This first appeared in the Chicago Reader.

_____________________

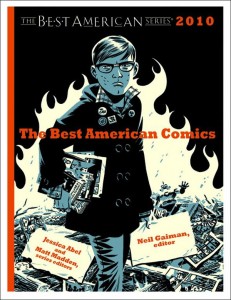

Neil Gaiman, who edited the 2010 installment of The Best American Comics, occupies a prominent but strange place in the history of the form. His Sandman series (1989-1996) was hugely popular and critically acclaimed. Although set in the traditional DC Comics universe—with walk-on parts for everyone from Hellblazer’s John Constantine and members of the Justice Society to obscure villains like Dr. Destiny—the book was original in tone and appeal. In place of steroidal underwear fetishists done up in primary colors Sandman offered pale, thin Dream, who wore somber contemporary or period garb and angsted rather than fought his way through unhurried, character-driven fantasy narratives, strewing portentous bons mots in his wake.

Neil Gaiman, who edited the 2010 installment of The Best American Comics, occupies a prominent but strange place in the history of the form. His Sandman series (1989-1996) was hugely popular and critically acclaimed. Although set in the traditional DC Comics universe—with walk-on parts for everyone from Hellblazer’s John Constantine and members of the Justice Society to obscure villains like Dr. Destiny—the book was original in tone and appeal. In place of steroidal underwear fetishists done up in primary colors Sandman offered pale, thin Dream, who wore somber contemporary or period garb and angsted rather than fought his way through unhurried, character-driven fantasy narratives, strewing portentous bons mots in his wake.

In short, Sandman was goth.

Superhero comics mostly appeal to guys who’ve been reading them since they were 12. Goth, as any Sisters of Mercy fan will tell you, often appeals to girls. Sandman offered enough pulp adventure to keep many young male readers—myself included—interested. But it reached beyond that fan base. As Best American Comics series editors Jessica Abel and Matt Madden note in their 2010 foreword, Sandman “single-handedly upped the ratio of women reading comics.”

Trouble is, Sandman only increased the number of female readers as long as those readers were reading Sandman. The book didn’t change the demographics of the industry as a whole. Though highly respected and popular, the series had remarkably little influence.

Certainly there were loads of Sandman spin-offs. DC has, following Gaiman, shown some interest in fantasy-oriented series—the currently ongoing Fables for example—and independent titles like Gloomcookie and Courtney Crumrin followed a goth-oriented, female-friendly path. But these efforts were marginal. Overall, post-1990s, the mainstream comics industry first drifted and then scampered towards massive, complicated stories mostly of interest to a male, continuity-porn-obsessed fanbase. Gaiman moved on to writing novels (notably, sophisticated fantasies like Neverwhere and Coraline), and the formula he created was largely ignored. Instead of creating goth comics for girls, American companies chose to stick with insular cluelessness and let the Japanese have the female audience. Manga comics, especially those aimed at girls, exploded in popularity here. And that, in case you were wondering, is no doubt why the Twilight comic adaptation isn’t drawn by homegrown artists like Jill Thompson or P. Craig Russell or Ted Naifeh but by Korean illustrator Young Kim, in a manga style.

Gaiman’s influence is weak even when it comes to Best American Comics 2010. One of the oddest things about the book is how little it has to do with its editor’s oeuvre.

I mean, yes, it’s possible to make connections between Sandman and some of the selections here. An excerpt from the lyrical The Lagoon, by Chicagoan Lilli Carré, plays on goth tropes and the meta-contemplation of storytelling in a Gaimanesque way. The dreamlike pacing, melodramatic romance, and kissing skeletons in Lauren Weinstein’s “I Heard Some Distance Music” might also be seen as at least elliptically referring to him. And the heavy-handed cleverness of a passage from David Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp—a billboard advertising firmamint for diarrhea, for instance—points to one of the less appealing aspects of Sandman. A more positive echo can be found in the first selection in the book: an excerpt from Omega the Unknown by Jonathan Lethem, Farel Dalrymple, and Gary Panter that fuses superhero goofiness with literary smarts.

The American mangaesque style, arguably descended from Gaiman, is represented in a few places, such as an excerpt from Bryan Lee O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim vs. the Universe. Still, there’s nothing in this anthology that you can look at and say, “This wouldn’t exist without Neil Gaiman.”

That’s OK though. Sandman had some serious problems, one of the most prominent being the inconsistent, generic, and even shoddy work of some of its pencilers. The visuals throughout this volume are much more distinctive and engaging. Theo Ellsworth’s “Norman Eight’s Left Arm,” from Sleeper Car, sets crude figures against detailed natural backgrounds to create a look that’s half clip art, half woodcut—a lovely complement to his surreal tale of woodland creatures, weeping gnomes, and gambling robots. John Pham channels Chris Ware to create an elaborate, fractured board-game-like layout for his tale of despair and neurosis among spindly, cosmically marooned characters in a Sublife excerpt called “Deep Space.” Comics canon standbys like R. Crumb and Ware himself are represented with visually pleasing selections. And sometimes when the art isn’t so great—as in Dave Lapp’s charmlessly clunky “Fly Trap” or Michael Cho’s bland, text-cluttered panels for “Trinity”—there’s at least a consistent visual style.

Even when he makes awful choices, you’ve got to admire Gaiman’s eclectic enthusiasm for a comics world that has so little to do with him. I cordially loathe Derf’s nostalgic hagiography of punk rock. Peter Kuper’s indifferently rendered anti-Bush commentary is as vacuous as it is predictable. And one earnest account of a national disaster per book is fine—either Katrina or 9/11, please, but both makes it look like you’re straining. Still, I found it pleasantly disorienting to see all of the above clumped together under a single editorial imprimatur.

Of course, not-something-you’d-expect-Neil-Gaiman-to-like doesn’t really constitute editorial vision. Gaiman actually cops to the lack of coherence in his introduction, saying that what he likes most about comics is that it’s “a democracy, the most level of playing fields.” Foolish inconsistency is the point—a celebration of “the biggest secret in comics: that anyone can do them.” And yet there remains a curious lacuna in Gaiman’s collection. Critic Stephanie Folse (aka Telophase) picked up on it immediately. After reading the collection she e-mailed me to say that it ironically “reinforced that . . . I don’t much like slice-of-life stories, autobiographical fiction, surreality, or political ranting in prose or comics. . . . Escapism all the way for me!”

Personally, I like surrealism, and can make my peace with slice-of-life, autobiography, and political ranting in at least some contexts. But I get Folse’s complaint. There are lots of different kinds of comics represented in this book, but intelligent, imaginative, escapist Gaiman-esque pulp for all genders isn’t here.

Maybe it’s the nature of the project. The Best American Comics series aims for a literary bookstore audience. Still, if you’re going to invite Neil Gaiman to be your editor, it seems like you might sneak in a few pieces for his fans, however scarce that kind of work is these days. Gaiman’s Dream wasn’t perfect, but he did have a dark, melancholy charm. It’s sad to see him abandoned so utterly that even his creator seems barely to remember him.

Yes, anyone can do comics, but few can master them. The book perhaps reflects that Gaiman doesn’t truly understand the art of graphic storytelling. It is as if he views comics as a stepping stone to other, more profitable forms of expression. I doubt that he is aware why the best comics bearing his name are those done by highly-skilled cartoonist P. Craig Russell, who adapts Gaiman’s text entirely to the comics medium and adds his own sense of timing and poetic visual orchestration to the pages. Left to his own devices, Gaiman’s work is verbose to the extreme. His better artists such as Charles Vess, Dave McKean, Jill Thompson or Chris Bachelo can add extremely sophisticated visuals to the work, but they are exceptions rather than the rule; one gets the sense that to Gaiman, artists are expendable and interchangable. He rarely discusses their contributions with much acuity or depth. He is the star of his own show, so his most lasting legacy is Vertigo’s writer-centric crediting system, writers in large type on the covers, artists as appendages.

Ouch.

I’m no Gaiman apologist. Sandman never did it for me, and if I’ve read anything else by the man (which is likely) I’ve forgotten it. That said, he’s on record as tailoring his scripts to his artists, and he’s said that he wrote the Sandman issues referred to above to the pencillers’ strengths. Whether he succeeds is another story.

And is it really fair to blame Gaiman for Vertigo’s marketing strategies?

I guess I agree that James is being harsher than I would…. I think I might put it more as that Gaiman seems to struggle some with the visual sensibility of comics, rather than that he’s willfully indifferent to it. He gave P. Craig Russell a lot of leeway with that issue, and I’m sure he’d acknowledge that the finished product owes a huge amount to Russell’s talents. At the same time…I think linking the inconsistency of Gaiman’s best american comics project to the fact that he doesn’t have a well-developed visual aesthetic or a strong personal investment in comics as comics is probably pretty dead on.

I assume you mean the Ramadan thing, but no, Gaiman wrote that as a script I think. I wasn’t so enthralled with that….I was talking about Murder Mysteries, Coraline and The Dream Hunters, 3 different books that Russell adapted to the comics form from Gaiman’s prose. Those are the better comics done from Gaiman stories IMO.

James, the writer-centric publishing approach is gross, but come on, you’re not being at all fair to Gaiman’s bibliography. If you dismiss Gaiman’s collaborations with Russell, Vess, Thompson, Bachalo and (!!) McKean as “exceptions”, you’re not left with much “rule” left. He chose a nice group of artists for that Sandman reunion, too.

I’ll conceed that it is Vertigo who have long had the tendency to put out comics with pages by one artist cut through with jarringly random pages by another, that it is Vertigo who decided to make the writers’ interests supercede that of the artists, beginning the negative credit trend that has infected the entire industry. Perhaps I am overmuch blaming Gaiman and those of his fellow writers who allow this type of thing to happen—maybe they don’t have a say in a policy that gives them the advantage. I do like the Russell adaptations much more than Gaiman’s other work, but I also admire a few of the other collaborations, particularly the Shakespeare revisioning with Vess and and the inventive Mr. Punch with McKean. And I suppose I could be holding it against him that when I met the guy he was dismissively rude.

Are the “Best American Comics” chosen the same way as the other “Best Americans”? The other entrants in the series work on a model where the über-editor(s) choose 100 semi-finalists and then the guest editor chooses the final ones. This might explain why the Best American Comics collections often appear to be virtually identical, regardless of who edits them while, say, the “Best American Essays” is very different each time.

(BTW: A good explanation of this whole process is contained in David Foster Wallace’s brilliant introduction essay for his year editing The Best American Essays. It’s actually a bad collection, his reasoning for what he chose is interesting but the focus is TOO narrow and not diverse enough; the collection itself is like a dozen essays about the intelligence failures that built the case for the War in Iraq plus a piece by Malcolm Gladwell. Sometimes, I suppose, editorial focus can be a bad thing.)

It does seem that the “Best of” series feels interchangable with the Anthologies of Graphic Fiction and that hardcover McSweeneys collection in that many of the same cartoonists are in all of them, and have been lumped together to form a sort of “new establishment” of comics. I begin to feel bad for some of the individual victims who do not deserve to be made part of any army but who because of this generalization appear ripe to be overthrown, as all establishments deserve to be.

Eddie Campbell on the prominence of Neil Gaiman’s credit on the Sandman jackets, from TCJ #273:

In the latest editions of the Sandman books, I noticed Neil Gaiman’s name up along the top there, as Neil Gaiman’s Sandman. It’s taken some getting there, but it finally got the author’s name on the top of the book. And any artist who’s ever worked on that, I think, he or she knew full well they were doing so as Neil’s guest. Neil is the author of those books. Doesn’t mean he’s the only person working on them, any more than David Bowie’s the only person working on one of David Bowie’s albums.

Gaiman wrote “Ramadan” as a short story for Russell to adapt. He wanted to see Russell give it the treatment given to other works such as the various operas and Oscar Wilde’s fairy tales.

I haven’t read a Sandman episode in about fifteen years, so I can’t say how well they hold up. (I looked at Mr. Punch again in conjunction with the poll last year, and I gave up on it after about 20 pages.) Regardless, the Sandman material is one of the few things in comics one can show people outside the subculture and have a reasonable expectation that they might hook into it. Gaiman may not be a good storyteller per certain factions of the comics subculture, but his stuff has an appeal to the culture beyond that. He’s one of the handful of comics creators this can be said of, and I think it’s nothing to sniff at.

It’s definitely competent non-superhero genre fare in an idiom that appeals to women as well as men. It’s somewhat depressing that that should be an achievement for American comics at this point…but there it is.

I respect Eddie’s work but he and I don’t agree on everything. Every artist who draws a comic is a co-author of the comic in question…but I’m not going to argue further about it with RSM, who seems to have forgotten that he requested that I don’t respond to his comments

James–

1) If we can keep things civil, I have no problem with you responding directly to anything I write.

2) As for the substance of Eddie’s statement, I actually agree with you for the most part. I do think Gaiman’s collaborators are the co-authors of the individual stories they work on with him. However, I also believe that Gaiman should be considered the author of the Sandman series overall. Eddie made a music analogy, so I’ll make one, too. “My Little Town” is a Simon and Garfunkel record, but the album it appears on, Still Crazy After All These Years, is a Paul Simon solo album, and rightly so. He’s responsible for the direction of that album in the same way that Gaiman was responsible for the direction of the Sandman series. The collaborations don’t change that.

Fine.

Eddie does most of his work on his own, and so is, I think, self-effacing and somewhat less invested in his collaborative mode…he can afford to be generous with credit.

I suppose you are making a case that Gaiman is like the late Harvey Pekar, another writer whose work I admit that I am not very fond of, who also worked with a lot of different artists, did not have much of a visual sensibility (IMO) and dominated the credit on his collaborations. I guess I can see your point. The bottom line for me is that I am not usually interested in the comics done by either of these writers, it seems to me that much of their work could just as easily have done in another medium…it is no surprise that they both gravitated in more recent years to film.