A perhaps unlikely, but nevertheless useful starting point for discussing cartooning is classical art—not seen as its polar opposite, but rather as its elevated obverse, similarly aspiring toward truth.

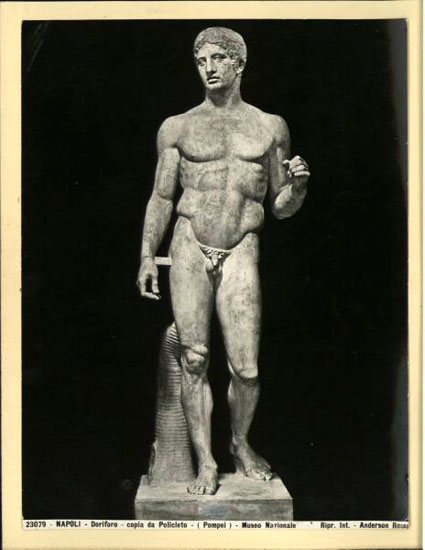

Polykleitos’ famous Doryphoros, or spear-bearer (c. 450-440 BC), as it survives in a Roman copy, is a good example. Acutely aware of the particulars of human anatomy, the sculptor distilled from empirical study a now-lost canon of perfect proportion, which applied mathematical principles to the creation of beautiful form. Neither the body, nor the face of the statue appear to us as an unadorned depiction of a man, but nevertheless convinces us of its truthfulness to nature through the sculptor’s evident, careful attention to the human form. It works as a rational prototype unto which we can easily map ourselves.

We learn from Pliny that the Greek painter Zeuxis (late 5th century BC) had similar concerns. Famously having to paint Helen of Troy, he took from five individual models their most beautiful traits and combined them to render that historic beauty. His painting, then, was an abstraction from nature used to project a recognizable prototype. An approach that has as much to do with Aristotelian cognition as it does with Platonic idea.

In his groundbreaking Essai du physiognomonie of 1845, the cartoonist Rodolphe Töpffer describes cartooning as a way of portraying the soul of the individual through the condensation of traits into archetype. He further noted that it does not require systematic study of nature, but rather works through a system of almost sign-like notation, immediately identifiable to us.

Sound familiar? To be sure, there are important differences between classic and cartoon form, and the latter has indeed been regarded as an irrational mockery of the former through the modern age, but their fundamental endeavor seems to me strikingly similar. One deals with rational prototype, while the other focuses on profane archetype; one necessitates a detailed understanding of nature’s principles, while the other requires a good eye for human physiognomy and behavior.

Essentially, however, they are both idealist endeavors, distilling experience into visual forms, and thus appealing to what is described by neuroscience as our understanding of phenomena through prototypes synthesized in our brain, into which new experiences are integrated and thereby processed.

Essentially, however, they are both idealist endeavors, distilling experience into visual forms, and thus appealing to what is described by neuroscience as our understanding of phenomena through prototypes synthesized in our brain, into which new experiences are integrated and thereby processed.

Töpffer was writing at a time when the cartoon was more pervasive in society than it had ever been, but as a way of drawing it is as old as representational mark-making. In the renaissance, the kind of notational, linear, and exaggerated drawing today associated with it, appears in marginalia, on the backs of canvases, and in other places one would expect to find doodles.

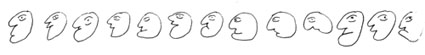

A compelling example is the suite of heads on the back of Titian’s so-called Gozzi Altarpiece in Ancona (c. 1520). Surely drawn by the master, and probably his assistants, when the huge panel was still in the workshop, they run the gamut from naturalistic to grotesque, and in places approximate minimalist abstraction. And several of them, most notably the female profile on the right, recall classical form.

The most famous doodler of the age was, of course, Leonardo, who throughout his life would populate the margins of his manuscripts with a variety of grotesque heads. An outgrowth of investigations into human morphology and the spectrum of human emotions not unlike Töpffer’s, they embody his notion that an artist would invariably express his self, resorting to its subconscious typology if his attention veered from manifest nature.

It is surely no coincidence that Leonardo’s two most repeated heads, the grotesque so-called ‘old warrior’ and the beautiful young ephebe, invoke classical models—the former is adapted from portraits of the Roman Emperor Galba, while the latter clearly reflects the Hellenistic ideal of beauty. As with Titian, it seems a natural impulse on the part of the artist, reminding us of the strategies of simplification integral to classical art, and of the fact that all art, from the exalted to the grotesque, seeks a synthesis of idea and form in its search for truth.

Hey Matthias. It’s good to have you on HU!

I wonder…is the purpose of art always, or even generally truth? It seems like artists might have other primary goals — entertainment, making a living, bashing one’s enemies, amusing oneself — a slew of possibilities really. Is cartooning by nature idealist? I’m willing to accept that that’s what some cartoonists are doing — but it seems maybe a stretch in other cases….

Hi Noah, thanks! It’s good to be here!

And yes, absolutely — not all artists strive for capital-T Truth; I use the term in a more basic sense, in that art will almost invariably to strive for some kind of mimesis, whether internal or external.

A cartoonist, for example, generally wants to get things ‘right’, to have his drawing resonate with the experience of the beholder.

I’m sure there are borderline cases — I think your recent discussion of Zen art for example provided an interesting challenge to this very Western notion, but as I believe you pointed out, the drawing in question still engages some concept of truth.

Okay, I didn’t quite get that you were arguing specifically for the point being mimesis.

I would say that, based on this one book about zen art I’ve been reading (rather than on, you know, actual expertise or knowledge of any kind) I think you’re right to say that eastern art (or certain kinds of eastern art) are much less interested in this. Can I find a quote quickly…?

Yes!

“Paul Cezanne, on the subject of landscape painting, said that the Old Masters “replaced reality with imagination… They created pictures; we are attempting a piece of nature.” The painters with whom we are concerned would have been baffled by Cezanne’s stated goal, for their object was never a documentary or architectonic study of nature but a representation of an inner essence, or an embodiment of the artist’s feeling about or interpretation of nature and of man’s relationship to nature.”

So if there’s a truth there it’s a subjective one, at least in some sense — less about mimesis to nature than about representing one’s own perceptions….

Abstract art would maybe question this as well. Obviously, there’s some abstract art which is obsessed with truth and getting closer to nature (ab-ex certainly is, I think.) But…I know my own drawings can be more about formal divagations; starting with something that looks more representational and seeing just how badly I can mangle it through my technical limitations. I’m not sure that that can be exactly seen as a quest for mimesis — which seems fairly directed and goal oriented. More like a farting around….which I guess raises the question of whether doodling, or at least certain kinds of doodling, might not be an end in themselves rather than an effort to achieve mimesis per se….

This touches upon a complex set of issues that I hope to have touched, if not adressed in detail in my piece.

First, what Cézanne recognizes in classical art is, I believe, more complex than what that quote might suggest. He is emphatically mimetic in the sense that he wants to convey a sensory experience of nature, but at the same time he is obsessed with the kind of essential form fundamental to classical art.

As for the Zen artists, as I understand it, they are dealing with an inner truth, or a philospohical one, but a truth nonetheless. I believe this is what Leonardo is getting at in his own way, when he writes that every artist will invariably express his own self. While patently invested in the observation of nature, he recognizes that any experience will be subjective, so yes, the truth that the Greeks for example regarded in objective terms has elided towards a subjective one in the modern era.

Leonardo, similarly, describes what you say about doodling, precisely because it is done without a specific purpose. He recognizes that he returns to similar forms when he’s doodling and sees that as expressive of his inner self, anticipating modern notions of the subconscious, but beyond that basically intuiting that nothing we create will be entirely chaotic.

Abstract art is similar in this regard — it’s a major challenge to the concept of mimesis, but an abstract artists will still work according to something he or she finds works. You might argue then, that by this point, my concept of ‘truth’ is stretched beyond any kind of usefulness, but I think it’s still valid.

Anyway, my specific point was more local, proposing that cartooning taps into the same basic principles that are fundamental to classical art, and that a compelling tension between the two arose when artists revived and reformulated the purpose of art in the renaissance.

I guess I do think that equating what “works” with mimesis seems maybe dubious…. Though it certainly makes sense to see cartooning as linked to classical Western art. Though…isn’t it equally influenced by Eastern forms, at least since the 19th century? I guess I”m curious; do you think da Vinci is more important, or more of an (indirect) influence on current cartoonists than is someone like Hokusai?

Sorry for the confusion, I was trying to characterise ‘truth’, not ‘mimesis’, although my use of the latter was also stretched a bit beyond its traditional meaning, to encompass something internally recognizable.

As for influences, I don’t know. Non-Western art, including Eastern is obviously important. The thing about Leonardo and cartooning is not so much his direct influence on modern cartoonists, but rather the fact that he intuited and was perhaps the first to formulate the concerns with which most of them deal. So it’s more a question of an important family relationship than of influence.

is that a gang starr allusion in the title?

It is.

Indeed :)

For those interested, I wrote a rather lengthy obituary over on my blog.

Guru RIP.

Pingback: Review fumettologica -3 « Fumettologicamente

uhm… the links to the Royal Collection Trust don’t work. I get redirected to the front page.

:<

oh I’m an idiot. didn’t see the date, haha. sorry!