There are times I read something on the internet and feel this immediate need to respond. I think we’ve all felt that way about topics we care about. Thus is created the comments thread, the message board, and other forms of abbreviated, often argumentative discussions. For me, I don’t always feel capable of forming my thoughts and reactions into a coherent text, especially in a way that avoids being combative (I really don’t want to be that way). So I save links and texts in hopes of later returning to them and making some grand statement, some coherent argument, some well thought out response. But waiting for that time to come is often counter-productive as sometimes making the incoherent statement and getting feedback is where the real discussion and learning comes from.

Writing about the idea of comics and poetry has been on my to-do list for quite awhile. I’ve a note in Evernote from December of 2008 labelled “Comics as Poetry.” The note is just a bunch of collected links to people like Tom Hart, Bill Randall, and Gary Sullivan, all dating from early in 2008. I also have one paragraph of a started post from April 2011, and a never completed review of Warren Craghead’s How to Be Everywhere from February of 2011.

I feel strongly that there is a line of comics poetry that runs through the history of comics, but I always end up getting stuck on how to delimit such a feeling. What is comics poetry? What is poetry? Similar to asking “what are comics” or “what is literature” this is rarely the most productive place to start… and thus, the not starting.

What started me up again this time were two recent articles on the topic: Steven Surdiacourt’s “Graphic Poetry: An (im)possible form?” at Comics Forum and an interview with Bianca Stone at The Comics Journal from this past week. Both immediately set off my desire to respond.

First off, Surdiacourt’s article starts with the term “graphic poetry” which I find unfortunate. I can see the desire to parallel the “graphic novel,” (which he explicitly uses in one definition: “graphic poetry is to the graphic novel, what poetry is to prose”), but I don’t think it is a good idea to work from an already contentious misnomer of a term. Also, “graphic poetry” sounds like something a person in the 1950s would have used to describe “Howl.” Don’t let the children read that graphic poem.

Surdiacourt’s text itself starts off on good footing, discussing the inspiration for the article: an exhibit that featured paired up collaborations between comics artists and poets. He immediately notes the tendency to have the artists illustrating poems, rather than the two truly collaborating. We’ve seen this before with the work published by the Poetry Foundation (here’s the last one in the series with links at the bottom to the others) under the rubric of “The Poem as Comic Strip” (that title alone tells you something). What we find there is a bunch of comic artists (some, like Ron Regé Jr., whose regular work is often comics poetry) illustrating poems by famous poets. It’s quite reminiscent of that bastion of comics greatness Classics Illustrated and not particularly inspiring (see Bill Randall’s column about the series). Of course, this model works for people in the poetry world because it maintains the integrity and primacy of the original poem/words.

Back to the essay at hand, it draws heavily on an article by Brian McHale about narrativity and segmentivity (I’ve only managed to read sections of it via Google Books which seems to cleverly only skip the pages where the primary analysis is done). McHale starts with poetry but turns to comics, spending the majority of the article discussing Martin Rowson’s adaption of Eliot’s The Wasteland as way to compare the two forms’ use of segmentivity and narrativity. Surdiacourt summarizes McHale’s theory:

…this segmentivity is defined as “the ability to make meaning by selecting, deploying, and combining segments” (Rachel Blau DuPlessis quoted in McHale 2010, 28). It’s not merely their gapped nature that connects poetic texts and graphic narratives, but also their shared capacity to play off “segments of one kind or scale […] against segments of another kind or different in scale” (McHale 2010, 28). The best known example of this kind of poetic configuration is obviously the enjambement, a trope in which the grammatical unit of the sentence (measure) is disrupted by the unit of the verse (countermeasure). A similar textual device is used in comics to create or maintain tension by the interruption of the action (measure) at the end of the end of the right hand page (countermeasure). [DB: Those are his ellipses and references.]

Surdiacourt rightly notes that this single criterion is not enough to compare comics and poetry. So, he also (briefly) brings up poetic rhyme in comparison with visual rhyme, braiding, as well as Barthes’ hermeneutic code. All of these can be gappy aspects of comics. In McHale’s article he also briefly discusses film, comparing filmic cuts to poetic segmentivity and the gaps in comics, noting the tendency of classical Hollywood style films to make cuts/gaps as invisible as possible (though one can argue against that when there is a desire to provoke mystery or suspense) in contrast to an Eisensteinian montage where gaps are introduced to force viewers to “make meaning.” I think the latter use of gaps is one place where comics can foreground their constitutive elements (images in sequence) in a similar way that much poetry foregrounds words and sounds.

Unfortunately Surdiacourt focuses on textual segmentivity, and his only example (from Nicolas Mahler) is primarily about the text. He ends on a strange note: “In the end, what and how graphic poetry can be (if it can be at all) remains to be imagined, and drawn of course.” He seems completely unaware of the existence of work that would fit his category, that would even better fit his category than his or McHale’s examples.

Certainly, looking at any comic by Warren Craghead provides a great example of segmentivity, a gappy aesthetic, and usage of various tactics Surdiacourt mentions. Craghead almost never uses text in the traditional way it is used in comics (balloons, captions), instead he fragments sentences and words into pieces (the word, the letter, respectively) and scatters them across the page. His pages and panels are also visually segmented as he tends to use images that are singular or partial–a single object, part of a larger object or scene–and then connect them visually through composition, lines, and text.

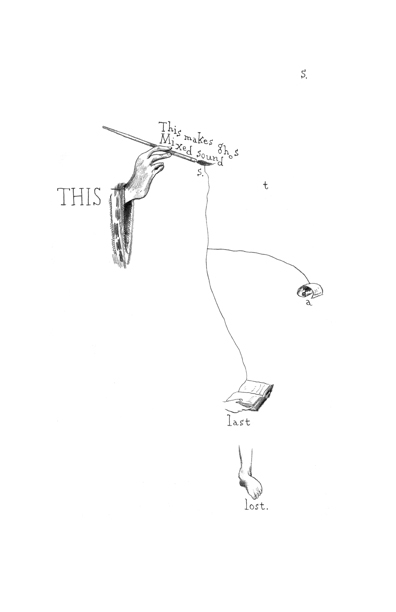

For instance, this page from “This is a Ghost” shows a fragmentation of sentences, words, and imagery. The fragmentation creates a rhythm to the reading as one moves across the page through the multiple sizes and spacing of the text. You can note that the (admittedly out of context) sequence of images is not a “smooth” transition. Also, when read in full (see the references list below for a link to a pdf of the anthology), one finds a use of repetition (both word and image), braiding, and visual rhyme across the comic’s 14 pages. The comic tends to force a different type of reading than a conventional narrative comic that provides a very smooth and transparent reading. Craghead’s comic engenders a closer reading and a tendency to reread nonlinearly as one moves back and forth through the pages trying to decipher its layers (in a sense this echoes the hermeneutic code).

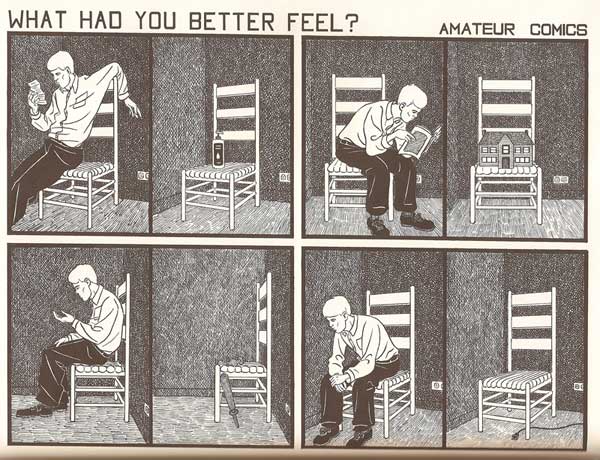

Much of John Hankiewicz’s work would also fit well as an example for Surdiacourt. For example, his “Amateur Comics” sequence makes use of segmentivity in an unusual way that could mirror McHale’s measure and countermeasure. Each page from the sequence is divided into four groupings of two panels. The groupings’ two panels are divided only by a single line, while the groups are divided by the negative space of the gutter. In most of the pages, the groupings divide up into a panel with a person in the left and one without a person on the right. The left and right also often show different views of the same scene, sharing view across all four groups. In this way, Hankiewicz disrupts one narrative sequence with another, creating a network of potential sequential and spatial readings of the 8 panels on the page. The spatial organization in conjunction with visual content, which at a general level shows alternating imagery, makes use of repetition and creates rhythm within the page and across the sequence of pages. Similarly the two lexias of text across the top of each image (a question beginning with a series of interrogative abverbs and a two word phrase in the form of “[something] Comics”) also form a consistent set of repetitions and variations that can be read across the pages. Without even discussing the specific content of the images, it’s fairly easy to see how one can read “Amateur Comics” as a form of comics poetry.

So, that’s just two artists off the top of my head, and neither are that obscure in the comics world. Both comics provide examples that are considerable more invested in the interaction of text and image in a “poetic” (let’s put my usage of this term aside for now) way than just the text by itself.

I wish that before he decided to posit something that he didn’t think existed, Surdiacourt would have looked for examples of that supposedly nonexistent thing. I’m sure if he looked around a bit he could have found some examples. Certainly, Rob Clough wrote about Hankiewicz’s work as “comics-as-poetry” in The Comics Journal (the online version is easily searchable), and there are often (mostly brief) examples to be found fairly easily.

Bianca Stone, who explicitly calls her work “poetry comics” and edits a poetry comic column at The The, was interviewed in The Comics Journal and shows a similar lack of knowledge of artists working in the comics world. Stone’s foregrounding of “poetry” in her terminology does point to her grounding in the poetry world rather than the comics world, so that could be part of the reason (none of the comics she explicitly mentions are outside the mainstream (be it superheroes or “alternative”)). The interview bears this out as she discusses being in an MFA poetry program and not having much interaction with the comics world. (There are a bunch out us out here, Bianca.)

Even her definition of poetry comics points to a focus on text as poetry: “Sequential art that uses poetry as the text.” I realize she is surely simplifying here to have a quick definition, but the concept makes it seem like the work is “poetry + comics” a kind of addition wherein the comics–the images and the iconography and grammar of comics–is an add-on to the poetry, which is text. Some of the work she’s put in her column has born out this conception. To her credit, Stone’s work in her I Want to Open the Mouth God Gave You Beautiful Mutant doesn’t totally play out that formula, though I think it does come through stronger as a poem via the text.

For this reason, I use the term “comics poetry” as a way to foreground the comics aspect, a more succinct locution than Clough’s “comics-as-poetry”. Comics poetry isn’t poetry as text with comics images; it’s the whole comic as poetry. The images, the words, the structure, the rhythm, the page, all of it is used together to create the poetry, to create comics in a poetic register. But, as I mentioned in the beginning, this gets tricky, since “poetry” and “poetic” can mean a lot of things to different people.

In the end that doesn’t really help us identify or discuss how comics poetry differs from any other comics. So, I’ll take that up in part two (later next month), looking at how a few other people have discussed comics poetry or the poetic in comics, and then I’ll offer my own thoughts on the matter with some more specific examples.

References:

- Craghead, Warren. “This is a Ghost.” In Ghost Comics, edited by Ed Choy Moorman. Bare Bones Press, 2009. 151-164. Order the volume or read the pdf: http://edsdeadbody.com/barebones.html

- Dueben, Alex. “A Bianca Stone interview.” The Comics Journal. 24 Aug 2012. http://www.tcj.com/a-bianca-stone-interview/

- Hankiewicz, John. “Amateur Comics.” In Asthma. Sparkplug, 2006.

- McHale, Brian. “Narrativity and Segmentivity, or, Poetry in the Gutter.” In Intermediality and Storytelling edited by Marina Grishakova and Marie-Laure Ryan. De Gruyter, 2010. 27-48.

- Randall, Bill. “Deaf Ears: Poetry, Comics and the Poetry Foundation’s Comics Project.” The Comics Journal #288 (February 2008): 193-5.

- Stone, Bianca. I Want to Open the Mouth God Gave You Beautiful Mutant. Factory Hollow, 2012.

- Surdiacourt, Steven. “Image [&] Narrative #5: Graphic Poetry: An (im)possible form?” Comics Forum. 21 Jun 2012. http://comicsforum.org/2012/06/21/image-narrative-5-graphic-poetry-an-impossible-form-by-steven-surdiacourt/

A few more comic artists who might fit in this vein (for at least some of their work):

Julie Delporte, Oliver East, Franklin Einspruch, Allan Haverholm, Aidan Koch, Simon Moreton, Anders Nilsen, Jason Overby, John Porcellino, Alexander Rothman, Frank Santoro, Gary Sullivan, me, and surely others I am obviously forgetting.

Note: I added that list of artists at the end at the very last minute (after forgetting to do it earlier in the writing process). It’d be better if I had mentioned or linked to specific works. Alas.

I think that the relationship between the poem and the image working together collaboratively is so, so important, and one that I take very seriously in my work. I constantly have stressed that I believe that to merely illustrate what a poem is saying is not at all what I am interested in. I tried to define poetry comics in the simplest terms exactly out of respect for all the artists out there doing comic poetry/poetry comics/graphic poetry, etc. I emphasized that my definition was far from being the absolute. There are poetry comics for example (as Alexander Rothman really explored in his symposium talk the other night) that have no text at all. But it’s true, I’m a poet professionally and the poetry is an important part of it for me. As I said, I’ve been learning. I’m aware that there’s been a rich culture of comic poetry for years and years. I’m glad to be getting to know all this incredible work (Hankiewicz’s and Craghead’s are just stunning!). I hope that we can communicate and collaborate, and discuss with each other rather than accuse one another of not fitting into specific definitions. It’s a nebulous, evolving form, and a small world that explores it. I am grateful for it, and I think it puts us in an exciting position.

I think one question that sort of floats through this piece is whether using “poetry” to refer to comics is simply a metaphor, or whether it can have a more or closer formal connection. That is, is “poetry comics” analogous to “graphic novel”, or is it more like saying, “the painting was poetic.”

I guess I tend towards thinking the second…though I think you’re right that there are certain techniques of poetry that have analogs, or similar formal devices in comics. But that seems to be the case for *all* comics. Peanuts, for example, definitely uses the panels as a rhythmic device to pace the dialogue. But I don’t know that it quite makes sense to call Peanuts “poetry comics.”

At the same time…it seems like there should be *something* to call this group of artists and artwork, even if just to make them easier to talk and think about (and, not incidentally, to market). So maybe “poetry comics” works as well as anything….

Hi Bianca, thanks for responding. I did note the provisionality of your definition and that I didn’t think your work necessarily fit that formula. I wasn’t trying to call you out or anything on that account, it was just the confluence of your interview and Surdiacourt’s piece which got me back to this topic. Both made it clear that work that I and some artists I consider colleagues (like Warren) as well as other artists I don’t know (like Hankiewicz) are making work that clearly isn’t getting “out there” quite enough explicitly in this context. (Though I was glad to hear Alexander had so many examples to use in his presentation. I hope he can get the audio together so I can hear what he had to say.)

Kind of out of this context, I really did enjoy your collaboration with Anne Carson.

“Peanuts, for example, definitely uses the panels as a rhythmic device to pace the dialogue. But I don’t know that it quite makes sense to call Peanuts “poetry comics.””

Sure, similar to the way a lot of prose can use rhythm and sound but not be poetry. For me, I think it’s more about how some of those elements are foregrounded in place of other elements such as the narrative or the joke. Though you do have poetry like limericks which are combo of that formal structure and joke… Peanuts as limerick?

I always think of Peanuts more as koans than as limericks….

It fluctuates. Some are more jokey than others, imo.

Nice work, Derik. I have an essay on John H. that deals with a few of these issues:

http://www.tcj.com/construction-manual-john-hankiewicz%e2%80%99s-%e2%80%9cthe-kimball-house%e2%80%9d/

I came up with the admittedly-clunky term comics-as-poetry in 2006 (?), after I saw Hankiewicz at an SPX panel talk about “rhyming” panels visually. In my article, I specifically avoid the term Poetry Comics because it implies a poem with an illustration, which has been done many times and has nothing to do with comics-as-poetry. I actually think Comics Poetry works pretty nicely, come to think of it.

I’d add Tom Neely to your list, in part because there’s an elasticity to Comics Poetry that allows for a kind of narrative in much the same way that Poetry does. There’s a new cartoonist named Christopher Adams (he has a book debuting with 2D Cloud at SPX) whose work also fits into this category. Also Jason Overby and Blaise Larmee have done work that fits here. Some of Sophie Yanow’s recent autobio diary comics have been done in this manner.

Ken: Thanks. I’ve already got your article in Evernote under “comics poetry” for future reference.

For those not Ken, I highly recommend you read that article.

Rob: I’ll admit to not having read much of Neely’s work. I find his drawing style off-putting to my tastes.

I’ve not heard of 2D Cloud or Adams, so I’ll have to look that up. I did include Jason in my list there are the end. As for Blaise, a lot of his work seems much more in the vein of conceptual art than poetry. I agree on Yanow, some of those diary pages are really lovely and poetic.

Thanks for this article—it’s very exciting indeed to see this subject getting close attention lately! Here are a few thoughts, at the risk of being scattered:

The (somewhat idiosyncratic) definition of poetry I put forth in my talk was that poetry is a category of language that gets maximum work from its constituent parts. Every element of the word and its presentation is there for the poet to use—sound, in terms of things like rhythm, alliteration, and assonance; the relation of the words to each other in terms of spatial arrangement, inclusion in stanzas, and in terms of meaning through things like allusion; punctuation, enjambment, tone, the order in which sense data are presented… I could go on for a long time.

I say “category of language” rather than form because most of those things apply to any good writing, from novels to essays to postcards. I say “work” because well-written poetry has a tendency not just to present us with ideas, but to have us reenact them. I used the example that when a sensitive reader encounters Gerard Manley Hopkins, she doesn’t just read about an ecstatic experience, she recreates it.

That’s much more of a practitioner’s definition than a critic’s (which is just how I like it), and I fear that it doesn’t do much to help us differentiate cartoonist–poets from just plain cartoonists. But I’m not terribly concerned with that. Whether Peanuts is poetic comics or poetry comics, it gives those of us working in this field plenty to draw on.

I think that idea also fits in pretty nicely with what I understand of DuPlessis’ notion of segmentivity. I’m also fascinated how writing on this subject seems to keep coming back to her. Derik, I know you mentioned Tamryn Bennett’s thesis a while ago, but did you ever get a copy of it? Also, I just looked her up and saw she teaches at Temple. I’m wondering if you had any interaction with her there?

“To her credit, Stone’s work in her I Want to Open the Mouth God Gave You Beautiful Mutant doesn’t totally play out that formula, though I think it does come through stronger as a poem via the text.”

I strongly disagree on the second part of this point. I think much of the strongest work in this field uses its visual imagery almost like handwriting, so that the quality of the mark making is greatly tied up in the creation of voice and tone. Craghead, Koch, and Moreton provide great examples—and I think Stone does as well. The poems in I Want to Open The Mouth God Gave You… depend greatly on her striking visuals.

Alexander, I think that any formal definitions involving artistic genres are really problematic. I would say that “poetry is a category of language that gets maximum work from its constituent parts” except for all the times that it isn’t. Prose poems, for example, often don’t work like that. And, of course, lousy poems often don’t work like that.

I think it’s generally more useful to define poetry as “those things which are recognized as poetry.” Poetry (like comics) is a historical and social construction, which has formal elements (short, lineation) but uses those more as touchstones than as absolutes.

Which is why it becomes hard to pin down what poetry comics might be. Poetry isn’t really defined by its formal devices, so trying to see formal parallels with comics ends up being more about metaphor than form. But…again, if you can get enough people to use the term, it’ll take on its own momentum, which is probably a good thing for marketing purposes, so….

Alexander, thanks, I’m going to save that definition for my notes for part 2. I had totally forgotten about Bennett’s thesis (there wasn’t much info up last time I looked at her site), but I just emailed her and she’s sending me a copy. Also, I think you’re mistaken on the Temple thing.

As far as my comments on “I Want to Open…” I should have unpacked that more, but I ended up really wanting to keep my deadline and the top of the post grew faster than the bottom. For me Bianca’s work… it pulls through stronger via the text as I’m reading, if that makes sense. The text is creating the movement/rhythm/pacing more than the images? I’ll try to flesh that out at a later point too.

Noah: Part of this post that got cut (maybe for part 2) addressed: “In a certain sense we can take the sociological path and say ‘poetry is what the people and institutions involved with poetry say is poetry.'” Which I was borrowing from Bart Beaty’s defining of comics via the same type of locution in his Comics Versus Art (which as you know, what I was originally writing about). I think that type of definition can work on a broader level, but it’s not totally helpful in this type of discussion with sub-genres.

Pingback: Madinkbeard | Derik Badman » Comics Poetry, Poetry Comics, Graphic Poems

Noah, I certainly agree that the endeavor is problematic, but I reached my definition with things like prose poems in mind. Note I’m not saying that poetry uses *all* of its constituent parts—prose poems don’t use lineation etc., but I think what separates them from just another paragraph is that they’re drawing on some other “extra” elements of language. These elements don’t necessarily sonic qualities or visual arrangement—perhaps they involve a strong use of imagery, or the irony resulting from stringing together a bunch of non sequiturs—but they go beyond a completely straightforward transmission of information.

Tom Hart suggests that a “deft handling of compositional elements” is close to the heart of poetry, and I think that’s about right—but “deft” seems to imply intention, and therefore to exclude automatic writing, etc….

The danger with definition like mine, I think, is that it’s so broad that it could really describe any good writing. The danger with talking about “those things which are recognized as poetry” is that the discussion must look backwards to a degree, and that’s less useful for discussing an incipient form like comics poetry.

All of which is to say that I think there’s real value in categorizing this stuff formally, with full knowledge, of course, that it’s a slippery task.

The task of a functional comics poetry definition is a daunting one. I commend Derik for its undertaking. Even very well established genres of art are plagued by exceptions and asterisks, and the simile of herding cats comes to mind. It’s hard even to identify the purpose of any genre taxonomy, whether as a tool for grouping commodities for consumers, to outline criteria to criticize others, or to chart trends and fads from a historical context.

Derik’s point about segmentivity, which is a very large part of Tamryn Bennett’s aforementioned dissertation, is a strong position, that I think is significant.

I think Alex brings up a great idea in the “practitioner’s definition” and what qualifies as success in one’s own work.

I also like Noah’s point, “Poetry isn’t really defined by its formal devices, so trying to see formal parallels with comics ends up being more about metaphor than form.”

Well, one advantage of being skeptical of formal definitions, maybe, is that it pushes you towards thinking about cultural factors…which in this case might mean talking about influence rather than form per se. That is, one way to think about poetry comics might be to ask whether there’s a group of practitioners who are self-consciously influenced by both poetry and comics. Then it becomes less about form and more about people more or less intentionally situating themselves as a new genre or sub-genre.

And it works at least in part here, right? Warren and Bianca both seem like they’re influenced directly by poetry…however that does or doesn’t translate into formal terms. It also perhaps creates a situation in which illustrations of poems can be somewhat thought of as in the genre, or related to the genre, rather than trying to say that they don’t have anything to do with it, which seems like it isn’t quite the case.

I think that what Bianca and these other young poet-artists are trying to do is fiendishly difficult: a perfect integration of words and pictures … in fact, I think this is really the Holy Grail of comix, distilling the essence of words into pictures and vice versa.

The crystalline structure of verse forces the reader’s brain to shift out of the purely optical mode of looking … the situation is paradoxical and delicate … along with Matt Madden’s experiments with Oulipian comix, this business of poetry-comix may well prove to be the (Long) Promised Land of the North American comix scene.

Noah, I think that’s a good point. There’s something at work here that’s both intentional and yet undefined…so somehow incidental. For me, personally, I think it has something to do with pushing against the boundaries of what has already been established. So it’s not about immediately making a new set of rules, but going beyond the confines of our own genre, allowing those OTHER interests we have into our work. We so often feel we cannot stray from what we think is poetry, or what we think is a graphic novel–but to organically and naturally interact with our creativity is what produces new hybrid forms, ones that inform BOTH the poetry and the image. Ultimately the two working simultaneously to create a kind of third thing. Right? Of course I’m influenced directly by poetry, but that’s the direction I come at it from. Everyone comes at this new form from various positions, and the result is as varied as any artform is varied. I do want the movement/rhythm/pacing to come from the text, for the text to be strong in that way, which is perhaps what I experiment with. So I think Derik made a good point: the text is working similarly to how images often work in a traditional comic (?) that they themselves, being musical or whatever, propel and the reader forward as visuals do. Well, something along those lines…

Anyway. I think it’s the willingness to experiment creatively, to not know what you’re doing, and to be ok with that, that is important here.

I like that, mahendra! “The crystalline structure of verse forces the reader’s brain to shift out of the purely optical mode of looking … the situation is paradoxical and delicate …” beautifully put.

Am I being obtuse, or is there some reason why Dave Morice who has been publishing his magazine “Poetry Comics” for almost thirty-five years doesn’t get a name check in this article?

Various work by him here:

http://www.poetrycomicsonline.com/

Matthew: I was going to mention him, but I’m a nice guy. If I mentioned him I would have had to say how horrible I find his work. I was trying to be mostly positive, despite having criticisms in the article.

“…going beyond the confines of our own genre, allowing those OTHER interests we have into our work…” [Bianca]

I think in my own work that is the case more and more as I bring in… tactics from other art I like. Certainly a lot of my work from the past couple years has been influenced by the whole Conceptual/Uncreative Writing concept.

“…one way to think about poetry comics might be to ask whether there’s a group of practitioners who are self-consciously influenced by both poetry and comics. Then it becomes less about form and more about people more or less intentionally situating themselves as a new genre or sub-genre.”

Definitely sounds like a valid approach to me, and I don’t mean to suggest that I’m dogmatically against it.

“It also perhaps creates a situation in which illustrations of poems can be somewhat thought of as in the genre, or related to the genre, rather than trying to say that they don’t have anything to do with it, which seems like it isn’t quite the case.”

I’m not sure I understand this part. Are you referring to “The Poem as Comic Strip” series? I share Derik’s frustration with that project, since I feel like it mostly ornamented work that was already complete. You mentioned marketing earlier, and I do appreciate it in those terms: it certainly introduced the idea of comics poetry to a new and wider audience. (And I like some of the pieces, like Regé’s, but as Austin Kleon points out, the writeup accompanying that one ignores that Kenneth Patchen was basically a cartoonist himself! http://www.austinkleon.com/2007/07/11/rege-patchen/)

BTW, Derik—DuPlessis is definitely at Temple. Her website confirms it, as does Tamryn’s dissertation. (It’s in an appendix of interviews, including one with me… do me a favor and ignore my rambling there.) Might be cool to draw her further into this conversation, as her ideas seem to resonate with many of us.

Alexander: Sorry, I thought you meant Bennett, not DuPlessis.

Alexander, I didn’t much like that series all that much either, for all the reasons folks here are saying. But…just because it’s bad doesn’t mean it’s not part of the subgenre. Every genre has bad bits in it.

You (or other readers) might like this project.

Sort of tooting my own horn there, but what the hey, that’s what the internet is for.

Derik, thanks for writing about my work. And for the nice words from others, thanks.

I come to comics not from the direction of poetry but from fine art, specifically modern painting. I went to school in art departments that knew very little about comics (or poetry) but did teach me a lot about visual art. Some of those painting values – multi-valent readings, mystery, confusion, formal strength, the reall communication of experiance – are the same things that I value in poetry. I have an auto-didact’s weird gaps in poetry knowledge but I guess I also don’t know enough to stop.

When I’m making stuff I’ll usually draw a ton while also writing a ton and then pick out the best and match them up.

I try to do what both “regular” comics-makers and poets do – set up rhythms, rhymes, a pace that goes faster or slower. Where the poetry comes in I guess is that instead of it being in service of an at least sort of cinematic story it’s all to make some weird shifting experience. I try not to point to an experience but to make one.

So in my work, yes, Apollinaire (oh god is there some Apollinaire), Stevens, Whitman. But also and in a similar way Giotto, Stuart Davis and Braque.

Derik, I think you are very good at setting up an “art” (or “poetic”) experience in your recent work. I esp love “Badman’s Cave” which is probably the only conceptual/appropriation art I really really like. There’s something so nutty and real about it.

ugh, typos. Sorry.

By the by, my latest column on my blog is about comics-as-poetry and some things related (but not quite the same as) to them:

http://highlowcomics.blogspot.com/2012/08/comics-as-poetry-and-stylized-comics.html

Warren: “I come to comics not from the direction of poetry but from fine art, specifically modern painting. I went to school in art departments that knew very little about comics (or poetry) but did teach me a lot about visual art.”

There’s probably a lot of significance to the backgrounds we come from. I went to art school (printmaking), but I think I ended up getting a better literary education through all the reading I did than any significant background in art history or theory (my school was pretty weak on that).

Thank you for for responding to my text. I have formulated some thoughts on your response in the comments section of my initial post. (http://comicsforum.org/2012/06/21/image-narrative-5-graphic-poetry-an-impossible-form-by-steven-surdiacourt/)

And I’m of course looking forward to the second part of your reflection on comics and poetry.

Pingback: Comics Poetry, Poetry Comics, Graphic Poems » Madinkbeard | Derik Badman

One comicker whose stuff seems to me to have a strong poetic aspect is Jon McNaught (Pebble Island, Birchfield Close, Dockwood etc.)

Especially in Dockwood (larger format), his layouts seem very metrical in the way he weaves together the various elements and threads of the work (visible in these – sadly poor quality – scans I took for a review; http://tiny.cc/h9hc1w http://tiny.cc/59hc1w)

Hi Tom, as it happens I’m trying to get my hands on a copy of Dockwood, as I’m moderating a panel at SPX this year that McNaught will be on. (That’s not announced yet, but I’m assuming the panels aren’t top secret.)