“There is no enemy so cruel or so ruthless as a once-defeated criminal who seeks revenge.” With this typically portentous opening sentence, William Moulton Marston lets us know that we can expect to see a few familiar villainous faces over the course of Wonder Woman #28. And sure enough, the story makes enjoyable use of a device that has since become a cliché of the genre: the super-villain team-up. But Marston’s resort to this now standard trick from the hack-writer’s grab bag was probably prompted by something more than the ordinary motivations of a professional comic-book scribe. Having recently received a fatal diagnosis of cancer, he knew he faced the ultimate deadline, and that this story would likely be his swan song. Whereas the standard comic book “blast from the past” is an opportunity to say hello, again, to members of the rogue’s gallery that we have come to know and love, Marston was saying goodbye. Wonder Woman #28 is his fond farewell, then, not only to the character that had finally brought him fortune and fame, after a long search for the spotlight, but also to her entire supporting cast.

Writers such as Ken Alder, Geoffrey Bunn, Les Daniels, and Gerard Jones, among others, have provided a wealth of information regarding Marston’s career prior to the creation of Wonder Woman. Consequently, we now know that Marston’s various previous attempts to convert his academic credentials into money and celebrity had met with a measure of success, but had not provided him with a platform on the scale of his dreams, let alone financial security. From his earliest correspondence with pioneer publisher M. C. Gaines, however, Marston seems to have grasped both the commercial and communicative potential of comic books — seeing possibilities for both profit and proselytizing in a new medium that most members of his generation and class could only dismiss with disdain. His faith proved well placed. He scored big on his first try-out, creating one of the most immediately recognizable and indelible images of female empowerment to emerge from the mass-cultural milieu of 20th century America. But Wonder Woman was no mere lucky strike, or the product of a sudden epiphany. On the contrary, she was in many ways the culmination of more than twenty years of sustained intellectual work on Marston’s part — the comic book incarnation of half a lifetime’s meditation on the subjects of human psychology and sexuality.

Inspired by and at some level perhaps even a partial composite of Elizabeth Marston and Olive Byrne, the two real women with whom Marston lived in a polyamorous relationship, Wonder Woman was without doubt conceived as part of a sincerely feminist vision (which is one reason why she can claim such prominent figures as Gloria Steinem among her fans). But Wonder Woman was also a complex fantasy object for her creator, a projection of and vehicle for the transmission of his erotic and political desires — two categories that were equally inextricably linked in many of the publications he produced throughout his academic and journalistic careers. I’ve written about Marston’s intellectual and emotional investment in Diana at considerable length elsewhere, so I won’t belabor the point here; but suffice it to say that at times Marston seems to have imagined (perhaps only half-seriously, but nevertheless with all the creative energy at his command) that he could change the world through his Wonder Woman comics. Working through her, he believed he could contribute to the reformation of the basic structure of sexuality itself, at least as manifest in 1940s American society.

As Shakespeare’s John of Gaunt hopefully opined from his own deathbed: “He that no more must say is listened more/ Than they whom youth and ease have taught to glose.” Marston surely felt a similar hope when he sat down at his typewriter to enter Diana’s world for the last time; for in Wonder Woman #28 his idiosyncratic liberationist project resurfaces with a fresh urgency and insistence. The resulting three-part tale — “Villainy Incorporated,” “Trap of the Crimson Flame,” and “In the Hands of the Merciless” — is therefore more than just an affectionate backward looking glance at some of the weird and wonderful antagonists from Wonder Woman’s past (though it is clearly that, too). It is also a restatement of many of Marston’s key themes, as they had been sounded throughout his entire tenure on the title. More poignantly, it is his last attempt to lay out a set of principles that he seems to have honestly believed might mitigate some perennial aspects of human suffering.

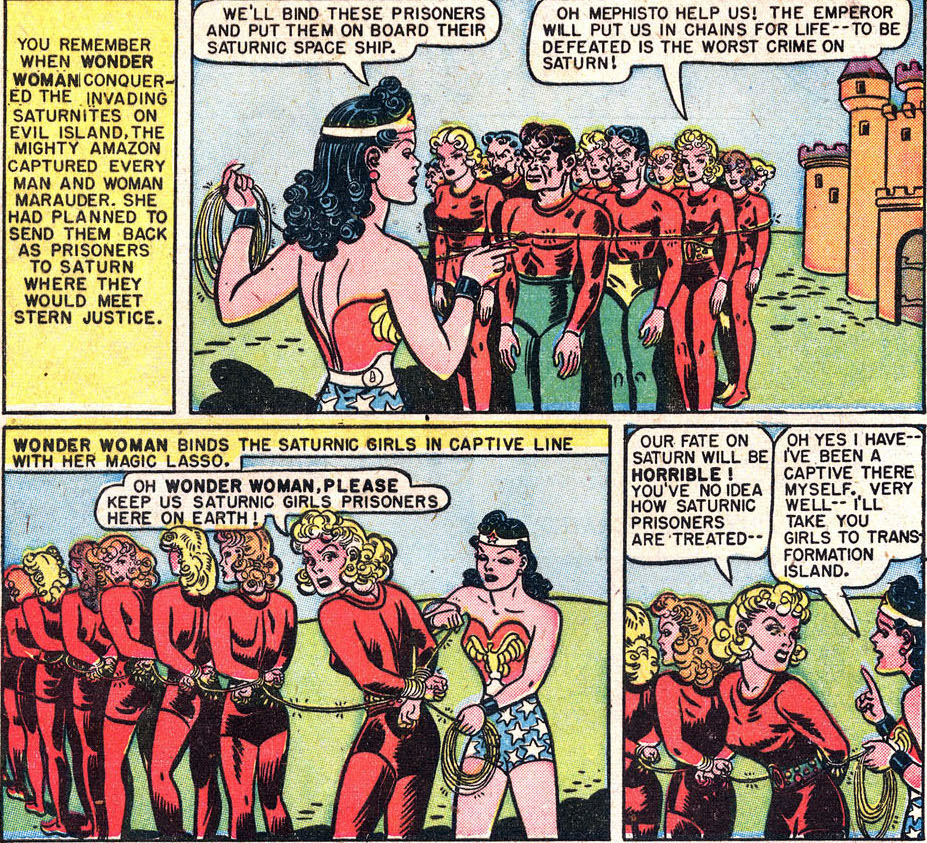

The story begins in media res, reminding readers of Wonder Woman’s recent defeat of an invasion from Saturn. The first illustrated panel (the second on the page, the first being taken up entirely with text) shows Diana having captured a large group of Saturnites in her golden lasso — which seemingly could expand or contract in length as needed, and here must be a few hundred yards long. Interestingly, artist H. G. Peter initially depicts a mixed group of Saturnite invaders, of both male and female genders.

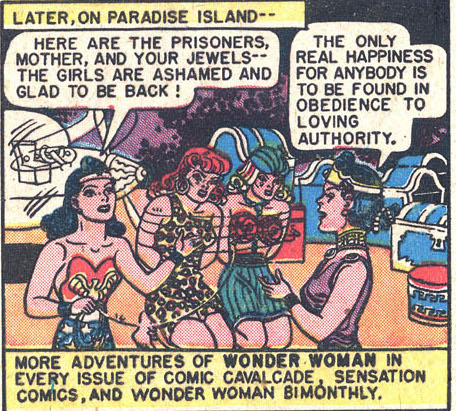

But in what I would regard as a telling slip, by just the second illustrated panel, the men in this group have mysteriously vanished; Diana (and Marston) is apparently only interested in the disposition of the female captive Saturnites, while the fate of the males is simply passed over. Attractively coiffed, and garbed in skintight costumes of bright scarlet, these “evil” young women are bound together in single file with their hands behind their backs, and transported by Diana in her invisible plane to the ominously named “Transformation Island” — the Amazon correctional facility. There, we are told, all prisoners are required to wear Venus girdles, a garment made from a “magic metal” that “compels complete obedience to loving authority.” This last phrase is spoken by the chief Amazonian prison officer in the final panel of the first page of the story; but it is repeated almost verbatim in the final panel of the very last page, by Diana’s mother Hippolyta: “The only real happiness for anybody,” we are assured there, “is to be found in obedience to loving authority.”

“Obedience to a loving authority.” Even for a reader unfamiliar with Marston’s psychological theories about the “primary emotions” of dominance and submission, the bookend status of this recurrent phrase signals the thematic significance of such concepts for the story at hand. And, indeed, the adventures that take place in between this repeated assertion depict several dizzying and occasionally hilarious oscillations between expressions of the impulse towards dominant assertion, on the one hand, and expressions of longing for a life of service, on the other. Thus, over the course of the first few pages, Eviless, a villainous (if rather unimaginatively named) Saturnite, turns the tables on her Amazon captors by forcing them to wear the Venus Girdles they have imposed on their prisoners, and thereby inverting the hierarchical structure of dominance and submission that characterizes the healthy “norm” of Transformation Island. However, while briefly wearing a Venus Girdle herself, even Eviless is momentarily tempted to surrender to the joy of captivity: “Now to remove this girdle … But I want to wear it — I feel so peaceful and happy!” As if to confirm the validity of those swiftly denied feelings with regard to the pleasure of obedience, several of the prisoners that Eviless subsequently attempts to release proclaim that they do not actually wish to be liberated at all. (“No, No! We don’t want our girdles removed!”). Eviless dismisses their desire to remain captive, of course — “You’ve let these Amazons break your spirit,” she declares — but later in the story, when some of these same happy prisoners have their girdles removed anyway, against their will-to-submit, we discover that a more profound change has actually taken place. “Without the girdle I feel dominant — invincible!” a girl named Irene discovers, “But I don’t feel cruel and wicked as I used to — the Amazons have transformed me! I love Wonder Woman and Queen Hippolyte … I must save them!”

At this moment, the regime of Transformation Island would seem to have produced the paradoxical ideal female of Marston’s psychological theories. Irene is “dominant” rather than submissive, but ruled by “love” rather than selfish “appetites.” (Marston’s preferred word in his academic writings for selfish-dominants is “appetitive”; he contrasts the appetitive type with unselfish-dominants, who he thinks can save the world by taking up the role of “Love Leaders.” Seriously. Read the last five or six pages of The Emotions of Normal People if you don’t believe me.)

In other words, the newly liberated Irene is just like Wonder Woman herself. She is an ideal personality type (in Marston’s preferred psychological terms), with a strong will to dominate that is nevertheless somehow conjoined with an equally strong will to love and serve others. We are encouraged to draw this parallel between Irene’s “new” post-Venus-girdle personality and that of Wonder Woman’s when she subsequently (and suddenly) develops Wonder-Woman-like powers: breaking free of her bonds, bending the bars of her cage, and freeing the other “good” prisoners. Irene goes on to lead a second rebellion of submissive-dominant prisoners against the prior rebellion led by Eviless and her dominant-dominant prisoners (the redundancy seems necessary if we are to keep track of who gets to “top” whom in this curious world of dominant and submissive flip-floppers). Irene then frees Wonder Woman (who had also been captured by Eviless), and together they restore order to Transformation Island; by which I mean that aggressively dominant types such as Eviless are once again placed in Venus Girdles, which cause them to happily accept roles of submission and service, while their mistresses (now including the formerly submissive prisoners who had earlier refused liberation at Eviless’s hands) once again dominate over them — lovingly, of course.

The inversions and reversal of the categories of top and bottom that produce this strange and paradoxical notion of order — in which loving-submissives-who-have-learned-to-dominate rule over recalcitrant dominant personalities that have been magically converted into submissives — are head-spinning. But they are also an inevitable consequence of Marston’s attempt to fuse his psychological theories, which assume the fundamental importance of the oppositions of dominance and submission in all human relations, with a liberationist-feminist philosophy of loving kindness.

This fusion should render certain arguments about Marston’s comics moot. For example, Trina Robbins has stated, on this website and elsewhere, that it is male readers (or “boys” as she sometimes calls them) that like to worry the issue of bondage in these comics, while female readers prefer to focus on the message of empowerment. Robbins is a creator and comics historian whose work I respect, but I’m strongly disinclined to accept this dubious gendering of our interpretive responses. (In fact, I can only wonder what Robbins would say to a woman who is interested in the depiction of bondage in these comics; would she accuse her of having more in common with “the boys” than with a woman such as herself, on the basis of such an interest?) But even if I were willing to reduce individual interpretive responses according to such gendered and heterosexist lights, the specific example of Wonder Woman #28 finally suggests to me that the very concepts that Robbins wants to separate — bondage and empowerment — actually cannot be disentangled in Marston’s imagination. As strange as many of Marston’s ideas undoubtedly seem, surely one of the single most frequently reiterated messages of his Wonder Woman stories is that there is no necessary contradiction between taking pleasure in bondage games (which, after all, form part of the regular recreational life of Paradise Island) and a commitment to female empowerment. On the contrary, for Marston, submission — of a very particular kind — turns out to be the best route to liberation. He said as much, prominently, twice, in this last story, so we wouldn’t miss it: “The only real happiness for anybody is to be found in obedience to loving authority.” The bondage sequences of his comics only make sense in the context of that curious philosophy.

Sharon Marcus describes the resultant imagery as “maternalist bondage.” This is a superb locution, in part because it acknowledges the fetishistic dimension of Marston’s scenarios while at the same time providing a strong indication as to the degree to which those scenarios depart from the typically polarized power structures of “traditional” BDSM, as superficially understood. (And yes, it is I think part of Marston’s achievement that a serious discussion of his work will lead one to posit a kind of BDSM that is “traditional,” simply in order to understand what the hell he is doing that is different.) But at the same time, and as Marcus has also clearly recognized, the phrase “maternalist bondage” also suggests some of the limits or problems inherent in Marston’s vision. At bottom (so to speak) the idea of submitting to your loving Mom is probably more disturbing or even icky than it is sexy for most of us. Of course, the reasons why that may be so are the basic stuff of psychoanalysis, and (as Marcus’s hints in her brief expositions of Jessica Benjamin’s work) these questions may even bring us closer to some of the (repressed) origins of the erotic charge present in what I am again forced (with delighted irony) to call more “normal” bondage. In other words, what we have here might have considerable potential as a psychoanalytic allegory — even if it probably isn’t going to bring about Marston’s larger project, which, as I’ve already said, was nothing less than the attainment of world peace through the reformation of sexuality. If we understand Marston’s logic, then, we can perhaps avoid getting caught up in a few older arguments about the politics of bondage — and even generate some newer and more productive ones.

_______________

The index to the entire roundtable on Wonder Woman #28 is here.

I was assuming that the men just got shipped back to Saturn and only the women go to transformation island…but you’re right that they don’t even both to make the clear. Marston/Peter — just not that interested in men….

I keep seeing a more straightforward, “non-kinky” message expressed symbolically through these B&D scenarios.

As with Wonder Woman regularly getting tied/chained up, then breaking free of her bonds, shows how the spirit and strength of Woman will eventually overcome all attempts to suppress her…

…likewise there’s a “non-kinky” message in Marston’s attitudes and prescriptions, so lucidly delineated in Ben’s preceding article.

Let’s bear in mind that Marston came from a far less cynical era. (Nowadays, all Catholic priests are considered pedophiles, all politicians are utter crooks, all cops are violent, corrupt racist homophobes, all reporters are either puppets of the Ruling Class or insidious propagandists for the Far Left…) A time when various authority figures, the Law, parents, our government, etc., were considered basically benevolent, well-meaning entities; with flaws exceptions rather than the rule.

Isn’t being a law-abiding citizen in a just society “submitting to a loving authority”?

A well-behaved child, attentive student, athlete who “plays by the rules” are likewise submitting — that is, following orders, restricting their behaviors to acceptable parameters planned for our protection (kids, don’t stick your fingers in light-sockets), intended to result in the Greater Good for the Greater Number — to a benevolently loving authority?

Whether we don’t shoplift, try not to run red lights, don’t sexually harass coworkers, we “submit” to external rules. And gain for it in greater safety, not needing to be on “red alert” all the time, having a clear conscience. With the satisfaction of knowing we’re doing the right thing, being considerate of others, helping make this world a more civilized place.

“A well-behaved child, attentive student, athlete who “plays by the rules” are likewise submitting ”

That’s true…but I think (to paraphrase Ben’s book) that Marston’s WW tends to make those kinds of submission look kinky, rather than those kinds of submission making his kind look un.

I don’t think there’s any getting around the eroticism of Marston’s WW. He wrote a soft-core novel, after all, with many of the same themes. I think he definitely sees the kinds of satisfaction you’re talking about as in part sexual — and all the better for that.

Thanks for your comment, Mike. To elaborate on Noah’s response: part of the difficulty, I think, is that Marston was an extraordinary sexual optimist who believed in the liberatory potential of desire. Although it is Freud who is usually associated with the logic of repression (“your neurozis iz a funktion of your represt longink for your muzzer!”), he was in fact far less optimistic about idea that facing and overcoming repressions might lead to “health” than Marston. There’s a dark side, an almost chthonic element, to Freudian libido. Marston, on the other hand, seems much more cheery; “free yourself from your repressions, give in to your (real) desire to be dominated, and you will be happy.” It’s really a kind of sex-faith – to the point that the possibility of acknowledging a sexual element in all the non-sexual scenarios you suggest (child-parent, student-teacher, good citizen before the law) would not be seen by Marston as a distortion or corruption of those scenarios. Marston would probably say that the very need to insist that those scenes are non-sexual is itself a sign of our tendency to view sexual energy (falsely) as inevitably corrupting.

Of course, that’s exactly how a puritan culture DOES see sex – as dangerous, forbidden, shameful, corrupt, and having NO PLACE in any of the social interactions you have described. In some ways, it’s that puritanism that Marston is responding to – but he really doesn’t think he’s being subversive by insisting that sexual energy does play a role in all those interactions, because sexual energy is an unqualified good, in his vision.

I don’t actually agree with that, and would be hard put to point to one place in his writings where he flat out says it – it’s more an implication of the larger theories. But I think it’s a fair characterization of his thought, and it helps to explain why his comics seem weirdly sexy and sexless at the same time (to our perhaps jaded, puritan-in-reverse, pornotopic culture). His vision is sex is simply too sunny for us. To that extent, the observation that Marston was less cynical than us is probably right on – although I wouldn’t attribute a lack of cynicism to his culture at large, for all that the standards for sexual display were very different from our own.

And of course there are tons of typos in what I just wrote but the second from last sentence should say “his vision OF sex”.

That’s a great comment, Ben. I would say in particular that the sexualization of mother/child love is really central to Marston’s vision — central as in erotic mother/child bonds are in some sense the prototype for how he thinks society ought to be organized.

A couple quibbles maybe: I think Marston does believe he’s being subversive; he pretty explicitly wants to transform society through a kind of erotic awakening to the joys of submission (and the attendant superiority of women.)

I also think that Marston is alert to the potential evils of sexuality. He thinks sexuality can be corrupted at least, by appetitive male drives. He’s way, way more willing to take a strong stand against sexual abuse than Freud was, for instance.

I liked Ben’s comment I made it into a post. Also a propos since it’s Marston’s birthday!

—————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

“A well-behaved child, attentive student, athlete who “plays by the rules” are likewise submitting ”

That’s true…but I think (to paraphrase Ben’s book) that Marston’s WW tends to make those kinds of submission look kinky, rather than those kinds of submission making his kind look un.

I don’t think there’s any getting around the eroticism of Marston’s WW. He wrote a soft-core novel, after all, with many of the same themes. I think he definitely sees the kinds of satisfaction you’re talking about as in part sexual — and all the better for that.

————————-

“Yes” to all that. (Ben wrote a book?)

It’s kind of an amusing reversal; where kinkiness may be hidden ‘neath innocent-looking scenarios (“There are pictures within pictures for boys who know how to look,” as Wertham put it), in Marston’s WW beneath the kink, there are perfectly respectable, even societally-acclaimed meanings.

Right after my last post, realized I’d forgotten to add the ultimate “obedience to loving authority”: religion, with God as the figure one submits to, the better to find , as believers (and Wonder Woman’s mom) put it, “the only real happiness.” Why, “Islam” even means “voluntary submission to the will of God”.

And “happy birthday,” William Moulton Marston, wherever you are!

Ben’s excellent book is here.

Thank you! Ah, I remember hearing about that one…

To follow up on the “more straightforward, ‘non-kinky’ message expressed symbolically through these B&D scenarios” in Marston/Peter’s Wonder Woman I’d mentioned earlier:

———————–

Isn’t being a law-abiding citizen in a just society “submitting to a loving authority”?

A well-behaved child, attentive student, athlete who “plays by the rules” are likewise submitting — that is, following orders, restricting their behaviors to acceptable parameters planned for our protection (kids, don’t stick your fingers in light-sockets), intended to result in the Greater Good for the Greater Number — to a benevolently loving authority?

————————-

The “reversals” that occur with dizzying speed in the WW story spotlit by Ben in his article likewise echo those which occur on our lives. From being childrem being cared for by our parents, we end up as their caretakers, anxious they don’t hurt themselves, careful they don’t get taken advantage of by conmen and scammers.

If we see and report (or even do a “citizen’s arrest”) a reckless driver or other lawbreaker, aren’t we not simply submitting to the authority of the law, but acting as its enforcers?

If we go from voter to elected official, addict to anti-drug activist, worshipper to minister, tantrum-throwing child to adult who now understands why their parents acting as they did, reformed criminal who now tries to keep kids “on the straight and narrow,” we are likewise enacting the role-reversals illustrated with such amusing luridness in that WW story…

As for being the “owner” of a cat: who is the “top” and “bottom” in that relationship?

(By the way, what a delight of swirling motion and figures is that last “Inspired by Irene’s example” panel in the Wonder Woman page above. Bravo, Harry Peter!)

I’m glad I found this entry last. All I can say is, I agree with everyone’s analysis. :-) And I’m gonna get Ben’s book.