Bronx Kill

Writer: Peter Milligan

Artist: James Romberger

I learned two things from reading Bronx Kill.

1) In my previous post on crime comics, my definition of the genre was too narrow. Most crime comics tend to be about hard-boiled detectives, vigilantes, or dangerous heists. In other words, they’re typical male adventure stories. But there is another type of crime story: the missing loved one. Like hard-boiled detective stories, the plot is based around a mystery – what happened to my missing wife/lover/child/etc. – but the mystery is much more personal for the protagonist, and the emotional impact of the crime is far greater. Missing loved one stories can sometimes function as vengeance fantasies, which could be seen as empowering. But more often than not they’re much bleaker stories where death and loss are inescapable, pain is all-consuming, and discovering the truth is actually far worse than not knowing. The most famous example of this sub-genre is The Vanishing, in which a man obsessively searches for his missing wife for three years, only to discover her terrible fate by sharing it.

Bronx Kill faithfully sticks to the missing loved one formula. The plot follows a novelist named Martin Keane, who wakes up one morning to discover that his wife is gone. Her disappearance has a strange connection to the murder of Martin’s grandfather and a rundown section of the Bronx riverfront named, obviously, the Bronx Kill. As the weeks go by, Martin’s sanity begins to slip, and he becomes increasingly irrational and violent until he finally stumbles upon the awful truth. And as these stories tend to go, the truth is far worse than the mystery.

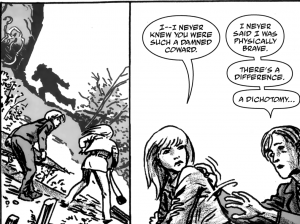

Judged solely on its merits as a missing person mystery, the Bronx Kill is a decent comic. Milligan never strays far from genre conventions, but he knows how to pace a story and arrange the pieces of a plot so that the outcome isn’t obvious from page 1. Romberger’s art is functional and unassuming; it doesn’t add much to the comic but at least it doesn’t distract from the story either.

The one tedious aspect of the mystery is Milligan’s attempt to connect the main plot to a crime novel that Martin Keane is writing. The comic will occasionally be interrupted by a few pages of text about a murder in 19th century Ireland. Unfortunately, the novel is boring, and Milligan’s prose is often a chore to read. Rather than function as a thematic reflection of the main plot, the prose sections simply screw up the pacing.

2) The other thing I learned from reading Bronx Kill is that writers are not manly. I’ll repeat for emphasis: WRITERS ARE NOT MANLY. Apparently, this is the great tragedy of being a writer. You can create entire worlds and populate them with fascinating characters who enrich people’s lives, but at the end of day you’re still an impotent wimp. Worse, you’re a wimp who has to be saved by your girlfriend after being threatened by a bum.

And then there are the daddy issues. God help the writer who has a father with a manly profession, like law enforcement. 50% of Bronx Kill is just Martin dealing with the fact that he can never live up to the expectations of his old man, a respected New York police detective. And while I’m trying to avoid being spoilerish, I can’t resist noting that Martin is cuckolded in an exceptionally emasculating manner.

To be fair, Milligan seems to know just how ridiculous it is for writers to constantly fret over their masculinity. Martin Keane may not be as tough as his father, but he eventually realizes that his dad is full of shit. And Martin is at least competent enough to solve the mystery of his missing wife (albeit only after a big clue falls conveniently into his lap).

But acknowledging the shortcomings of the masculine ideal isn’t the same thing as coming up with an alternative. And Milligan is still working within the confines of a male genre, so the climax of Bronx Kill is the same as the climax of most crime stories: fists, guns, and screaming. Nor are the wife’s motives of any real importance. This is yet another story that’s all about men dealing with their crappy fathers.

Bronx Kill is an uneven, occasionally engaging entry into an often overlooked sub-genre of crime, though a reader’s enjoyment of the comic is dependent on their tolerance for writers with daddy issues.

The art looks interesting; sketchier than you usually see in mainstream titles….or maybe I’m just appreciating the fact that it’s in black and white…

I think all of Vertigo Crime is in black-and-white, which is a smart move on Vertigo’s part, given the genre.

But while Romberger has an appealing style, he never really does much with the B&W format. There are scattered noir touches here and there, but I preferred Victor Santos’ work in “Filth Rich” (the only other Vertigo Crime book that I’ve read so far).

I really like Romberger’s style for this book. I think he does alot with the layout and the tones to push the mood. It’s totally right for the story.

With all due respect, it is difficult for a reviewer to know if an artist has contributed content to a script, unless one has seen the actual script in question. Without itemizing any of my specific amendments or additions, I should say Peter Milligan is well attuned to the comics medium and thus he allows the artist a certain amount of latitude to interpret his script, similarly to how a film scenarist would leave it to the director of a movie to visualize the depicted events. But then, the reviewer may just have meant that my art didn’t add to his enjoyment of the story, so fine.

As to the “manliness” issue, I appreciated that Peter did not write a crime comic full of “cool” scenes of manly men posing with their guns and the other pathetic glamorizations of violence that permeate the genre.

BTW, the header for his review on TCJ should have read The Bronx Kill by Milligan and Romberger, as we are co-authors of the book in question.

The header for the review is my doing; my apologies.

I’m pretty sure Richard was just saying he wasn’t that into your art. I didn’t see him making any statement about your contribution to the plotting or storytelling one way or the other.

You don’t seem to have necessarily understood his criticism of the book’s gender politics….but so it goes.

Well, “add.”

Yeah, no, that other wasn’t meant to address his interpretation of the content.

My statement in the the review probably required some clarification. I didn’t mean to imply that Milligan was the sole storyteller in the comic. What I meant was that I didn’t find the artistic style to be exciting or engaging. Or to borrow James’s phrasing, it didn’t add anything to my enjoyment of the story.

Now I’m off to work…

Fair enough. For criticism, I myself prefer a thoughtful hip assessment by Frank Santoro or a knowledgable nod by Paul Gravett, but there you go.