but towards trivial ends that aren’t central to an understanding of his work, then why are you bringing it up in the first place? I’m not complaining that Jaime features Easter eggs in his work. I’m complaining that he’s building his major effects out of them. Joyce isn’t doing that. Neither are Moore & Gibbons for that matter. The Easter eggs in Ulysses and Watchmen are tertiary; they’re decorative.

In other words, if the potato motif isn’t an example of how Joyce’s demands on the reader provide a “much deeper understanding of human nature and the surface pleasures of life,” give me an example from his work. Argue the point with a relevant example, not an irrelevant one like the potato motif.

@Domingos Isabelinho. “What a shallow reason to rate anything high.” Yeah, God knows when we’re dealing with a visual art form we shouldn’t care if the art is visually pleasing. Perhaps in Domingos’ world art has to punish and hurt. Are you a secret masochist?

Robert –

“It has that stature with every circle apart from the comics-hipster one that’s centered around TCJ.”

Actually, if there’s anything the blowback to Moore’s antagonism toward superhero publishing has revealed, it’s that plenty of devoted superhero readers don’t rank Watchmen much at all. I suppose they ‘recognize’ its stature, but mainly as a millstone, a construct of an outside media prone to simplifications, or as the result of over-enthusiasm by set-in-their-ways readers or dilettantes. You’re frankly more likely to hear All Star Superman named — or yes, good ol’ Kingdom Come — or even something by a newer writer like Jonathan Hickman or Jason Aaron. I don’t think there’s ANY consensus right now in really active superhero circles.

“For a professed anarchist, Moore has very little faith in grass-roots political activity. In the real world, the Cold War came to an end because of human agency: Gorbachev and other communists apparatchiks started to see that the regime was untenable, and were pushed for reform by dissidents while in the west Reagan had to start negotiating with the Soviets because of the peace movement….There’s a despair for humanity at the heart of Watchmen which I reject both on political grounds but also because it seems callow and unearned. The darkness of Moore’s vision is ultimately closer to Lovecraft than to Kafka (think of the giant tentacled space monster Ozymandias concocts). ”

That’s a really great critique of Watchmen. I still think you’re missing some of the distance Moore has on his tropes…Ozymandias doesn’t actually save the world, for example — I think you can read the book pretty easily as coming from the perspective you are (viz. power is not a force for good.) The Lovecraft monster is supposed to be idiotic, as is Ozymandias himself.

At the same time, like I said before…it’s a tension in the work, and I think it’s valid to feel he doesn’t manage to resolve it. It’s certainly given me something to think about in the comic that I hadn’t put in quite those terms before.

Jeet did you read Katherine Wirick’s piece on Rorschach as a rape victim? It’s here. I’d be curious what you think about it.

“if there’s anything the blowback to Moore’s antagonism toward superhero publishing has revealed”

It’s also revealed that lots of superhero fans are total fucking arseholes…but that’s probably only a revelation if you’ve never read any of the comments on any “mainstream” site, ever.

That said, how much of the blowback comes from independent scepticism about Watchmen, rather than general reaction-formation to the implication that you’re a douchebag for wanting to buy Watchmen Babies? You see the same reaction to the Kirby suit, the Shuster suit, etc etc. every time one of the people who make the things gets too uppity. “I like The Avengers/Watchmen/Superman, but their creators can go suck a dick”.

Jeet: Let’s put it this way: If the story is stupid the drawings are stupid, period.

I know where you are coming from though: important philosophical things are the realm of words. The visual arts just need to be pleasing because images can’t be anything else.

“I know where you are coming from though: important philosophical things are the realm of words. The visual arts just need to be pleasing because images can’t be anything else.” No, I don’t think that. I’m actually close to the position that Charles Hatfield articulates in his Kirby book, that comics are a form of narrative drawing. But having said that, there are situations where the story can be fairly conventional or worthless but the drawings have a life of their own — in part because art has its own values that are distinct from articulated verbal ideas.

@Robert Stanley Martin. “Oh, we have a canon. The Comics Poll top ten is a pretty good reflection of it.” I’ll simply echo Jog and say that even among superhero fans there’s no fixed canon that would automatically rank Watchmen high.

The poll you conducted was fun and instructive but an internet poll isn’t a canon. You can find internet polls where “Atlas Shurgged” is ranked as one of the modern works of literature.

@Robert Stanley Martin. “I’m not complaining that Jaime features Easter eggs in his work. I’m complaining that he’s building his major effects out of them. Joyce isn’t doing that.” Look, the major effect that Joyce achieves is the creation of characters like Stephen Dedalus, Leopold Bloom, Molly Bloom and others. These characters have a substantiality rare in fiction because of thousands of little characterizing motifs that Joyce has embedded in his novel, of which the now-infamous potato is one trivial example of many. Just the same the major effect Jaime achieves is the creation of characters like Maggie, Hope, Penny, etc. These characters are made substantial through thousands of little details, of the kind you complain about. With both Joyce and Jaime, you can appreciate the main features of the characters (such as Leopold’s kindness or Maggie’s indecisiveness) without necessarily catching all or even most of the embedded details. This is not to say that Jaime is as great as Joyce but simply to note that there is a similar procedure at work. So your complaint that Jaime makes extravagant demands on his reader’s attention is not very convincing.

There is a striking difference here, by the way, between Moore’s easter eggs and the easter eggs of Joyce and Jaime. The two J’s use their easter eggs to enrich our sense of place and character. Most of Moore’s easter eggs (i.e. the watch images throughout the book) are merely displays of authorial cleverness.

————————–

Jeet Heer says:

…narrowness in art isn’t a problem if it means going deeper into human experience. The late fiction of Samuel Beckett (from the great trilogy onwards) is very, very narrow — all the action takes place inside some quadrant of Beckett’s mind. But these are great novels and stories because they sound depths that have never been heard before.

—————————

But, are they greater than comparatively-fine novels which encompass a wider range of human experience?

—————————-

…I agree with Jones that “From Hell” is superior to Watchmen — in fact I’d say far superior.

—————————–

A reasonable argument; I’d rate it as just below Watchmen, m’self.

——————————-

Domingos Isabelinho says:

Jones: I doubt that many Tagalog graphic novels were published in the 18th century, but you may try the English edition of Elmer by Gerry Alanguilan. I never read it myself, but one never knows.

———————————

I’ve not finished reading my copy (the last few months have been highly chaotic), but it’s extremely fine so far…

———————————

If I understand you correctly you are making fun of me because I have an open mind instead of being provincial like most Americans? How can that be a bad thing?…

———————————-

It’s just such a predictably Domingos-esque reaction to hold up some utterly obscure foreign work as the highest masterpieces out there.

You may very well be right, for all we know. After all, in “Old Wine in New Wineskins: Hisashi Sakaguchi’s Ikkyu” ( https://hoodedutilitarian.com/2012/04/old-wine-in-new-wineskins-hisashi-sakaguchis-ikkyu/ ) Ng Suat Tong (and the art sample pages) sure make that relatively-obscure work come across as a towering masterpiece…

——————————–

Nate says:

Daryl,

Sure, Watchmen is about a lot more than superheroes, but it’s also a lot about the genre of superhero comics and what it says about about the culture that consumes them (just re-read the newsstand sections and the comics-within-a-comic bits for example). This doesn’t make it a lesser work, but it does make it about superhero comics.

———————————

But, not just “about superhero comics.” It uses the genre as a vehicle to comment on far weightier subjects. Life; the human condition; our attempts to wrest the universe into shape and the mental distortions that result; morality; what constitutes heroism; “to create four or five ‘radically opposing ways’ to perceive the world and to give readers of the story the privilege of determining which one was most morally comprehensible” (Alan Moore’s intention, mentioned in http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watchmen ).

——————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

…I’d also say that superheroes, and pulp narratives, are a pretty important way in which we think about our geopolitics and our selves.

——————————-

Lord, yes. Consider Ronnie Reagan, god of the GOP, referring to the U.S.S.R. as an “evil empire”; calling his utter B.S. anti-missile system “Star Wars”…

——————————–

Robert Stanley Martin says:

…The deeper theme of Watchmen–and it defines both the form and content–is that one’s experience of life is a Rorschach blot. One doesn’t see things for what they are; one sees what one projects onto them. The book dramatizes how this relates to memory, how people deal with the everyday, the direction people’s lives’ take (including their hold on sanity), and even the course of history. The superhero elements actually enhance the theme because they allow the book to explore it in the more extreme and epic directions. The book is really quite profound, and the resourcefulness and sophistication with which the various story elements are presented and developed is unparalleled in comics.

———————————

Bravo! Perceptive and superbly put…

———————————

Jeet Heer says:

…So the real heroes who saved humanity from nuclear war were figures like Solzhenitsyn, Sakharov, Lech Walesa, Gorbachev, E.P.Thompson, Helen Caldicott, etc and the millons of ordinary people on both sides of the Iron curtain who refused to accept the Cold War consensus. There are no counterparts to such figures in Watchmen: humanity’s fate is decided by superheroes (one of whom is willing to sacrifice millions of lives for his political agenda, another of whom is indifferent to humanity’s continued existence). There’s a despair for humanity at the heart of Watchmen which I reject both on political grounds but also because it seems callow and unearned.

————————————

But, not just “despair for humanity”; there are plenty of examples of humble, noncostumed humans, who are shown as moral, caring, striving to do the right thing, for all their final fate. The cops and psychiatrist who as their last act moved to stop the fight of the lesbian couple. The way the salt-of-the-earth newsstand vendor, as death moved to overwhelm the city of New York, protectively embraced the black kid who’d been hanging out reading this pirate comic. As their bodies merged and dissolved, tears came to my eyes…

——————————–

The darkness of Moore’s vision is ultimately closer to Lovecraft than to Kafka (think of the giant tentacled space monster Ozymandias concocts).

——————————–

Hah! Great perception…

———————————

…Despite repeated attempts to enter into it sympathetically, I can’t accept the characters in Watchmen as human beings.

———————————

You’re entitled to; I’ve no trouble seeing them as that.

———————————-

Moore has them do all sorts of improbably things (like a woman falling in love with her rapist). They seem like puppets to me.

———————————-

Humans routinely do things so utterly insane (let’s dump our industrial toxins in the water we drink, air we breathe; let’s us lower-class folks vote into office the exact people who see us as cattle to be exploited and devoured); that “a woman falling in love with her rapist” is not much of a stretch in comparison.

Re that “puppets” line, Dr. Manhattan says (quoting from memory) “We’re all puppets. I’m just one who can see the strings.”

———————————

Its telling that many readers seem to fantasize about being Rorschach. If the violence Rorschach unleashes had any felt reality, those readers would be terrified of Rorschach and regard him as a psychopath.

———————————-

It’s telling that when you want to knock the literary worth of Watchmen, you use the asinine reaction of dimwits to “prove” the book is shallow.

Jones – I’m sure that’s some of it, though there’s also a likely encouragement effect at work, in that superhero readers who didn’t much care for Watchmen see more opportunity for expressing those opinions; I mean, that fucking movie put the book into as much of a spotlight as the current situation.

But anyway, I was just contesting Robert’s point as to the existence of circles that affirm Watchmen’s stature (though obviously I haven’t taken a poll or anything, this is anecdotal; I recall Wizard doing a list of Top 100 Trade Paperbacks years ago that put Watchmen at #2 behind Maus, although I think that was editorially-driven)…

@Noah. “Jeet did you read Katherine Wirick’s piece on Rorschach as a rape victim?” I was just looking at it before you posted. It’s a very smart piece. This is not meant as a knock on Wirick (who makes a convincing case for how Rorschach should be interpreted) but I’m wary of accounts of fascism that start with the victimization of fascists. To the extent that fascists are victims or losers, its because they’ve benefited from systems of privilege (capitalism, imperialism, patriarchy, imperialism, racism) which are being challenged.

Jeet: I don’t know why comics must be narrative at all, or why words are excluded from the narration when it exists (which is clearly absurd), but let’s pretend that you and Charles Hatfield are right and comics are “a form of narrative drawing.” In that case, if the story is dead serious and stupid what are the drawings telling it? Genius incarnated?

@ Mike Hunter. “there are plenty of examples of humble, noncostumed humans, who are shown as moral, caring, striving to do the right thing, for all their final fate. The cops and psychiatrist who as their last act moved to stop the fight of the lesbian couple. The way the salt-of-the-earth newsstand vendor, as death moved to overwhelm the city of New York, protectively embraced the black kid who’d been hanging out reading this pirate comic. As their bodies merged and dissolved, tears came to my eyes…”

True, but all of these are defensive and futile gestures in the face of a world controlled by costumed gods. Non-superheroes in Moore’s universe can try (unsuccessfully) to defend themselves but they can’t make their own history or challenge the power that be. In the real world, thankfully, ordinary people can and do stand up to tyranny, even if they are often defeated.

Also, if we take the deaths in Watchmen seriously we should regard Ozymandias as a moral monster, a veritable Eichmann. Yet even after the extent of Ozymandias’ actions are revealed, he’s treated not as a moral monster but rather as a pulp figure, a superhero-who-turns-out-to-be-supervillian. His plot is so outlandish that we can’t treat it seriously and feel the full moral import of his actions.

@Domingos Isabelinho. The comics I love are the ones where the writing and drawing are perfectly integrated. Ideally all comics would be integrated in that way, but we live in a less than ideal world, so there are plenty of examples of bad stories that are well drawn (many of the EC comics stories fall into this camp) or (less frequently) good stories poorly drawn (in the later category I’d mention some of Pekar’s work that was drawn by mediocre artists). I’m not sure why this is so shocking to you. Sometimes art and story don’t align perfectly. It’s regrettable but it happens.

I think Moore makes some effort — which I found effective — to show Adrien as a moral monster. He very carefully has you get to know many of the non super powered people in New York; the lesbian couple, Rorschach’s shrink, the newspaperman and the comic reading kid. Unlike in a regular superhero plot, you know the people who die — which is definitely a critique of the genre.

I think Ozymandias’ plot, in all its stupid genre glory, is also meant to be a comment on the way that such schemes of conquest and saving the world (invading Iraq?) are intrinsically idiotic. To me that doesn’t make their victims less tragic; quite the contrary.

I still think the point that only the superheroes get to act effectively is a really good one. I think I’d respond by saying that part of what Moore’s doing is playing with the notion that superheroes are in fact superior. It’s absolutely not clear that they are…Rorschach’s death, where he goes back to being Kovacs, is of particular interest maybe.

Jeet: nothing of what you say above is shocking to me in the least. What’s shocking is how easily a stupid story is rated high in the comics milieu. I say “comics milieu” because you’re not alone, I am.

Jeet, is this a problem you have with other dystopias? 1984, for example?

One of the worst crimes of the movie is that it removed the mechanicals, so there’s no one left to represent real humanity (although how could they feasibly have included them?). Just one more way to turn it into a boring, normal superhero story about people punching one another.

@Domingos Isabelinho. “What’s shocking is how easily a stupid story is rated high in the comics milieu.” But the story is not being rated high — the story and art are being dissociated from each other, with the story being rejected as stupid while value is found in art. To take this outside of comics — haven’t you ever seen a movie that has a poor script but some good acting or cinematography? Or a good script and generally poor acting? In a collaborative work of art, not every element always works together.

Comics don’t have to be narrative but they are much better when they are. I don’t believe in the validity of non-narrative because we humans are a storytelling kind. Even those “tone poem” comics (whatever that means) tell a story.

Whatever. You are clearly chomping at the bit to talk about some theoretically-possible comic that frankly nobody in the world cares about or believes in except you.

You cannot appreciate art because you are always searching for some imaginary “better.” Like some guy who is talking to a beautiful woman at a bar but keeps glancing over her shoulder just in case a more beautiful woman happens to be around. Meanwhile you are about to get dumped because HELLO, you’re on a date with this one!

You never have a whole lot of affirmative things to say, only theoretical “possible” “better comics.” Show and prove. Put up or shut up. You can’t back up the stuf that you say so you change the topic to your favorite nonsense about “fascism” or whatever. You have no ideas. Your scant writings betray a woeful ignorance and close-minded disregard for anything that another person may have heard of–simply because you are so arrogant that you cannot live with the notion that good art probably isn’t difficult, obscure stuff. Or else probably more people would have heard of it.

LOOK WATCH THE MAN TRY AND INTERPRET THAT LIKE I SAID POPULARITY EQUALS LEGITIMACY. HE WILL TOTALLY TRY THAT.

Face it, if the stuff you liked was any good, you wouldn’t have been the only person to have heard of it. All of us are hungry for comics. All of us. We’d be all over your ideas if they had any merit or connection with reality.

Watchmen forever. Death to Moroccan tone poems.

What the hell, I’ll join in too. I completely disagree with Jeet’s reading of Watchmen. I think he misses several key points (I totally regarded Viedt as a monster, and say the book as a total condemnation of the idea that the world “needs saving” from humanity). The book was a keystone in my comics reading as a young lad, so I have a very nostalgic soft spot for it, and I return to it often.

That being said, I don’t think it would make my person top 10 favorite books right now. And I think “From Hell” is a much better, richer book and Moore’s best work to date.

@Noah. “Jeet, is this a problem you have with other dystopias? 1984, for example?” Well, in 1984 Winston Smith and Julia do resist the totalitarian state. They are ultimately defeated and brainwashed (in a horrifying way) but despite the defeat the book hinges on the idea that there will be some internal resistance. There’s on resistance in the world of the Watchmen, only futile attempts to save a few lives in the fallout from the actions of the superheroes — but no attempt to change the system whereby the superheroes dominate or the geopolitics the superheroes are embedded in and support.

@Noah Berlatsky. “I think Moore makes some effort — which I found effective — to show Adrien as a moral monster. He very carefully has you get to know many of the non super powered people in New York; the lesbian couple, Rorschach’s shrink, the newspaperman and the comic reading kid.” It’s fairly common in movies to spend a few moments with sympathetic figure — say a cop who is about to retire — who is then killed. This is done to establish some moral gravitas or emotional engagement on the cheap. In terms of narrative, these characters are created in order to be killed. That is what Moore is doing — being talented he does it well, but it’s still a relatively cheap effect.

Darryl, man — I love you…but there’s just no need to get that nasty.

Domingos writes positive pieces just about every month here. He talks about tons of specific comics he likes. Different things than you like, and different things again than Jeet likes, but that’s not a disaster.

Also…there are definitely folks who like the kind of comics Domingos does; even some other writers on this blog. He’s certainly in the minority…but Fabrice Neaud, who he mentioned, is held in high regard by a lot of people. He’s not nearly as isolated as you’re making him out to be.

Jeet: I understand your point up to a point, but you’re the one who rated Kirby’s art in a stupid superhero story high because it’s “enjoyable,” not because it has something important to say. Then you associated the art and the story when you characterized comics as “a form of narrative drawing.” The drawings are narrating a stupid story and yet, they’re rated high?

Now you want to dissociate the drawings from the story again because the story is stupid, but you still want to rate Kirby’s art high.

Sorry, but I smell a sacred cow… Maybe I even smell the king of all sacred cows.

@Ayo. I’m sorry for hijacking your post like this, especially since I think that despite my ambivalence about Watchmen we can agree on some major points: 1) Watchmen is a hugely important graphic novel which looms over the field of comics. 2) Watchmen deserves to preserve its status as a stand-alone work. 3) The current “Before Watchmen” project deserves to be condemned as an assault on the integrity of this important work. Can we agree to sign off on this statement?

@Domingos Isabelinho. As so often, I feel like I’m not making myself clear to you. I’m not saying that a stupid story illustrated by Jack Kirby is necessarily a great thing, just that it will at least be visually entertaining, which is no small thing. By describing comics as narrative drawing I meant that at their best the art and storytelling are integrated in comics — as they are in the Jack Kirby work I like best, the 1970s work. (By the way, this is my spin on Hatfield’s concept and Hatfield shouldn’t be held responsible for it). Some of those stories are very well written — which is what deserves to be celebrated. Some of those stories are just silly, but again even in that case Kirby’s art redeems the material to some degree.

I think our misunderstanding comes from the fact that you think about art in a binary way. A work of art is either good or bad, a masterpiece or kitsch. I think there are a few good works of art, and many bad works of art but also a sizable category of mixed works, that have both good and bad qualities. You don’t seem to be able to accept the existence of this category of mixed works — everything to you is either good or bad.

@Robert Stanley Martin. “Wanting to kill Marvel in order to marry Jack Kirby is a fairly apt metaphor for some of the attitudes on display.” This oedipal analogy only makes sense if I thought that Marvel was the co-creator of Kirby’s comics. But as I said before, I don’t think corporations create comics, cartoonists do. Pace the Supreme Court and Mitt Romney, corporations aren’t people. They are legal entities (which sometimes have bad policies which should be challenged, just as legal entities like churches or the courts do). In any case, why would an oedipal complex make me more sympathetic to one creator who was screwed by corporate policy (Kirby) but less sympathetic to another creator screwed by corporate policy (Moore). Actually, I’m sympathetic to both, but just happen to like Kirby’s work more.

Jeet: If you don’t start writing that Watchmen essay soon, someone might steal your comments here and put them up on HU. And I agree with Noah re: your dissection of the politics of Watchmen.

Well I can offer a conditional partial retraction. But I’ll be damned if the man’s entire shtick isn’t:

-walk into a room

-call everything childish

-make vague reference to esoteric obscure something

-????!

-repeat

Sure it’s one person’s opinion, but if he feels that he’s got to tell everyone else what plebes we are in expressing it then my response is (1) don’t believe his opinion can stand on its own and (2) disinclined to take it seriously or devote serious attention to.

All of what i have seen the man write indicates a narrow view on art and “the arts” which offends me to the core. Right now he’s dumping on Kirby, from what I see in my email alert. I’m like–really?

And then there is his nonsense where he doesn’t understand that it’s okay to like a comic in pieces. Again, with his anti-Kirby chatter. Maybe he really genuinely doesn’t understand what everybody else appreciates about Kirby but that doesn’t mean he has a vital perspective, it means he should study more. Like I did. Like many of us did.

He talks a mean one about artistic sophistication but his words betray a man unwilling to do the work.

I mouth off a lot but I study a lot. I know my stuff inside and out. I don’t believe he does.

@Chris Mautner. Your reading of the book is closer to the majority one, so I’ll have to accept the fact that there is just something about it that I’m misreading or misunderstanding (despite repeated efforts to enter into the book sympathetically).

One point. “(I totally regarded Viedt as a monster, and say the book as a total condemnation of the idea that the world “needs saving” from humanity).” The thing is, in the context of the book Viedt is cool in the way that Rorschach is cool. Viedt has a secret hide-away, just like Superman! He’s the smartest man in the world and a gifted inventor, just like Lex Luthor! He’s always one step ahead of the game, just like the Kingpin or Dr. Doom! So as you read about his plot, Viedt doesn’t seem like Eichmann or Beria or Pol Pot. He seems like Dr. Doom or Magneto. So it’s hard to take his crime or moral culpability seriously. Or at least I can’t take it seriously. His murders don’t seem real. (By contrast, the killings in The Death Ray are chillingly believable).

@Suat. Feel free to steal these points!

Jeet: I’ll make a final effort to understand you: you rate high something that’s not necessarily a great thing?

The notion that Moore has no time for “ordinary people” or grassroots politics seems wrongheaded to me. The whole point of the book, or one of its central arms at any rate, is the critique of ordinary people who allow the “super powers” (political in the real world, superheroes as well in the Watchmen world) to think and make their decisions for them. As in V for Vendetta, Moore tries to push all of us to take responsibility for ourselves, to not accept or allow those with “power” (superheroes are just a metaphor for this) to make decisions for us, etc. That’s the whole gist of the “Who Watches the Watchmen” motif. Moore is a self-professed anarchist, which (as he often says) means, simplistically, “no rulers.” As such, Watchmen is an anti-superhero book…but more than this it’s an anti-government, anti-ruling powers, pro-“ordinary person” book. That is, it pushes quite hard for us to take responsibility for our own lives, to care for others (like Bernie/Bernard, Dan/Laurie, Dr. Long at the close of the book) without being paternalistic and condescending (like Veidt), etc. The “ordinary people” on the street are not just some dude humanized for 5 minutes and then wiped out (as in many a movie). They’re human beings we get to know month-by-month over the course of a year (esp. if you read it in its original installments). When they die, you feel it, precisely because they were never that kind of simplistically constructed sidebar. It’s true that they never effectively resist power (except, perhaps, unwittingly, Seymour in the final panel), but part of the way in which the book works is to turn these questions out towards the reader. The world, and its future, is “in our hands” in the final panel…not really in Seymour’s, since his world doesn’t actually exist. As in V for Vendetta, the book is largely about the necessity and possibility of “grass roots” changes by ordinary individuals and the toppling of those in power. The transformation of society into a more egalitarian one is certainly at stake here, though it never actually happens within the pages of the book. The books (both V and Watchmen) do maintain a healthy skepticism about human nature (it’s worth pointing out that things in the ex-Soviet Union and the U.S. are hardly perfect as a result of the end of the Cold War), but they do certainly propose that we take control of our own destinies, instead of abdicating power to our “rulers.”

If there’s a critique in this regard, I would say it’s not in the sense that the superheroes hold all the “real” power in the book (on the contrary…they are just as flawed as the rest of us…and their most dramatic actions are just as susceptible to undoing by dopes like Seymour or by sheer dumb luck). Rather, the preoccupation with 4D temporality and Einsteinian physics suggests agency itself may be a perspective illusion…which would, of course, serve to undercut any notions of grassroots politics and weakens those aspects of the book (though, to me, anyway, it makes it more interesting philosophically)

In terms of Jeet’s critique, though, I would say that the heavily emphasized humanity of the superheroes themselves (their many failings), and esp. the emphasis on Ozy’s hubris and general stupidity, all suggest that the “important doings” are actually NOT undertaken by superheroes any more than by the rest of us…

Finally, I think it’s the height of nonsense to suggest that Moore’s/Gibbons’ characters are somehow less human and accessible than those of Clowes, or the Hernandezes, or whatever. Dreiberg and Laurie are way more accessible,human, complex and ordinary figures than Andy in The Death Ray, just as one example. Veidt is a fairly flat character (we know so little of his origins), but Rorschach, Dreiberg, Laurie, Blake, Sally… These come across as living, breathing folks…as do Dr. Long, Hollis Mason, and (at times) Bernie the newsstand guy, the lesbian taxi driver, etc. Some only have their moments…but most are well-rounded complex characters who we certainly can empathize with.

I think that having Sally forgive her rapist might be seen as a political misstep from a feminist point-of-view, but I don’t think it makes her less believable.

Ayo, have you read Domingos’ blog? It’s over here, and it really is mostly him talking about things he likes.